Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Growing up in Princely Mysore -2

Category:

Tags:

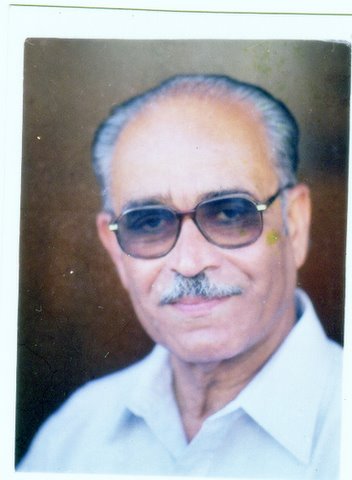

Bapu Satyanarayana, born 1932 in Bangalore, retired as Chief Engineer, Ministry of Surface Transport. At present, he is the presiding arbitrator of the Dispute Adjudication Board appointed by the National Highway Authority of India. He lives in Mysore, and enjoys writing for various newspapers and magazines on a variety of subjects, including political and civic issues.

Editor's note: This is the second story about the author's life. The first story is available here.

Forbidden drink

Coffee was a taboo in our house for youngsters. I do not know what exactly the reason was for it.

Probably it was considered as a bad habit. When something is prohibited, it often raises curiosity. It was no different in this case. Therefore, we wanted to taste it. But father was dead against this, and instructed ladies of the house not to indulge us in this.

When an instruction came from my father, it was considered as an order that had to be obeyed. But we would plead with our mother and aunt, and I remember one incident in our house in Mysore. (This house was located on Weavers lane in Krishnamurthy Puram. The house, which our family sold later, still exists adjacent to the house of D V Krishna Murthy, a famous publisher.)

I believe my uncle Bapu Krishna Murthy, who is seven years older than me, and I climbed the high plinth and perched on the window sill precariously with the support of the bars of the window that overlooked the dining hall. We shouted to draw the attention of my mother, and aunt Narasamma. We stretched out our hands through the bars like monkeys in a cage pleading with them to give us coffee. Since father was not in the house they relented and gave us coffee.

We were about to sip the forbidden drink when, I do not know how, suddenly my father came into the house and caught us in the act. He snatched the steel tumbler, and threw it away. Next thing I know is I was dragged into the house and soundly thrashed! When my father beats child, it was like third degree punishment, for he was unsparing.

Of course, we found ingenious ways to counter this prohibition. In the garden behind the house, we had built a small cubicle, wherein we had secretly kept coffee powder and sugar and other things along with a metal stove for burning charcoal. In those days, elders would sometimes go to the cinema, leaving children in the house. It was fun time for us. As soon as they left, my uncle and I would repair to the cubicle, start preparing coffee, and enjoy to the fill. It is a contrast now, for if a youngster does not drink coffee, we tease saying what fun they are missing.

Everything in place

The family did not normally eat lunch together as : children would have gone to school and father to his place of work. It was only during night time that all the members of the family would take food together. There was no dining table. All of us sat on the floor on a small low wooden seat. Silver plates or banana leaf would be placed before us\; stainless steel plates came later. Usually dry curry of vegetables (Palya), or liquid curry normally a little hot to taste (Gojju), or Green or Bengal gram soaked in water to make it soft and garnished with salt, coconut shavings, green chilies and lemon (Kosumbari in Kannada - an excellent supplement as protein), and invariably either lemon or mango pickle would be served along the outer border of the plate.

Every item served had its allotted place on the plate. In the beginning, salt would be served on the left hand corner of the plate on the floor, may be it was considered untouchable! The pickle was served on the left hand side. If it were a special occasion, a sweet dish would be prepared (Payasa), which was served at right hand bottom corner. Then rice would be served and the lst one was a spoon of ghee.

It was the practice tha no one started eating the food until ghee was served on the cooked rice. As always, father, the head of the family, would give the lead, casting an imperious look on us children sitting to his left. That was a signal to start eating. Father or any person whose thread ceremony had been performed would do Parishanchane. In this ritual, the person would take water in the palm of his right hand, and slowly sprinkle it in a continuous line all around the plate, Then he would place five small pinches of rice to the accompaniment of a recital in which the deities (Pancha Bhoothas)were remembered. Then, he would join them into a small heap and pour water. Then, holding the plate in his left hand, he would take a small amount of water in his palm and drink before starting to eat. In fact, before eating he would take a small pinch of rice on which ghee was poured and taste it.

A learned Pandit may explain the significance of the exact significance of Parishanchane. I guess it may have been an effort to keep ants from climbing into the plate may be an additional reason. In earlier times, only banana leaf was used as a plate, and probably the rice acted as food for them! I guess all this was meant to be a ritual to inculcate discipline, stressing that it starts in every act.

If Payasa was served, we had to start with it first. Otherwise, the choice was yours: start eating, taking any dish you like. Normally there used to be three courses. One was Saaru, a thin lentil-based liquid preparation, using several condiments. Another was Huli (sambar), a little thicker liquid preparation with vegetables, and the last would be curd and rice. Taken together, it was a wholesome meal, and acknowledged by world surveys as good healthy one.

Mother would serve us and would eat later. Mother would eat in the same plate as my father's, without cleaning it. I do not remember my mother taking food prior to my father.

Ky-thutthu

We children would often plead with mother to give food through ky (hand) thutthu (morsel of food) instead of eating from the plate. In this style, there would be no plates. Mother would plant herself in the middle and sit on her haunches. All the children sat around her in the same style. She would have mixed Saaru with rice thoroughly in a vessel with such a consistency that it could be made into a lump in her hand. Turning it a few times to make it into a round shape, she would drop it into our outstretched hands.

She would pivot around on her feet and give everyone, in turn, a morsel of food. She would repeat it with other courses till we were all well fed, with the last course being curd rice. We would all enjoy it thoroughly because with mother serving it so lovingly, the food used to taste divine. At the end, all of us would crave for the last morsel when she scoured the bottom of the vessel for the remaining food. There would be clamour to have it. Normally, the youngest would get it and it would be eaten triumphantly. Usually, the last morsel would be a little watery. It was called Balbajji Bhagya, meaning the one who got it would be lucky and fortunate. It was a lot of fun for us.

Kaamana Habba (Festival)

We observed the festival of Holi in a different manner from the celebrations in north India. It used be called festival of God of love (Kaamana Habba in Kannada). There would be a bonfire of the God of Love (kaama) during the full moon night in a big field (maidan) where men, women and children would gather in a festive mood. To the cries of delight, we all would dance around the bonfire. Jaggery mixed with puffed rice (puri in Kannada) would be distributed to all. It was a grand sight to see the fire leaping into the sky and sparks flying all around when frequently stoked

During the day, bands of youngsters would roam all the streets, singing a hilarious Kannada ditty full of levity, which runs like this:

Kaamana kattige

(Kaama's wood piece)

Bheemas berani

(dried cow dung cake named Bheema)

Adike gotu,

(Dried rounded areca nut)

Ekkadadetu

(Beating with slippers)

Kaamana makkalu

The children of God of love (Kaama)

Kalla sule makkalu

(Those bastard children)

Enenu kaddar?

(What did they steal?)

Soude-Berni kaddaru

(They stole fire wood and dried dung of cattle)

Ethakke kaddar

(Why did they steal?)

Kaamanna sudukke kaddaru

(To burn God of love-Kaama)

At the end of the song they would all shout with palms slapping against their mouths.

The real fun for children started during daytime. They would go to every house and ask for firewood. Normally, the householder would give some firewood, or even old damaged chairs etc. If anybody were unwilling to give, the intrepid boys amongst us would scale the high compound stealthily, and steal whatever which was fit for burning, like dried fronds of coconut tree etc. Sometimes, the irate man of the house would chase them out. It was all in good fun.

In the evening, all the firewood collected would be stacked in a pyramid shape. After doing the pooja, the firewood would set on fire to the beating of drums or plates, to the wild cheer of all. Presumably, this burning of Kaama was symbolic of dousing the wild and forbidden desires in people.

The games of those times

When I was in middle school, high school and even in college, we spent more time playing rather than studying, unlike now. It would be unfair to blame the students now, for the whole game of learning is different with accent on competition leaving very little time to devote for play. Almost all the time, we would all be playing either in the streets, in the playground or in big fields with lot of trees near our houses.

The types of games we played then have practically disappeared now. The favourite games for children were Mara kothi (Tree Monkey) Chinni Dandu (Gilli Danda in North India), Buguri (spinning the top.) Mara kothi game can be played by many people. This game was a test of agility to climb on the tree and escape being caught by the one who is made to run and pick up stick thrown, while we all scamper like monkeys climbing on branches. It is the boy's business to keep an eye on the stick and try to climb the tree to catch before somebody climbs down and getting hold of the stick and throws far away and climb again. This goes till somebody is caught in the act of throwing.

The game of Gilli-Danda is well known throughout India. It may be called as cricket, local style. (Aamir Khan is shown playing it in the film Lagaan.) It was so popular that we used to have inter-college competition. One such was arranged by Sri Nanjunda Swamy, Department of Statistics in Saradavilasa College. (Many famous people, including Sri N.R. Narayana Murthy, the founder of Infosys have studied here.)

Buguri required the skill of spinning a top so that it strikes anther top lying on the ground. The spinning top would be taken to the hand, and the top lying on the ground would be pushed. This would be played on the street, dragging the top all over the place from one street to other .The top would have a sharp nail. Holding the top in the hand, the loser's top would be struck with increasingly successive blows (Gunna in Kannada). The final object was to split open the loser's top. These simple games gave us immense enjoyment.

Buguri required the skill of spinning a top so that it strikes anther top lying on the ground. The spinning top would be taken to the hand, and the top lying on the ground would be pushed. This would be played on the street, dragging the top all over the place from one street to other .The top would have a sharp nail. Holding the top in the hand, the loser's top would be struck with increasingly successive blows (Gunna in Kannada). The final object was to split open the loser's top. These simple games gave us immense enjoyment.

Vaaraanna

My family used to provide meals to several students in our house. We followed Vaaraanna, the concept of providing meals for poor students. A poor student's need for food would be met by meals provided in seven different homes in a week\; or a particular home could have meals for more than a day in a particular home. The students were treated with utmost courtesy as a part of our family, and they felt comfortable because there was no sentiment of charity attached to the gesture. In fact, it was so natural that we would even send them on small errands, as we would do with our own children. This strengthened the bonding as a member of our extended family and an honoured guest. There were several instances when the lady of the house would provide the student a better fare than for her own children. This was the concept of hospitality prevailing at that time. In fact, students who have followed Varaanna have later attained great positions in life.

Simple joys

The type of excitement and enjoyment that as children derived in simple things is such a contrast to present day living when children play video games, use mobiles, and many other modern toys. For example, as children we would use a magnifying glass (Bootha Kannandi in Kannada) to direct the sun's rays to a point on a sheet of paper to see it burn a hole or stack of dry grass into a small heap and see it go-up in fire . Or, we would play with magnet to see how the iron filings would get attracted towards the two ends. Or, we used what we called a pin hole camera Editor's note: kaleidoscope) in which we would see different patterns of broken bangles when it was shaken. Sometimes, we would get strips of discarded cinema films, and project them on the wall or a screen using sunlight and magnifying glass to see the blown up figures.

In those days, every house was a veritable small theatre. Children would convert one end of the hall into a stage using any cloth like saris or bed sheets etc slung across a string to make a curtain. The children would stage historical dramas attired with suitable dress and crown, holding mace or sword made from cardboard. For elders, casino

it was great fun and pride to see their children delivering dialogue with gusto. In case the children forgot the lines, the elders would prompt them from the side. The audience were mostly children from the neighbourhood. Now, with the passage of time, it seems like the scenes from another world.

Padi bedodu (Begging for alms)

During the month of Shravan, on every Saturday, boys would be given a brass vessel to hold in both hands to visit few houses in the neighbourhood. The attire was simple - wrapped up in a dhoti, with a bare chest covered with a cloth in the style of a priest who comes for doing pooja or any ceremony in the house. The face was scrubbed clean with forehead sporting three prominent vertical lines to represent the religious mark of a Vaishnava.

We would be asked to visit a few houses known to us in the locality and loudly chant in front of their houses "Venkateshwara mangalam," that is, invoking the name of the lord Venkateshwara in a typical fashion of a mendicant. Before we left the house mother would pour rice into the vessel in the pooja room. The lady of the house would open the door and offer rice pouring it into the vessel. She would be aware that children would visit on such days as a ritual. Since we are known to them, we would be received with great love and affection. In this way, we would visit a few houses and with vessel filled up to the brim would return home. The rice would be cooked and it would normally be used to prepare a sweet pudding and we would all partake in it with relish.

We all took to this ritual naturally, without any hesitation or entertaining feeling of reluctance as though going for seeking of alms was demeaning. Probably, this was a foundation preparing our minds for the fourth stage of life. According to Hindu belief, the life of man is divided into four stages, viz. Bramhacharya, Grihastashrama, Vanaprasthashrama and the fourth stage is Sanyashrama. During the fourth stage, we are expected to subsist mainly on alms. I presume this was the basic object to instil in us the idea that there is nothing degrading in begging for alms.

© Bapu Satyanarayana 20012

Comments

Add new comment