My Early Memories of Indian Railways

Category:

Born in 1948, I (Anoop Krishna Jhingron) did my M.A. in from University of Allahabad in 1968, and joined Indian Railways Traffic Service in 1971. I retired from the Railways in 2008 as General Manager of Western Railway. After retirement, I have settled around Delhi, where I pursue my hobbies of philately, photography, and reading. Two of my books, one on philately and the other on railway heritage, have been published. A third book on philately is likely to come out by October 2013. At present, I am working on my next book"Life in Railway Colonies."

My association with the railways has been very long, in fact, since I was a young child.

In those days (in the 1950s), all children, particularly boys, normally used to have a fascination for railways, and I was no exception. The place where we were living in Allahabad was located in an area very close to Howrah-Delhi trunk route. There was a level crossing near our area and I, as a small child, often used to stand near the gate and watch passing trains.

As the route was very busy and often shunting of goods trains also used to take place across the level crossing, the railway-crossing gate used to be often closed to road traffic for long durations. The gate was operated by a winch located in a cabin. One of the cabin men was a middle-aged man. He was known as Karela Maharaj\; no one knew his real name. Road users used to shout asking Karela Maharaj to open the gate. Perhaps Karela Maharaj was irritated by this name and would regularly abuse the persons calling him by that name.

My initial train trips, in the 1950s, were for small distances. My father, who had an adventurous nature, liked to visit nearby small places on his off days. There were several small rural places sides located some 15 -20 kilometres from Allahabad, where weekly village markets used to fill on a particular day of the week. One such place was Phaphamau, located on the rail route towards Lucknow, with weekly markets being held on Sundays and Thursdays. It was across Ganga river, which was crossed by a rail-cum-road bridge called Curzon Bridge.

We normally used to go there by slow passenger trains. The journey from Allahabad to Phaphamau used to take about half an hour. My father and I used to travel in third class compartments, which were invariably crowded. Going to Phaphamau was not a problem as the trains used to start from Allahabad, the journey was short, and getting out was easy as the passengers in the compartment would gladly provide all help to those getting out. After all, their exit was going to reduce the crowding.

However getting into the train on return journey was an altogether different proposition. The stoppage at Phaphamau, only a small roadside station, was hardly a few minutes and the trains usually were over crowded. One had to often run from one coach to another to find a place, and we could board the train only with great difficulty.

If we were not successful in boarding the train, the only option was to travel from Phaphamau to a place called Katra in Allahabad by an ikka, a horse drawn carriage where the passengers were required to sit on a wooden platform. From Katra to our residence we used to travel by cycle rickshaws.

At that time, the trains used to have an exclusive small compartment ear marked for suppliers of ice. The slabs of ice could be had by first class passengers on payment. The slabs were kept in the compartments in big iron tubs below the fans and used to cool the compartment. We often tried to enter the ice compartment but got in only once or twice because the person in-charge would ask us to pay extra money for the comfort of travelling in the compartment.

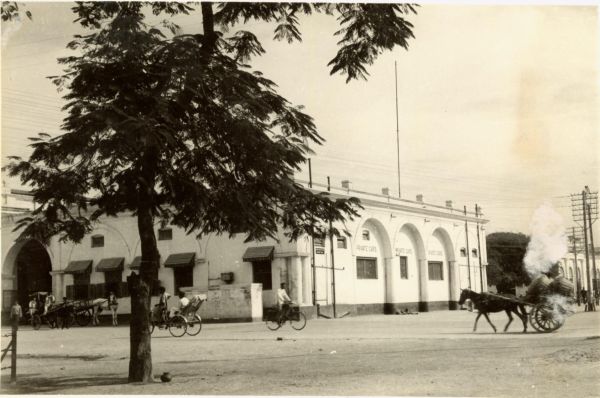

Another such place my father liked to visit was Jhusi, which was also located across Ganga on the metre gauge route from Allahabad towards Varanasi and beyond. The trains for Jhusi used to originate from a different terminal called Allahabad City. As this terminal was located in an area called Rambagh, it was generally known as Rambagh station.

In those days, there was no road bridge on Ganga towards Jhusi. In fair weather, i.e., between December and May, a temporary pontoon bridge was constructed across Ganga. In other months, travel by train or crossing the river by boats provided the link. A very circuitous road link did exist which was less frequently used. Therefore if a return train was missed from Jhusi, coming back to Allahabad used to become a hazardous journey, particularly when there used to be no pontoon bridge.

However, visits to Naini, across river Yamuna, were not as difficult as there were several trains stopping there. The trains to Naini used to cross river Yamuna by a road-cum-rail bridge, which is one the oldest rail bridges in India.

It was common for the third class coaches to be over-crowded and dirty, littered with peanut shells, paper bags, and fruit peels. Vendors selling peanuts, roasted gram, and salted snacks used to frequent the compartments, along with street singers and beggars. There were still many coaches in use that had doors opening outside, instead of inside, as is the norm these days.

On the platforms, particularly at big stations in addition to the name boards of the station, the name of station could also be seen in the form of small bushes planted in the shape of roman letters of the spelling of the name. The platforms used to have water supply through taps with push-cocks. The taps were located at a height of about three to four feet from the platform level. Along with the taps, there used to be a small cemented tub in which lumps of soil were kept for cleaning hands. On the tub, the words Saaf Mitti (clean sand) used to be painted.

During summer months, cool drinking water was made available for passengers, through earthenware pitchers. At small stations, the pitchers were kept at a fixed place and water was given to passengers by the waterman. At bigger stations, the pitchers were also kept on mobile trolleys and water used to be supplied on trains. The watermen were normally called Paani Pande (literally, water priests) as the watermen were normally Brahmins by caste lest lower castes contaminate the drinking water for Hindu passengers. I did not see but I have heard that there used to be separate drinking water arrangements for Hindus and Muslims generally known as Hindu Paani and Muslim Paani.

One of my lasting childhood memories of railways is of a Train Guard at Allahabad station in the 1950s. I had gone to railway station with my father. The Howrah bound Kalka mail arrived on the platform. The guard of the train was standing by the side of his compartment wearing sparkling white uniform, a peaked cap on the head, a cross-belt across the chest, and a whistle dangling on a cord. When the departure time came, he blew the whistle, waved the green flag, and the train started moving. Suddenly, we saw a foreigner lady running to catch the first class compartment. Her husband was standing on the door and shouting "quickly, quickly". However, she could not run as fast as the train was moving.

When the guard saw the lady, he again blew the whistle, started waving the red flag and the train came to a stop. Finally, the lady, who had gone to the bookstall and was delayed there, entered her compartment after profusely thanking the guard. This incident left an impression on my young mind that the guard is most powerful person on railways.

I now wanted to become a guard, when I grew up. A wish which was never fulfilled. I did join the railways years later but in an entirely different capacity.

_______________________________________________________________

© Anoop Krishna Jhingron 2013

Comments

Ice Slabs in Railway Compartments

Add new comment