Latest Contributions

Uncle Ponnu

Category:

Tags:

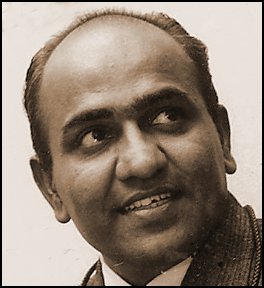

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

Editor's note: This story is reproduced, with permission, from Mr. Nagarajan's not-for-sale book of his memories, A Pearl of Water on a Lotus Leaf &\; Other Memories, 2010.

My mother's brother, Uncle Ponnu, was a man apart: apart from good looks, apart from erudition, apart from any social life outside of his addiction to alcohol and the automotive world of the C. Perumal Chetty (CPC) Motor Service, where he worked as a bus conductor.

Low in stature and ungainly, he was a bachelor not by choice but by lack of choices. His face, which hinted of a hundred thousand hangovers down the drain, was heavy, eyes reddish and fierce like his body, which suffered from a congenital deformity. His hands were clubbed, bowed inwards, and the forearms markedly short. All this made him look grave and unfriendly.

But, if you were able to strip this mask off his persona, one of God's kinder souls with a heart of gold, full of love and compassion, would emerge. He could never hurt a fly. He was affectionate, gracious and human. While drunkenness was the leading cause of his indiscretion, there were times when his one-track mind gave itself to fits of unparalleled humaneness and impulsive generosity. Sometimes I wondered, looking at him, why God should indulge himself in a trivial sport such as this and craft an exterior so inimical to the truth within.

He was my mom's youngest sibling. He had two brothers whom he hated. They were not in any case hugely accomplished. The eldest brother was Subramanyam ('Challa Mama' for us children\; 'Mama' in Tamil means maternal uncle) and the next was Vaidyanathan ('Vaithu Mama'). I don't know why my grandparents named their first two sons with high-sounding names and chose to call the youngest as Ponnu Swamy, a very unusual name in a Brahmin Iyer family though "Ponnu" meant gold. We called him 'Ponnu Mama'. My mother addressed her brothers as "Chella", "Vaithu" and "Ponnu".

Chella's achievement in life was that he was able to end up as personal secretary to company big wigs. His addiction was chewing paans and tobacco. His brother, Vaithu, with his ability to make the most of his meagre talents, worked for a well-known business house in Madras that sold branded clocks and watches. He was tall and handsome, spoke English and invariably dressed himself immaculately in well-tailored suits. But this successful phase of his working career was prematurely cut short because of a serious indiscretion, which cost him his job. There were hushed words going round the family that he too had his own addictions- to women and a sophisticated appreciation of alcohol and the heights of its ecstasy. He had short stints with small jobs here and there and finally ended up as an uncrowned adviser to our family.

Ponnu's case was different. I don't think he went to school but he could sign his name stylishly in English as 'K.P. Swamy' with his left hand. If the secret of Samson's strength was in the locks of his hair, uncle Ponnu's was in his deformed hands. He had mastered the art of using his hands to do anything he wanted. He could lift huge weights, ride a bicycle, and while eating with his hand even transport rice and rasam from a banana leaf neatly to his mouth. He loved smoking beedis, only 'Managlore Ganesha Beedis'. He was a good cook too. On some days, when he didn't attend office, he would cut potatoes and onions briskly and fry bajjis in the afternoon for all the children. There was nothing he couldn't do except, of course, order his hands not to touch liquor.

The CPC Service had its office in downtown Mysore, next to a popular cinema house called "Krishna Talkies", a stone's throw from the city's Clock Tower. The company had a fleet of passenger buses with which it connected most of the important towns in the State with Mysore city. Ponnu Swamy had found the job of a conductor with the company after his father's death and his mother (my grandmother) had decided to leave Mysore to stay with her daughter (my mother) and her family elsewhere in the State.

My father, who was a doctor in the Mysore Medical Service, was often posted to hospitals in remote areas in the initial years of his career. During this time, Ponnu stayed in a hotel room not far from his office and ate his meals in Udupi Krishna Bhawan, a well-known eating jaunt near the clock tower. Perhaps, it was during these years, when he stayed away from the family, he took to the bottle. It was a routine thing do for most CPC drivers and conductors to help themselves to a drink or two after they returned from their tiresome bus trips and then go home.

During the years when the family was away from Mysore, Ponnu Mama, made it a point to visit us, wherever we were, especially in the festival season. Every Diwali he would arrive with bags full of crackers, fruits and vegetables and packets of sweets and titbits for us. We looked forward eagerly to his visits because of the goodies that came with him. But, things became easier when once my father was posted back to Mysore to serve in a city hospital. The family found a rented home. We got admission in schools and colleges. Ponnu Mama left his hotel room and came home to stay with us.

It was during this period, I was able to look at uncle Ponnu and his life closely. Since he was among the senior conductors, the company wanted him to go on bus trips to remote places, which required a night's stay at the destination and return the following day. Hence Ponnu Mama came home on alternate days and spent the night with us.

On the days his bus was expected back in Mysore in the evenings, my mother would assign one or two of us to meet him at the bus stand near the CPC office to receive all that he would bring for the home like vegetables, coconuts, rice and sometimes even bundles of firewood. He would buy them at low prices in the villages and small towns on the way. This gesture by the brother was well appreciated by my mother since it meant a big support in kind to run the large family that required more money than what father brought as his salary or pension. We, on our part, were very keen on taking on this assignment because it meant for us a grand treat at Krishna Bhawan in the evening.

My elder brother Jagga and I would reach the bus stand well ahead of time and wait sitting on the steps of Krishna Talkies for the bus to arrive. The moment the bus came in, uncle Ponnu, dressed in khaki trousers and half-arm shirt and sporting a stylish pair of sunglasses, would get off, run to the back of the bus and briskly climb up to the top. He would then throw down baskets and gunny bags containing all that he would have brought for home. The cleaner boy, his obedient assistant, would catch them deftly and group them in a corner. Uncle Ponnu would then get down, look at us grumpily and gesture towards us to wait. He would then walk into the office with his leather bag full of cash and ticket books to submit accounts and hand over the cash to the accountant.

Let me digress here a little to explain a stratagem. Every time, uncle Ponnu came home after a trip, his side pockets would jingle with cash. Where would the money come from? From what are called "cut passengers" (short distance travellers, mostly villagers) from whom the bus fare would be promptly collected but no tickets would be issued. This money, which would amount to a few hundred rupees on every trip, would remain unaccounted and go straight into the conductor's pocket. Uncle Ponnu was a master of this trickery. Invariably, he would never get caught by checking squads on the way organised secretly by the company. He had his own paid informers who would caution him in advance of any impending danger.

There were also some days, very rare, when a sober uncle Ponnu would return home in the evening with a grumpy face\; no cash in his pockets and, of course, no goodies too. They were the unlucky days when he would have been caught by the checking squad and suspended from duty. He would then stay back home on 'leave' and invariably spend the evenings sitting on the steps of Krishna Talkies, hoping to be called in by the boss and pardoned. After a few days of waiting, he would be called in, reprimanded and reinstated considering his long service and loyalty to the company.

It would take roughly an hour for Uncle Ponnu to complete the job of submitting accounts. He would then come out smiling and take us straight to Udupi Krishna Bhawan and treat us to a generous tiffin consisting of Benne Masalas, Kesari Baths. And what have you. As we came out of the hotel, he would whistle to summon a tonga (Mysore's famous carriage drawn by a single horse), get the baggage loaded and see us off. It was understood that he would follow after 'finishing work'.

Not before nine or ten in the night, long after the family dinner, a tonga would stop in front of the wicket gate from which a slightly unsteady and stenchy uncle Ponnu would get down. If my father were sitting in his chair in the hall, he would walk in quietly, have a bath and change clothes. My mother would then escort him into the kitchen and give his dinner. While eating, he would conduct a slurred conversation with the sister giving her details of things he would have brought. This was considered as routine and a normal homecoming of uncle Ponnu. No one, including my father, would say anything. Next morning, by the time all of us woke up, my mother would have seen him off for work after his morning coffee. But there were also days on which uncle Ponnu's return home in the night would cause a lot of embarrassment to everyone, especially to my mother.

I remember a winter night when someone knocked on the door. My father got up and switched on the front light, opened the door and looked out. A tonga stood at the gate. Two men were struggling to help a nearly passed-out uncle Ponnu to get down from it. They managed to bring him in and laid him flat on the floor in a corner of the hall where all the children were sleeping. They told my father that they had found him lying on the road, not far from the tonga stand near the clock tower and left without saying anything more. They were tongawallas who knew uncle Ponnu and in whose tongas he would have returned home many a time.

Uncle Ponnu's whining and blabbering woke up almost everyone. "Your brother", told my father curtly turning towards my mother and left the scene after ordering all of us to go back to sleep. Tapping her forehead, my grandmother uttered a curse: "I would rather see him in the grave than in this state." Her son's inebriation frightened her. Whenever her brother was drunk and brought home in a hapless state by strangers, my mother's position in the family suffered. She had no words to defend herself against my father's fury.

When everyone had left the scene, my mother gestured to me and my brother for help to haul up her brother and shift him into a room. As we moved him, he kept talking to his sister\; most of what he said made no sense. His speech was slurred and he kept coming up a little too close to me as though he was attempting to tell me a secret that he wanted to share with no one else. I found that very uncomfortable and continually backed-up. We managed to put him on a bed, switched off the light, closed the door and retired. For a long time thereafter, until I went to sleep, I could hear the hissing and huffing of uncle Ponnu's snore from the room.

Uncle Ponnu and his unique relationship with alcohol continued for the rest of his life. My Mother tried hard to get him to stop drinking, but that was a hopeless effort. In fact, all of us wanted to help him to get rid of alcohol but we couldn't because he wouldn't listen to any of us. Years passed and he lost his personality. The more he drank the sicker he got. It became impossible for him to continue with the job at the bus company. He had to remain at home totally depending on my mother for everything he needed. One day he suffered a stroke and became a cripple.

When I came home from Delhi on leave, I was appalled to find uncle Ponnu in a miserable condition. He couldn't stand up and walk, only crawl on the ground. He couldn't speak, only blabber. His hands had lost their power. He had to be spoon-fed. His body had shrunk beyond recognition. He looked like a wounded bird that had lost its wings. He looked at me\; his eyes filled with tears and attempted to say something but failed. I held his hand and cried. I returned to Delhi with this image of uncle Ponnu uppermost in my mind. Barely a few weeks later, one day, I received the devastating news that uncle Ponnu had passed away.

© T.S. Nagarajan 2010

Add new comment