Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Walking in the hills and the plains of the Punjab - in the times of the British Raj

Category:

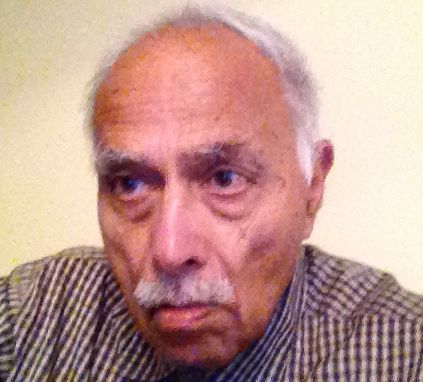

Dr. Anand - an unholy person born in 1932 in the holy town of Nankana Sahib, central Punjab. A lawyer father, a doctor mother. Peripatetic childhood - almost gypsy style. Many schools. Many friends, ranging from a cobbler's son (poorly shod as the proverb goes) to a judge's son. MB From Glancy (now Government) Medical College Amritsar, 1958. Comet 4 to Heathrow, 1960.

Long retired. Widower. A son and a daughter, their spouses, five grandchildren, two hens (impartially, one black, one white) keeping an eye on me as I stand still and the world goes by.

My father was fond of walking. Hiking is too formal an activity. He preferred to walk.

And see the surroundings, the topography, the trees and shrubs. Hear the birds sing. At night, there were the silent owls swooping down to pick up a field mouse. Plenty of bats. Listen to the howling of the jackals. (I wonder if there are any jackals left in India?)

And then there were the dogs. Mostly pariahs. Some would attach themselves to a village or a residential locality and charge any strangers.

These dogs were the source of much anxiety for my father. He was in the habit of carrying an umbrella - in summer to shield himself from the sun, in the Monsoon to ward off the rain, at all times to ward off the dogs, which were rather plentiful in the India of the past. In truth, although Gow Maata (Mother Cow) would often lie on the road oblivious to the tonga - the two-wheel carriage pulled by a single horse - the bullock cart, the occasional cyclist, the rare lorry, the dog was as much of a nuisance. Possibly the dogs regarded my father's umbrella as a possible weapon of assault, and therefore, my father as The Enemy. But once a year or once every two years, a Dog would manage to nip my father's ankle. In those days, rabies (hydrophobia) was not uncommon in dogs. It was easily transmitted by dog-bite. The only prophylaxis was anti-rabies vaccine injections. The vaccine was not available even in the provincial capital (Lahore). You had to go to the Pasteur Institute in Kasauli, Simla Hills. Thus, it was that my father developed a taste for the hills, and walking in the hills.

I was a beneficiary of my father's taste for "observant walking". Whenever we went walking, I would get a running commentary on the geography, the geology, the botany, the zoology. Since these walks were joyful (including picking wild strawberries growing on the hillside, drinking spring water spouting from mountain side, pulling a ripe wild pear with the hook of the umbrella) the education was painless. Long lasting memories without the obscenity of examinations.

As my father was a lawyer, his holidays for a sustained spell of hill walking were perforce limited. As my mother was a doctor in government service, her holidays had to be sanctioned by the Civil Surgeon of the district (Zillah). All this limited the opportunities. Still, we managed about ten days holidays in the hills most years of my childhood.

An early memory is of Sri Nagar, (J&\;K, not Kumaon),

It would have been the summer of 1936 - my sister had not been born. I was riding a small and gentle pony led by her Kashmiri master. My little brother, about two years old, was carried sometimes by a labourer (coolie was the term in those days, now consigned to the dustbin of obsolescence and not politically correct) and sometimes by my grandmother. My grandmother seemed to have always deserted her hearth, left my grandfather to cope with the help of his nieces, and come to our aid.

So we went up the hill. I remember it was a hot day. At the top was a small temple. Later I learned that it was the temple of Shankaracharya. At that time, the temple left me underwhelmed.

When the Second World War broke out, we were in the hills. I think it was Murree (always described in Urdu and Punjabi, as Koh Murree. Koh is the Urdu and Punjabi word, and also I believe Farsi, for mountain).

We were walking along a road on the outskirts of the town when we chanced to meet one of my father's distant cousins. He was from Lahore, the capital of the Punjab. Feeling certain that Lahore would be bombed by Germany, he was considering selling up and moving to the hills. As the events panned out, German planes did not reach anywhere near Lahore. However, seven or eight years later, arson, dagger, and gunshot drove half the population of Lahore out.

I was impressed by the large size of the myriads of snails by the road side and also crossing the road. I had heard that snails were a delicacy

In France, for some reason, there was no effort by the locals, or the visitors, to collect the snails for the kitchen.

The hill stations were remarkably free of stray dogs. Presumably the Brits, civilian and military, arranged to keep the strays away, one way or another, from fraternising with their pedigree pets.

Sometime in the 1930s, we visited Abbottabad in the hills straddling Punjab and the North West Frontier Province. An old class-mate of my mother lived there with her husband. We wandered around their garden, but did not see the town.

In 1942, we spent a couple of months in Solan, a "native state" ruled by a Hindu raja.

It was the time of cholera outbreak in the villages. From our holiday apartment, looking down in the Khud, every day you saw a funeral procession to the cremation ground. After a few days, we made any possible excuse to walk away, down the road to the small town. It was not a great sight either. But no depressing sights.

Looking back - strange that in the plains we always came across people with the begging bowls. But not in the hills.

The writ of the Raja ran on a very small area around the town. He had no army, being under the protection of His Britannic Majesty. There were very few policemen, recruited from the locals. Even to me, a small child, the policemen looked ridiculously small and weak. Perhaps they were not weak. The physique of the hill men was on the small side - smaller than the Gurkhas. Considering how they ran up hill and down, carrying loads, they must have been fairly strong.

The terrace farms grew maize (Indian corn). In those days, there were plenty of Himalayan bears there. The farmers did not mind a wayfarer, feeling hungry, snapping off a chhullee or two. However, the marauding bears were a different matter. Armed with a stick only, the farmer was no match for the bear.

A bear in the field, we were told, would regard any human around as a trespasser and attack to kill. We, therefore, kept a wary eye open for bears. Fortunately, we did not encounter any.

There were, in the hills around, plenty of walnuts and wild pears -free for the plucking. This we did, using the hook of the umbrella.

Close by was the long narrow gauge railway tunnel of Barog. It was, perhaps, the longest tunnel at that time in India. The tunnel had recesses at frequent intervals. When you were walking through the tunnel, the hooting of an engine allowed you enough time to jump in to one of the recesses. The smoke (these were steam trains) did sometimes make your eyes water.

Besides the ordinary trains for us lesser mortals, there were the rail cars for rich folk of the upper classes - some were business men, other were British officers (military) and officials (civil). Then the Governor of the Punjab, the Viceroy of India, the Commander in Chief in India, travelled with their families by a rail car - separate cars for each of the dignitaries.

Close by were the hill forests where the Maharaja of Patiala ruled - and hunted. There were cheetahs, leopards, and tigers. The locals warned us against venturing in to those pine forests. However, my father took no notice, and we would go walking and picnicking. We saw no carnivores. Nor even a deer. Once or twice, we heard gunshot somewhere, echoing in the hills. But never a glimpse of the hunted nor of the hunter.

These pine trees dropped their cones - ripe for us seekers-of-free-food to take out the pine nuts. Whether these trees were the source of the pine nuts sold in the shops, I do not know. But they tasted the same.

There were in these hills (rather mountains) numerous springs for us to drink water from. And nearby would always be small but very sweet strawberries - free for the taking.

I had never eaten strawberries in the plains but had eaten strawberry jam.

______________________________________

© Joginder Anand 2015

Comments

Add new comment