Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Growing up in Delhi in the 1960s and 1970s

Category:

Jamil Urfi's book 'Biswin Sadi Memoirs, growing up in Delhi during the 1960's and 70's' which is a nostalgic, personal remembrance of the bygone 20th century or the Biswin Sadi was published last year. Urfi was a campus correspondent for the ‘Times of India' Publication Youth Times during his student days in the 1980's. He has an abiding interest in history, architecture, period publications and popular cinema of the 1960s and 1970s-themes which figure prominently in his latest book. He is a teacher at the University of Delhi.

Editor's note: This is an extract from the author's book 'Biswin Sadi Memoirs, growing up in Delhi during the 1960's and 70's. CinnamonTeal Publishing, Goa, 2018.

Author's note: My family settled in Delhi in 1967 and lived in Nizamuddin East, a residential colony of South Delhi. My neighbours included several Punjabi families who had been displaced by the Partition, and an Anglo-Indian couple. In my neighbourhood also lived Mr. Ram Rakha Mal Chadda, aka Khushtar Girami (1902-1986), the editor and owner of the Urdu magazine Biswin Sadi. Extracts from my book with reference to Mr. Girami and others have already appeared in Scroll.in and The Friday Times (published from Lahore). In this extract from my book, I describe the general atmosphere of Delhi in the 1960's and 1970's, touching upon celebration of festivals and the social life of middle class Muslims in Delhi. In the process, I mention the interesting character of Hakim Abdul Hameed (1908 - 1999), the man behind the ‘Hamdard Foundation', and his famous get togethers at Eid.

Sometimes old memories appear in a flash when I think of a childhood spent in Nizamuddin during the 1960s and 1970s. For instance, I recall an elderly Sikh gentleman who used to sell country made sweets in our neighbourhood. He made his appearance quite suddenly, carrying his wares in large baskets suspended on the two sides of a pole delicately balanced on his shoulder. Silently setting up his shop and standing beside it for an hour or two, he vanished, without as much as leaving a trace only to reappear the next day, at his fixed time. Never speaking a word with anyone this elderly man was probably someone who had been displaced by Partition\; he looked quite old then, and by now must be dead.

I recall Khushtar Girami, the owner of Biswin Sadi magazine, dropping by for a chat. Sometimes, in the background, Anoo Kant my neighbour and childhood friend could be heard shouting ‘Keer-tae! Keer-tae!'-a throwback to those days of landline phones when no one had even dreamt of mobile telephony. It so happened that a girl called Kirti lived in the house just behind Anoo's. Since her family did not have a landline phone Anoo's number had been given to their relatives, who frequently made long distance calls. On such occasions, it fell upon poor Anoo to inform them whenever a trunk (outstation) call came, which he did by standing on his balcony and shouting at the top of his voice till someone paid heed.

***

The change of seasons and the festivals they bring in their wake is unique in each case. Right in front of our house, there was a large gulmohur tree which heralded the seasons well in advance. It remained bare and leafless in winter but with the first signs of spring, it started sprouting small, pale green leaves which multiplied rapidly till the whole tree acquired a dense, green crown. Soon the buds appeared and burst into red flowers, which fell on the ground forming a rich carpet of red and green. In the peak of summer, the leaves grew darker and then started turning yellow, falling like flakes of dandruff. Sitting in the front courtyard, getting covered by those tiny yellow leaves, one sensed that autumn was in the air. It was around this time when two very interesting characters made their appearance in the locality. One was a man who sold handmade violins and advertised his presence by playing the tune of the song, Saiyyan Jhooton Ka Bada Sartaj Nikla from V Shantaram's classic film Do Aankhein Barah Haath.

Whenever we heard this tune, we knew the sarangi wala had come and started coaxing mother to buy us one. The instrument, made out of bamboo sticks and a bulb fashioned out of a baked earthenware cup, was of course unplayable, and perhaps the only person who succeeded in playing it was the hawker himself. We could never extract any meaningful notes, except for some wailing sounds. So once the novelty of the sarangi was over, the toy was forgotten and kept away. Sometime in the same period, we also heard the twang of a very heavy string in the street. It was the dhunna- the cotton beater - who usually appeared at this time of the year, when the weather was changing and the time had come to take the quilts out for winter. With his instrument, the cotton was beaten, re-fluffed and stuffed back in the quilts.

This was the most beautiful time of the year, and soon a festive atmosphere would envelop the surroundings. First to come was Dussehra in which huge effigies of Ravana, Meghnath, and Kumbhkaran, all gaily decorated in coloured paper, were burnt. This event happened on the banks of the nullah, adjacent the Barapulla Bridge. At this time of the year, there is a nip in the morning air, and the atmosphere is one of gaiety and abandon. A number of different types of toys and locally made handicrafts were sold at Bhogal, and my father (whom we called Abbu) would go there in his car and return laden with all sorts of things-kheel (puffed paddy) and batashe (sugar drop candy), clay toys, and animal shapes moulded out of sugar. His favourite was paper lanterns, called kandil which had papers of different colours pasted on the sides. A lighted lamp was placed inside the kandil which produced a kaleidoscope of different colours and looked very beautiful in the evening.

A local troupe performed Ramayana shows in the neighbourhood, and Dedaji-Anoo's aunt read passages from the Bhagwad Gita, and retold the epic in her own way to us. The story was explained by elders as the fight of good over evil. One of the things which appears intriguing, in hindsight, relates to the toys made of cardboard, coloured paper, and bamboo sticks that were sold at the time of Dussehra-many of them being models of ancient weapons, such as bow and arrows, swords, a bulbous stick meant to crack someone's skull, etc. We bought them and fought mock battles but never questioned why such powerful weaponry had been used in the fight of good versus evil.

Soon after Dussehra came Diwali, announcing the setting in of winter, which meant long, dark nights and getting up to go to school in the bitter cold mornings. After what seemed like months and months of cold weather, things began to change and the air became clearer. The gulmohar tree, which had been bare all these months, suddenly sprouted leaves as Basant Panchami and Holi were on their way. At this time, the neighbourhood boys formed groups, and battles with water balloons used to ensue, sometimes erupting as wars between different gangs. The colours used during Holi were sometimes so strong that they would remain on the skin for several days afterwards. Usually, the day after Holi, one came across people coloured in different hues of purple, magenta, silver, and red.

But it was always on Holi that one Good Samaritan in the locality, a certain Mr. Chaddha (different from Mr. Ram Rakha Mal Chadda already mentioned) and his family, who lived a few houses away in the same block, would get into organization mode. Along with some others, he organized a Holi Milan, mostly in the Khajoor Wala Park to which all the residents of the locality were welcome. The programme consisted of a number of entertainment items such as skits, short plays, comedy items, and songs. In many of the on stage presentations members of the Chaddha family themselves used to participate. Songs were sung, and on one occasion, I remember a woman sang the famous song Dum maro dum from the film Hare Rama, Hare Krishna, to the accompaniment of guitar.

Close to the Hazrat Nizamuddin railway station, there was a market from where we got our daily groceries. For bigger shopping, the place to go was the market at Bhogal, a couple of km away. There were two routes to Bhogal. One was through the Khan-i-Khanan's Tomb, crossing the bridge over the nullah, along which a new flyway now runs. Another was a slightly longer route from Rajdoot hotel to the Barapulla Bridge, an ancient bridge close to the Nizamuddin Railway station, where in a garbage dump there would be stray pigs feeding.

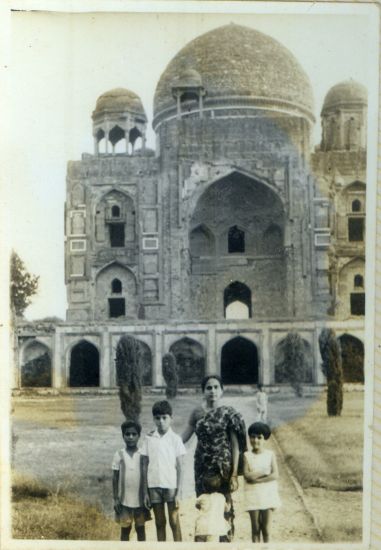

L to R: a friend (name unknown), author, Mehjabeen Jalil (mother), Tabinda (sister), Rakhshanda (sister). Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan's Tomb in Nizamuddin East, ca 1968.

Khan-i-Khanan's Tomb in May 2019. The monument is in the process of being repaired and restored with the involvement of a prominent heritage organization.

It was here, once while returning from shopping, trudging along with sacks full of groceries that, a little girl in our group made a funny remark about the music teacher-an Anglo Indian lady, in her school. Since this bright, perceptive girl knew that Anglo Indians consumed pork, which is haram (forbidden) for Muslims, on seeing pigs feeding in the garbage she said, pointing towards them, ‘My gana teacher eats piggi ghosht' (My music teacher eats pigs' meat). Putting two and two together she had come up with a perfectly logical sentence using a combination of Hindi and English words. This remark of her's created quite a sensation at that time and was much remembered later for its ingenuity. It was also a commentary on how different communities were perceived by others and the stereotypes that existed.

***

Radio was very popular and a constant source of information and entertainment in those days. People at home used to listen to All India Radio or BBC Urdu and Hindi service with rapt attention and discuss ‘news'. During the late 1960s, a hugely popular weekly film music program known as Binaca Geet Mala (Binaca, after a popular brand of toothpaste) was hosted by the inimitable Amin Sayani. It featured the hit songs of the week-to use today's lingo, ‘what's trending this week' but it was really Sayani's style of presentation that was the hall mark of the show.

Just after Binaca Geet Mala, there used to be another popular program called Johar Ke Jawab in which the witty I S Johar, a Hindi film actor known for his idiosyncratic brand of humour laced with sarcasm, used to answer questions posed by listeners in his characteristic style. Of the music programmes, my sisters, being much more suave and trendy than I was, preferred to listen to popular western music on shows such as ‘In the Groove' and ‘A date with you'. These played the musical hits of the 1940s, 50s, and 60's, numbers sung by Paul Anka, Elvis Presley, Harry Belafonte, Archies and the Beatles. My own radio tastes were quite provincial or ‘desi' in contrast, since I loved listening to programmes in Hindi like Vividh Bharti ka Vigyapan Karyakram and also Bhoole Bisre Geet-a program which used to play long forgotten Hindi film songs.

Towards the end of 1960s, television made its appearance in the form of Doordarshan. One of its characteristic features was its montage, which looked like a hypnotic disc and could be seen rotating on the screen to the accompaniment of the signature tune of Doordarshan, mesmerizing people in the process. In its earliest days, telecast was just for a few hours starting from around 6 pm or so. After the rotating hypnotic disc on the screen and the music ended, someone finally appeared on the screen.

Often it was Pratima Puri, sometimes Salma Sultan, with a namaskar at which the audience became thrilled and electrified. Some people attempted to return the greeting by folding their hands to say Namaste but soon realized their stupidity and looked around sheepishly. Many a times, especially in the early years of Doordarshan, due to technical difficulties, the telecast would be suspended and a message announcing, ‘Rukawat ke liye khed hai' (‘Sorry for the interruption') appeared on the screen. The line ‘Rukawat ke liye khed hai' became a part of people's vocabulary later on.

As with most other middle class families of that period, all things eventually came, but at their appointed time. First, it was the fridge, then a car. The TV however took a long time to come. In our neighbourhood, we were not among the first families to get a TV set and the reason was simple-we couldn't afford it. So to have a taste of the much talked about television, I used to go to a neighbour's house. Generally, it was at the family of Diwans-Mr Diwan, Mrs Manorma Diwan, and their two daughters, who were family friends and lived in a house closeby. To give me company while watching TV, there would be some domestic helpers and some neighbourhood children. Sometimes, one of the Diwan girls would also join in.

We all used to sit on the floor, where a mat or a durrie had been spread, and watch all the programs with boundless enthusiasm, starting with Krishi Darshan, which was a programme about the latest in farming and irrigation technologies. While this was at times boring, as the days passed, Doordarshan began adding several interesting programs to its repertoire. There used to be an interesting quiz show called Prashan Manch hosted by an elderly, bald gentleman called Tandon. Then of course there was the inimitable Melville deMellow who used to host discussions on current affairs and political events. The biggest draw some years later was the half hour program of Hindi film songs known as Chitrahaar. This programme remained so popular, even till the 1990s, that senior people including university professors and officers would be heard discussing Chitrahaar of the previous evening. In this programme too, certain things were predictable. For instance, on Republic Day and Independence Day patriotic songs such as ‘Mere desh ki Dharti' were compulsorily aired.

Eid celebrations

Although we were Sunni Muslims, most people in our family were surprisingly well steeped in the Shia traditions, something which I can only attribute to their having a wide spectrum of friends cutting across sectarian or religious divides and also being associated with the city of Lucknow at one stage. Though, ofcourse, there were the common jibes and jokes attached to Shias and Sunnis but what I remember most is Khichda (also known as Haleem) being cooked at the time of Mohurram. We also made some token observances like wearing black clothes on the day of Ashra and sometimes joined in the Majlis sessions-literary events in which marsiah (a form of Urdu poetry) is read and the assembled crowd participates in a ritualized form of mourning known as matam.

But the most significant festival was Eid-ul-Fitr, at which every time, there would be a controversy regarding the sighting of the moon. Whether the moon was sighted in the town or not? In one city it was but in another place close by it was not. Why didn't they print the predictions of the moon sighting for a century in advance and end this confusion once and for all? Though all acknowledged that there was too much power in the hands of mullahs with respect to sighting of the moon and declaring Eid, beyond a point, no one seemed to be willing to do anything to end the confusion. But as children, we were very excited about it and climbed the roof to see the new moon. Our neighbour Mrs Andrews happily obliged by permitting us to climb the roof of her flat to get a better view of the evening sky. It looked like a thin arc, barely visible in the sky, and once sighted, there would be murmurings of ‘Eid Mubarak' all around.

Everyone looked forward to Eid, planning weeks in advance. The house was cleaned, curtains changed, and new clothes ordered. While for me and Abbu, Eid clothes only meant a new kurta-pajama set, for the ladies in the house all sorts of fancy, lacy dresses, a gharara or shalwar kameez of brilliant, shiny material were ordered. A lot of time was spent discussing what would be worn on Eid because it couldn't be the same design or colour as last year and had to be different.

On the D-day, there would be a buzz in the air. Abbu would be the first to get ready and we would together go for offering the Eid namaz. It seems, who went where for the Eid namaz could be an issue of some significance, for some. The rich and famous and the influential went to either Eid-gah or to Jama Masjid in the walled city because that is where the Who's Who of the city also came. Abbu, of course, chose practicality over prestige, and so we always went to the closest place, the Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah, just a short distance away. And if we were late, which we usually were, then there were plenty of other mosques in the neighbourhood where we could catch the second shift of the congregational prayer.

On returning home from namaz, we would find the house looking clean, all the ladies dressed up in their finery, and delicious food on the table. There would be the customary offering of Eid greetings - hugging three times followed by a clamour for Eidy, a token cash, amounting to just a few rupees in those days, which children are entitled to receive from their elders for buying sweets or toys.

Meanwhile, there would be a stream of visitors. Anoo came first followed by the Sharma's, Khushtar Girami, and other neighbours, including the Razzak sisters, and their brother Sohail, and our family friend Tariq. Greetings would be exchanged as well as an account of the experiences at the namaz on that day. Generally something noteworthy or funny would have happened to someone. Some blunderous, clumsy thing which someone did. For instance, there was this incident of a little girl who had accompanied her father to the mosque which I remember very well. While the namaz was in progress, the little girl probably grew bored and restless just sitting around while the men were busy with the rituals. Wanting to convey something important and urgently to her father, she said loudly, ‘Abba! Abba!' Not realizing that Abba couldn't respond to her at that time as he was in direct communion with God, she demanded, in a very loud, shrill voice, ‘Abba! Abba! Sunte kyon nahin?' (Abba, why aren't you listening to me?)

Everyone during the course of the prayers heard that remark and the whole congregation burst out laughing. For a brief moment, the otherwise sombre gathering was transformed into a quivering mass of mirth and laughter. Humanity had triumphed over organized religion. I wonder if the numerous angels of the Great Almighty were on duty that day. Surely they would have heard and seen what had happened on Earth down below. I would like to think that on some occasions God, the most beneficent and merciful which he is, is likely to forget the priests and mullas. Rabindranath Tagore puts it in a much better way when he says:

Children run out of the temple and play in the dust

God watches their games and forgets the priest.

Many of our Eids were celebrated at Pilibhit, at my paternal grandmother's home, which was a different experience altogether. While in Delhi we offered namaz in grand mosques built during the reigns of emperors and kings, in Pilibhit it was a more rustic experience because for offering the customary namaz, we went to the local Eid-gah which was on the outskirts of the city. It was close to the railway bridge across the river Deoha, a distance of a couple of kilometres which had to be walked since there was no motor-able road in sight. On the way, one came across little boys and girls, wearing their best clothes, accompanying their fathers or uncles, some on bicycle, some on shoulders and others just walking in their tiny strides holding the hands of elders. There would be the usual shops on cycles or trolleys, selling balloons, small plastic toys, sweets and ice candies- the whole scene strongly reminiscent of the journey to the Eidgah in Prem Chand's classic short story by the same name.

On all the festivals, Eid-ul-Fitr, Baqr-eid, Holi, Diwali, etc., Hakeem Abdul Hameed, the man behind Hamdard Dawakhana Trust, makers of herbal products like Rooh Afza, Panchnol, Safi, Roghan Badam Shirin, Sualin, Joshina, Cinkara etc., organized a get together at his palatial home in Chanakyapuri. It was then that we got to see this fascinating personality, said to be a self-made and an extremely hard working and intelligent person. At Tughlaqabad, he had set up an Institute for Studies in Indigenous Medicine, which later formed the nucleus around which grew a university known today as Jamia Hamdard.

Attending Hakim Sahib's Eid get-togethers was a regular event for us, which we looked forward to eagerly. I still remember driving from Nizamuddin to Chanakyapuri, passing along the sun dappled, leafy Lodhi Road on the way and the Safdarjung Tomb en route. At the venue, as always, Hakim Abdul Hameed would be standing at the gate, personally welcoming the guests. Abbu used to proudly introduce his family. I hated this part because I had to put in extra effort for carrying out polite social conversation. Fortunately, there was always some company at hand.

I would like to think that the Eid-Milan's at Hakim Sahib's house served several purposes. Primarily, it was an occasion for networking, hobnobbing with the high and mighty, because some politicians and ministers would usually be present there (cultivating the ‘Muslim Vote bank', to put it rather cynically or ‘sensing the wind' in the Muslim world). This was also an occasion for us to reinforce our Muslim cultural identities in the sense that such social gatherings also served as a rehearsal ground for practising North Indian Muslim etiquettes. Trying to hold a conversation laced with high Urdu. People offering different types of adaab and salams. People judging each other and testing relationships, and above all, practising speaking chaste Urdu laced with shers (couplets in Urdu).

This was the place where one was likely to hear one of the most clichéd of Urdu couplets written in context of Eid, which is, ‘Eid ka din hai, aaj to gale lag ja zalim, Rasme duniya bhi hai, mauqa bhi hai, dastoor bhi hai.' This couplet, whose original author seems to be unknown, while at one level is an invitation to hug the enemy and forget past differences on the happy occasion of Eid, can have another meaning too. Say, at another level, it could be looking for an excuse to touch the beloved, under the pretext of offering her/him Eid greetings. After all, hugging friends, relatives and even strangers on Eid is a long established custom (dastoor), an opportunity (mauqa) as well as common practise (Rasme duniya).

For some of the guests, I suspect Hakim Sahib's Eid Milans could also have been an occasion to hunt for prospective brides or grooms. Perhaps, it was on account of this, that the mothers of girls encouraged their daughters to wear their best clothes, and be all decked up like typical Muslim brides, donning the ghararas and dupattas which their great grandmothers had worn a century ago at their own weddings.

______________________________________

© Jamil Urfi 2019

Add new comment