Latest Contributions

Jal Pappa by Arzan Khambatta

Category:

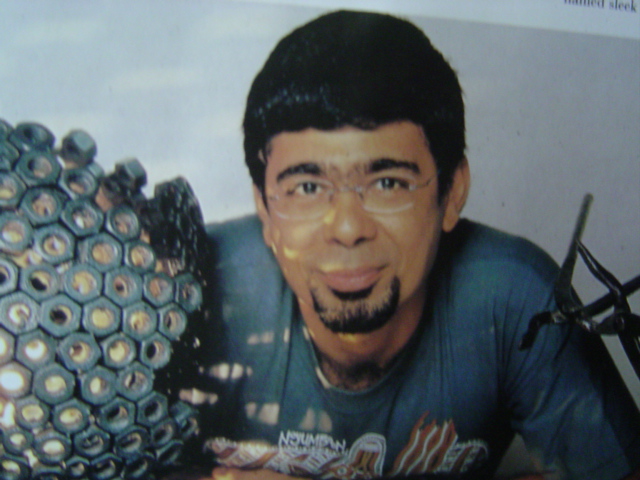

Arzan, an architect by training, makes public sculptures from metal sheets, straps, rods, pipes and various other sections that are twisted, beaten and textured to give the desired effect. He lives in Mumbai. This contribution reflects his Parsi lineage.

y maternal grandfather, Jalejar Engineer, was called Jal by friends and Pappa by his grandchildren.

He was born in 1900 in Bombay. He was one amongst eleven brothers, and the youngest of them all. His parents were Navaqjbai and Dorabjee Bawaadam, but the family name was changed to Engineer, based on his father’s profession. His parents had delegated the burden of bringing up the younger ones to the older siblings, so you can imagine what fun it must have been for the younger kids. An elder brother would definitely be more lenient than the parents would be. So his earlier years were all fun and frolic, even in school.

After school, he went into the military. I do not know what rank he rose to, but even in his retirement, he seemed to retain a military sense of life. All of six foot three, he cut a very respectable figure on the streets, as he was always dressed in starched and pressed trousers, and a full sleeved white shirt. On more formal occasions, such as going to his bank in the Fort area, he would add on a sober tie and coat.

He would collect lot of souvenirs from his various trips abroad. And these would be very precious to him. Like his small replica of the Eiffel tower and a small teddy bear hand puppet he had picked up from England. Even foreign coins would be a part of his collection. On some evenings, he would pick these out one after the other and tell us stories related to them.

He had hilarious stories to tell us. He told us how someone cheated him once on the road in the Fountain area in 1982. Someone came up to him and asked him whether he was interested in buying imported Scotch whiskey, which had been confiscated by the Customs authorities. The price was reasonable amount, and the true Parsi that he was, he could not resist the offer, and bought it. He came home very excited that day. After a shower, he sat down ceremoniously and cranked the bottle open. He first took a whiff of the liquid, which is what he always did. He said true Scotch could be recognized only by its aroma. He was in for a shock! He discovered that what was passed on to him as ‘nectar’ was actually tea water. Of course, the expletives followed with “Arre apra jamana ma aevu nai thatutu (These things never used to happen in our times.)”

He would always reminisce with us about how in one-fourth anna (about Rs. 0.02) he would be able to survive for three days, how he had toured “Velaat” (meaning England) and Paris with my mum for two months by ship for only Rs. 700. How he had shot a pellet in the backside of a macchimaar (fisherwoman) because she insisted on yelling and selling her fish only during the afternoons, which coincided with his siesta.

He was on the first all-Parsi cricket team that played against the British team.

He told us about this cricket match which was being played at the Parsi Gymkhana, between the club and the visiting British team. It was a friendly match and the umpire was a Maharashtrian gentleman. The British were batting, and the umpire gave one of the players out LBW. Not agreeing to the umpire’s judgement, the player asked the umpire “ON WHAT GROUNDS DID YOU JUDGE ME OUT?” The umpire replied “DON’T YOU KNOW? ON PARSI GYMKHANA GROUNDS OF COURSE!”

He also told us about the welcome note that one of the Indian team members presented to the British team on their arrival. Seeing the very fair and red-cheeked Britishers, he proceeded to tell them, “You all look very bloody.”

Pappa loved Khandala. He firmly believed that if he was ailing from any sickness, there was no need to go a doctor – all he had to do was to head out to Khandala for a couple of days and he would be fine. He used to tell us that, in the late 1950s, in the evenings all the Parsis would start out for their walks. They would be dressed to the hilt – the men in a suit and tie and the women in fancy saris. The walk would generally take a break at Behrmjee Jeejeebhoy point, now called Rajmachi point. Here they would enjoy the sunset and then start strolling back to their bungalows or sanatoriums. Sometimes the walk would not be possible, as they would be warned about panthers who were on the prowl. These panthers were a very common sight then, and generally would never harm humans. Pappa said they were kutra khau, meaning they ate dogs only.

Once back at the sanatorium, the large Parsi pegs would emerge filled with “Skotch”. Nothing less would do. There would be wafers to accompany it or even sometimes fried boomla (Bombay ducks). There was no electricity in Khandala those days, so fanaas (oil lamps) were lit all around. There would be a bit of singing too. No TV, no saas-bahu serials, no DVDs, no laptops, no music systems - just pure nature and the humans that inhabited it.

Pappa was very daring, sometimes a bit in excess which would worry my mother a lot. He would get into arguments quite easily and sometimes raise his walking stick to prove his point. But never to his children or grandchildren.

I remember once, in 1975, he woke me up at 7:30 in the morning, and asked me, “Khariya leva avech ke, nal bajar (Will you come with me to null bazaar to buy trotters)?” I agreed and quickly got ready to accompany him. As usual, he was in his crisp trousers and white buttoned down shirt, and carried a walking stick.

We went there by bus. The place was filthy and stinking, and for me, scary. Too many people, too much noise, and I wished I was still asleep at home. We walked up to one shop. Pappa asked the price, took a trotter in his hand, shook it a bit to check its freshness. Moved to another one, liked what he saw, so he said ok. Fixed up the price and asked it to be cut into small pieces. When that was done, he collected the two large thelas (bags), which weighed a ton.

Then, suddenly the vendor asked for more than the initial price settled. Things started getting scarier. Both the vendor and Pappa were shouting at each other. The vendor got down from his perch and started to pull the bags from Pappas’s hands. I kept pulling Pappa away. I said, “Leave it, let’s go home.” He turned to me and asked, “What are you scared of? This fellow?” And proceeded to knock one hard sock with his walking stick on the vendor’s head. That suddenly calmed things down. The vendor said, “Jao, pagal bawa jao, ab tak to khali pagal bawa ke bare me suna tha, aaj dekhne ko bhi mila (Go, mad Parsi, go, until now I had only heard of crazy Parsis, today I got to see one too).”

Active as he was, prostrate surgery slowed him down a bit, but not for long. At the age of 75, he was working for a firm called JD Jones in the Fountain area. I remember him dressing up in his suit, neatly tucking the catheter bag under his coat, climbing on a bus and going off to work.

Knowing he was so fond of cricket, Dad bought a television for him in 1976, when TVs were just becoming common in India. At that time, cricket had only Test matches – no one-day matches. He would be ready and in front of the TV, dressed as if he was actually stepping out to the stadium. He would have his prayer cap on.

Watching him watch a match was hilarious. He would be hunched over, straining towards the TV, with his elbows on his knees. Feet shaking in anxiety. And God forbid if one of the Indian players got out. He would shout SSHHHAAAAAE!, remove his cap and throw it on the floor violently. In the same motion, he would pick it up, flick it a little against his knee and neatly place it on his head, waiting for the next player to come out to bat.

Unfortunately, he spent the last two years of his life in bed, undergoing multiple surgeries for a compound fracture in his right leg. It was terrible to see such a high-spirited person, lie flat on the bed like that. How he must have hated it. This I realize right now, and not then when we saw him.

But, even then he would attempt to play “pisnikot” (a complex card game) with us, and he would sing some hilarious songs of the yesteryears like …

I am an educated tatia,

and I like maja kolmi cha patia,

jolly good senor pestaon,

jolly bad senor pestaon,

Parsi people very mad,

maka sangto gepao.

I remember one more:

One day I was going to school, the teacher called me a big fat fool,

in her hand was a big bamboo, on my head came a big limbo,

now I’m old and weary, drinking wine and whiskey,

now I’m old and weary, but Jalejar is my name.

He passed away on the morning of my 10th standard chemistry board exam.

I blocked out the whole event as if it did not happen.

I gave my exam.

Came home.

Showered, went to the tower of silence.

And then I accepted he had gone.

And then I cried.

_________________________________________________

© Arzan Khambatta 2007

Comments

Add new comment