Latest Contributions

No railway bridge over the Brahmaputra

Category:

Kenneth Hugh Staynor was born at Madhupur on 16 September 1927. In 1929, his family went to the United Kingdom, and returned to India in 1931 to Kurseong, where his father was a teacher, and later Headmaster, at Victoria School. Kenneth was educated at St. Josephs College, Darjeeling, and St Mary's High School, Mount Abu. He left India in August 1951 for permanent residence in the UK to get into research and development in engineering, which was not available in India, and because his ancestral roots were in the UK. He lives in South Wales after retirement. His wife passed away in January 2010\; he has three sons, five grandsons, five granddaughters and one great granddaughter.

Editor's note: This is part of a chapter from Mr. Staynor's forthcoming book.

In 1947, one afternoon, I met a man in the lounge of the Calcutta Great Eastern Hotel.

He was drowning his sorrows with ‘Scotch on the rocks' after a journey from Bombay, en route to an appointment at some British mining or oil establishment in a place called Digboi in the extreme Northeast of Assam. He hailed from Aberdeen and had arrived at Bombay aboard the P&\;O ship Strathmore, but unfortunately he was not booked in the Air-Conditioned Coach on The Calcutta Mail.

It was May, which is perhaps the hottest month of the year in India, and he had not realised that the journey would take up all of forty hours or so, involving two nights on the train. Neither his Head office nor their branch in Bombay, had adequately briefed him about the journey which was something like 2,200 route miles in total. He told me he was booked on a train that left ‘Seeldar' station the next afternoon, and he had to change trains at some station or the other for another sleeper train and change again the next morning.

He had never left the shores of Britain before\; till then the longest train journey he had made was probably the journey from Aberdeen to Kings Cross in London and then to Tilbury Docks for his sailing to India. I don't know whether he was bemused, or bewildered by the long journey he had just completed from Bombay, but as the person I was due to meet at the hotel had not shown up and he looked such a sad and forlorn figure of a man, I decided to sit with him and see if I could cheer him up! He had a very strong Scottish accent and rolled his 'Rs' like a true Scot! But I managed to get the gist of what he had to say and after twenty minutes or so he almost had me rolling my ‘Rs' like a true Scot!

My favourite hobby of studying the Indian Bradshaw proved invaluable to this poor chap, and I decided to put the fellow in the true picture. I told him he would have to take the Assam Mail of the Bengal Assam Railway which left Sealdah Station (Pronounced See arl dar and not Seeldar) mid afternoon at about 2.30, arriving at a place called Parbatipur at 9.30pm. Then, he would have to change to a metre gauge train for the over-night journey to Amingong. I consoled him by informing him that, the Assam Mail had an excellent restaurant car for dinner. Then I brought on the sorrows again by telling him that in the morning at Amingong he would have to board a ferry to cross the Brahmaputra River, as there was no bridge across the river, to a place called Pandu. Breakfast could be taken on the ferry.

He would then have to board another metre gauge train, also called the Assam Mail, which had a restaurant car, for the last lap of his journey to Tinsukia and Digboi, which would be another twenty hours on the train. This meant that in all, he spent four nights on a train from Bombay to Tinsukia! He was going to have a great deal to write about in his first letter home, and I bet he had some nasty things to say about the Indian Railways! To me it would have been an adventure and a journey to be remembered!

Assam before the outbreak of World War Two was almost a forgotten province of India. Before Independence, and the splitting up of the Sub-Continent into India and Pakistan, Bengal was a vast province which included the cities of both Dacca and Chittagong\; indeed that whole area was referred to as East Bengal, and now comprises the biggest part of what today is known as Bangladesh.

Unlike as in the North West, invasion from the east was not considered a possibility by the British because of the almost impassable mountains of the Arakan Yomas, through which there were no recognised passes and covered by very dense tropical jungle. In any case to the east was Burma, which at the time, was part of the British Indian Empire. How wrong they were when the Japanese swept through South East Asia during World War Two, forcing Britain to virtually abandon Burma. This forced the British to change the province of Assam from being a non-entity, with a railway system laid to metre gauge and no bridge across the mighty Brahmaputra River, to the most strategic province in India, but found wanting with inadequate communications for supplies to the front.

The absence of a bridge over the Brahmaputra River also proved to be a delaying factor and major obstacle for vital supplies to the Arakan Front. A bridge over the Brahmaputra to the British seemed unnecessary before WW II, as to them, Assam had no strategic or commercial value. Assam's main resource was tea, which was easily transported by river steamer along the Brahmaputra to the various railheads along its course or could be shipped overseas via the port of Chittagong. The significance and importance of no bridge and the folly of a railway system constructed to metre gauge manifested itself only after the threat of invasion by the Japanese in WWII.

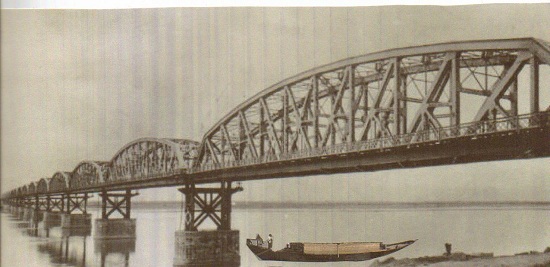

After the opening of the Hardinge Bridge in 1915 on the then Eastern Bengal Railway Main Line to Siliguri, which opened up through rail communications with the north of Bengal and the north bank of the Brahmaputra as far as Amingong, the British never embarked on any large scale bridge building projects in India.

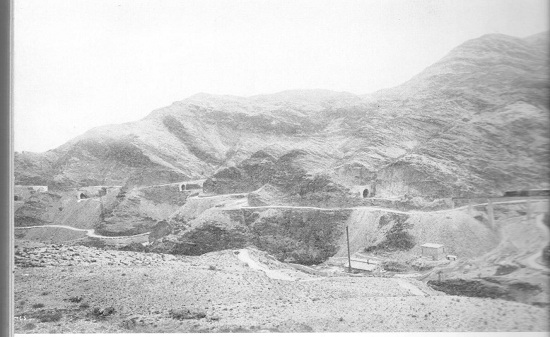

The British had an obsession with the idea that there was a threat of invasion by Russia through the Khyber Pass. So, the railway systems and communications in that area was of the highest standard. Even today the permanent way of the railway to Landi Khana through the Khyber Pass is maintained by Pakistan to the highest standard. But invasion of the Sub-Continent never came - even after the British left India, when the Russians occupied Afghanistan in an abortive effort of taking over the country! There has as yet, not been an invasion of the Sub-Continent through the passes in the North West since the Mogul invasion and occupation of India which lasted as long, if not longer, than the British occupation of the Sub-Continent. The British, nevertheless constructed a five foot six inch gauge railway to the highest standards and at a tremendous cost for defence, while no such expense on defence communications on India's Eastern border was considered necessary in Assam, which had to make do with a metre gauge railway system which was not even directly connected with rest of the Indian railway network except by ferry services across the Brahmaputra River.

I had a few more drinks with my dejected Scotsman before leaving him probably as downhearted and bewildered before our little chat. I can only hope he coped with the rest of his journey and the crossing of the Brahmaputra and that everything at Digboi was to his expectations\; after all we were just like ships that passed in the night!

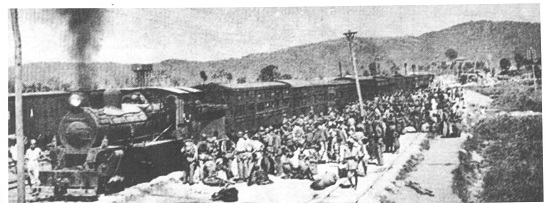

Wagons being shunted onto ferries at Amingong on the north bank of the Brahmaputra River for transhipment to Pandu on the south bank of the river. This is the crossing the man I met in the Great Eastern Hotel had to make on his way to Digboi. The absence of a bridge over the Brahmaputra caused delays of the supplies for the Arakan Front during World War Two.

American GIs waiting to board a troop train to the Arakan Front at Pandu on the south bank of the Brahmaputra River after the crossing from Amingong on the north bank.

The Hardinge Bridge across the Ganges between Biarama on the south bank and Paksey on the north bank which opened through rail communications between south and north Bengal and the north bank of the Brahmaputra River as far as Amingong. Opened in 1915 it was the last large scale bridge building project undertaken by the British in India.

A panoramic view of the Khyber Railway (North Western Railway) between Landi Kotal and Landi Khana on the Afghanistan Border. There were two invasions through the Khyber Pass during the Raj, both out of India into Afghanistan in abortive failed attempts by the British to make Afghanistan part of their British Indian Empire. In spite of the British concerns about and invasion of India through the Khyber Pass there has not been one since the Mogul invasion. The British, nevertheless constructed a five foot six inch gauge railway to the highest standards and at a tremendous cost for defence, while no such expense on defence communications on India's Eastern border was considered necessary in Assam which had to make do with a metre gauge railway system which was not even directly connected with rest of the Indian railway network except by ferry services across the Brahmaputra River.

_______________________________________________________________

© Ken Staynor 2013

Add new comment