Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Living through the 1947 Partition of Bengal -2

Category:

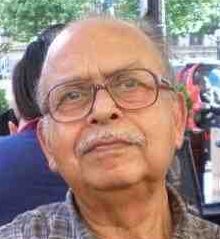

Tapas Sen was born in Kolkata (1934), and brought up in what now constitutes Bangladesh. He migrated to India in 1948, and joined the National Defence Academy in January 1950. He was commissioned as a fighter pilot into the Indian Air Force on 1 April 1953, from where he retired in 1986 in the rank of an Air Commodore. He now leads an active life, travelling widely and writing occasionally.

Editor's note: This article originally appeared on Air Commodore Sen's blog TKS' Tales. It is reproduced here with the author's permission. This is Part 2. Please read Part 1 first.

September 1947 - changes in the environment

As the days went by there were subtle changes in the environment that could be felt, though not fully defined. One was an erosion of identity. Slowly, all the Hindu government servants were transferred out. Most of them went off to ‘India'! The officers in the administration, judiciary and police became new faces, and most of them were not even Bengali speaking.

I had grown up with the feeling that everyone who mattered in the town knew my father, and held him in respect. All of a sudden, over just a few months, the town was being run by people whom we did not know, and who did not care who we were. It was all very subtle, this progressive loss of social recognition. No one was outwardly rude or crass, but we missed the smile while crossing the road or the nod of the head at the market place. It is strange that such minor changes mattered emotionally, but it did.

Problems arise

The number of migrants from Jessore to ‘India' progressively increased, and it forced a discussion of the subject at home. By the time Durga Puja came and went (in October 1947), a number of people we had known well had taken the decision to shift. Often, these shifts were not clear-cut migrations. Perhaps a son will get admitted to a college in Kolkata or pick up a job there\; perhaps the mother or the father will go with the son for a long stay to ‘settle him down' while the rest of the family remained at Jessore.

But silently, the process of finding a foothold on the other side of the border became a recognizable pastime of the townsfolk.

Baba was not moved by this. He made no attempt even to think about a transfer of residence. All our property was now in Pakistan. The house and the orchard at Jessore, the house and over 100 acres of agricultural land at Pabna, the share of ancestral land in Barisal town and in the zamindari in the countryside there were all situated in this newly formed country. We were clearly in limbo as emotional Indians trapped in a country we did not politically relate to.

During the Puja holidays, Didi Chitra (my eldest sister) came back from Kolkata to be with us for a few days from her B. Ed. studies at the David Hare Training College. One day, she decided to go to her old school and look up her friends. (She had been working as a teacher in her old school for a few months before she had gone away to complete her B Ed). My second sister, Monidi, had gone along with her to the school.

On their way back home from the school, they faced a problem that upset them very much. As they travelled in a cycle rickshaw, a few Muslim boys tailgated their vehicle on cycles and passed lewd remarks. When the rickshaw pulled into a Hindu neighbourhood, the boys went away. This incident was followed by another incident where a group of boys surrounded Monidi, and photographed her with hand held cameras as she walked to her tuition class.

Such incidents created a feeling of insecurity. When these incidents were brought to Baba's notice, he shook his head, and wondered aloud for the first time whether we might have to migrate to retain our honour in our own eyes. However, that seemed to be merely a transitory reflection\; Baba remained steadfast on not moving out.

His determination was soon tested. He was a registered medical examiner with the Hindustan Life Insurance Company. After August 1947, its business in Jessore decreased markedly. One day, its main agent for the area visited Baba, and agreed that the business was not running well in Pakistan.

The agent informed Baba that the Hindustan Group was diversifying its business into land development. It had managed to acquire a large contiguous area near the mint at Kolkata that was being used as a military camp. They were in the process of laying out roads and drainage and a new township called ‘New Alipore' would spring up there. He informed Baba that as an empanelled doctor with the Hindustan Group he would be entitled to allotment of two plots of land, if he applied immediately.

The agent also told Baba that since a lot of Muslim families of Kolkata were seeking investments in landed property in Pakistan, it would be easy for him to find the money for the proposed plots in New Alipore by putting our Jessore house up for sale. Its current ‘requisitioned' status might not materially affect the sale. Baba just laughed him off. He was not selling his property and he was not moving out!

This confident posturing about not moving out was jolted badly a few weeks later. We found out that Dr Jibon Ratan Dhar, our influential neighbour and a close family friend, had decided to move out. Jibon Babu was a very active politician in the Congress organisation. He was the incumbent president of the District Congress Committee of Jessore. Apparently, he was given to understand that if he decided to migrate he might be offered a cabinet post by the Government of West Bengal. He did migrate and did become a minister in West Bengal. His movement away robbed a lot of confidence and security from the emotions of those who had decided to stay back at Jessore.

A month or two later, we got the news that Baba's oldest cousin, Sri Surendra Nath Sen (my Boro Jethamoshai), was moving out from the ancestral property at Barisal. He was getting old, not keeping well, his children were already in Kolkata, and he needed attention from his children. Some ‘reasonable' settlement was available for the ancestral property. The logic for the move was indisputable.

We went and saw him at Jessore railway station as he passed through on the Barisal Express. Baba and Jethamoshai had a long chat as the train waited. Jethamoshai handed over some money to Baba as his share of the ‘settlement money' received from the sale of tha ancestral property. And that was that.

However, even this event did not cause Baba to consider migration.

By the end of the year, there was a new Sub Divisional Officer of Jessore. We were pleasantly surprised to find that the new incumbent was our own ‘Saiyed Mamu'. Saiyed Mamu (I did not know him by any other name) was a classmate of my second mamu, whom we called Ranga Mama. When my Dadu (Nanaji / Maternal Grand Father) was posted at Barisal, Saiyed Mamu had become close to Ranga Mama and his entire family to the extent that he spent his summer holiday in 1942 in my Mama Badi (mother's family home) with Ranga Mama. Ma and us children had gone to Barisal spend our summer holidays. We therefore knew Saiyed Mamu rather well.

Saiyed Mamu had just joined the Provincial Civil Service and was posted as the SDO of Jessore Sadar as his first appointment. Promptly after his arrival in the town, Saiyed Mamu to pay his respects to Baba and Ma and assured us of all help needed by us. He was sorry to see us out of our own house, but that had happened before his arrival.

Education concerns

By the end of December 1947, there was news (or just rumours) that the University of Calcutta had decided that for the academic year commencing April 1948, colleges under the university would not recognize school final certificates issued by the school board at Dhaka. This created a big problem for me. The degree college (Michael Madhusudan College) at Jessore offered only humanities. The nearest College from Jessore that offered graduation in science was at Daulatpur in the neighbouring Khulna district, some twenty miles away.

However, one fine morning, the whole staff and students of Daulatpur College had migrated en-mass to India, and had setup a new institution at Barasat across the border. The college at Daulatpur had become a set of empty buildings. That left only the colleges at Dhaka or Chittagong where I could go for my graduation after school.

My Matriculation examination was scheduled for March 1948. I had no time to dilly-dally. I had no intention of jeopardising my future. I intended to join the Bengal College of Engineering at Shibpur (near Kolkata) just like Dadu, my maternal grandfather, and my immediate role model Mr K N Ghosh. To get into the Shibpur College, I just had to do my intermediate science under the University of Calcutta!

Many of my classmates were migrating to schools across the border. With Baba's permission, I sought a certificate of transfer from my school. As I reached the school office with the application for a transfer certificate in my hand, I ran into Sri Amrit Lal Mukherjee, the retired head master who was then functioning as a mentor and a consultant to the school. Everyone referred to him as the ‘Old Head Sir'.

What is that in your hand? He wanted to know. When I told him about the purpose of my visit, it was clear that he did not like it. He pierced me with his steely gaze, and asked me whether my family was migrating to India. I had to tell him that I did not know about any such plan. He told me to go and ask my father about his query. If you are migrating, come back to me. If you are staying here, and want to sit for your matriculation for Calcutta, then go and appear as a private candidate\; I shall not give you a transfer.

I was thunder-struck. I did not know the reason for his outburst and did not know what I was supposed to do. I certainly wanted to appear for my matriculation under the University of Calcutta, but I did not wish to do so as a private candidate. Traditionally, private candidates had a harder time getting into a good college.

I came back home and narrated the story as it had unfolded. I had expected Baba to confirm his disinclination to migrate, and then advise me on how I should proceed under the circumstances.

To my utter surprise, I found Baba to be indecisive. He said he would go and talk to Amrit Mastermoshai, and dropped the subject. Next day, Baba went to my school with me and marched into the Old Head's office. I was told to wait outside. A little later Mr Sarvajna the current Head Master also marched in and joined the discussion.

About an hour later, I was called in. The application in my hand was signed and I was asked to collect the Transfer Certificate (TC) from the office clerk. The discussion in the Old Head's office carried on for a long time. By the time Baba came out, the TC was in my hand.

After we reached home, I asked Baba what the long discussion was about. Had he told the school authorities that we all shall migrate? No, Baba said. It was not something that could be decided so simply. But I could see that Baba was deep in thought, and visibly disturbed.

That evening, Mr Ghosh strolled down to our house. Our new abode was very close to his house. Over tea and roasted peanuts, a lot of discussions took place. Mr Ghosh was a founder member of the committee that ran the newly established M M College. He bemoaned the fact that many of the teaching staff and even non-teaching staff of the college had started migrating out. It would be difficult in the short run to find enough teachers to run the college efficiently.

The matter of my moving out of my school also came up. The elders seriously debated whether, after I got into a college in Kolkata, and Didi Chitra finished her B. Ed. and got a job in Kolkata, it would be worth their while for Baba and Ma to stick around at Jessore. My second sister, my Monidi, was in any case doing her Inter Arts privately. If Baba and Ma went away to Kolkata, she would just go along.

The idea that the family might decide to move out of Pakistan, if not immediately then perhaps some time soon, was now recognized and discussed openly.

Early 1948 - indications of a move to India

Saiyed Mamu had made it a habit to drop in at home every once in a while to spend some time with us. He would come straight from his office, have a cup of tea, chit-chat and go back, sometimes after sharing a plate for dinner. That was before his wife came down to join him. Even after his wife had come and set up his home, he kept up his routine visits with regularity.

One day sometime in February 1948, he had a closed-door discussion with Baba and Ma. The children were excluded from the discussion, so I do not know what transpired exactly. However, at the end of this discussion, my parents were quite disturbed. Follow-up discussion continued between Baba and Ma that night and for the succeeding days. It became clear to us that the discussion was about a decision to migrate to India. A decision was yet to crystallize.

A lot of factors affected this process of decision-making. There was a general decline of Baba's health over the last few months of 1947, coupled with a decline in his earnings as a practicing doctor over the same period. It was likely that Didi Chitra would get a teaching job in a school in Kolkata. It was important for me to go Kolkata for my intermediate science.

There were some other factors. Didi Chitra was then close to 20 years of age, and Monidi was past 17. Both of them were almost ‘marriageable'. It was evident that the bulk of young men from our community would be on the other side of the border. Even for the families who had decided to stay back in Pakistan, the younger people were looking for and finding jobs more in India than in East Pakistan.

On the other hand, we had no establishment in India that we could march into. Baba had invested all his liquid assets to purchase land in 1944 at Pabna. Now, all that land had become unproductive, as we had moved back to Jessore. If we now went away to India, it was more than likely that we would lose control of our houses and lands in Jessore as well as Pabna for ever. It was indeed a tough call.

At 13 years of age, I was not really privy to my parents' thought processes. We, the children, were benumbed with the unknown and could only hang on to the unshakeable faith on the ability and sagacity of our parents as our emotional support.

I have deliberately not used the word fear\; for unknown reason, none of us children was ‘afraid' of the future.

March 1948 - the move

A couple of weeks later, a letter arrived from Baba's cousin Sri Hemendra Nath Sen. He was then the second senior most in Baba's generation within our extended joint family. He had settled down at Sylhet, where he was running a business of limestone mining, extraction and marketing. His oldest daughter was getting married. The marriage ceremony would be held at Kolkata. He expected all of us to come to Kolkata for the occasion.

He was also in the process of winding up his business. If all went well, his family would not return after the marriage to Sylhet. His second daughter was doing her graduation as a private candidate. His son, who was of my age group, was about to appear for his matriculation examination under the University of Calcutta. His youngest daughter was very young. So, he had all intentions of converting this journey to Kolkata into a migration.

He had rented a large house on SR Das Road, which was a good residential locality. The house was big enough to accommodate his own children, and the seven of us (Baba, Ma, four children and Thakuma, my grandmother).

This invitation, coming soon after the long session with Saiyed Mamu, seemed to act as a catalyst and caused a crystallization of a decision to migrate in Baba's mind.

On 28th of March 1948, we left Jessore for Kolkata. We took with us with all our mobile assets that could fit into two three-ton trucks. A new journey in my life began.

Epilogue

Today, sixty-three years later, with clear hindsight and the wisdom gathered over this time, I am still unable to untangle the thought process of my parents and their friends and relatives at that time. What exactly caused them to abandon all their assets and their security, and migrate to a very uncertain future?

Let me state very clearly that at Jessore we were under no imminent threat to our lives and property. We were a well-established stable secure elite family of the town. It was clear that would bring us to an unfamiliar environment, where socially and economically we would be far more challenged than we were at Jessore.

And yet, our sober intellectual mature stable parental generation decided to migrate into potential loss of assets and social standing. What was their main consideration?

I think the main threat to them was the psychological uncertainty of the time. Things around us had changed so rapidly in the few preceding years that it was difficult to predict what would happen in the next decade. India, and its national leadership over the preceding fifty years, had constructed a recognizable post-independence plan. We had debated over the types of governance we wanted and the type of social reforms we desired. India had managed to create a constituent assembly which, much to the chagrin of the British masters, had declared its intention to acknowledge itself and behave as a sovereign entity.

In that moment of history, we were in the midst of a storm. Visibility was poor and winds uncertain. Thunder-strike rain and hail were imminent matters of chance. But we at least felt a sense of direction with the concept of India, of steps we knew existed even if we did not see them yet.

With the concept of Pakistan, this sense of direction was missing. None of the politicians clamouring for Pakistan ever talked of the social and economic goals for which they wanted a piece of land. All we were told was that it would be a ‘Muslim country'. We were also told repeatedly that in Islam a non-Muslim is a second rate person, with less rights and liberties than a Muslim.

We were not at all sure that Pakistan with such an ambiguous social philosophy would succeed in creating a successful nation state in the 20th century. And we were not sure whether, if the experiment of Pakistan indeed succeeded, there would be any social future for us the ‘non-Muslims' or Kaffirs to become its proud citizen.

I am glad our parents had the courage and the foresight to take the correct decision in the face of the existent risks for their immediate future.

______________________________________

© Tapas Kumar Sen 2014

Comments

Add new comment