Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Chapter 1: My family and my early days

Category:

Tags:

Visalam Balasubramanian was born in Pollachi, on May 17, 1925. She was the second of three children. Having lost her mother at about age 2, she grew up with her siblings, cared for by her father who lived out his life as a widower in Erode. She was married in 1939. Her adult life revolved entirely around her husband and four children. She was a gifted vocalist in the Carnatic tradition, and very well read. Visalam passed away on February 20, 2005.

Editor’s note: This is Part 1 of her memoirs, which has been edited for this website. Kamakshi Balasubramanian, her daughter, has added some parenthetical explanatory notes in italics.

I am setting out to write down, about myself, my memories, my impressions, and perhaps my desires also. All those who have known me intimately also know my nature, inclinations, likes, dislikes, prejudices and habits. As such, leaving a record of this kind is superfluous, but Papu, my second daughter and third child, whose full name is Kamakshi, has insisted on this for some years now. Radha, my last-born and fourth child, has also occasionally told me to either write down or tape them.

I will, of course, record faithfully my views. I shall also try to be as cogent as possible. With all these resolutions and command of language, still my narration would be amateurish.

***

My earliest memories begin with my grandfather. His love enveloped me. I don't have to elaborate. Really, I can't.

My father was a rich man. Not only in money but in taste and artistic appreciation as well. He had very rich qualities. We were three children in the family. I was the middle one. My mother died when my younger brother, Nagu, was a six month old baby. I was a little over two, and my older sister, Gowri, four and a half.

My father married late. He was 27-28 years old, and my mother thirteen. Their life together lasted roughly seven years. There were no other female members in my father's house at that time, except servants. My father's older sister, a widow, lived in the same town. His brother lived with his wife and children in Coimbatore (Ed. note: Before she was married, Visalam lived in Erode).

When my mother died, my grandfather arranged that my aunt (Coimbatore uncle's wife) will take my brother away with her, and bring him up along with her own daughter, who was just a couple of months younger. She brought them up like twins. Got a big cot, big pram, and big cradle. There is a photograph of her standing alongside these two babies sitting on a table with their two thermos flasks, two silver drinking cups with spouts, in their house even now. My Erode aunt's son (athai's son) was living with them when he was attending agricultural college. He was very fond of my baby brother.

I remember my grandfather taking my sister and me by train to Coimbatore (I don't know how often) frequently to see my brother.

This is a vivid memory from my childhood.

My brother was at the crawling stage. He had brown curly hair. He was fair and delicate looking. He had heavy gold bangles on his wrists. On the mornings we were in Coimbatore, Gowri and I would be with my grandfather on one of the benches in the closed front verandah. We would hear my brother's "Kaa...Kaa..." near the threshold of the passage. My grandfather would then give us both a gentle hug, tell us in a low tone, "இங்கேயே இருங்கோ. அவனை எடுத்துண்டு வரேன்" (Stay put here, and let me bring him).

Here I wonder how we knew that he was one of us, and not a cousin! For an hour or two, my grandfather would be keeping him on his lap while keeping us both also close to him. Whenever we sat in the same cot or bench with my grandfather, we were invariably leaning on him. He never objected. I think we always spent only one day in Coimbatore.

Although we had extremely faithful and devoted servants in Erode, my father and grandfather rarely absented themselves from the house for long. My grandfather left the Erode house only for the purpose of seeing my brother in Coimbatore. He never left it otherwise.

My brother came to Erode when he was nearly three. My uncle was very attached to him. Both my father and my uncle used to travel between Coimbatore and Erode very often. My brother was a quiet child. Soft and timid. Never gave any trouble. For the matter of that, we three were never boisterous, mischievous or destructive. We were over protected.

My father was practically the head of the family, even though he was the youngest of his siblings, because he had originality, earned a lot of money. In fact, his money lending business brought him more money than he wanted to make. So, he put in his own money and began doing business on his brother's name. My uncle had five daughters by then, so my grandfather and father wanted to provide for their marriages! My father may also have wanted to reduce his income tax without curtailing his business.

Still, my grandfather commanded respect and held authority. My father always said that பெரியவர் இருக்கார். எனக்கு யானை பலம் (having his father was like having the strength of an elephant).Till the age of six or seven, my grandfather used to give us our daily bath and give us all our meals himself. On occasion when Kandappan (one of our family's staff) bathed us, my தாத்தா (thatha grandfather) would dry us with the towel paying special attention to ears, nose and between toes. Oil bath and braiding our hair was done by any cook (it was usually a female cook) who was working with us at the time.

On such rare days when there was no woman cook in the house, Kandappan would take Gowri and me with our hair oil, comb, all the gold jewels (நாகர் naagar and ஜடைக்குச்சு jadaikuchu - traditional jewellery for hair adornment of those times) to the house next door or else to one cousin of Lakshmanan's to have our hair braided. People would slyly remark that Kandappan sat watching over the gold - both what was lying loose to be used, as also the ones we were wearing on our persons. It was a tricky situation, but Kandappan managed it.

It seems my mother brought a cow and a woman cook as part of her dowry, and after that, there was always a cook and cows in our house. It was not so before that. My father had to change cooks several times. It must have been trying but we never felt it. There were casual cooks who could be employed till a full-time cook could be arranged.

***

Of the three of us, my sister Gowri did not fall sick as often as my brother and I did. But she always had thyroid and tonsils problem. My brother was also very weak and pale always. He too had tonsils worrying him.

To my father the very word ‘tonsils' was a cross to bear all his life. He never got over his own feelings of guilt in the matter of my mother's death (who died when she was nineteen years old). It was my grandfather who took most of the initiative in my mother's tonsillectomy, having got my uncle's second daughter, Kamalam, successfully operated upon.

It seems my mother was complaining of difficulty in swallowing, eating and general lassitude, which were attributed to her tonsils. My father blamed himself for not speaking to the doctor, not caring enough about whether she was to be treated only that way, for taking her for granted, not realising that her death will deprive us cruelly, and more than all those things, for not telling her parents of the decision in advance. He did not forgive himself for that folly. It rankled.

When my grandfather arranged for the surgery, my father merely lent his support by providing blocks of ice, money, transport, etc. There were other people who were nervous and slightly diffident. They were there with her in the end. I think there were four or five men helplessly watching her die. They were Kandappan, Sarwar Khan, Mohammed Batcha and one Subramanian (family staff members). One Santhanam also may have been there.

My father was full of confidence then. Everything worked for him. Nothing went wrong. Nothing could go wrong! He was the master. That arrogance and confidence blew up in mid-air leaving him to atone for the loss of his wife for the next 26 years, when he himself died.

After my mother's lifetime, he lived only for us. Nothing else mattered for him. He never, never lay down on a bed, not even a bedsheet, but only on a mat even when it was cold, raining and damp. Also, he never celebrated any festival himself. He bought several shelves full of crackers and lots and lots of clothes for Deepavali. He gave new clothes to his sister, her sons, besides all the servants at home and their families. He himself never wore any of it on that day.

***

Talking of childhood illnesses, I used to get fevers, measles, whooping cough and herpes. Also allergic rashes. Sometimes my thatha would try home remedies but mostly my father would get Dr. David to come and see us.

This Dr. David was an integral part of our early life. He was a popular doctor. Many rich merchants in and around Erode were his patients. As was the custom of those days, he used to drop in for a chat at their places while going on his morning/evening rounds. He was always formally attired during his working hours. He employed his wife's brother as a compounder. That man Johniah was a study in character! Very quiet and silent. Deaf. People would invariably remark that if there was a man who never hurt another of God's creations, it was Johniah.

Though my sister rarely fell ill, she once developed a fever that suddenly shot up the next day, rising beyond what the thermometer would record, and she began to have fits. She must have been about six or seven. I remember the ice bag hanging from a cross beam to be in place on her head, and my grandfather very, very anxiously sitting by her side. Kandappan, among others, held her legs during attacks of convulsions, and a number of doctors kept coming and going. I think by evening her fever subsided but the next day she was hyperactive - completely unlike her - and slightly unbalanced. It took her about a week to become normal. That day stayed in my father's memory, without fading.

Most people liked Gowri because she was chubby, very innocent, quiet. Her intuition and quickness of mind never surfaced noticeably.

As a child, my brother was very delicate. He had tonsils worrying him continuously all the time. Nearly every other day he would develop a fever, and Dr. David had to be summoned. My father nicknamed my brother "Temperature Iyer." An attack of typhoid, which relapsed twice after the first one - making it three in all - as a long period of sickness that he suffered when he was about 5, I think.

He lay there quietly. Submitting to anything that was tried\; whether it was "sweating it out," swallowing very bitter pills by some indigenous method, quackery, or our own doctor's medicines and a strict diet of barley water with milk or aerated soda water and milk. Naturally, my grandfather and father were very worried. There were no grandsons for my grandfather by his sons until my brother was born. For that, my father and mother made a pilgrimage to Rameswaram - there being a belief that those who desire a son should go to Rameswaram. Thus, after my mother died, my father put all his dependence on God in the matter of my brother's well-being. After that bout of typhoid, my father had Mrithyunjaya Homam (fire sacrifice for victory over death) and Ayushya Homam (fire sacrifice for long life) performed in Nagu's name for some prescribed period.

***

Right from the days of which I have only faint memory I remember my grandfather praying continuously. He woke up quite early. He would sit in his கயிற்றுக்கட்டில் (kayitruk-katill rope cot),, and with his hands clasped, he would be reciting some prayer for half an hour.

He never said any prayers aloud. Only his lips moved. Continuing the prayers, he would walk up to two pictures of Krishna Bhagawan. தொட்டுக் கண்ணில் ஒற்றிக்கொண்டு நேராகமாட்டுக் கொட்டகைக்குப் போய் பசுக்களின் பின்புறம், துளசிமாடம் இவைகளை வேண்டிக்கொண்ட பின்னரே அவர் நாளைத் தொடங்குவார். (He would touch the pictures, put the hands to his eyes, go straight to the cowshed to offer worship to the backs of the cows and the Tulasi or the sacred basil plant. Only then would his day begin).

Every day he would water that Tulasi and sprinkle that water on himself and on Gowri and me, till Gowri took over that at the age of 10 or so. He used to break a coconut and wave camphor for the pictures of Krishna on Friday evenings. That also Gowri took over then.

Those two Krishna pictures were very dear to him. They have been in the family since my eldest அத்தை athai (thatha's first child, my father' sister) was born and is still there in the same place and position in my brother's house. (That house has been sold.)

My thatha used to recite Sahasranamam at appointed times, and at others kept repeating ஸ்வாமிநாமம் swami namam (God's names). He used to draw deep breaths, and say aloud "Krishna... Vaasudeva..."

I have heard it said my paternal grandmother (whom I am said to resemble very closely) had a very sweet, melodious singing voice. She used to sing ஸ்தோத்திரங்கள் (stotrangl religious verses) while beginning her day's work at dawn.

My grandparents were early risers. My father also woke up early and was out of bed by 4.00 a.m. He never used any ஜமக்காளம் (jamakkalam durrie), mattress, pillow or bedsheet for sleeping after my mother died. He would never lie on a cot either. He used a piece of wood called தலைக்குயரக்கட்டை (thalai-k-uyara-k-kattai block of wood, raised on two symmetrical pieces to the height required to support the head while lying down)\; it was smooth and polished on all sides, corners, with rounded edges. One or two were always to be found in most houses. This was to serve the purpose of "madi" (retaining purity of person, as many materials, once they are washed, are seen as "impure"\; wood, metals, and stone are believed to be beyond being rendered impure) because a cloth or silk cotton pillow was taboo for use during daytime, or heavy bound books were his head rests.

Until my mother's sudden death, my father, it was said, used to decry God saying "சாமி என்ன ஆசாமி," (a dismissive and sharp pun which plays on the word God and Man to mean that God is no man or that God is just another man). But when that loss and grief overtook him, he sought God with such fervour and devotion that he almost became a ஞானி (gnani man of wisdom). He went to temples, and went and saw Sri Ramana Maharishiand Sri Aurobindo. They were only visits. He never sought any audience with them.

He greatly respected his father and looked after him very well. He was the youngest of his brothers and sisters. He was the darling and pet of the family. I think he was very fond of his mother, and admired her for her outspoken ways.

Both my grandparents were sticklers for personal cleanliness. Very systematic in their ways. In my thatha's time, every single article used to be exactly in its place. Not an inch, literally, of deviation. Punctuality was also the same with my thatha. There were animal skins on all the tables, sofas and easy chairs like புள்ளிமான், க்ருஷ்ணாஜினம், புலித்தோல் or சிறுத்தைத்தோல், (deer skin, tiger skin and leopard/cheetah skin in addition to Krishnajinam or Nilgai).There were also horns mounted and placed on the walls. Framed photographs adorned all the walls in tiers.

Pictorial enlargements and painted pictures of my mother in gold, ivory frames were there in several places. All of them were dusted every morning: some of it by my thatha, others by Kandappan. Those that were taken out were put back exactly as before. These included even his two pairs of glasses, pencils and pens.

My thatha must have been a man with fixed ideas. He was himself a lawyer, and he wanted his sons to take up that profession. The eldest, my Coimbatore பெரியப்பா (periappa father's older brother) did his B.L. (or Ll.B, as it is known today) after his B.A. My second uncle wanted to do engineering but was not allowed. He told my thatha it seems that he would fail if he took up a course in law, which he did twice, but my thatha's will was greater, and he also became a lawyer. A good one at that.

That uncle was quite learned. Scholar in Sanskrit, with an excellent command of English, knew Telugu and Malayalam well. He remained a bachelor all his life and joined the Theosophical Society in Adyar, Madras, as a member. He always wore white handspun கதர் (khaddar khadi). He had a very big enlargement of his mother's photograph - later he added his father's also - in his pooja (prayer) room. He made a few trips to Kashi, Allahabad and Gaya to do his ச்ரார்தம் (shrardha obsequies and memorial rites for ancestors, especially parents) commitments.

I was very fond of my father's brothers and sister. We never saw one of my father's sisters because she had quarrelled with my grandfather and stayed away.

My grandmother, too, lived apart from my grandfather. The version I've heard is that my thatha was stingy. He never liked to share anything with anybody other than his own children. He did not deny his children as such. He kept them in comfort but he never allowed luxury or waste. Whereas, it seems my grandmother could never make anything in small or just sufficient quantities for the family. She revelled in sharing everything with neighbours, and giving away large quantities of leftovers to beggars. This was a matter of constant quarrel between them.

I've also heard my father and Coimbatore uncle say that my grandmother used non-cooperation methods to hinder her own sons' attending school/college on important days like exams, inspections, etc. My grandfather took it upon himself on such occasions to ignore her and do whatever was necessary to send the boys to school. My father always said, "One was a demon, the other was a devil. "The story goes that when my grandmother left, she removed her தாலி (thali the ritual sacred yellow thread women in southern India wear around their necks to denote their marital status), and threw it at my grandfather, which he quietly picked up. I have heard (whenever people spoke about them) that she shouted at and scolded my grandfather, but everyone said that my grandfather never raised his voice, nor retaliated.

Anyway, my thatha cut off that daughter and Madras uncle in his will. My father used to visit his sister as well as his mother who lived with daughter in Tanjore. He also sent them money without my thatha's knowledge, against his wishes. My thatha suspected/guessed as much but never caught my father.

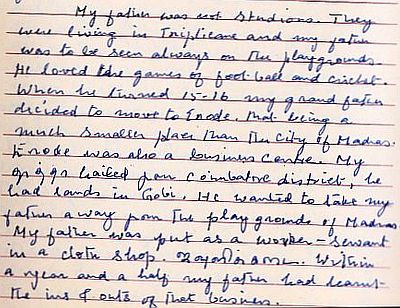

My father was not studious. When his family was living in Triplicane in Madras (now Chennai), my father was to be seen always on the playgrounds. He loved football and cricket. When he turned 15-16 years old, my grandfather decided to move to Erode, that being a much smaller place than the city of Madras.

Erode was also a business centre. My thatha hailed from Coimbatore district, he had lands in Gobi. He wanted to take my father away from the playgrounds of Madras. My father was put as a worker-servant in a cloth shop. ஜவுளிக்கடை (javuli-k-kadai cloth shop).Within a year and a half, my father had learned the ins and outs of that business. He opened his own shop in rented premises. His father - my thatha - had perhaps recognised his capabilities, and gave him capital to set up and start on his own.

By then, I think my grandmother and my grandfather had quarrelled, and she left him to go and live with her second daughter in Tanjore. Meanwhile my eldest athai and her family had come over from their native Tirunelveli/Madurai and settled down in Erode, renting a house near our own. My grandfather was very fond of her and protective of her interests. My father was also solicitous of her always. She used to say that he would send for her at break of dawn, and unless she was there no auspicious event could get started, as he would ask if Pattamma was there. "வாசத் தெளிச்சு கோலம் போட்டா எனக்கு வண்டி அனுப்பிச்கூடுவானே. நாவரணும். அப்றம்தானே மாவெலெ கட்றது. பட்டம்மா வந்தூட்டாளான்னு கேப்பானே." ("He would send for me as soon as the front of the house was cleaned and the kolam was drawn. I had to be there before the welcoming string of mango leaves could go on the entrance to the house. Has Pattamma arrived, he would ask"). She and her sons were always welcome. She never once visited my periappa's house in Coimbatore, and she used to mention that also.

The kind of shining clean house she kept was பயங்கரம் (bayangaram literally 'terrifying' but in this context 'incredible', 'awesome'). Her brass vessels shone like gold.

In a matter of two or three years as a cloth shop owner, my father decided that he will start banking business - money lending - from our own house. Even as a young boy, my father knew many languages. Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam and Urdu besides English and Tamil. He was very young - may have been only 21. Further, he was a Brahmin, not a part of a business community. No one could give him any advice or assistance. And he did not start that new venture right in the centre of the கடைவீதி (kadaiveedi bazaar street) but away from it, in the middle of the Brahmin residential area.

In spite of all these minus points, he became a very successful, very astute, prosperous businessman. He built a small elevation in a corner of the front yard, put grilles and set up his own business which was to make him a very well known, sought after person in and around Erode. He maintained a diary-writing habit from the age of 19.

In the beginning when he came to Erode he was so heartbroken about missing football that he even contemplated suicide! It is there in his diary of that period!

He liked to travel, collect curios, listen to music. Music was a passion with him.

In his collection, there is a grain of rice in which 101 letters are written, neatly enclosed inside wavy lines and stars for a border, complete with its own velvet case, magnifying glass and the glass rod (on which the grain is mounted).

He bought gems, and had jewels made. He learned to look for flawless, high quality diamonds. He chose all the diamonds - every single one of them - personally, and had them set in all the jewels he had made for my mother, for us and the finger rings he wore himself. He had a magnifying glass, a silver box with measured holes -like a sieve -to gauge the size of the diamonds.

***

We did not maintain close contact with my mother's family because my paternal grandfather was most inhospitable. He could never share anything with others- only his children and grandchildren were the privileged ones. He could never tolerate any deviation or disruption of his fixed ways and daily routine. He was averse to entertaining guests and never encouraged visitors. All his chatting was limited to just a few minutes. He confined even his outing only for walking and never any gossip.

So, the only people we had occasion to play with were our own Coimbatore uncle's children. My Coimbatore uncle had six daughters and two sons. They visited us for long periods like two months in summer. Or whenever my grandfather wanted to see his grandson, Nagu, my brother, who was growing up in Coimbatore. But Tippu and Saradham (who became a well-known veena maestro and gave concerts with her husband, Sivanandam), my cousins (from Coimbatore), used to spend quite a long time in Erode every now and then. My father liked Tippu, so he would bring her over, and Saradham would want to come along. My deceased mother's brothers occasionally dropped in when they travelled between Madras and Pollachi.

My father considered himself superior to most others, especially his wife's people, and they could not conform to his family's thinking and ways by any stretch of the imagination. They practically kept an open house. Relatives and friends could drop in any time, and my maternal grandmother's sister, Swarnam, was ever willing and generous with her advice and help. Her husband was a doctor. He was not earning well. My father treated them with contempt.

She had a large establishment to run, what with seven children of her own, a sightless (cataracts) widowed mother-in-law, a widowed sister-in-law with her children, a strict disciplinarian of a husband, cows, buffaloes, man and maid servant. Yet, she found time to learn to do all kinds of needle craft, knitting, crochet, embroidery, tatting, macramé, beadwork, and sewing. And she taught herself English and Sanskrit. She invented her own paper hangings because she was not allowed to buy beads.

She composed many songs. She has had a number of books of her songs printed and published. Devotional songs, mostly in Tamil, a few in Telugu and entire books of songs for கும்மி (kummi traditional folk dance performed by the womenfolk), marriage occasions, etc. She could speak Kannada and Telugu well. She once conversed with a ஸ்வாமிகள் (Swamigal learned and highly revered sage) in Sanskrit. We didn't learn any of those songs ourselves, although some copies of her books were there in our house. When my first daughter got married, and the groom's family sang in celebration, his mother remarked that two of those songs were written by my grandmother.

She wrote articles for periodicals. She composed songs in Tamil, Telugu and Sanskrit and set them to music. There are a number of books of folk songs, poetry and classical songs to her credit.

She would help her neighbours when there was any big celebration and function in their places. She taught some of the local girls who weren't attending school needle work, to sing, read and write even when she was pretty old. She would stretch and rest even as their lessons were on, that being the only opportunity for rest. She visited the Government hospital regularly, always lending a helping hand to a mother of a sick child.

My father judged people by their wealth. He never gave credit to learning, austerity or a contented living. மடாதிபதிகள் (matadhipathigal heads of spiritual establishments) and ஸ்வாமியார் (swamiyar ascetics) were all right. He never showed respect for scientists and teachers. He used to say they toiled, and it was for the rich man to enjoy the fruits of their effort. They themselves could not afford it\; it was beyond their means, and they go on to do more research.

Success for him meant only earning money. A teacher was a ladder. Others climbed up, while he remained where he was. These being his views, he never saw the talents of my maternal grandmother. There again, of her three sisters, one (Kanaka Paati) was very rich, with big bungalows in Madras, Kodaikanal, and Bangalore, two big cars, dogs, cows and servants. My father admired everything about them (her and her family). He attributed their success to her Kanaka Paati's abilities.

All the sisters had got married by the age of 9 years. They never went to school but all of them could authoritatively sit among musicians and musicologists and discuss points on an equal level. One of them was nearly always asked to sit on a panel of judges/selectors for Tamil short story, essay, literary competitions. She was quite famous as குகப்ரியை GuhaPriyai, her pseudonym. Both she and my grandmother used it for their writing. Later my grandmother changed it slightly to குகப்ரியா GuhaPriya.

***

My sister's wedding and my own weddings were huge affairs. Main events lasted five days, relatives arriving before that, and க்ரகப்ரவேசம் (Grihapravesam entering the husband's home for the first time) in the groom's place after that. My father commanded a veritable army of suppliers and managers. People were accommodated in four, five houses. Bags of rice, dals, cartloads of milk were to be seen arriving. My பாட்டி (paati grandmother) and her (poorer) sisters oversaw all the cleaning, stacking of all these stores from weeks before the celebrations. Right from making crushed betel nut with all the aromatic ingredients and coloured fragrant quicklime filled in fancy bottles, they planned and did most of these things, prior to the main celebrations.

They had responded to my father's letter asking them to come and do all this work. But he made it appear that they swarmed down to enjoy themselves. GuhaPriyai was a freedom fighter and wore only handspun khaddar. She wouldn't accept any silk saree. I don't know if she or her daughters (small children) were given any gifts.

While my father failed to appreciate the help extended by the three sisters, when their other rich sister came to attend the wedding proper and gave some tips to the cooks to make பஜ்ஜி (bajji fritters with vegetable filling, a snack), my father kept on extolling her knowledge of the "tricks of the trade."

Nearly 25 years later I asked the youngest of them (she was the only surviving sister then) why they put up with such treatment and still came to see us. She dismissed it saying, "அவருக்காகவா வந்தோம்? குழந்தைகளை விட்டுவிட்டுப் போனாளே, அவளுக்காக வந்தோம்.("Did we come for him? We came for her, the one who went away leaving her children behind"). She shook her head in a way as if to throw that thought, that memory, out.

Go to Part 2

______________________________________

© Kamakshi Balasubramanian 2015

Comments

Add new comment