Latest Contributions

My recollections of my city of birth-Rawalpindi

Category:

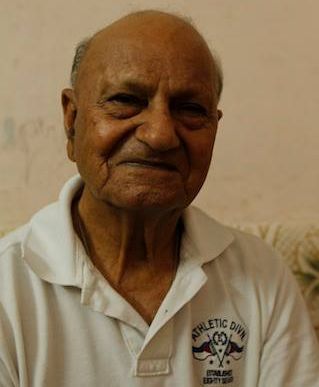

Yashpal Sethi was born on September 7, 1931 in Mohalla Shah Chanchrag, Bazaar Sarafan, Rawalpindi, and moved to India after the Partition of India. He joined the Punjab National Bank in 1953 and retired from the Bank in September 1992. He returned to Pakistan in 2006 to visit Murree, Rawalpindi and Lahore, when he had a memorable time visiting various places, including his ancestral home, which today is a commercial complex. Now he lives in Yamunanagar, Haryana and is quite active on social media such as Facebook.

Editor's note: This article is based on an interview conducted by Gurpreet Singh Anand in 2013, and is presented as a report of this interview. Additional material has been taken from Yashpal Sethi's blog http://yashpalsethi.wordpress.com/

Gurpreet was born in India to parents who fled from Rawalpindi and Murree, where the family had cloth shops, as ‘refugees.' His father, though from a business family, was a full time member of the communist party and a freedom fighter. His father died when Gurpreet was 10 years old, leaving behind a diary of the events in 1947\; Gurpreet has always been intrigued by this diary. Gurpreet, now an avid traveller and businessman, keeps searching for people who were traumatised by the partition of India. He interviews them to record their memories, and keeps in touch with people of similar interest in Rawalpindi.

Yashpal’s family

His ancestral home was Bhera in Sargoda District, now in

His great- grandfather Ishar Das Sethi s/o Shanker Das Sethi was a leading petition writer in Bhera. His grandfather was one of three brothers. The eldest was Bhagat Ram Sethi, a bank officer, the second was his paternal grandfather (Dadaji दादा जी) Ram Das Sethi, and the youngest was Raghbir Lal Sethi. Dadaji had one sister who died young, before she got married.

Dadaji was normally tolerant, and seldom lost his temper, though it is said that he used to be obstinate in his childhood and was called bhandi (quarrelsome). Dadaji had a whitish complexion. He was a little taller than his grandmother was. He always kept himself busy. He used to recite some old Urdu poetry epics (Bulle Shah). He normally never interfered in any domestic matters.

Dadaji was in the habit of smoking a hookah. Once in a while, Dadaji asked Yashpal to bring tobacco for the hookah from Purana Quila, a place closed to their residence\; otherwise, normally, Dadaji himself used to bring the tobacco of his own taste. Sometimes, Dadaji used to blend the raw tobacco to his taste. Dadaji was a very simple and humble man. He used to wear a white Pagri (headgear of thin cotton cloth- malmal), white shirt and white salwar all starched.

His grandmother (Dadiji दादी जी) was Gur Dai daughter of Hazura Mal Kohli, who was a very rich man. She had two brothers and a sister. She was of a short stature, very beautiful, with small hands and feet. She had very fair complexion. She was very soft spoken. She used to keep a small wooden comb and a piece of dandasa (a tree bark used for cleaning teeth) in her side pocket. He never found her bickering with anybody. She was majestic in the real sense. She used to wear very neat and clean clothes all the times.

His maternal grandfather (Nanaji नाना जी) was Sarab Dayal Sahni, who lived in Malakwal in district Gujrat. He died young, and the marriages of all his children were solemnised after his death.

His maternal grandmother (Naniji नानी जी) was Har Dai, sister of Manohar Ram Kohli of Malakwal, one of the two big personalities of the town. She had a fair complexion. She used to wear a tamba (a piece of cotton cloth used as single dhoti) in place of ‘salwar' at home. Though she was not harsh but her manner of speaking was not so pleasant, perhaps because of because of her village culture. Otherwise, she was nice, sympathetic, caring and hardworking.

Her main work was managing the milk. She used to put the milk in the earthen pot (called Kuni) in the morning and put it in the small window hearth in the wall covered with a door of wooden flats so that the air and the smoke could pass through and the milk could be saved from the cats. She used to put this milk pot for boiling on a dung fire in the morning for the whole day. Thick malai (cream) used to form on top of the milk, which used to become yellowish by the evening.

She would never allow anybody to drink this milk. She would curd this milk at night, and early in the morning, when everybody was asleep, she would churn this curd with a long heavy wooden beater (madhani) tied with cotton rope on a wooden stand in a clay pot called matki with her both hands till the butter began to swim on the chachh (buttermilk). She would take out the butter from it and put it in a separate pot, and the chachh in a separate pot. The chachh was served during the day\; the butter was mainly used for the chapattis. Fresh butter with basi (stale) roti and chachh were served as breakfast. The unused butter was converted into ghee by heating it. This ghee was used in pulses and vegetable for dinner and lunch.

Apart from tending to the milk, Naniji sometimes used to make chapattis during the day. Otherwise, the rest of the housework was done his mamis (aunts). There was complete unity in the family. He never found them quarrelling or irritated.

His father, Achraj Lal Sethi, an iron merchant, had three sisters and two brothers. His mother, Karma Wali, had two brothers and two sisters. She knew Gurumukhi, which she learned while going to Gurudwara in her hometown. In those days, Punjabi families learnt Gurumukhi, and some had Guru Granth Sahib, a Sikh holy book, at home, which they used to pray to even though they were Hindus.

Yashpal had four brothers and four sisters. He is the oldest child of his parents.

Yashpal's memories

His memories go back to early childhood years from which he has many anecdotes to share.

He remembers his father vividly images as a tall man who would wear a white turban with Straw kula or Zari kula, which is kind of a cone on the head with golden (zari) thread, a long shirt and a salwar. His clothes were always starched and pressed. He was a very soft spoken who instilled in his family a spirit of self-sufficiency. He would insist that one should not borrow but hard work in life and buy what is needed. He was fondly called Bhapaji.

At the age of five, Yashpal was sent to the local school in Murree, which is also called Koh-Murree. He recalls a school building, which was a single story with five rooms in a row with veranda in the front. In those times, people from Rawalpindi also used to have shops and houses in Murree, as it was a popular British town.

His other memories of this school are of Bansi a Chabari Wala,(one who trades by carrying goods in a big basket and stopping where people want to shop his wares) who used to sell orange and green coloured Golian (round candy) locally made from sugar with some flavours, such as sweet, imli (tamarind), etc. One paisa (Ed. Note: 1 rupee = 64 paisa) was sufficient for buying these things, as a single item could be purchased for a dhela (half paisa)

He has many pleasant memories of Murree. He recalls The Mall in Murree, which had huge showrooms where only Britishers were allowed to shop. There were two cinema halls. After nine, at night there were two shows when English pictures were shown for the white people.

An incident that happened on The Mall as he was walking towards the Pindi Point is etched in his memories. The peaches hanging from a tree as he was walking were too tempting and he plucked a peach. The moment he plucked one, he had to hear unintelligible verbal abuse in English. The owner of the house, a British woman, was abusing him. He ran for his life on the Mall towards his house, panting and breathless.

Later, Yashpal shifted to Rawalpindi along with his family. He was admitted to Mission School near the Rose Cinema. Going to the school, recalling his days of walking to the school, brings back memories of this cinema hall, which had a huge hoarding outside that periodically showed the Allied Forces' progress in World War II.

He remembers the rainy season in Rawalpindi as a playful time. When walking into the school, the children would float their takhties (wooden writing plank) in the water like boats. At the other end of the water tank, the children would take out their takhties and shout together in rhyme Suk ja meri takhti suk ja (get dry my Takhti, get dry) until they became dry.

The medium of instruction was Urdu in Persian script for boys\; girls used to go to separate schools.

One of his teachers was six feet. He would punish who indulged in pranks the kids by picking them up from both the ears, up to his height, and then throw them on the floor abruptly. Needless to say, Yashpal dreaded this punishment, which he never got. When a child was very naughty, the master would ask them to become murga (cock) outside in the sun. Becoming murga consisted of putting his arms in between the legs, and catching the ears, with the buttocks upward. Very painful!

Queen Victoria's birthday was celebrated in the school by giving each student a ladoo on her birthday.

Yashpal does not remember why and when he was sent to Malakwal, his Naniji's hometown, which was on the Lalamusa -Sargoda railway line. He studied there up to class V. The school uniform was a long shirt with salwar.

Malakwal had no electricity. There were kerosene lamps to illuminate the streets. In the evening, a man used to come with a basket of kerosene lamps, which he would light one by one and put them in the poles. In the morning, he would come to collect these lamps from the poles.

Childhood memories of celebrations of weddings bring to the fore his uncle's wedding, when the baraat (groom's group) went from Rawalpindi to Bhera, a small town in Sargodha. The joyous Punjabi wedding where both the host and the guest mingle in singing and dancing Pathoar's Mahiye and Dole are without parallel. Punjabi's folk songs were sung by male guests wearing Pugga (turban) and Angrakhey (like a large Muslim coat). Female guest singers were also there. The most popular song of the guest singer was Suve way Chure Walia Mai Khaini ha kar chatri the chha main chhaway behani ha.

Some baraaties (members of groom's group) were mischievous. They started demanding a particular food item again and again, so that the host may have to cut a sorry figure, but the hosts were fully prepared to this eventually and were determined to manage everything. If there were delays in meeting their demands for a particular item, the baraaties would try to hoot the hosts but their demands were nevertheless met.

At another wedding, the baraat returned from Rawalpindi to Malakwal with mami (uncle's bride) after the marriage at night. However, mami entered the home in a Doli in the morning under Tarow ki Chhaw (before the stars vanished). Doli was a small tent type for sitting, made with bamboos and covered with red cloth. It was tied with two strong long bamboos and shouldered by four persons (Mehraz).

When his massi (mother's sister) got married, the baraat came from Rawalpindi and stayed in Malakwal for three nights. They were housed in a nearby cotton mill. The baraatis slept on the carts and beddings were provided. Bed sheets were spread on the ground and the baraatis used to sit on the sheets for lunch and dinner. Halwa was the first item to be served. Sweets were also given with the lunch or dinner in addition.

The Second World War ongoing at this time everything was rationed including food and clothes. Special permits had to be taken to obtain food for weddings. When there was a non-cooperation movement in 1942, all the shops were closed voluntarily for over month, and there was scarcity of good stuff. There was a little relaxation on the wedding of a girl with the permission of the Vyapar Mandal (business association.)

His remembrance of early life spent in Rawalpindi brings forth Janam Ashtmi. He and his friends would decorate and design the Lord Krishna Jhanki (tableau) with his photos and statues illuminated with small bulbs. Neighbourhood people of all ages would come and pay obeisance to Lord Krishna.

He recalls Jawahar Lal Nehru's visit to Rawalpindi in June 1946 on his way to Srinagar when he was stopped at Kohala and was not allowed to enter the state by Hari Singh, Maharaja of Jammu &\; Kashmir. Rawalpindi used to be the gateway to Kashmir. From the plains of Delhi, Calcutta, Madras and Bombay, one had to pass through Rawalpindi to go to Srinagar. He also recalls when Gandhiji stayed at Mohan Pura, behind Rose Cinema, where hundreds of people came to have their darshan (see and meet).

The day in March 1947 when Rawalpindi became a battleground between Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims is etched in his memories. Yashpal recalls that he was in Sardaran Da Bagh (a beautiful garden of Rawalpindi stretched in many beeghas of land with grassy lawns, large number of palm trees, magnificent Gurudwara and Shiv temple on one side), when he heard commotion all around. He was preparing for his Class X examination, and he could not understand why people were running helter-skelter. The area surrounding Sardaran Da Bagh was Muslim dominated and their main masjid (Jama Masjid) was just behind the Bagh. He managed to rush through all the way to reach his house, where everyone heaved a sigh of relief.

Rawalpindi city was mainly dominated by Hindus, and they had the main business stake. In the surrounding villages the Muslim were in majority and thousands of Hindus men, ladies and children were slaughtered. Their shops were looted. It continued for many days. Everyone was confined to his area. The Hindus who were living in the Muslim area were either murdered or luckily escaped without their belongings. However some Muslims saved their Hindu neighbours and vice versa. Mostly the attackers were from other localities.

The exodus of Hindus and Sikhs had begun, even as all around the town and outlying rural areas of Rawalpindi their shops and houses were looted. Many men were killed and their women abducted.

A few days before the country was to be partitioned it was declared that Lahore would go to Pakistan. Hindus were disappointed as Lahore was predominately a Hindu area, though it did not affect Yashpal's family because Rawalpindi had already been declared a part of Pakistan.

His final Class 10 exam was held in D.A.V. College in June 1947. The attendance in the examination hall was very thin, as many families had already shifted to India. His own extended family members, including some of his sisters and a brother had shifted to Palampur (in India) temporarily. The rest were waiting for the situation to normalise. It was thought even after Partition, things would become normal and the family would continue to live in Rawalpindi. But the situation was becoming worse day by day. All the business establishments were closed. People were confined to their four walls.

From Delhi, an Urdu newspaper asked all the Hindus who were residing in Pakistani area to hoist saffron flags on their houses on 14th August 1947, the day on which Pakistan would come to existence. He was the lone Hindu in the area who decided to hoist the saffron flag. Some officials of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) asked Yashpal to persuade his parents to migrate to Kashmir.

The whole town was in panic and fear. The local MLA, Kale Khan, assured Yashpal's father not to panic and to sell their shops in Rawalpindi and Murree to him. His father had no option but to accept the proposal. Yashpal recalls having shifted to their distant relative Mr. Prem Bhasin's home in the nearby mohalla (locality) of Hindus. This was a virtual camp, as Yashpal's family had become refugees in their own land.

A few days later, a military truck of 7th Gorkha regiment had arrived. An arduous journey with Som Bhasin, a family friend had begun to Palampur in India, leaving behind Rawalpindi the place of his father, his father's father, and his fore fathers forever.

Near Lahore, the military truck stopped for the night.

Yashpal says: When I reached Lahore in the evening, one of the soldiers asked him if I wanted to visit Lahore City, I could accompany them. I went with the soldiers in Lahore city, as they were to deliver meal to their colleagues in other camps. Though it was a hurried drive in the city, I found the life was very normal for those who were living there now, and were now called Pakistani.

Next day, we passed through Amritsar and Pathankot to reach Palampur. My parents and two brothers were still in Rawalpindi.

Diwali festival was fast approaching (Ed. note: Diwali was celebrated on November 12 in 1947) but there was no sign of his parents' return. One day suddenly the family was told that a military truck had left Lahore for Rawalpindi, to bring the rest of the family to India. And so it was - his parents and two brothers joined them before Diwali.

Financially broken, a new life had begun in a land where social and individual identities had been lost forever and only one new identity stuck for the rest of their life - ‘refugee'.

© Gurpreet Anand and Yashpal Sethi 2013

Comments

Add new comment