Latest Contributions

My Early Years - 3

Category:

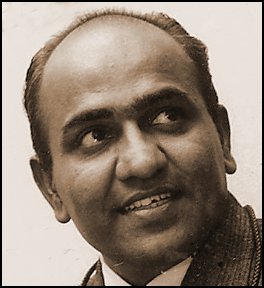

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

Editor's note: This story is reproduced, with permission, from Mr. Nagarajan's second not-for-sale book of his memories, Self-Portrait: The Story of My life, 2012. This website has several excerpts from his first not-for-sale book A Pearl of Water on a Lotus Leaf &\; Other Memories, 2010.

This is the third of three sequential stories about his early years. The first story is available here and the second story is available here.

Gated Home

The college I had to join, Yuvaraja's College, had been upgraded as a Science degree college and was renamed as First Grade College. By the time I got ready for a degree course, we had shifted residence from Chamaraja Mohalla to a new extension called Saraswatipurm, which had come up behind the Law Courts. A bigger place was needed. The family had grown large and the house was crowded. Satyan and I found a house owned by a doctor, known to father, on a monthly rent of fifty rupees. It was a small bungalow on a large plot of land with a compound and a wooden wicket gate. There were three small bedrooms, a large hall, a kitchen, store and a bath. The lavatory, again very small, was located behind the house\; next to it was the utility area for cleaning vessels and washing clothes. There was a solitary drumstick tree with countless drumsticks hanging from its branches. The vacant space around the house was so much that we could play cricket within the compound.

Saraswatipuram was a nice area to live with cultured and educated neighbours. Quickly, I struck friendship with a number of boys of my age in the locality\; some of them had also passed their 12th standard examination from the First Grade College. That was the time when most parents wanted their children to either become engineers or doctors. There was a big rush for seats in those colleges. The colleges demanded huge sums of money for admission. A new engineering college had just come up in the city called The National Institute of Engineering (NIE). I wanted to take up engineering. I broached the matter with father. He rejected my proposal outright saying that he couldn't afford to pay for an expensive course like engineering, and suggested that I continue in the First Grade College and get a B.Sc. degree. Most of my friends like Sampth, Rajashekar, Nagaraja, Vrishabhendra, were able to join NIE. Lakshminarasimha, Shankarappa and I joined the First Grade College for a two-year degree course

I liked the life in the new home. My mother conducted all the household affairs efficiently and with a touch of diplomacy. I was very close to her and admired the way she presided over the family. She would do (or get done) everything at home with clockwork precision. She was very God-fearing. Her routine would never change. Lunch would begin only after she had gone to the backyard with a morsel of cooked rice in hand and called the crows in her squeaky voice "Kaa, Kaa". The birds would fly in promptly and wait for her to feed them. It was only after the crows had eaten, lunch would be served. She never missed this ritual.

Practical Joke

There was another routine on which she was very keen. A beggar would arrive in front of the gate, late at night, after everyone had finished dinner, singing a song in Kannada, "Oh, Shivane Bhawagantha, Dharumaare Taayi Tandavva....", appealing to all mothers and sisters to do dharma in the name of Lord Shiva. In the quiet of the night, this song would be heard in the entire neighbourhood. With the head covered with a sheet, he would carry a sling bag and stop in front of the house for alms. His arrival would generally coincide with all the lights at home going off for a few seconds indicating the time: 9 pm. (Those days not every home had a wall clock. The electricity office in Mysore would switch off power for a few seconds every night at that hour to indicate the exact time to the residents.) As soon as mother heard the song, moments after the lights had blinked, she would run to the dimly lit house front with a bowl full of leftover food and empty it into the beggar's bag, and quickly walk back. She had done this for some years. The ritual had almost become an involuntary action.

One night, moments before the lights blinked and mother heard the song, I covered myself in a sheet to look like the beggar, jumped the compound at the back and walked up to the house front singing the same song. Lo! And behold! My mother came out running with the bowl full of food and quickly emptied into the bag I carried.

I walked forward singing the song, jumped the wall again and was back in the house in a jiffy. A few minutes later, promptly the lights blinked at 9 pm, and the beggar showed up at the gate singing the song. A confused mother hastily commented in Tamil, "What has happened to this bloke? He has begun showing up twice!" and looked at me. Unable to hold myself, I burst into a guffaw and let the cat out of the bag.

By the time we settled in Saraswatipuram, father had retired from government service and Satyan had returned to Mysore after quitting his two jobs: in Bangalore with "Deccan Herald" as its staff photographer and, a little later, as Feature Writer to The Illustrated Weekly of India in Bombay. He had decided to work as a freelance photojournalist. He was also married and had opted to live separately in the Model House Block, in walking distance from our new home. Though Satyan lived separately with his wife and son, the family was still large. Two of my elder sisters had been married, but one of them, Subbulakshmi (the first daughter), had returned home because her marriage had failed. I was too young to understand why. My father, who suffered from much diffidence, chose not to take up the matter with his son-in-law and his parents. He welcomed her into the family. He didn't think of her future at all. She was not urged to study further or trained in some institution for pursuing a vocation. She became a helping hand to mother and eventually a permanent attachment to the family. My grandmother had chosen to live with her daughter after she had become a widow\; and my mother's younger brother, uncle Ponnu, also lived with us. There were too many people in the house.

Though it was a crowded home, I was able to derive much happiness from the special relationships I had built within it. I was very close to my grandmother. Like most grandmas, she was a remarkable person.I admired the way she lived in a home which did not belong to her. She conducted herself as an invisible member of the family. We called her "Ammamma", meaning mother's mother.

Grandmother's Pet

The Kitchen was my grandmother's territory. Getting the lunch ready was her portfolio. At dawn she would enter the kitchen, fresh from her bath, wearing a beige coloured sari (washed and dried by her the previous day) and anoint her forehead with grey stripes of vibhooti, light a lamp and drink a little water from a tumbler with a sprig of tulsi leaves in it. She was a very meticulous cook. She would use only stone containers called kalchettis for preparing most of the dishes. Rice was cooked in a big brass vessel smeared with ash on the outer surface for easy cleaning of the black soot that would get deposited on it during cooking on an old-fashioned earthen oven using firewood. There was a stone pestle and mortar to grind fresh spices for curries. Her kitchen always tempted us with its enticing mixture of smells.

She observed all the traditional customs and regulations prescribed for a Brahmin widow. In the past a widow was not allowed to remarry. She had to shave her head and wear a simple beige-coloured sari (specially woven for widows using natural banana fibre) and cover the top of her head with the pallu of her sari. She was also to give up putting a bindi on her forehead. Basically, widows had to lead a very austere life with little joy. Mercifully, over the years, all these practices have gradually fallen by the wayside.

Her attire and the shaven head didn't appear odd to me. She looked like all other grandmas. She always made it a point to save a small portion of her evening palaharam for me, which was always some simple tiffin not made of rice. I used to wait for this tasty bite every evening. She slept at night on a simple mattress at one end of the hall. Before I went to sleep, it was my practice to lie down next to her for a while sharing her thin pillow. She would tell me little stories while she kept her fingers busy stroking my bushy hair to remove any sand or dirt that might have settled while playing.

I must mention here about a special assignment I had to do for my grandmother every month about which she felt very embarrassed. A barber had to come home to tonsure her head. The job had to be done in the darkness before dawn giving her enough time to have her bath and get ready before the house woke up. She would tell me in advance about the auspicious day on which this had to be done and definitely remind me the night before while she stroked my hair before I went to sleep.

I would get up very early on that day, ahead of my father, who was the first to wake up, open the door and quietly vanish into the darkness riding my father's bicycle towards the barber's home, some distance away\; and peddle back accompanied by the barber with his tool kit. I had devised this arrangement to make sure that the barber arrived on time without fail and completed the job. Over the years, the barber and I had become good friends and, as a result, this special job had almost become a routine. Apart from me, perhaps only a few had seen my grandmother sitting on a wooden plank facing the barber in the backyard next to the water tap. I suspect, they deliberately avoided any discussion on it. I was aware that my grandmother was deeply grateful to me for doing this delicate job without any murmur. This had certainly built a special chord of affection and love between us. I am very clear in my mind that I was closer to her than to my mother and remained so till she breathed her last with her head on my lap at a ripe old age.

My mother loved her younger brother whom she called "Ponnu" (meaning gold). At a time when money was scarce to run the house, he proved himself an asset to the family. But her golden brother had a huge weakness. He loved the bottle and was given to drinking. Often, he created much embarrassment to everyone, especially to my father, because of this weakness. Uncle Ponnu, a chronic bachelor, did not have much education and was physically challenged. He was born with clubbed hands and had a somewhat fierce exterior. He worked as a bus conductor for a city transport company. On some days, when he returned from work late at night tottering and almost passed out, my father would lose his cool and shout at my mother. He would rule that she should see her brother was banished from the house the next morning. But, nothing would happen. The following day Uncle Ponnu would go to work as usual, lovingly seen off by his sister. My mother couldn't afford to send him away. He helped her run the family. My brothers and I were very fond of him because of all the goodies he brought for us. We accepted him with all his faults.

My father didn't interfere in anything mother did. He was by nature an escapist who preferred to run away from problems. He was a figurehead who moved about the house quietly and lived in a world of his own. He enjoyed smoking. He bought one cigarette at a time from the corner shop in order to exercise some degree of control on the number of cigarettes he smoked in a day. He never smoked within the house but preferred to wander within the compound smoking his cigarette. He was a very simple soul with almost no ambitions. He had a bicycle on which he would peddle every evening to see his friend, a veterinary doctor, who lived not far away.

I gelled well with my new friends in Saraswatipuram, Sampath, Raghavachar, Rajashekara, Nanjundaswamy, Vrishabhendra, Nagaraj and Lakshminarasimha lived very near one another. Only Shankarappa lived a little far away on 100-ft Road. Somehow Rajashekara and I came close to each other and spent a lot of time together. All of us met at Rajashekar's place every evening and played badminton in the open space across the road. I was not much of a player. Sports didn't excite me, though in later years I liked watching football and cricket. I never played any game. The only time I remember playing Cricket on the University Oval Ground was for an inter-class tournament, more to please our Captain Puttaraj Urs. I remember when my turn to bat came, I walked up to the pitch stylishly and took position. A fast bowler was in action. When the first ball came towards me like a rocket, all that I did was to run away from the crease to save myself. The wickets went flying. I walked back to the pavilion after scoring a zero and lowering my head amidst taunting shouts from the crowd.

It was our routine to walk up to the Five Lights Circle (later named Ramaswamy Circle) after the badminton session in the evening, and sit under the lights for a chat. None of us had much money. We pooled whatever we had either to buy groundnuts or, on days we had more to spare, go to a hotel to help ourselves to shared ‘set dosas' (a set of three small dosas in a plate done with very little oil along with a vegetable stew called Saagu) and "one by two coffee" (a cup of coffee made into two equal parts and served in two tiny cups). The hotel we preferred was called "Nameless" known for its high quality and delicious items. It was, in fact, the most famous restaurant in town. The hotel functioned on its big reputation for quality. The owner, an Ashtagram Iyer, felt that no name was necessary for his enterprise, but the clients named it "Nameless". Among my friends, I was the poorest. My father never gave me any pocket money. Uncle Ponnu was the only source of money for me. If my brother Jagga and I met him at the bus stand, when he would arrive from his bus trip, he not only gave us some cash but also took us to the Udupi hotel for Masala Dosa and coffee. On these evenings I had to miss being with my friends.

On some evenings, especially on holidays, instead of sitting under the Five Lights, we walked down 100-ft Road, beyond the Palace Offices, up to Nanjangud road. Here we sat on a stone bench under a tree. It was a good change. This was the route the Maharaja, Sri Jayachamaraja Wodeyar, sometimes took, possibly for an evening drive in his limousine. When we sighted the car at a distance, all of us stood up and saluted the Maharaja as the car passed in front. The Maharaja invariably turned towards us and returned the greeting. This chance encounter with the Royalty was an event of celebration.

Mysore Gentleman

My college was within walking distance from the home. I found studying for a simple science degree was no big deal. Sometimes, I felt that I was merely going through a formality. One day in the college, I heard that Iravatha, Mysore's celebrated elephant, was no more. He was a friend of our family. It was impossible to believe that the city's most loved one lay dead in the stables at the palace. My friend and I bunked the class and peddled fast on our bicycles towards the palace where a huge crowd had already gathered. We found Iravatha, lay stretched on the ground, grand and dignified. I felt as though a very dear friend had died. Back home, a lump in the throat made me speechless. I went to my friend's room, where we used to do "combined study", to spend the night. I couldn't sleep and so I decided to pour out my grief in words on a sheet of paper. The result: A Mysore Gentleman Passes Away, my first article ever written.

The following morning was spent in hunting for a picture of Iravatha to accompany the text. I went from studio to studio asking for one. No one was willing to help, perhaps thinking that I would make a fortune by publishing it. Finally, the city's then famous photographic studio, Raj &\; Bothers, came to my rescue and helped me with an unsatisfactory picture of the elephant. I mailed the article and the picture to the Editor of the Illustrated Weekly of India explaining my inability to provide a better photograph. A few weeks later, the editor, an Irishman, sent me a copy of the magazine with my story, along with a cheque and a note urging me to take to the camera "if I had ambitions of making a success of my career as a journalist." Looking back, no doubt, the editor was right.

The two years in the college went without much effort on my part. A day before the Convocation, I went to the market to get the prescribed dress: white pants, a black coat and a turban, on hire to wear for the Convocation. I went through the ceremony without much excitement. I knew the degree meant nothing for a job and I had to do something more to carve out a good career for myself. With nothing happening on the job front, I even went through a highly depressing phase. I felt that I was a good-for-nothing fellow. May be, the best I could do was to either become a bus driver or, if I fail to qualify, become a waiter in a hotel. I spent most of my time simply remaining at home or went out in the evenings with my friends, most of whom were busy qualifying themselves as engineers. My future appeared unfocussed. But like a true Mysorean, I waited patiently to see the sunrise in my life.

Original Mysorean

Life in the city had a certain timelessness. A Mysorean invariably appeared lethargic\; gave you the impression that he had all the time in the world. He was never in a hurry. One could see groups of people just sitting here and there, doing nothing. If two friends met accidentally on the road, they chatted endlessly. Walkers with unopened umbrellas dotted the city's thoroughfares at any time of the day. But Mysoreans, if they chose to do something, they excelled in it, invariably\; for example, even in a not so extraordinary activity like taking a walk in the evening. Walking was an admired ritual\; for most elders it was a kind of unfettered release.

It was a folly to underestimate the Mysorean, who generally appeared contemplative and self-effacing. It would take some time to realise his wit and wisdom, which unfolded slowly and unobtrusively-"Majjigeyolagina Benne Andadi"- as the butter emerged magically from buttermilk.

There was an unintended artistic expression by the people even in seemingly ordinary matters. In the Devaraja Market, the heady aroma of Mysore Mallige welcomed you. (Mysore Mallige is a unique variety of Jasmine flower (Jasminum grandiflorum), patronized by the Wodeyar kings of Mysore, and grown in and around the city of Mysore. Famous the world over for its lingering fragrance, the flower has been patented. There are a number of varieties of Jasmine (called by different names in the country as Mogra, Motia, Chameli, Malli Poo etc.) but this Mysore variety is considered special. The flower has inspired a famous poet, K.S. Narasimhaswamy, to write a very famous collection of poems called Mysore Mallige, which is considered as among the best literary works in Kannada. Like the famed Filter Coffee, the Mysorean looks at the flower as a pride of Mysore.) There was order and method in the manner in which the City's famous jasmine was sold in the market. The flowers were artistically knotted on threads of unending lengths and laid softly in spirals, one above the other, in wicker baskets. Next to the flower sellers were women, bright and beautiful, with a twinkle in their eyes and a mischievous smile, selling Mysore's betel leaves, which they held admirably in their hands like little green fans. The vegetable stalls were a visual treat. The tender brinjals were arranged beautifully in clusters on wet granite slabs, like artistic installations in a gallery.

To the Mysorean, Coffee was booze. He was very particular about its taste and temperature. A guest sitting in the hall had to savour its elevating aroma wafting from the kitchen, well before the housewife walked towards him with a tumblerful. Talking about coffee was also a convenient opening gambit for most casual chats. It was not amusing if instead of saying ‘good evening' to you when meeting an acquaintance on the road, to say ‘coffee aayithe', which meant "Have you had your Coffee?" It did not matter even if it was not coffee time.

The word change was something a Mysorean was averse to. The greatest tribute that he could bestow was to describe you as a nidhanasta. Though this literally meant a "slow person", it merely referred to you as a calm and composed person, not given to fits of temper. Another bigger tribute was to refer to you as Manushya Swalpanu Change Aagilla Haage Iddane, which meant that despite a lapse of a long period of time, one had not changed at all. The idea was to appreciate you for not throwing your weight about in spite of laudable achievements. The Mysorean liked everything around him, including his city, to remain exactly as it had been for years.

I went to Mysore, after living in Delhi for over three decades in order to rediscover my home town. But a city in ruins welcomed me. The unchanging Mysore had indeed changed. The brilliance of Gulmohur on the thoroughfares was missing. The nooks and corners, of which I had fond memories, were now holding heaps of filth and garbage. There was dilapidation everywhere. The aged buildings were crumbling. The once handsome city looked somewhat idiotic and totally neglected. The city in which my friends and I, as college students, had once counted 9,000 or more trees, looked barren, with most of them being cut for various reasons. Looking at my home town after a long gap of time, I could understand the process of decay which created historical ruins. I found the city dying. Most reluctantly, I settled in Bangalore.

© T.S. Nagarajan 2012

Add new comment