Remembering Jawaharlal Nehru

Category:

Tags:

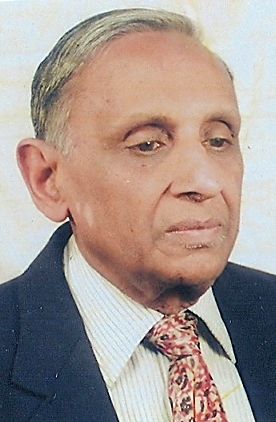

R. C. Mody has an M.A. in Economics and is a Certificated Associate of the Indian Institute of Bankers. He studied at Raj Rishi College (Alwar), Agra College (Agra), and Forman Christian College (Lahore). For over 35 years, he worked for the Reserve Bank of India, retiring as the head of an all-India department. He was also Principal of the RBI's Staff College. Now (in 2019), in his 93rd year, he is engaged in social work, reading, and writing. He lives in New Delhi with his wife. His email address is rameshcmody@gmail.com.

In 1912, the 23-year-old Jawaharlal Nehru returned to India after seven years as a student in England, where he was first a schoolboy at Harrow, then an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge, and lastly at the Inner Temple in London for his bar-at-law. His father, Motilal, a towering leader of the Allahabad bar with a flourishing practice, expected that the young and western-educated Jawaharlal would start as his apprentice and eventually emerge as a barrister of national fame.

But Jawaharlal's life took an altogether different turn. He found law uninteresting and the atmosphere of law chambers boring. There is no record of the number of briefs he took up or of how much he earned as a lawyer. All that we know is that he didn't stay long in the profession.

During the early days after his return from England, he spent time mostly in the company of English families in Allahabad. But very soon, he started drawing inspiration from the lives of great Indians like Tilak and Gokhale. After the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in April 1919, he turned into an uncompromising opponent of British rule over India.

Motilal was a member of Indian National Congress without being actively involved in its activities. Jawaharlal plunged headlong into the struggle for India's freedom, dragging his father along with him. Unlike Mohammad Ali Jinnah, a leading figure of Bombay bar who too was in the Congress then but without ‘spoiling the crease of his pants', Jawaharlal cast away his and family's western clothes. In fact, the Nehru family made a Holi of those clothes by burning them publicly, retaining just one suit. This was the one which Motilal had got specially stitched by a Saville Row tailor in London, and which he wore to attend the 1911 Delhi Durbar, to which he was invited as an eminent citizen of United Provinces.

Soon after, Gandhiji came on the scene, and Jawaharlal became his devoted disciple. The year 1921 was a watershed year in Jawaharlal's life as he performed his first pilgrimage to an Indian jail.

Even in pre-independence India, Jawaharlal became obsessed with China. He cultivated a relationship with the Kuomintang regime under Marshall Chiang Kai-shek. Then after independence, Nehru quickly warmed up to the Communist regime under Mao Zedong and Zhou En-lai. Nehru's China obsession helps us understand his last days.

The China shock

In December 1950, a few days before his death, Sardar Vallabhai Patel, Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister, warned Nehru against the Mao-Zhou regime in China. Nehru ignored the warning. India became the first non-communist country to extend recognition to the Communist government of China, even as many Western leaders described the Chinese leaders as the bandits of China.

Nehru became a friend of Zhou's, basing the friendship on the principle of peaceful co-existence between countries with different ideologies, epitomized by the word Panchsheel and by the slogan Hindi-Cheeni Bhai Bhai (Indians and Chinese are brothers). Nehru lobbied for the communist government to inherit the permanent membership of the U.N. Security Council in place of the Kuomintang regime.

But alas, the cordial relations between Nehru's India and communist China didn't last long. Early in 1959, India extended a warm welcome to Dalai Lama, Tibet's spiritual leader and virtual ruler of Tibet, who had fled from his home and seat of power in Lhasa under pressure from the Chinese government. Nehru assured him of his safety and security.

Around this time, the Chinese started intruding into Indian territory, across the McMahon Line in the Himalayas, the agreed border between the two countries. Chinese troops occupied territories that the Indians considered to be theirs. The Indian government considered the incursions as acts of aggression.

In this charged atmosphere, Zhou announced he was coming to India. He landed in Delhi on April 18, 1960. I received a pass for the reception of the Chinese leader at Palam airport, and took my 4-year-old son, Ashoka. As was typical in those days, security did not shield leaders from the public and we mixed freely with all, including some VIPs who had gathered there. As Nehru was waiting for the guest to land, he (known for his love of children) held Ashoka, and affectionately dragged him along several meters before letting him go.

In his meetings with Nehru and other senior Indian leaders during the visit, Zhou insisted that China had not occupied any Indian territory. He visited Morarji Desai and Govind Ballabh Pant, among others, to explain China's viewpoint. (He skipped V. K. Krishna Menon, India's Defence Minister) who was considered a controversial personality even by Indians.)

But all Indian leaders rejected Zhou's views. He returned empty handed.

In 1962, the Chinese army began more serious incursions into Indian territories. When Nehru heard the reports of these, he angrily ordered the Indian army to "throw them back." Such bravado proved counterproductive. In October 1962, the Chinese launched a blistering attack across the Himalayas, inflicting a humiliating defeat on India.

Nehru had misjudged on so many counts. His idealism had failed to recognize the crucial importance of power in international relations. His judgment failed to acknowledge the power imbalance between China and India.

The last days

In May 1964, Nehru renewed the effort to solve the 16-year-old Kashmir problem, which he had let fester all this time. Having imprisoned the Kashmiri leader Sheikh Abdullah since 1953, Nehru now ordered his release. From his house arrest in Kodaikanal, Abdullah came as Nehru's guest to the prime minister's home at Teen Murti House. Ironically, the two of them were old friends, and they met in a warn reunion.

Abdullah's press conference gave the world a sense of Nehru's fading health. He found Nehru sincere and affectionate as ever, Abdullah said, but physically he was a pale shadow of his past.

In another incident in May 1964, a Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) attended a meeting of the Planning Commission, which was chaired by Nehru at Teen Murti House. Nehru was not well enough to go to Yojana Bhawan, where the Planning Commission was located. Describing the proceedings in melancholy words, the RBI official said, "It took Nehru nearly 10 minutes to say a few words, with frequent stops to catch his breath." The meeting was short. "We were anxious to save him further effort and went out sadly, leaving him still sitting at the big table."

Nehru brought back Lal Bahadur Shastri as minister without portfolio. From then on, Shastri, who had earlier resigned as Home Minister under the Kamaraj Plan, assisted Nehru in his work. This development was Nehru's first public admission that he was not well. He tacitly also indicated that he wanted Lal Bahadur to succeed him.

Soon thereafter, Nehru addressed a press conference at Teen Murti House. A journalist asked him why he did he not formally anoint a successor in his lifetime. Nehru replied, "My lifetime is not going to end soon."

A day or so later Nehru went for rest and recuperation to Dehradun, his favourite resort in the foothills of Mussoorie. He had a very warm meeting there with his old friend Sri Prakasa, a person of his age and a renowned Congress leader who had held several diplomatic and political positions but had retired by then. Sri Prakasa, seeing Nehru's state of health, ventured to suggest that he should consider retirement, having served the country so well and for so long. Nehru just smiled. In his mind the lines of poet Robert Frost-which he had kept for some time on a side table close to his bed-were ringing, "The woods are lovely dark and deep but I have promises to keep and long to go before I sleep."

The Dehradun stay did refresh Nehru. He rejected suggestions that he should stay there longer to gain more strength. Work awaited him in Delhi. He had a simple vegetarian thali meal on the evening of May 26, after which he took a flight to Delhi. Back in Prime Minister's House, he retired for the night in his bedroom.

"So to sleep"

On May 27, I was in a chemist's shop in Connaught Place in Delhi. A stranger told me that Nehru was lying in a coma since the morning\; another stranger overhearing the news commented, "How can that be? He returned from Dehradun only last night, totally refreshed." Without trying to judge which one of the two was correct, I took my car and dashed home, about six miles away. Just I was entering the house, I heard a young lady from the adjacent house saying "Panditji guzar gai (Panditji has passed away)." I instantly broke down.

I switched on the radio (there was no TV then). Melancholy music was playing. In his usual erudite language, President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan paid a touching tribute.

Along with my mother, my wife, and my two children aged eight and five, I drove to Teen Murti House around 8 p.m. Nehru lay lifeless, his face somewhat puffed up. Next day, we watched the body carried on a gun carriage on its way to Shantivan. We stood on the lawns around India Gate, at almost the same spot as the one from which I had seen Gandhiji's cortege passing over 16 years ago. A memorable chapter in India's history had ended. We were not to see the like of him again.

A few days later, I saw a touching documentary produced by Films Division entitled "So to sleep." It showed a sick Nehru delivering his last public speech in Shanmukhananda Hall of Bombay. Many in the audience came out with the sad feeling that they had heard him for the last time.

© R C Mody. Published September 2019

Comments

Add new comment