Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Buddan Sahib and the Mysore Tonga

Category:

Shenoi, a civil engineer and MBA, rose to the rank of Deputy Director-General of Works in the Indian Defence Service of Engineers. He has also been a member of HUDCO’s advisory board and of the planning team for Navi Mumbai. After retirement he has been helping NGOs in employment-oriented training, writing articles related to all aspects of housing, urban settlements, infrastructure, project and facility management and advising several companies on these issues. His email id is mpvshanoi@gmail.com.

Editor's note: This story has two parts. Buddan Sahib is the focus of the first part while the Mysore Tonga is the focus of the second part.

His full name was Ali Hussein Buddan Sahib. But hardly any one knew him by that name\; none of his customers, not even the regulars. To all of them he was Buddan sahib.

In Mysore in the 1940s, he was the owner of a Shah Pasand Tonga (horse carriage -see below for details), which ferried most of us in our mohalla (neighbourhood) to other parts of the town or beyond to near by villages. It was also the pride of the mohalla.

Most of the Tonga owners in Mysore were Muslims. Around the stands, it was common to see clusters of Muslims homes, with mosques and Madarasas (schools) nearby. As his name indicates, Buddan Sahib too was a Muslim.

He took pride in his Tonga and his horse. His horse, named Sikandar (the Indian name for Alexander the Great) was medium height, (tall by the average for Tonga horses) milky white with patches of grey and black in many places with a predominant black spot in the centre of its forehead. It had large expressive eyes, strong sinew legs and a bushy tail.

Sikandar was well fed with green grass and boiled horse gram. Buddan massaged the horse every Friday as religiously as he attended the mosque. So its skin had a pleasing sheen. Whenever there was a break, horse and the owner rested, and Buddan would talk to Sikandar. He would stand near the horse, and murmur gently into his ear the day's happenings, the passenger's behaviour, his joys and sorrows. Sikandar would be eating the gram from the gunny bag tied round his face. When people commented on Buddan's unusual relationship with his horse, he would say Sikandar was his virtual son, as he provided Buddan and his family their roti (bread).

Once in two to three months the horse would need new shoes. It was almost half a day's ritual. The stand where Buddan used to park the vehicle was part of a large maidan, which was mostly dusty, with a few trees like banyan here and there. The maidan served as a place for holding a weekly shandy (farmers' market), a resting and watering place for the bullocks, carts, Tongas, play field for the boys, and other uses. The horseshoe maker would be sitting at his designated place under a tree. The horse would be tied to the tree, and each leg would be securely tied to one of the peg driven into the ground. The shoemaker would then release one of the horse's legs and hold it securely between his own legs. Then, he would remove the old shoe and nails, file and trim the heel and drive in the new shoe.

If a nail hurt the horse, and he tried to kick or shake, Buddan would caress the mane and whisper, "Dario nacho (Do not be afraid)" to the horse and caution the shoe maker "Halloo, Halloo (slow, slow)." After the new shoes were on, he would feed and water the horse, and let Sikandar rest for an hour before resuming work.

Buddan Sahib had two wives. This I learnt from my brother. His first wife was his close relative. Unfortunately, she could not bear him a child. Buddan sahib married again, paying a hefty mehar (bride price). His second wife bore him two boys and two daughters. All the children attended Madarasas, not mainstream schools. The elder daughter was married off to a trader in waste paper. Younger was yet to be married.

Both the sons were a great disappointment for Buddan. Neither showed any liking for running the Tonga. The elder was an apprentice with a garage owner. The younger did odd jobs here and there, was a member of neighbourhood gang and frequently had trouble with police. He also demanded money from Buddan now and then.

I learnt from my brother that Buddan wanted a third wife because his two wives did not get on well. Buddan's theory was that if he had one more wife, he could use two of them to subdue third one and have domestic peace. However, as he did not have the money for one more mehar, this theory was never tested!

Buddan had a special liking for our family. This was because of my father. My father was kind- hearted to a fault. He was a temporary clerk in the sanitary department of the Municipality with a princely monthly salary of Rupees 25 only. In those days, the cost of living was low, and it was enough for our family to lead a frugal life.

My mother used to tell us children that our father did not have any bad or wasteful habits. But his heart would melt when he heard sob stories. He would take out whatever money (money in those days was mainly coins) he had in his pocket and hand it over to the person without verifying the truth. So our family had to make do with skipping meals sometimes ... All this generosity left our family almost penniless when my father died unexpectedly when I was in the eight class.

Buddan was one of those who had time and again got help from my father. After the demise of my father, Buddan would sympathize with our plight, charge us less and occasionally run errands for us.

After I graduated from college in 1955, I left Mysore in search of a job. By that time, Sikandar was well past the middle age. A few auto-rickshaws, may be thirty or so, had made their appearance in Mysore. The municipal bus service had also improved. So Tongas were facing competition.

In 1962, after the Chinese skirmish, I felt I had not gone home for a long time. I was feeling home sick and missing Mysore - including it Tonga ride and meals such as ‘set dosa' (3-4 dosas served with coconut chutney, and potato and onion dish). I sent a letter to my brother that he should send Buddan with his Tonga to the railway station to receive us, and I would like to travel with him in his Tonga.

When my wife, two-year-old son and I alighted from the train in Mysore, we were exhausted, as we had travelled from Simla, with breaks at Kalka, Delhi, Madras and Bangalore. Buddan was there at the platform to receive us, and his very presence was refreshing. Buddan took charge of us and our luggage, fussed over my son, and made us feel wanted and important.

As we came out of the station, he brought the Tonga right at to entrance, ignoring the policemen who said that this was not allowed. I could see that neither Sikandar nor the Tonga was in good shape. The Tonga's roof cover was torn and patched up. But I did not have the heart to say anything. I patted Sikandar who shook his head in recognition and then got in besides Buddan in the front.

Buddan asked me about the war. He asked me how far I was from the battlefield. He warned me to be careful and be as far from the enemy as possible. He told me that he had heard that the Chinese were heartless and cruel. They were yellow, had menacing long narrow eyes, scanty beard, and that they would eat any thing from cockroach to human being. I assured him that I would take note of his sagacious advice.

After his enquiries about my family and me were over, it was my turn to ask him about his life. He said that life was difficult as his income had dwindled due to competition from others, city bus and autos. Sikandar was getting old. Children were unruly, with the younger son still getting into trouble with the police.

On that trip, Buddan became my constant companion with his Tonga whenever we visited our relatives, Chamundi hill and nearby places of interest. When the time came for us to leave Mysore, I presented him with a woollen sweater and a muffler I had brought from Simla. I could see tears in his eyes when we departed and he shouted out that I should care of myself and not indulge in reckless bravery

I met him again four years later when I came back to Mysore from Jammu &\; Kashmir. This time Buddan had grown older and thinner. In fact, he had shrivelled. Sikandar had died of old age, and Buddan had bought a horse that was short, skinny - way inferior to Sikandar. Buddan told me the prices had gone sky high for good horses. The Tonga had become rickety. The roof tarpaulin had patches in many places.

Buddan told that it was no longer remunerative to drive a Tonga. The younger generation of commuters preferred auto-rickshaws or buses. Tongas were mostly used by older people and for carrying unwieldy goods. His first wife had died after prolonged illness and being bedridden for several months. He could not tell me what the illness was. But there was constant pain in the stomach. The hakim (a medical practitioner who practiced Unani system of medicine) did all he could. But "Allah ki marzi (Almighty's wish)," and the inevitable happened.

His younger son had run away, and had been seen by an acquaintance in Bombay. The elder son had separated and gone in his own way. But Buddan no longer cared. In spite of his sorrows, he asked me about my work. When I told him I was in Kashmir, he asked me whether it was true that there was trouble. I agreed with him and told him in brief what the problem was. Trouble was slowly raising its head.

Buddan seemed to have had some inkling. He asked in a naïve way, "If the Kashmiris do not want you there, why do you want to be there? Let them have their place. You come back here." I told him I worked for the Government, and had to follow orders. It was up to the Government to take a decision. He said, "Why don't you tell them? I am told you are a big officer."

I had no heart to tell him that the issue was not that simple. Nor I did I think he would understand if I explained the situation some more. So, I simply grunted in agreement.

Once again, when we were leaving, I tipped him generously. In turn, he presented a packet of sweets to my son who was about six years old then. Amidst tears and "Khuda hafiz (God be with you)" we left.

Around three years later, I learnt from my son that Buddan had died after months of illness. I could not find out of what he had died of.

Buddan and his Tonga had passed on into history - but not from my memory and emotions.

|

Shah Pasand and Jutka Tongas |

In the 1940s and before that, Tongas ruled the roost in Mysore.

I remember my father telling me that in the early 1930s, a private entrepreneur had started a bus service from Mysore to some smaller cities. But the roads were macadam or dirt and bad. Some people were not sure whether bus travel was safe, and bus breakdowns were common. Some orthodox people refused to board a bus because of leather cushions, the fear of rubbing shoulders with people of other castes, etc. The service closed down soon.

A rudimentary city bus service started a few years later but my father did not know who the operator was. He hardly used it. By the 1940s, there were some buses in Mysore but they did not follow a reliable schedule. The seats were hard wooden benches as seats, and getting into and out of a bus was uncomfortable.

So, Tonga remained most popular mode of transport. Every mohalla had a Tonga stand where Tongas were parked. It was generally a ramshackle open structure with a few bays, Mangalore tile/Sheet roof and rough granite floor. It had space for storage of grass at rear end of each bay. Also a trough into which a few bundles of hay were opened and dropped. An iron ring either on the rear wall or floor was used to tie down the horse. A large granite platform at the front sloped to the road, an open drain lead the urine to the lower end and out in to open.

Most of the larger stands had a nearby blacksmith shop, where the black smith fitted iron hooves on to the feet of horses and bullocks. One of these stands was located at one end of a large maidan (field), on major road going towards Kerala, a neighbouring State. Here bullock carts used to arrive regularly from villages carrying men and village produce. The stand had been built by the local Municipal Council. The drainage was usually bad and stagnant pools of urine, cow and horse dung were a common site, with the smell carrying far. But nobody seemed to care!

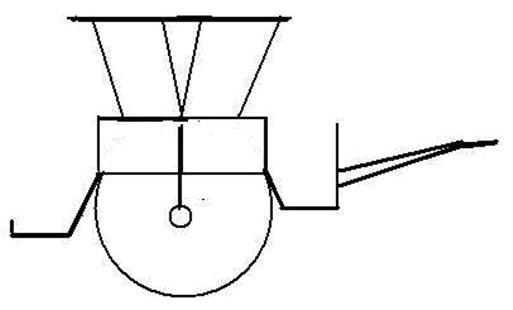

The Mysore city Tonga had a unique design not to be found in any other city or town of erstwhile Mysore state.

Even in Bangalore, the nearest major city, the horse carts were Jutkas, as in all other towns. Jutka is a barrel-like structure with a flat bed supported by two enormous wheels - a design originating from the bullock cart.

It seems that the Mysore Tonga, known as Shah Pasand (royal favourite), was designed at the order of Maharaja of Mysore. The Maharaja had seen a similar design somewhere in the West and liked it. So, he had asked his officers to adapt it to Mysore city's needs. (Editor's note: Tongas of this design were common in other Indian cities, and some were in use even in 2008.)

Those of us who were used to travel in the Mysore Tonga did not like the Jutka design. I think you will agree with me after reading my description of the difference in design and the resulting ride quality.

The seating portion of the floor of Tonga was rectangular in section made of wood. On the two sides, the lower half was made of planks and the upper half was made of canvas, covering a skeleton of steel angle frame. This frame was fixed to lower plank half by fan shaped steel frame. The width of the seating part of the floor was about 5 ft and length 4 ft. The wood scantling floor was covered a leather cushion stuffed with coconut fibre. There was a cross board with cushion cover about 10 to 12 inch high which divided the length in to two equal half.

Two passengers could sit at the back facing the rear. The driver and one more passenger sat at the front facing forward. This rectangle had an attachment - shaped like a reverse L - attached to the bottom of the rectangular portion to allow the rear passengers to let down their legs comfortably. At the front, an open U like part made of scantlings was attached to the seat, and this let allowed the passenger and the driver to let down their legs comfortably. It also served to store grass for the horse.

Both of the front and rear end portions could also carry small luggage trunks in them.

At the forward end of this U, a 10-inch board was fixed, which acted as a shield between the men and the animal. This entire upper portion was supported by a beam with arched plate springs on each side. These springs, in turn, were supported by an axle that rested on a spoked wheel one on each side. These wheels were similar to those found on bullock carts but were larger in diameter, lighter, and had fixed rubber pads all around. A yoke fixed to this carriage rested on the shoulder of a saddled horse. The leather reins worn round the face of the animal were held by the driver. The double springs provided good riding quality. This open structure provided each person an all-round view, breeze and reasonable leg space.

The Jutka had evolved from the traditional bullock cart. Its barrel shape and narrower width allowed only a single passenger in the back. The driver occupied the leading end. All others had to huddle inside, along with the luggage\; people sat cross-legged around or on it. Grass was spread over the floor over which a dirty bed sheet or tarpaulin was spread. The inside space was mostly for the children or ladies.

When the Jutka was on the move on the road, the driver would frequently request the occupants move up or down to adjust the load on the horse as it moved up or down an incline. If the horse or the driver had a bad stomach, which was common, the malodorous wind of farting rushed into the interior as the barrel acted like a tunnel!

During the rains, a Jutka gave more protection than a Mysore Tonga. Still, we Mysoreans preferred our Tonga any day!

Jutkas in 2008

In 2008, I got a glimpse of the grim future Jutkas and their owners face in Bangalore.

I found that many of the Jutka stands of the olden days have been converted into auto or taxi stands. I went looking for Jutkas in Sheshadripuram (an older suburb), Russell Market (one of Bangalore's oldest markets) and other similar places, but I did not find either a Jutka or a Shah Pasand Tonga.

Then I went to the outskirts of Bangalore to a gaothan slum (a village, now swallowed by the spreading city but not otherwise developed). At a stand, I found three horses, of which one was just bones and skeleton. There were two Jutkas, of which one was old and dilapidated, while the other one was colourful and sturdy. Three families lived in the stand along with animals. A public tap and open area for morning ablutions completed the dismal picture.

Better planning of the inner area of the city, with reservations for Tongas, Jutkas and bicycles would have perhaps given these non-polluting modes a greater chance to survive.

© M P V Shenoi 2008

Comments

Add new comment