Latest Contributions

Chapter 4: Learning and daily routine

Category:

Tags:

Visalam Balasubramanian was born in Pollachi, on May 17, 1925. She was the second of three children. Having lost her mother at about age 2, she grew up with her siblings, cared for by her father who lived out his life as a widower in Erode. She was married in 1939. Her adult life revolved entirely around her husband and four children. She was a gifted vocalist in the Carnatic tradition, and very well read. Visalam passed away on February 20, 2005.

Editor's note: This is Part 4 of her memoirs, which have been edited for this website. Kamakshi Balasubramanian, her daughter, has added some parenthetical explanatory notes in italics.

Nov 92.

I have been writing only about my childhood. Now I think I will go into a later phase beginning with a motor car!

Learning music

My father did not fancy sending us to school. He thought he could give us a more varied type of education at home with hired teachers. My grandfather made a beginning with hiring a lady to teach elementary lessons in Carnatic music to my sister, as well as play on the harmonium. My father changed it - almost in a hurry, so to say, as though he woke up to a dream - and got a real, good professional vidhwan (learned person) Sri. Erode Viswanatha Iyer to teach music. My father got my sister and me lovely violins.

In learning music, we were made to do rigorous practice.

Visvanatha Iyer was a violinist (recording here with a great percussionist's accompaniment) but he could teach vocal singing very well. He was good natured. My sister and I practiced on both the violin as well as singing. My memory of the various music teachers is: Mr. Visvanatha Iyer handled us and the music itself in an easy way. We did not feel it was a hard science or an elusive difficult art. He was always giving us a mixed fare. Small simple varnams and kitanams were taught with big ata tala varnams and big irandu kalai chavukka kirtanams. No fuss was made about the big ones nor were the smaller ones treated lightly. In between, he would teach us the aarohana avarohana kramam, janyam, vakram, visesha prayoham, etc. without it even sounding like an exercise. Subtly he set up competition between my sister and me. And we never knew which one of us he favoured.

But there were always jealousies among aspirants who wanted the money, privileges and prestige of being in my father's employ. Visvanatha Iyer's brother, Mr. Krishna Iyer, who was a flute player himself, was one of those talking slightingly of Visvanatha Iyer and his methods. On the number of occasions when he stepped in, Gowri and I did not like him, so he could not continue.

Next was one Vadakkanchery Rama Bhagavathar. He was a martinet. Being then a bachelor, he had all the time to sit with his students. He was also the music teacher to one Radha, wife of the Income Tax Officer at Erode at that time, Mr. Achutan Nair. He never taught us any theory or grammar of music.

Then one Tirumalachariyar from Madras was engaged. He taught us many songs in quick succession, averaging one kirtanam in three days. He gave us a sound knowledge in raga lakshanam, writing out everything in minute detail. He did not last even six months, I think, owing to misrepresentation to my father by ignorant men. If we had had the opportunity to learn from him, we would have equalled professional musicians. It was he who taught us the correct order of the 72 mela karta ragas, the meaning of upangam, bhashangam, ragangam among janya ragas and vaadi, vivaadi dosham.

Visvanatha Iyer had taught us prakruti and vikruti swaras, as also the different positions and the names of swaras such as suddha rishibam, chatusruti rishibam, etc. Tirumalachariyar was a conscientious man but not competitive.

Then came Vadakkanchery Mani Bhagavathar, older brother of Rama Bhagavathar. No doubt, he gave us good practice in singing ragam and swaram - we having been supposed to have come up to the senior level. It was nearly four and a half years of training, our own rigorous practicing, and listening to concerts by then.

When my sister got married, all the tuitions came to a stop.

Gopalaratnam - usually called only Ratnam - a grandson of my athai (aunt) by her married daughter, had just then graduated out of music college at Annamalai University, Chidambaram, mainly due to my father's exhortation to take up music as his profession. He was in the habit of spending his vacations at our place in order to benefit from my father's connection with performing musicians of those days. So, on completing the course, he came to my father to be put as apprentice to some senior vidhwan. While waiting for it, he stayed with us for a month or two. At that time, I learnt a lot of classical and light songs from him. Since we used to practice together, both of us benefitted in improving our styles of singing.

Daily routine

At times, when we were learning music together, Gowri and I would play on our violins - each sitting facing a wall - in separate halls (she in the front hall and I in the eating hall, as we called it!) from 4.30 a.m. to 5.30 a.m.!

Then do physical exercise with my father when my brother also joined, lifting, bending with Cecil dumbbells, dandaal (push-ups) and sit-ups till 6.30 a.m. Then have a cold bath, including the head. Since Gowri had thick, dense, black hair, her tresses never dried properly. And she always had a nose block and swollen tonsils. She suffered from urticarial rashes every single day, which must have been due to her allergy to gingelly oil and cold water. But it was never diagnosed as such, and she continued to suffer till she got married and went away. She also suffered from lack of sleep, but my father was something of நான் பிடித்த முயலுக்கு மூன்றே கால் (someone who obstinately and unreasonably sticks to a position) type. He believed his ambition was the only real thing, and whatever others said to the contrary was due to either ignorance or jealousy.

This early morning (pre-dawn, I'd say) routine went on for 2-3 years. On the insistence of my grandfather and Coimbatore uncle who never gave up telling my father that he was taxing us, he stopped it. Then he changed it to taking all of us to the river Kaveri, which ran 3-4 miles from our house for our morning bath. It was also timed between 5.45 or 6.00 a.m. to 7.15 a.m. My grandfather and father both stuck to correct, proper timing for everything they did. They could not brook deviation. Lethargy and laziness infuriated them.

My father hardly ever spoke about our mother. He used to say she was artless, guileless, extremely simple. Physically, not a strong person. Did not know a thing about housekeeping, cooking. He felt he never recognised her virtues. Kandappan and our athai had only good words, kind thoughts for her. My grandfather never once said anything positive about her. It was always: she was fond of overeating, didn't have a good singing voice, was always slow and dull.

By 8.00 a.m. we had our limited breakfast, dried our hair, put on crisp, washed fresh dresses.

My father would have by then gone round placing flowers on the pictures of deities and lighted incense sticks. Whenever anyone thinks of my father, it is the smell of very good, quality scent of perfumes that was always part of him and the fresh look of the three stripes of holy ash on his forehead that would come first. He was a lively man. A live-wire. One could never see him looking sleepy, sad, dull or even relaxed. He was often worried but it never showed on his face. Never. So, by the time we came up dressed, there he would be with fruits. Peeled, if oranges. Cut, if apples, cut and sliced bananas.

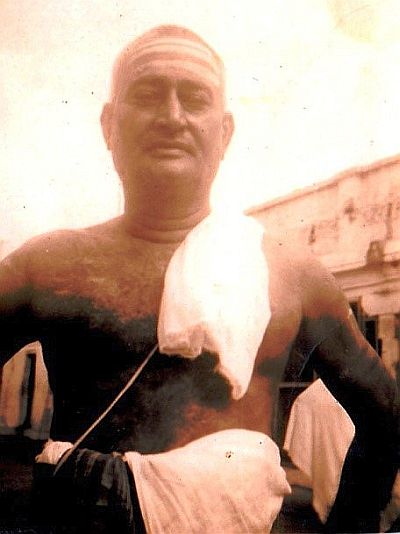

Visalam's father, C. V. Srinivasa Iyer, Babuji to his grandchildren. Circa 1950s

He had fixed ideas about how much one should eat. He hated overeating. We were ourselves moderate to poor eaters. The elders in our family were sticklers for table manners. They were very happy those manners came to us naturally.

Pomegranates and grapes came from faraway places. Quetta pomegranates, Kabul grapes. Sapotas were brought from Madras. Mangosteen from Courtallam. There were three months of mango season. The Muslim traders used to bring chosen mangos in hundreds - 150-200\; sometimes 50 unripe, 100 fully ripe\; they would spread hay in a room, place the fruit carefully spaced out, cover it again with a layer of hay and go away, either collecting money for it later or adjusting it towards their loan.

After the fruit eating session, it was time for music until lunchtime, which was between 12.30 and 1.00 p.m. Then Parvathy mami braided (plaited) our hair, and we changed into fresh clothes again. Promptly, exactly at 2.00 p.m., our tutor arrived. Our English, arithmetic, etc. lessons went on till 4.00 p.m. We had a hurried cup of tea, put on socks and shoes and went out by car to go for our walk, which had to be two miles. Kandappan and my father walked both ways - to Miss May's and back, about six miles. Occasionally, my father used to treat us to some hot snacks or sweets at the Indian Refreshment Room at the Railway Station or else buy chocolate or ice cream at the stall there.

My grandfather believed in fresh air and outing in the evenings. Our evening outings were different at different times.

When we were young. I.e. before I was say, seven, Kandappan used to take us out in a big pram, a tricycle and one of us walking. It was always Gowri walking (she was heavy for the pram), Nagu and I alternating between the tricycle and pram. Later it was walking not less than two miles.

For some time it was playing tenniquoit (also Tennikoit or Ring-tennis), badminton and ping pong in one of the government officers' quarters' compound. That way we were made to get acquainted with older "society" ladies.

Actually, we were completely in my thatha's (grandfather's) charge till I was 8 or 9 years old. As such, as long as he was moving around, my grandfather never missed his evening outing. By car and not walking from the time my father bought the first car in '33. So, there was a period when my thatha would come in the car to pick us up from Miss May's (needlecraft teacher) house, after his short open air stay in the park, at 6.00 p.m.

When we were very young, below the age of five, he used to take Gowri and me somewhere near the canal, and let us play under the trees. And in the evenings he regularly took us both to the munsif''s (lower level judge)court, a 100 yards from our house, which had a big, sand-filled compound, or to a Kounder's firewood shop, which again had a lot of open space and a number of neem trees.

Only later my father took over his style of regimented schedule.

As was his nature in everything, when my father thought of something and fancied it, he went all out to get it. Nothing could stop him. If he did not know enough of that subject, he bought books, consulted any number of people in that profession and, although he got misled by some sycophant, he never let go of his goal and continued in his own spirited way, sometimes by group discussions, confrontations, to get his doubts cleared, himself educated. Thus, in Carnatic music he got all the leading vidhwans of the day, learned theorists to come to our house and discuss, give demonstrations and even sit with us while our own music teacher was giving us lessons. Thus, a teacher had to be very careful how he instructed us at every step.

The same went for our English lessons. After trying a few teachers, my father engaged one Sri. K. G. Ramakrishna Iyer. It was a pity that Sri. K.G.R. (Using initials is a fairly common way of referring to people in our part of India) was not given a free hand, for he was a very good, capable, committed teacher. He was proud of his work and enjoyed teaching. My father's idea was that good correct English and simple arithmetic was all that was needed to make us fully "educated." But Sri. K.G.R. insisted on introducing us to geography, history, science, mathematics and Tamil.

He could succeed only half way! My father would not let him continue with European history, absolutely no science, certainly no need for algebra and geometry. My father never favoured Tamil. But K.G.R. got our clerk Lakshmanan to get us volumes of Tirukkural and a book பெண்மதிமாலை (Penn Madi Maalai Woman's Wisdom) by the renowned writer Vedanayakam Pillai, a Christian. My father gave in, in a sort of concession, for these Tamil books.

(Recording of a song by Vedanayam Pillai performed by one of my mother's music teachers, Rama Bhagavathar, who was a well-known vocalist in the Carnatic tradition).

Beyond text-book learning

Now, my father thought, home tuitions will give us knowledge of English, no doubt, but we wouldn't be able to speak fluently unless we practise it with speakers of English. Also, we had no way of learning to move and mix with grown up ladies of society!

And so it was that we had to go to Miss May Narcissus' place for learning needle work (I think it was a few months in '34 and '35.) We would drive to her place by 4.30 p.m., finish with her by 6.00 and return home walking, always accompanied by my father and Kandappan.

Miss May was a devout Catholic. A very religious person. She went to church twice daily. My father habitually generalised and categorised people. Thus, he said Anglo-Indians were totally immoral. He asserted that there never was a spinster who was a virgin in that community. My grandfather did not like that kind of talk.

This coloured and influenced our thinking, too. We seldom looked upon people with any respect for their character or principles. True enough, there were people who were very superficial but my father, even when he could separate the chaff from the grain, was loathe to grant that there was worth in somebody's genuine feelings.

There were many Anglo-Indian men and women, whom we came to know mainly because they borrowed money from my father. The Anglo-Indians we knew were not proud or arrogant. They knew that they were neither here nor there. They had a way of living and they maintained the style. Miss May had one brother, two step sisters, and step brothers. At times, we used to give a lift to Miss May to church, and sometimes take her out with us for picnics. She always behaved correctly and also taught us "proper lady-like" behaviour.

Though my father was very pleased in the beginning with the way we extended our hand for a handshake, politely passed on such things as a needle or a pair of scissors, or said "thank you", he later began ridiculing it as alien and artificial. For some reason my father thought that once you stopped taking tuitions from someone, then you sever all your connections with them and must not see them. That way, we avoided seeing Miss May and her sisters, her parents, even hiding when they came to our house.

We could have continued to go to Miss May's house for some more time and learnt sewing. But my father thought that our tailor, Sarwar Khan, could do it better and no tuition fee had to be paid. No doubt he was a professional tailor but either his method wasn't all that good or we never had any respect for him and could never take lessons from him, with the result that we hardly learnt anything worthwhile. The unsavoury result was: he was being summoned, dragged out of his shop and held in our house for hours and hours.

And we wasted his time laughing, imitating his ways of remarking, like: "What's this? The stitches are like a green tamarind!" He had a gruff, low-pitched voice. We spoke like him. He was probably an illiterate, so some of his pronunciation was funny. Naturally, he couldn't afford to neglect his shop and once he said to Kandappan, "I'm unable to watch my shop, Kounder," which Kandappan repeated to my father. My father was infuriated. He told Sarwar never again to come to our place. Though Sarwar apologised to my father and entreated him to see his point of view, even saying that if he was to repay loans to my father himself, pay the rent for his shop, he needed to work. My father wouldn't listen. I am unable to see why my father couldn't understand a poor man's circumstances.

True it was that my father may have helped him once, but if Sarwar wanted to rise again and stand on his own legs, my father should have seen the correctness of it. Pity. He didn't.

On other occasions, my father helped a few others (to my knowledge). He may have helped many more. I may not know, it so happened that they didn't have to work for us. This man - tailor Sarwar - knew a craft, and we were to learn it, but didn't. That was the unfortunate thing.

______________________________________

© Kamakshi Balasubramanian 2015

Editor's note: I approve all comments written by people. The purpose of the approval process is to prevent unwanted comments, inserted by software robots, which have nothing to do with the story.

Comments

Add new comment