Rehabilitation in Ludhiana (Part 3) by Anand Sarup

Category:

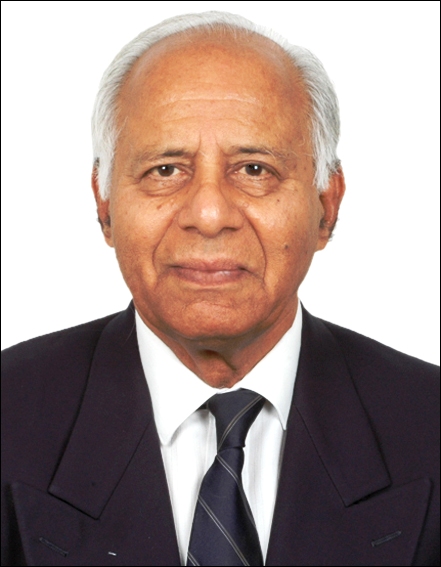

Born in Lahore on 5th January, 1930, to Savitri Devi and Shanti Sarup and brought up in an open environment, without any mental conditioning by a denominational commitment. He imbibed a deep commitment to democracy and freedom because his family participated actively in the freedom struggle. In 1947, together with his family, he went through the trauma of losing all, and then participating in rebuilding a new status and identity. He Joined the IAS in 1954 and retired in 1988 as Education Secretary, Government of India. Later, he became Chairman, National Book Trust. Also co-authored, with Sulabha Brahme, Planning for the Millions.

Editor’s note: This is Part 3 of a three-part story. Part 1 describes the family’s decision to leave Pakistan, and Part 2 deals with the family’s move to India.

After being driven out of Pakistan in September 1947, by February 1948, we had settled into some kind of a routine in an ill-equipped house on Hazoori Road, Ludhiana.

Life in our ill equipped house on Hazoori Road wasn't altogether dull. Even in financially difficult times, we found ways to liven up our existence. I had made many friends who were willing to ignore our lack of resources. We could and we did invite our friends to join us for a meal and we could always persuade our mother to liven it up with her delectable Kheer - an Indian rice pudding, immensely tastier than the dull western version.

The younger children of the family were always into some adventure or the other. If there was a murder nearby, two of my sisters would go trailing the police to watch what was happening. The girls enjoyed unquestioned access into the neighbours' houses. They would take a short cut through some people's homes on their way to and from their school.

There was a fellow who made delectable Chhole (cooked gram), which he, dressed in spotless and immaculately ironed kurta-pyjama, brought out on his handcart only at four o'clock in the afternoon. His wares were so popular that he was often sold out by six o'clock. My youngest sisters frequently went to his house to watch him make his Chhole.

Something was always happening in the neighbourhood. Whenever the Free Style wrestlers, King Kong, Zabisco and others came to town, they went around in Tongas (horse drawn two wheelers), followed by a crowd of urchins. It was a sight to see the wrestlers bend down with their feet well apart to glue up the posters about their fights and paste these on the walls. Those days, new movies were announced by pasting posters on two wheeler push carts, which were taken around the town. The processions taken out before Dussehra were always a big draw. The whole town went to see the burning of Ravana's effigy in the Daresi grounds.

All my four sisters sat in every session of tea and parathas with my friends, irrespective of how old they were and what their position in society was. In the process, my sisters they acquired a fair knowledge of the socio-political issues we discussed day in and day out. They also absorbed a lot of poetry of Mirza Ghalib, Iqbal, Faiz, Sahir and many others, which surprises people even today.

Once Aruna Asif Ali,a communist fellow traveller (who was later honoured by the President of India with Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award), was hidden from police by my communist friends in our house. I wasn't there and cannot imagine how she managed to stay for the whole day at our house, sans a water closet and sanitary facilities. Anyway, my youngest sister Aruna could not help barging in to see her. When Mrs. Asif Ali casually asked her as to what was her name, she promptly blurted out that her name too was Aruna Asif Ali. On hearing this, everybody broke into irrepressible guffaws of laughter!

Those days, every political meeting was announced by taking the main speaker (except, of course, national figures like Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu or Jai Prakash Narain) around the town. I distinctly recollect Master Tara Singh, a famous leader of the Akali Party, being taken in an open truck through the street along our house. Those days he was fighting for the control of all the Gurudwaras and incidentally, all of Ludhiana's mosques had been converted into, and still are functioning as Gurudwaras. I also recall how the bloated dead body of a naked woman lay very near our house on the main thoroughfare for a whole day. In a sense, we were a part of whatever was happening outside\; we had only to open the door and be a part of it. It was fascinating seeing the flow of life from such close quarters.

Obviously, we could not be satisfied with such a static situation. As a family we wanted my father to return to his normal middle class life, without having to hide the scars of the daily struggle for survival.

We got an opportunity to achieve this when the Punjab Government announced that those who had lost workshops in the Pakistan would be allowed to bid for workshops Muslim entrepreneurs had left behind. While this was generally welcomed, being a government offer, it inevitably had a fly in the ointment. The would be bidders were informed that they would not be allowed to see what was inside the workshops. All the efforts to get a modification of this absurd order failed because the government took the specious plea that the bidders were being allowed to bid without verifying what was inside their old workshops in Pakistan. The plea that this was going to be competitive bidding, and not an allotment against the claims made by the refugees, was dismissed summarily.

At this stage, one of my friends from the civil service went out of the way to help us. He too had reservations about the view taken by the government: he allowed my father and some of his friends to see the insides of the units being put up for bids. Though my father had no money to make any bids, this move gave him a big advantage over the other bidders who were going to make blind bids for the workshops on offer. When one of his old Lahore acquaintances learnt about my father's knowledge, he decided to join hands with him and put down his money to enable my father to make the bids.

When the bidding started, the other bidders started seeing a pattern in my father's bids. They quickly formed a committee which decided that they would accept his judgement and, for a token cut for him, let him decide the price at which they would purchase the properties. That evening, when the bids closed, my father's share of the profits thus earned, totalled to a princely sum of twenty thousand rupees. We were thrilled beyond words and did not bother even to think about the large profit made by his partner. We returned home having acquired a workshop and also loaded with sweets and gifts for everyone!

After this, several things happened in quick succession. I got the permission to get my Intermediate degree (F. Sc) by doing some social service. This ‘social service' was supposed to be approved by the Punjab University but its ‘approval' was no more than an eye wash. The University was in the process of being re-established. It just had no resources either for processing thousands of requests or for evaluating what had been done by the volunteers. Therefore, the whole process was delegated to the District Relief &\; Rehabilitation Officer, who in turn depended upon the Ward Chairman of the Congress to certify whether a volunteer had done something worthwhile by way of social service.

This so-called Social Service could range from writing house numbers on the outside of the houses left over by the Muslim migrants to filling up some forms for petitioning the authorities for relief for refugees. Filling up forms and writing house numbers were the most popular type of social service. When I told my father about this, he did not approve of making a mockery of social service by this tokenism. He suggested that I could do some meaningful social service by going to the refugee camp in which Muslims were waiting for migration to Pakistan. These people could be in need of a medicine or milk for a baby or for someone to write a letter for them. He knew from personal experience the hundred things they could not do because of their inability to venture out of the boundary of the Refugee Camp.

This appealed to me and my friends Madan Lal Didi, Har Krishan Lal and Iqbal Krishan. They decided to perform social service in the Muslim refugee camp, though they had no need to do so because they had already got their college degrees through regular examinations. Nonetheless, we went to work in the Muslim refugee camp everyday and came back feeling satisfied that we had performed some good and necessary service.

One day, we unexpectedly ran into the poet Sahir Ludhianvi's mother, who had refused to abandon her house when Sahir and other Muslim families had left for Pakistan. She was now in the refugee camp. Har Krishan and Madan Didi knew her very well because, as Sahir's friends, they had enjoyed her hospitality almost every day. I too was a great admirer of Sahir's poetry and knew his Talkhiyan by heart.

None of us was willing to let her stay on in the refugee camp. We moved her back into her own house close to the Jagraon Bridge. We also arranged for all the provisions for her and also found a giant tin of egg powder. We visited her every day to inquire about her welfare, recite Sahir's poetry, talk about the inequities of the partition and eat her delicious parathas with large helpings of omelettes made from the egg powder.

After a while we learnt that Sahir had come back and was living in Bombay. Seeing what was happening to Non-Muslims, he had refused to take a pledge of allegiance to Pakistan. Naturally, his mother too left for Bombay to join up with her son.

The three months of social service passed very quickly. Now I was finally ready for admission to the undergraduate programme. Because I was also one of the bread winners of the household, I had no choice but to continue to live in Ludhiana, and study the subjects that were available in Ludhiana itself. Because of my interest in Political Science and Economics, I took these up. Even before the classes started, I read up all the texts prescribed for these subjects. The story this time was going to be different from my earlier failures in Lahore!

Another event of some significance to us was the release of a shop premises in the midst of the engineering goods market. My uncle, who lived in Ludhiana, had hired this a few months before the Partition to meet an unforeseen eventuality. With the money my father had earned through the auction of workshops, we were able to start a shop selling some tool steel (Tungsten Steel), molybdenum tool bits, and Carbide tipped tools my father had brought over from Lahore.

Selling these wares was a problem. This was chiefly because Ludhiana's industries were way behind the industries in Lahore, even though bicycle parts and old fashioned machine tools were manufactured in and around Ludhiana. We soon realised that we could not sell our goods sitting in our shop. However, we could market these in industrial establishments in Phagwara, Gobindgarh, Khanna, and Laandhran provided we took our products to their doorsteps and demonstrated their effectiveness on the client's machines.

This was quite a challenging task. In spite of being a student, I travelled as an itinerant salesman, three or four days a week. I demonstrated the effectiveness of our tools on the spot to technicians who usually started with a lot of misgivings but frequently ended up quite convinced. I would leave home at around eight thirty in the morning and return by two thirty in the afternoon. I didn't have to worry about being marked absent in my class because, my teachers, on learning about my problem, assured me that even if I came to their classes only once a week, they would mark me present for every day of the week.

We had another piece of good luck that enabled us to project our shop as the source of quality precision tools. We received a consignment of high quality small and cutting tools from M/s Alfred Herbert (P) Ltd, Coventry, against an order for which we had made advance payment when we placed our order in Lahore. This consignment brought us, inter alia, a Magnetic Chuck, Micrometers, Carbide Tipped tool bits and Depth and Surface Gauges.

Around this time, my father went into the making of Hosiery Knitting Machines, Four Foot Lathes and other fast moving items in the workshop he had acquired during the bidding described earlier. My father decided that while he would run the manufacturing business, I would mind the shop, selling a range of electroplating materials, small tools of various descriptions, mild steel sections and other miscellaneous items.

Just when we started feeling comfortable, our world came down like a house of cards.

Our feeling of security vanished with two events that took place almost simultaneously. First, the Indian government decided to allow free import of hosiery machines from Japan, which ended the demand for the indigenous machines we were making. We had a sizeable stock of fully finished machines and also many machines at various stages of manufacture. Suddenly, nobody wanted our machines. For a long while, like Mr. Micawber, we kept thinking that something would turn up to bail us out\; finally nothing could be sold even as scrap. This stuff kept lying with us, initially in the workshop and later in the garage of our newly built house for nearly thirty years.

The second shock was the result of the cussedness of the government. This happened even before the collapse of the manufacture of various kinds of hosiery machines. To make our machines, we used to apply for the allotment of iron and steel from the Iron &\; Steel Controller. In spite of our persistent complaints, we seldom got what we had applied for. This meant that we sold these ‘officially' supplied items in the open market and bought what we needed, at market rates, from others who too had got items they did not need.

Strictly speaking, this amounted to buying and selling steel in the ‘black market'. We regularly wrote to the Iron &\; Steel controller, pointing out our problem and stating that, in effect, the government itself was forcing us to commit a serious offence. We never got a reply. In frustration, we approached government officers as well as the Ministers concerned in person, but this too was of no avail. This, after the mess experienced about the bidding for workshops, was another experience of the inherent pigheadedness of government. It taught me a lesson that I never forgot in all my years as a government officer.

One day in 1949, all of a sudden, the police turned up at our doorstep and took my father away for having black marketed controlled iron and steel items. I was also hauled up for this ‘offence'. I had to obtain a bail order on the day I was to appear for my B.A. (Honours) examination. Luckily, the magistrate was a reasonable person who took up my case first and granted the bail immediately. Even so, I was an hour late for my examination. In spite of this, I got the second position in the University: I always keep wondering if I would have come first if I had not been held up for an hour in the courts.

Whatever losses we had suffered because of government changing its policy to allow the import of hosiery machines were soon forgotten. We were far more worried, for a year and a half, over the possibility of our being convicted and sentenced to a term in jail. During this period, we had to sort out the affairs of the workshop, deal with the criminal case and also run the shop.

While going through these experiences, I joined the Government College for doing an M.A in English Literature. I would have liked to study for a postgraduate degree in Economics, given the fact that I had come second in the University in the B.A. (Honours) examination. However, under the circumstances, I could not dream either of leaving Ludhiana to study for M.A. in Economics or walk out of running the shop. Therefore, I joined the only post-graduate course, in English literature, available to me in Ludhiana.

In spite of these problems, I did pretty well during my postgraduate studies. In those days, the teachers dictated class notes on subjects included in the course of studies. This left no time for discussions or interaction. I protested that this was ridiculous because we were studying for the postgraduate programme and should be encouraged to read everything by ourselves. I felt it would be better if the students were given a list of recommended reading, allowed the time to read, and the time in the classroom was used for discussions.

I was able to hold up the process of the dictation of notes for a month. Eventually, I was overruled by the majority of the students who wanted to play safe and follow the time worn practice of taking down notes and memorising these for the examinations. On the urging of my classmates, our teachers gave me the freedom to come to the class only when I wanted to, without the fear of falling short of attendance.

This left me free to attend to our shop, take part in extracurricular activities, sit and work in the library, fall in and out of platonic love, read, write and recite poetry, study current affairs, take part in debates and declamations in Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi and English and to top it all, play the role of Jacques, the melancholy philosopher, in Shakespeare's As You Like It. I still recall that whenever I went up the rostrum to take part in a debate or declamation, my arrival was greeted with the burst of cheers.

For several years following partition, Government College, Ludhiana was an unusual institution. This was because the college had attracted non-Muslim teachers and students from the best institutions in Pakistan. These included the Government College and Forman Christian College, Lahore, and Gordon Colleges in Multan and Rawalpindi. As a result there was a highly competitive environment for studies in Government College Ludhiana. A substantial number of its students were able, every year, to get into the IAS, the IPS and the Central services. In 1954, besides me, four others who had studied in Government College Ludhiana, in a batch of thirty one originally selected for the IAS.

Though I did very well in the college and managed the shop also quite well, I had to leave Ludhiana following a disagreement with my father. This was about the withdrawal of funds from the shop, which we had named Hind Engineering Stores. While the shop was financially doing fine, it was still necessary to watch over the inflow and outflow of funds. My father and I had an unspoken understanding that he would tell me before he made any sizeable withdrawals from the shop. This way, I could make sure that the shop always had the funds to make the payments for the goods ordered from various sources. However, without telling me, one day he withdrew a large amount of money from the shop to bail himself out of the trouble in the workshop.

When I protested about this unexpected withdrawal, he didn't like it. Driven into a corner, he asked me as to who owned the shop. Since he was the owner, what right did I have to demand an explanation from him? I realised that this kind of a conflict would be bad for the family. Therefore, I took out the keys of the shop from my pocket, and handing them over to him, I told him that I was sorry about having questioned him and that I wouldn't go to the shop lest it precipitate conflicts within the family.

When this happened, I was preparing for appearing for my M.A. final examination. I realised that my days in the Ludhiana were numbered. I had to do well in the examination so that I would have no difficulty in getting an appointment. There was another incentive for studying hard. I believed I was in love but the young lady was unwilling to consider me for marriage because she was convinced that I was too much of a gadfly to do well and get a good job. I promised her that if she would give her consent, I would study hard and come first in the University. It was a great blow to me that she did not take my offer seriously. Nonetheless, I put in my best efforts and surprised her and everyone else by coming second in the University. At this remove, I am unable to decide whether or not she did me a favour by refusing my offer of marriage.

After the argument with my father, I felt like a stranger in the house. It was still the month of April and the results of the MA examination would be declared only after three months. During this period, I did not want to be a burden on the family. Therefore I started applying for all kinds of jobs but I could not get an appointment even as a bus conductor for the Punjab Roadways. It left me no choice but to grin and bear it.

Once the results were declared, I got a job as a college lecturer in English in September 1951. Within three years, I took a jump from this, first into the Punjab Civil Service (PCS), then into the Indian Revenue Service (IRS), and finally into the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), then rated as the most prestigious job in the country.

In the meanwhile, the criminal case against us had been withdrawn. My father was doing well in business. Others in the family too were doing well and we enjoyed a measure of respect in the community. I think we can say that, as a family, we were fully rehabilitated within seven years of the partition.

Epilogue

When I think back on our life in Ludhiana, I don't feel so bad. Yes, life was tough. We had to watch every paisa. Whenever we had to go anywhere, we walked. Later, I often borrowed my father's bicycle, but the rest of the family walked miles to school and back. Still, there was never any doubt that sooner or later we would overcome our difficulties.

In retrospect, I feel that living in a small town in a crowded locality also had many advantages. While living in Lahore, we were always on the move. Between 1933 and 1947, we changed our home seven times, so that we never had a chance to make friends. This situation was compounded further by the fact that from 1937 to 1943, I was not going to any school, on a regular basis.

In Ludhiana, we lived in a locality in which everybody knew everybody. In my college, because of my creditable academic record and extracurricular activities, I was a known personality. People respected me because I did well in spite of running a shop.

In retrospect, it seems that the Ludhiana experiences gave me a lot of self confidence. I made so many friends who have been close to me for more than half a century.

In the college, I was able to get away with breaking so many conventions and norms, largely because, without taking notes or putting in long hours poring over the books, I managed to score good marks. They did not know that when an examination was at hand, I put my heart and soul to read up whatever was relevant. I knew that if I did not do well in examinations, all my unconventional and original thinking would get discounted. People would put me down as a mountebank full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

I was a fairly successful shopkeeper. I took to heart the lesson that if you do not keep your accounts meticulously, you are bound get into trouble. Another lesson I learnt was that you cannot make the rules unless you are in command of the market. For some time, our shop was ahead of others because we had introduced many new products. When these became popular, we could command the market and lay down the prices for precision tools and Electroplating materials.

Another thing I learnt was that education was a great source of strength if you had acquired it not by learning only by rote but also by using your head to observe, discuss, reflect and evaluate the knowledge presented to you by others. My father and I were in the forefront of the Ludhiana Machinery Merchants and Industries Association only because we could formulate and present the requirements for Ludhiana's industrial growth to the State Government.

I had remarkable powers of concentration at that time. One day, Mr. Brij Mohan Munjhal, on behalf of the fledgling Hero Industries (now the leader of the Hero Group of Industries) came on a bicycle to buy a couple of kilo of glue flakes from the shop I was minding. I was reading Shakespeare's The Tempest when he showed up. To cater to him, I put down the book, weighed the glue, wrapped it up and handed it to him, put the money into the cash drawer, and as he was going down the steps, I picked up the book, and started reading without a moment's delay.

Brij Mohan Munjhal was intrigued. He came up the steps again, and asked me as to what was I reading. When I told him that I was reading for my M.A. examination, he wished me Godspeed in my studies, and assured me that I was bound to do well in whatever career I may choose for myself. Many years later I met him as Additional Secretary (Commerce) in the annual conference of the Engineering Advisory Council. He was then heading the multi-million Hero Honda Empire. He reminded me of his words and claimed some credit for my getting where I was at that time.

While I stayed in Ludhiana only for four years between 1947 and 1951, my father stayed on in Ludhiana till his last day. Until 1956, I visited home fairly regularly and therefore, continued to be a part of the community. For years after I left Ludhiana, people of many walks of life remembered me with pride, as one of their own, even though I had spent only four years there.

This was demonstrated in sharp relief in 1976 when UP's Public Works Minister visited Ludhiana. I was then Secretary of the Public Works Department in UP, working under him. Every one he met in Ludhiana told him that since he was UP's Public Works Minister: I, a Ludhiana boy, must be working under him. My old friend, Joginder Pal Pandey, whom I had coached in English when he was going to England, was then Punjab's Public Works Minister. He went out of his way to persuade my Minister to have breakfast at my parents' house. He himself carried the eatables on the tray to serve him the Dahi and the aloo parathas made by my mother. When my minister expressed his shocked surprise at the way he was acting, he told him that it was not a small matter that he was allowed to treat my parents' household as his own home.

Living in Ludhiana was a highly enriching experience. I can count more than ten friends who have continued to hold fast with me for more than fifty five years in spite of my many failings. I expect that when I am laid out for cremation, every one of them still alive will be there to see me consigned to fire. What else, I ask, can anyone ask for?

© Anand Sarup 2009

Comments

Add new comment