Latest Contributions

Memories of Assam: 1940s-1960s

Category:

Tags:

Bill Charlier worked in Assam’s tea gardens for many years. He eventually retired to live in Spain. He passed away in 2012.

Editor's note: This is a slightly reformulated version of material that originally appeared at http://www.koi-hai.com/Default.aspx?id=570017.

A Journey into the Unknown

When the war ended in 1945, everybody was trying to find a job as most of us were going to be demobbed. Fortunately, through family connections, I heard of some jobs, which might be available. Whilst still in the RAF, I went to London to meet the Chairman of the Assam Company. He said that there was the possibility of a job in Tea in India. Other choices included openings in Africa and in America. I chose Tea.

He asked whether I could get immediate release from the Air force, but I preferred to wait a few months until my proper group number came up. He then told me that I would have to go before the Board of the Assam Company in London.

The Assam Company was situated in The City in Lawrence Putney Hill. The office was up two or three flights of stairs in a very old building. Inside, one could almost see the working methods of a hundred years previous ... tall stools, high desks, figures bent over their work. The only thing missing was the quill pens.

I was directed to sit on a hard bench outside the Boardroom door. In due course, the Secretary called me. It was a large narrow room with a long boardroom table. Sitting at the far end were four directors and the chairman. The directors were of great vintage and questioned me as to why I should want to go to Tea in Assam. Simple answer, I needed a job and it sounded suitable for me. I don't know what else I could have said because I knew nothing about growing tea - or about growing anything to be honest.

There were further shufflings and murmurings and I was sent out of the room to wait on my hard bench once more. Eventually the Secretary told me that they had accepted my application. He informed me that I should receive a three-year contract and my salary per month in the first year would be twenty-five pounds payable on my arrival in Assam. I was also to have a bungalow to live in and one or two servants. Another condition was that in the first five years, there was no question of the Board allowing an Assistant to marry.

They required me, for the next few weeks, to go to Marshals Tea Machinery Engineers in Gainsborough. This I did at my expense. Within weeks, I received my sailing instructions - from Liverpool, on a Ministry of Transport Passage to Calcutta. The ship belonged to the Brocklebank Line. This was paid by The Assam Company.

In Liverpool, I boarded the ship and found my cabin, which was more or less a packing case, strapped to the deck. It had two bunks, a wash-hand basin and about enough space to swing a cat. When I entered the cabin, I found my cabin-mate was already there. He was seated on the lower bunk, which he had already claimed. He grunted at me and that is about all he ever did. He spent the next five or six weeks devouring gin in great quantities. In fact, I never did see him have a meal. It turned out that he had been a prisoner of war with the Japanese and was returning to Calcutta and to Burma.

Eventually, we landed in South India at Vishakapatnam, north of Madras. We were told that the ship could not sail to Calcutta because of riots there. This was, of course, pre-independence. There was a great deal of unrest. We were told that we would have to travel the rest of the journey to Calcutta by train. A few days before we arrived in port, my cabin mate stopped drinking. He was, in fact, a decent chap.

The problem now was that I had no money left to buy a ticket as I was only to be paid on arrival in Assam, the princely sum in my contract of twenty-five pounds a month. Luckily, my cabin mate loaned me the fare and said that he would get it back from the Company Agents in Calcutta. We shared a coupe, and he paid for all my meals.

In Calcutta, I was met at Howrah Station by a babu from the Agents, Kilburn and Sons with a pedal rickshaw. On arriving at the office, I was taken to see the Number One. He informed me that I would be travelling to Assam in two days' time and that I should need to buy for myself, crockery, tin bath, bed linen, and a whole host of other things for my bungalow. I listened to him and at the end of his list, made the statement, ‘I have no money.' This rather confused him, ‘No money, Unbelievable!' He then told me that he would arrange a small loan (£25, then 325 Rupees), which would be deducted from my monthly salary, to cover these purchases.

I then went to Whiteways and Laidlaw, the General Store in Calcutta and managed to provide myself with three knives, forks, spoons and plates - the Tin bath was OUT!

I was staying at The Grand Hotel, which was still principally occupied by the Military. So I was to share a room with two other chaps. I had to provide for my journey to Assam, food for two days, the length of the journey. I could get a hamper from Firpos Restaurant on Chowringee. There were various prices and I bought the least expensive.

After two days in Calcutta, I started my journey to Assam, on a similar type of coupe, which I shared, once more, with an Army Captain. During the early part of my journey, I opened my hamper. It was filled with bananas. After a day of eating from my hamper, the Army Chap asked me if I was particularly keen on bananas. He had noticed that that seemed to be the only food I ate. I told him the story about my journey and money problems. After this, he invited me to join him in a curry in the restaurant car. This I did and enjoyed the curry and a few cold beers. He did this twice for me during the journey. There are still Good Samaritans!

The journey to Assam took one night and two full days. We had to change trains half way by crossing the Brahmaputra by ferry. There was no bridge, and the railways were of two different gauges. I arrived at Nazira Station at eight o'clock at night. There was a car to meet me, and I was taken to the Assam Company compound, to the General Manager's bungalow. This was a large compound consisting of workshops, club, polo ground, and about eight bungalows, including a hospital.

At the assigned bungalow there was no one, except the servants, because it was Monday and Club night. A meal was waiting for me, and being pretty tired I went to bed. Next morning I met the General Manager. We had a talk at breakfast and then he took me down to Headquarters Buildings to meet the Accountant.

In his office he first asked me how much money I had borrowed, which seemed to be the general practice of new arrivals. He made arrangements for me to pay off my already outstanding debts, plus another loan of One Hundred Rupees to live on for the present time. Repayment was to be made monthly from my twenty-five pounds. He then told me that he would show me the Company Compound. This meant we went directly to the Club, and started drinking brandy and soda at eleven o'clock in the morning. The Club was quite a large building with a general bar, gent's bar, dancehall and changing rooms.

I managed to get back to the General Manager's bungalow at midday. He arrived at about twelve-thirty. We sat down to have a chat. He told me I would be going that afternoon to Towkok Tea Estate in Sonari District, about fifty miles away. This Estate, in those days, bordered on the jungle of the Naga Hills.

After lunch we went out onto the veranda and , sure enough, at the gates of his compound was an old, lease-lend, Chevy truck, piled high with cane plucking baskets, a driver, and ‘handy-man' and two jugalies. I loaded up my tin box, mounted the cabin of the lorry, which was more or less open and started the journey. We had several stoppages for problems with the petrol. There was a lot of sucking and blowing through pipes but eventually we arrived, about four hours later, at Towkok.

The reality

My arrival in Assam was dramatic enough. Now come the real facts of life in Tea in the mid-1940s. The Japanese invasion threatened Assam. They advanced as far as Kohima in Nagaland, and Assam was almost in the front line. The younger Assistants were conscripted into the services. During that period, the Assistants who were too old for the services were required to supervise the Labour from the Tea Gardens who were conscripted to build the Dimapur to Burma Road. The majority of the Managers, therefore, were very senior, having done more than their thirty years, due to the war.

On my arrival to Tea, those who had been away were returning. There were some rather grumpy managers, overdue for retirement, and were not exactly enamoured with the new Assistants, most of whom had also been to war, but were treated as though they had just left school.

The regime was strict. All Assistants at Towkok had to assemble at the Manager's Office at six-thirty in the morning (but in winter it was delayed to eight o'clock). We stood and had to listen to the Labour complaints being handled by him. I'm sorry to say, some of them got a clip behind the ear.

I shared an Outgarden Bungalow with an Assistant who had joined just before the War, and returned after being a prisoner of war in Italy. He was slightly on the mad side. For instance, when the cook, one day provided us with a pretty shocking lunch, he suddenly got up from the table, went to his bedroom and got his Lea Enfield rifle, supplied by the Assam Valley Light Horse army unit, and opened fire on the cookhouse. The cook and the pani wallah were seen disappearing into the tea, not to appear near the bungalow again.

Shortly I moved to a very dilapidated chung chota bungalow and was almost in the Factory Compound. It had wooden floors that sloped one way or the other. It was fifty years old and looked it. It had been used to store fertilizers.

I was to be a Factory Assistant. Every morning, after Office, I had to follow the Manager through the Factory. He was negative about most things. I did, on one occasion answer back, over some oil drums which had been cleaned out with paraffin. He considered them still dirty. My reply "I can't get into the b--- things." With this, he marched me to the Office and sent me to the General Manager in Nazira Headquarters with a LETTER. By this time, I could not care less.

Nazira was the Assam Company Headquarters - a large site where the General Manager, Secretary, Engineer, Chief Medical Officer, Surveyor, and their staffs lived. Workshops, a hospital, and stores made quite an impressive centre from where the thirteen Assam Company Estates were administrated. No agents were involved except the Forwarding Agents Kilburn&\;Co., Fairlie Place, Calcutta, who arranged the purchase of stores for the factories and sent them by river steamer. The polo ground and Nazira Polo Club were also in the compound.

The General Manager was rather astounded at the letter. He told me not to worry and sent me back with a letter to the Manager. The contents of the letter were unknown to me, but that evening I heard the Manager's car arrive at my compound. He came up onto the veranda with a bottle of whisky (then rationed). I did it justice!

I did have subtle revenge. There was a small nine-hole golf course hacked out of the jungle. The Manager was a keen golfer and talked a lot about his game. He always mentioned his delight in seeing jungley (wild) fowl around number five green. Living was pretty tight on about 350 Rupees a month. I had inherited an old Damascus-barrelled shotgun. My only transport was a bicycle, so I went on several occasions with the shotgun hidden in my trousers and went to bag myself with a few good meals. After a little while, the Manager at the Office mentioned that there must be some disease in the wild fowl because they were far fewer in number!

On the more serious side, during manufacturing, the Factory Assistant was expected to be in the factory at all times, except for short breaks for meals. This sometimes meant a period of eighteen to twenty hours, not much time for sleep. This particular Manager used to frequently sneak about during night manufacturing hours to see if I was about. But I had a good crowd of staff, who usually gave me news of his arrival in the Factory.

Steam Prime Mover

On my arrival at Towkok Tea Estate in 1946, my first posting was as Factory Assistant. The only power to drive the factory was two large steam engines, made by Marshals. These were horizontal engines, side by side. The main engine was a side-valve rated at 90 bhp, probably only fifteen years old. The stand-by was probably a much earlier piston-valved horizontal. Two Lancashire boilers were there, one as a stand-by and rated at 100lbs pressure. Both were mostly fired by wood, though some grit coal was used.

The main drives from the engine were cotton ropes, six of them, about two and a half inches in diameter. Each year the men from the Ganges Rope Company, Calcutta came to splice and repair the ropes ...an era of long ago that has never been repeated.

The Head Fitter was an old man called Jeepa, who had been at Towkok a great number of years. These engines were his life!

The starting procedure was a great show, whether during the day or at night. First, he would give three long blasts on a ship's steam whistle on the roof of the engine room. We reckoned it could be heard over five miles away. In the engine room, Jeepa supervised two engine drivers with crowbars to turn the huge cast iron flywheel until the slide valves were open in the correct position. Then, with great ceremony, he began to turn the steam valve very slowly. The engine would come to life with a great hissing of steam. The revolutions would pick up. Then, when satisfied that the engine was running properly, he gave another long blast on the whistle. He then salaamed the engine and handed it over to the Engine Driver and jugali. The ceremony was completed.

He rarely failed to be there and nobody was to touch the engine or the whistle until he arrived. On the very few occasions he was not there through illness, the Engine Driver would start it without ceremony. Jeepa, on his return would seriously puja the engine to atone for his absence.

The Shikari Wallahs

During my days at Towkok in the late 1940's, on the outgarden Namtolla, which was right up against the Naga Hills and very dense jungle, there had been considerable trouble with wild elephants. They were coming into the rice paddies and also into the labourers' lines, causing quite a lot of disturbance. This was particular to the cold weather and the onset of the rice harvest. The labourers had been spending most nights beating empty kerosene tins and waving fire torches with very little success.

Tom Darby, who was acting manager, decided that we should go after these elephants and informed the forest department, who agreed. In Sonari District, the District Medical Officer for the Singlo Tea Company was Dr. Bill Muir. He was in possession of a twin-barrelled point five, black powder elephant gun. All I had was a 405 Winchester, and Tom Darby, a 303 rifle.

We went down to Namtolla at about nine o'clock at night. We had rigged up a jeep headlight on a board with wires to a battery. The battery was to be carried by our labour helpers. At about midnight, the first reports came in that the elephants had arrived in the paddy fields. So we proceeded, a total party of three with guns and four labourers. My rifle was being carried by one of them because I was responsible for the headlight on the board. The batteries were carried by two of the labourers.

We got off into the paddy and could hear a number of elephants pulling up the ripened rice, thrashing it on their sides and eating it. We crept slowly towards the elephants. When we got to what we thought was fairly close, Tom Darby shouted, ‘Put on the light.' This I did. At about a hundred yards away was a group of elephants. Tom Darby started firing off his rifle, with every other round being a tracer. Doc. Muir got down on one knee and must have fired both barrels, at the same time. All I saw was him being thrown backwards by the force of the gun, ending up on his back about three yards away. The shots had obviously gone wild.

By this time, the elephants had become very aggressive and were trumpeting and stamping their feet on the ground - like a mini earthquake. With this, the labourers took off, dropping the battery. So out went the light. We were left in the middle of the paddy land, in pitch darkness, with a herd of very-annoyed elephants.

We decided that running was not the best action, so we stood perfectly still. Though the elephants had got our scent, they could not locate exactly where we were. After five minutes, the elephants, with a lot of trumpeting and stamping, turned tail and made off towards the jungle.

At camp, after a hasty retreat, a few stiff whiskies were needed by three very shaken Shikari Wallahs.

Enjoying life

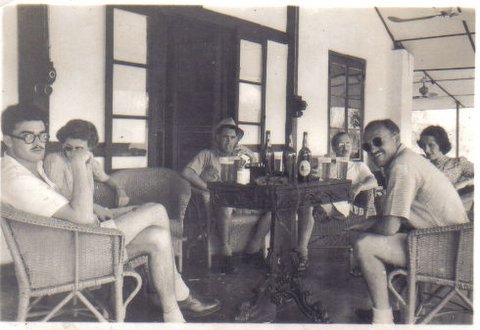

The photo shows a collection of erstwhile planters having a cold weather Sunday lunchtime session on the veranda of the old Sonari Club.

The photo shows a collection of erstwhile planters having a cold weather Sunday lunchtime session on the veranda of the old Sonari Club. In those days, there was an ample supply of imported Amstel beer.

From left to right, the photo shows Mac (?), Margaret Lobbin, Geordie Reed, Dr. Muir and Mrs. Muir. The vacant chair was mine.

The club was rather formal. Two very senior Memsahibs of Sonari, who had been in tea since the early twenties, sat on the veranda to receive felicitations from assistants of a junior status. There was however a problem. One was more senior than the other was by a mere few months. To pass your greetings, in error, to the junior one first was to incur the displeasure from the husband of the senior one later, in the Men's´ Bar, in such a way that everybody would know about it.

Treading very carefully was the order of the day. These were Burra Sahibs of thirty years or more, and they were men to be aware of by Junior Assistants.

During this period, in the cold weather, polo was played at the club twice a week, Mondays and Thursdays. There were some very good players - Ginger Morris, Brough, and Worman. We could muster three teams.

After three and a half years in Towkok, I was posted to Moran District.

1950s

Flying in Assam

In the early fifties, there were a few of us who had small planes of various descriptions. Some of them were ex-US Military. Williamsons had their own flight of two Austers and at one stage, had a Dragon Rapide, an eight seater. They had a professional pilot called Johnson who unfortunately crashed not far from Mohanbarrie Airport, killing himself and the mechanic. The Austers were flown by Stew Campbell and others, whose normal duties were Garden Assistants. Stew was an ex Fleet Air Arm pilot.

There was another unfortunate accident in Golaghat District where Mackenzie managed to fly into some trees on take-off from a garden strip, killing himself. He was in an Aeronca Super Chief.

For myself I had various aircraft, from Piper Cub (L4), Stinson Sentinel (L5), and an Aeronca Super Chief. The Assam Company helped me maintain these aircraft etc. and they were used on occasions by the General Manager and Visiting Directors, and sometimes by outside companies. This continued until 1964 when the Indian Government, in its wisdom, decided that foreigners flying about in Assam was not a good thing, due to the Chinese situation and the increase of Air Force activity. My license was suspended, which was probably a good thing because the company had decided that I had enough to do as the manager of Doomur Dulling estate. They had trained a young new Assistant in England to take over the Company flying. He did arrive and I tested him and personally would not have put him in charge of a bicycle.

The pictures below were taken in the cold weather, in 1952 at Gelakey on the small strip made from a garden road.

Me (Bill) with Birdie Richmond of Lakmijan, a very keen photographer.

The above picture was taken at a height of 16,000 ft. with no oxygen. We didn't stay long at that height!

There were another couple of notable figures in flying - Joss Reynolds of Panatola, and Peter Atkins of the North Bank. They both had light aircraft.

When my middle son George was a few months old, he developed a nasty go of Whooping Cough. My Chief Medical Officer, Tom Poole, suggested that I take him up in the plane to 10,000 ft. and fly for an hour. It was .a perfect cure. Within 24 hours, the cough was almost gone. The altitude allows the lungs to expel the mucous that causes the cough.

On occasions, I used to drop messages over bungalows, on little parachutes. Otherwise, without telephones it would days to communicate with neighbours.

It also came in handy at Christmas, to deliver Father Christmas to the club, to the great delight of all.

Planes in Assam in the Fifties

In the early fifties, on various wartime airstrips, there was a great deal of surplus American aircraft, from Piper Cubs to Dakotas. On one such strip, eighty miles outside Calcutta Balu Ghat, you could have bought a Dakota for as little as Rs 15,000. In fact, a lot of small airlines were started with these.

I managed to get my hands on a Piper Cub L4 in the Dooars for a pretty good price - around Rs 3,000. I had this plane when I was an assistant at Doomur Dulling and Gelakey. I used the Mackeypore wartime grass strip because there was no strip at Gelakey. The manager of Mackeypore, Cappie Davis, was instructed by the General Manager Tim Healy to construct a temporary bamboo hanger because the Company had shown some interest in the use of the aircraft to inspect estates.

Unfortunately, I had very little use of either. In a windstorm, the hanger collapsed on the plane. It was pretty badly damaged so I dismantled it and took it to Atkhel Factory Bungalow where I was living at the time. I mounted the engine on a couple of steel girders and ran it regularly, to everybody's consternation.

Not long after this a civilian Aeronca Super Chief was for sale in Upper Assam. It seemed to belong to a Marwari who had taken it in lieu of a debt! (The person concerned shall be nameless). Its condition was not very good. But as luck would have it, I had seen an advert in the Statesman that the Lucknow Flying Club were looking for Piper Cubs in any condition. I made contact with them and in a very short time a person arrived to see me. They were interested in making a deal.

It was agreed that I crate the Piper and send it by river steamer to Lucknow. In return, they would completely overhaul the Aeronca and give a free loan of a Stinson Sentinel L5. This was done and in about three weeks the Stinson arrived and the Aeronca went off to Lucknow.

The overhaul took about eight months, during which time I had the unrestricted use of their aircraft. It was a good plane, but expensive on petrol, having a 260hp engine, compared with 90hp in the Aeronca.

Eventually the Aeronca was ready and flown back to Tezpur, where we exchanged aircraft. They did a very good job of the overhaul. The plane was like new. I continued to fly it until the time of the Chinese problems. Then the Indian Government decided that private flying was not to continue in Assam. The Aeronca ended up being sold to a dealer in Calcutta Airport.

Aeronca after complete overhaul

Aeronca Super Chief, before overhaul, Gelakey strip

Piper cub taking off Thowra

Aircraft on loan from Lucknow Flying Club

Polo

The Nazira polo team, mid-1950s. These were the trophies won by these players: 1st Sibsager, 2and Sibsager, Roberts Cup, Junior Sibsager and Best Player

From Left to Right: Bill Dowsing, Tom Derby, Bill Charlier, Ian Leetham

Back row from left to right: Dr Tom Poole, Ian Leethham, Roger Wiener, Tony Yates, Page, Alistair Wright, Ray Corps, John Darby

Front row from left to right: Bill Charlier, Cappie Daivis, Tom Darby, Bill Dowsing.

The cups in the picture were all won in one year: best player, 2nd Sibsagar, 1st Sibsagar, Roberts cup, Junior cup played for by low handicap players.

1960s

Football 1964 Moran Planters.

Standing L to R: LC Hazarika (Referee), SK Bakshi (Dirai), Dewan Mehra, Chatrath, Nar Singh (Thowra), Chris Morris (Dekhari), Sohan Singh (Moran,) Hardev Singh (Dekhari,) SN Khonnikar (Teliojan)

Sitting L to R: Gilchrist (Bamunbarrie), Peter Clayton (Doomur Dulling), Julian Francis (Khowang), Bruno Banerjee (Captain) (Teliojan), Ray Town (Moran), Shekawat (Khowang)

Winnie the Leopard

In the very early 60's at Doomur Dulling Tea Estate, where I was manager, a busti wallah (local resident) arrived at the bungalow with a sack in which was a baby leopard, probably about a month old. I gave him a few rupees and took the cub. We called her Winnie.

In the past, when at Towkok, I had tried to bring up a tiger cub but it eventually died of malnutrition. This prompted me to write to the director of the London Zoo. I received an extensive reply explaining the importance that after the short period of weaning, all food should contain fur and feathers.

In other words, chickens and goats should still have the skin on them. This was important as it provided a proper digestion of the food and the well-being of the animal.

From the first day, we kept her free and only caged her at night for her own protection. She stayed with us for nearly fourteen months and was still free during the day.

During the period she was with us, my visitors to the bungalow became few and far between.

One incident comes to mind. The Assam Company Tea Taster and Manufacturing Advisor, Leslie Woolett, who made periodic visits to the factory, arrived and stayed to lunch, which was the custom. During lunch, Winnie bounded in from the compound on to the dining room table, straight to Leslie's lunch. With this, he fell out of his chair in horror, and disappeared under the table while Winnie made away with his lunch. It took a good deal of effort to get him out from under the table. He then made a very rapid departure in his car, without a word or backward glance. One bonus, I didn't have to worry about visits from that department for some time.

She was about the size of a young Labrador dog. Although she never threatened anybody, we were beginning to get nocturnal visits from the local male leopard population. In fact, one evening on the way to the club, in our driveway stood a full-grown black leopard. So at last came the sad time for her departure.

She travelled in a specially constructed crate. The design was given to me by the Colchester Zoo. We got her used to the cage by taking her out in it, on the back of the jeep. She was flown to Calcutta in a Dakota from Doomur Dulling Air Strip to meet the Pan Am Animal flight that came through each week. She was met in Calcutta by Pops, who ran the Sky Players, our private Dakota service of those days. He knew Winnie as he had stayed with me on occasions. I am told he actually walked her a little at Dum Dum near Hanger number 9. She had a collar and chain.

The area around the hanger became deserted very quickly. She arrived next day in Colchester in excellent condition. She produced two litters of cubs during her lifetime.

I did visit her on a couple of occasions. At the beginning, I could go into the cage with her, but later had to stay outside. She did still seem to remember me either by sight or by smell.

I am grateful to have had the experience of Winnie. It does show that it is possible to have a good relationship between a human being and a wild animal.

February 2005

This is the story of Bill and Lois Charlier's January 2005 visit to India.

Malaga - Frankfurt - and we were off to Delhi!

During our two days in Delhi, we were entertained by Kailash and Kumal Chaursia, who took us to see some of the construction that was taking place in the city - the underground, the fly-overs and the new shopping malls. Imagine, a Marks and Spencer's in a beautiful mall in South Delhi.

Rested and ready for action, we flew to Guwahati, where we were met by our car and driver who would be with us for 17 days. We stayed a night at the Ashok Brahmaputra so that we could start up the Valley early the next day.

The Trunk Road was in good condition, the Asian Car Rally had started from Guwahati through Manipur, so the road had been repaired. We were heading for Jorhat, where we were to stay two nights at The Manor at Thengal, the ancestral home of the Barua family, a Heritage Building, 15 kms outside Jorhat in Jalukonibari Village.

The next morning, with a packed lunch, we started on a journey to the Nazira Area, to Cherideo Purbut, where I had worked in the 1950's when it was an Assam Company Garden. There we came to appreciate the difficulties that the Tea Industry was facing, especially with small proprietary-owned gardens. Things seemed to be in very poor shape. We were told that they were selling tea at 30% below the cost of production. Sad!

We drove past Nazira but could see nothing from the bridge. The whole area was filled with housing for the oil company. The Amguri Road was so bad that we were advised to return through Sibsagar and the terrible road we had already gone through.

The next day we set out for Moranhat and Khoomtaie Estate and were welcomed by Saurabh and Smita Shankar. We stayed with them for four days ... such hospitality!

We were toured through the gardens of Hajua, Khoomtaie and Doomur Dulling and saw tea that was planted during my time as manager. I was pleased to see that these Estates were in good order, although facing financial challenges. The managers were doing their best to cope with the situation.

The general consensus of opinion is that too much tea of a low quality has been put on the market over the past years, driving the price down. There are a good number of proprietary gardens that have closed down, not being able to pay the labour. This has caused considerable unrest and even violence and the death of a few Tea Estate managers. One occurred in Golaghat only a few days after our departure from Assam. These incidents are unsettling to the whole industry.

In honour of our friend, the late Bruno Banerjee, we visited, in Moranhat, the school for the blind which he founded. This school provides residential care and education for blind children. It is funded by voluntary donations and is helped by Tea Estates in the area. Victor Banerjee has followed in his father's footsteps to oversee the program. We were presented with prayer shawls woven by the students on looms in the workshop of the school.

In the afternoon, we went to the Moran Polo Club and saw the many changes that had taken place there - a new floor and additions. We have on the mantle of our home the Assamese brass dish they gave us and with them, prayer shawls.

Back to Jorhat and The Manor at Thengal for two nights. One of the days we visited the Jorhat Club and found it all looking smart and well cared for. We found in Jorhat that the store Doss &\; Co. still operating and we bought some biscuits for the next stage of our journey.

Since the roads were so much improved, we decided not to spend a night in Guwahati but to travel directly to Shillong. It was a marathon trip, but eight hours later, we were in Rosaville, another of the Barua Heritage properties.

We spent a week in Shillong, and visited with the Richmond family. We couldn't help but toast Bill Richmond, the youngest of Birdie Richmond's sons, who had just been appointed Director General of Police, Meghalaya ...the top police job!

By chance, on the street, I ran into Don Papworth who was living in Shillong. Also by chance we met Iris Macfarlane, the author of the book Black Gold. She was staying at the Pinewood Hotel, where we happened to have lunch.

From Shillong, down the twisty mountain road to the airport in Guwahati and a flight to Calcutta where we spend our last week at The Fairlawn Hotel, our home away from home. As ever, the chaos of Calcutta is indescribable. Fly-overs are being constructed on Chowringee. Work on an underground car park in front of New Market is in progress. Everything adds to the confusion.

On our way home, we returned to Delhi where we lunched with Parki and Gulchan Jauhar, and Frank Wilson. Then another lunch with the Chaursias. It is impressive to see the new tower blocks and office buildings that are springing up around the city.

Once again, we are home and full of memories of a wonderful holiday. We truly appreciate all that was done for us to make it such a success.

Comments

Growing up in Assam late 40's to early 50's

Add new comment