Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

My memories of Britain’s long and tortured exit 1931-47

Category:

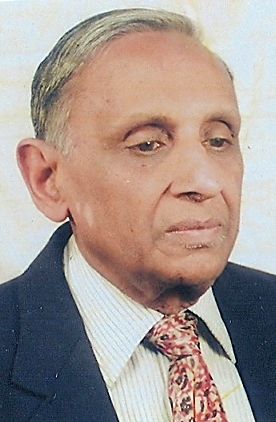

R. C. Mody has an M.A. in Economics and is a Certificated Associate of the Indian Institute of Bankers. He studied at Raj Rishi College (Alwar), Agra College (Agra), and Forman Christian College (Lahore). For over 35 years, he worked for the Reserve Bank of India, retiring as the head of an all-India department. He was also Principal of the RBI's Staff College. Now (in 2019), in his 93rd year, he is engaged in social work, reading, and writing. He lives in New Delhi with his wife. His email address is rameshcmody@gmail.com.

I was born in 1926. My memories of national and international events go back to 1931, when I first became aware that we, Indians, were a subject nation, ruled by a small island country named England. I learned that England lay across seven seas (saat samunder paar), and its inhabitants were called the British and they, unlike us, were white, gore. Skin colour was very important\; because they had fair skin, we felt that they were superior to us.

The British governed us through an officer called the Viceroy. About every five years, a new British Viceroy came to rule over us. He received a salary of Rs. 3 lakhs (one lakh = 100,000) a year, which made him the highest paid man in the world with a salary higher than that of the President of America. His palace in Delhi had 300 rooms. But he occupied this mansion for only about five and a half months every year. For the rest of the year, from late March to the end of September, Delhi was too hot for him, and he lived in Simla in the Himalayas, where he had another grand palace to live in. In 1931, the Viceroy was Lord Willingdon.

I lived in Alwar, a Princely State under the rule of an Indian Maharaja. We bowed to the Maharaja whenever he passed by in his elegant Rolls Royce car, or when he rode past on the back of an elephant, or in a chariot (indra viman). A retinue of attendants, themselves in cars or on trailing elephants, followed him. This grand Maharaja, I was at first surprised to hear, himself bowed before the Viceroy and his Lady.

At the same time, I became aware of a leader, Mahatma Gandhi, who, after becoming a barrister from London, engaged himself in a struggle to end British rule over India. The British often jailed him but were also afraid of him, and even respected him. Jawaharlal Nehru, I came to know, was another prominent leader. The only son of a rich Allahabad-based lawyer, the handsome Nehru went to school in England, and graduated from the University of Cambridge. Like Gandhi, he became a barrister in London. On return to India, instead of cashing in as a barrister, he joined the struggle for ending British rule over India. He too spent long stretches in jails.

The two leaders caught my imagination and earned my admiration when I was just 5-6 years old. Simultaneously, I became increasingly hostile to Lord Willingdon. Not least, his wife, Lady Willingdon, was vain. Maharajas flattered her with gifts of expensive ornaments in their effort to gain favours from her husband. She considered India a fiefdom of her family. She insisted on naming a road after her son Viscount Ratendone in the new capital city that the British built near the old capital in Delhi, originally constructed by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. After independence, the Government of India renamed the road Amrita Shergil Marg to honour that renowned Indian painter.

My political education

Because I lived in a Princely State, so-called "Indian India" (home to approximately one-fourth of all Indians), my knowledge of national developments and the freedom movement was only indirect through stories that filtered through. The excitement of the freedom movement was confined to areas under direct British rule ("British India").

However, like most educated residents of Princely States, my father was emotionally vested in the fight for India's freedom. He did his "intermediate" college in Agra, which was in British India. He then studied for his undergraduate degree in Allahabad, when it was the epicentre of the fight for India's freedom. Allahabad was special, in part, because it was the hometown of the Nehrus. In 1921, when Nehru was arrested for the first time, my father participated in the demonstrations that followed the arrest. (In 1959, Prime Minister Nehru remembered my father when they met in Delhi.) Father told us many stirring stories of his years in Allahabad. When the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII and still later Duke of Windsor) visited Allahabad in 1922, the street hoardings bluntly said, "No welcome to the Prince".

I entered school at the late age of ten. Abdul Shakoor Qureshi was notionally my history teacher. But Shakoor Sahib typically departed from the prescribed syllabus, and talked instead about matters that my father discussed at home. Gandhi, Nehru, and later Subhas Bose were his heroes.

Shakoor Sahib was a tall and handsome man. He dressed immaculately in a suit, and wore a necktie. I wondered later how he could afford such fine clothes. He drew only a low, two-figure salary, about Rs. 50 per month. Of course, those were days of global economic depression, so not only incomes, but also prices were low. Indeed, a person was fortunate to have a job.

During the 1937 holidays, Shakoor Sahib went to neighbouring U.P. (United Provinces, as it was called then) to observe the elections. These elections were held under very limited franchise under the Act of 1935, itself a product of the three Round Table Conference held between 1929 and 1933. Shakoor Sahib asked some voters whom they would vote for. Their reply invariably was "For Gandhi", even though Gandhi himself was not a candidate in any constituency.

Despite his admiration - even love - for Indian leaders, Shakoor Sahib migrated to Pakistan in 1947, at the time of independence. He felt he had little choice. In the hothouse of Alwar, his life could have become miserable if he had not converted to Hinduism. I have wondered ever since how Shakoor Sahib dealt with his love for Gandhi and Nehru after moving to Pakistan. I tried to trace him when I went to Lahore in 1999. However, I failed because most migrants from the Alwar region had drifted to Karachi, and I could not go there as my visa was restricted to Lahore.

Linlithgow stirs hope-and then dashes it

In March 1936, just about when I entered Shakoor Sahib's class, Lord Willingdon and his lady returned to England. For most Indians, it was good riddance. Linlithgow was the next Viceroy. He hailed from a Scottish aristocratic family (actions taken by an earlier Scotsman, Lord Dalhousie as Governor General, had caused the uprising of 1857).

Linlithgow seemed different. The word was that he, unlike Willingdon, would be a friend of India. He was known for his love of agriculture. It was he who took the early steps to implement the constitutional reforms prescribed in the Act of 1935. The reforms gave the Provinces some autonomy, as a result of which some of our leaders, earlier jailed by Willingdon, became Prime Ministers and Ministers in eight out the eleven Provinces. Suddenly, a person looking at India's map could see large areas governed by the Indian National Congress. The country, it seemed, had attained half the freedom for which it was struggling.

Then things changed. World War II broke out on September 1, 1939. On September 3, Linlithgow dragged India into the war as a belligerent power. He did so without consulting national leaders, causing great public resentment in India. The ruthless use of India's scarce resources for fighting a war that was not ours caused much anguish. Linlithgow met with Jinnah on September 4, believing that Jinnah was likely to offer more cooperation than the Congress leaders would in the war effort. Thus, Jinnah acquired greater bargaining power in his demand for Pakistan.

In October 1939, the Congress Ministries resigned. Their reason for doing so, many, including me, believed, were flimsy. The short-lived dream was over and we were back to direct British rule supported by their stooges, who were now put in charge of the Provinces.

Linlithgow's term as Viceroy was to end in March 1941 but British authorities extended it to maintain continuity during the early years of the war. The Hindustan Times, the leading daily newspaper, regularly printed cartoons by the well-known Shankar, who portrayed Linlithgow with his long chin as an arrogant and unaccountable figure who was hurting India's aspirations. Linlithgow evidently cared. The word was that he anxiously awaited Shankar's cartoons.

In March 1942, Sir Stafford Cripps, a minister in Winston Churchill's wartime coalition government, came to India with an offer of a bigger role for Indian leaders in governing the country. However, Gandhi spurned the offer, describing it is a "post-dated cheque on a crashing bank."

Jinnah's growing call for Pakistan

I left Alwar on July 12, 1942, arriving next day in Agra to begin m y undergraduate studies. I had visited Lahore and Delhi, but this was the first time I lived in British India. My entry into British India proved dramatic. On August 8, Indian National Congress leaders announced the Quit India movement. Mahatma Gandhi chose the word "quit," and it lit a spark of national consciousness.

The college authorities, fearing that the national fervour might cause disruption, asked us to vacate the hostels and go home. I returned to Alwar on August 12, exactly a month after I had come to Agra. I was not even 17 years old but was welcomed back in Alwar as a hero, as friends and families eagerly asked for details of the stirring events.

Linlithgow's popularity plummeted when he jailed Gandhi, Nehru, and many ex-Provincial Ministers.

The furore generated by the Quit India movement ebbed by October 1942, and I returned to Agra. The aspiration for freedom remained but with leaders in jail, the way forward seemed unclear\; job and business opportunities offered by the war distracted people.

In early 1943, we heard that Gandhiji, imprisoned in Agha Khan Palace in Poona (now Pune), had started a 21-day fast. The newspapers reported his condition every day. His physician, Dr. B.C. Roy, (regarded as India's top physician, who later became the Chief Minister of West Bengal), came all the way from Calcutta. After examining Gandhiji, he bluntly said, "If the fast is not immediately ended, it will be too late to save Gandhiji's life." But Gandhi didn't end the fast, and he was alive at the end of the 21st day. The country rejoiced. The inmates of my hostel wanted to illuminate the building. But our warden (a well-known botanist with the British honour of a Rai Bahadur) cautioned us. He feared that public celebration would annoy the authorities. He said that he was no less happy than the rest of us. Indeed, I recall him saying, "Every home is rejoicing, every heart is rejoicing, but we have to look after your future also."

My intense desire to see some of our leaders remained unfulfilled since they were all jailed within days of stepping foot in British India. However, in mid-1943, I saw the Muslim League leader M.A. Jinnah, who never went to jail and who wanted to carve out Pakistan as a separate country for Muslims. By profession he was a lawyer, and he was in Agra to defend a local contractor, a Hindu, who was accused of trying to bribe a British Colonel. The proceedings were conducted in the court of Agra's city magistrate, a Muslim. I saw Jinnah for a long stretch in the uncrowded courtroom, pleading for the contractor in a soft voice. I did not stay to hear the court's decision.

That evening I attended a public meeting that Jinnah addressed in an area called Baker Park. None of my hostel mates agreed to go with me. I was probably the only non-Muslim in the audience, though there might have been some non-Muslim press reporters. After starting in Urdu, Jinnah switched to English, apologising for his bad Urdu. In fact, his Urdu was not bad\; perhaps, it was straining him to talk in Urdu. The speech was full of zeal for Pakistan. Jinnah wanted all Muslims to support the demand for Pakistan.

In the press conference that followed, a journalist asked Jinnah why he had described Jawaharlal Nehru as a mashoor (famous) Hindu leader. Nehru, the journalist noted, was not much of a Hindu, being a professed agnostic. Jinnah coldly retorted, "An arch Brahmin, with a veneer of westernism." The meeting ended amidst shouts of Quaid-e-Azam Zindabad, Pakistan Zindabad (long live the Great Leader, long live Pakistan). The second slogan sounded odd in the city of Agra, which, by no chance, was going to be a part of Pakistan. Indeed, many of Agra's Muslims were lukewarm about Pakistan. Altaf Hussain, leader of Pakistan's MQM movement, which questions the wisdom of India's partition, was born to parents who only half-willingly migrated from Agra to Pakistan.

Linlithgow left in September of 1943, after seven and a half years as Viceroy, the longest period of any Viceroyalty because of his war-related extension. No tears were shed. The words "Tashreef le gaye" (a polite expression for "good riddance") expressed the relief people felt.

Wavell surprises, speeds up the march towards Independence

Linlithgow was succeeded by General Wavell, who had been Commander-in Chief (C-in-C) of Indian Armed Forces. The C-in-C was, in effect, the deputy to the Viceroy, and a member of the Viceroy's Executive Council (predecessor body to the present day Union Cabinet). The appointment, for the first time, of an Army General as Viceroy did not send happy signals. The British, it appeared, did not intend to hand over power in India to Indians in the near future.

But a few months after taking over as Viceroy, Wavell wondered why the old and enfeebled Gandhi was in jail. Gandhi's wife had recently died in prison, and if he also were to die in a British jail, it would bring disrepute to the British Government the world over. Wavell therefore recommended Gandhi's release. Even before final orders came from London, Wavell released Gandhi on May 5, 1944.

After his release from jail, Gandhi spent some time in Urli Kanchan, near Poona, for nature cure treatment. Then, in September 1944 (with other Congressmen still jailed in Ahmadnagar Fort), in consultation with Charkarvarti Rajgopalachari (a close friend and adviser who did not go to jail in 1942, and father-in-law of his son Devdas Gandhi), Gandhi made plans to meet Jinnah.

Jinnah hosted a series of meetings in his palatial house in Bombay's Malabar Hill (that house today lies unused and decaying with its ownership under dispute). On the first day of the talks, Jinnah, wearing a fine silk suit, came up to the porch to receive his guest but looked distinctly uncomfortable when the half-naked Gandhi embraced him. As was his practice, Gandhi carried his own food, although Jinnah would gladly have offered him chilled beer followed by a magnificent five-course lunch.

The Gandhi-Jinnah talks continued for about a week. Every day after they met, they exchanged letters summarizing their discussions (the Hindustan Times published the correspondence as a book, which I read during a train journey later that year). Respectfully addressing Jinnah as "Dear Quaid-e-Azam," Gandhi did not completely reject the idea of Pakistan. He suggested that partition should be a friendly decision reached by two loving brothers, and that a plebiscite be held in some of the areas. In any case, Gandhi proposed that they settle this matter after the British left. "Dear Mr. Gandhi," Jinnah wrote back, "I concede that you are a great leader with strong hold over Hindu India," implying that Gandhi could not lead Muslims. But following that brief pleasantry, Jinnah tersely dismissed the proposal of postponing partition planning to after independence. Doing so, he said, would be "putting the cart before the horse."

My vantage point now was Lahore. I moved to Lahore in September 1944, while the Gandhi-Jinnah talks were ongoing. My classes for M.A. in Economics were held in the University but every student had to be enrolled in one of the local colleges. I carried a letter from my Professor in Agra, Dr. Imdad Hussain (an alumnus of Government College Lahore) to Professor Sirajuddin of Government College Lahore, who retired decades later as Education Secretary to Government of Punjab, Pakistan. Professor Sirajuddin ensured that I was welcomed with open arms to Government College. However, when I chose Economics for my M.A., the University Professor of Economics wanted me to enrol at Forman Christian College (F.C.C.) (also a highly reputed College, alma mater earlier of I.K. Gujral, Prakash Singh Badal and later of General Parvez Musharraf). F.C.C. had a hostel, Ewing Hall, exclusively for post-graduate students and had (unlike any other hostel) a very well equipped library and reading room.

On my first morning in Lahore - with my hostel arrangements not yet finalized -I was asleep under a mosquito net on the sprawling lawns in the home of a family friend. The shouts of the daughter-in-law of the house woke me as she ran with morning edition of the Tribune in hand. Addressing her father in law, she cried, "Papaji, Papaji. Gandhi-Jinnah talks have failed."

Wavell, however, was uneasy with this limbo. Was it not time to respect the wishes of Indians and let them be governed by their own leaders? No earlier Viceroy had entertained such ideas or acted on them. Thus early in 1945, he decided to take a trip to London.

Wavell remained in England for several weeks, during which we had no idea what was he doing there. The war was still on, and Churchill, who was determined not to preside over the liquidation of British Empire, was still the Prime Minister of Britain. I remember suggesting to some friends that something was brewing. But the reply, understandably, was that the Viceroy was not going to be a Father Xmas. He could not be expected to return with "toffees and other goodies" for us, the waiting children.

Within hours of Wavell's return, the message spread that he would deliver an important broadcast that evening. We all gathered around the only radio set in our hostel in Lahore.

The essence of the broadcast was that he would shortly convene a conference with leaders of all major political parties to resolve the political deadlock and initiate steps towards associating Indian leaders in governance of the country. "Delhi is too hot," he said, "we shall meet in Simla."

We, the listeners, wondered with whom he would hold the conference when all the top leaders were in jail. But as the broadcast proceeded further, came the next announcement "Orders have already been issued for immediate release of all the members of Congress Working Committee under detention (since 1942)." It is time, he said, for "us" on either side to "forgive and forget" what has happened and prepare ourselves for a new era of trust and goodwill. I was touched by his words.

The Simla conference was a high point of Wavell's Viceroyalty. The proposal was for a provisional cabinet, later called Interim Government, with equal Hindu and Muslim representation.

Among the principals at the Simla Conference were Congress President Maulana Azad, Muslim League's Jinnah, and Shiromani Akali Dal's Master Tara Singh, a prominent Sikh leader. Other invitees included the premiers of the provinces governed by elected governments - Punjab, Sindh, and Bengal - and former premiers of the eight remaining Provinces, who had resigned in 1939 upon the outbreak of the War. Princely India, home to one-fourth of the country's population, was unrepresented.

Simla was the summer capital of the Indian government, and also of the province of Punjab. I had relatives with whom I could stay in Simla, and went to observe the conference.

I reached two days before the conference was to start. Maulana Azad, just released from jail, arrived the next day. As his car entered Simla around 8 p.m., the crowd awaiting him was unmanageable. I was in the first row of spectators. When Azad's slow-moving car reached the point at which I was standing, it left side lightly grazed past me. In fact, my right cheek rubbed against its glass pane.

Gandhi was not an invitee to conference but was in Simla for a one-on-one meeting with Wavell before the Conference started. He stayed, as always, as a guest of Rajkumari Amrit Kaur in her bungalow in Summer Hill, a suburb of Simla.

The historic conference failed. Jinnah refused to allow any Muslim nominee from the Congress party. He harshly denigrated Congress President Azad as a "show boy."

Wavell's efforts to transfer power to Indian hands did not stop after the failure of the Simla conference. On September 2, 1946, he disbanded his cabinet, the Viceroy's Executive Council, comprising appointees of British Government. In its place, Wavell formed a new Executive Council, also called the Interim Government, with members nominated by the major political parties. This was the first time that popular leaders were associated with governance at the national level. Jawaharlal Nehru, as leader of the largest party, held the title Vice President of the Council (and de facto, although not formally, Prime Minister of the Interim Government). Predictably, Jinnah objected to this description of Nehru's job. Jinnah said that Nehru was nothing more than the Member for External Affairs in the Viceroy's Executive Council.

However, people rejoiced. Nehru delivered his first broadcast on All India Radio, which had hitherto been a propaganda tool for the British. Nehru began his address with the salutation, "Friends and Comrades."

The arrangement did not work smoothly. The Congress and Muslim League members of the Interim Government kept on quarrelling with each other in Cabinet meetings, with the Viceroy presiding. Besides, there was ongoing inter-departmental war between the departments (not called Ministries then) under the two parties.

Wavell made his best efforts to patch up the differences, but with no success. History, however, is often cruel. Wavell received a cable one morning from London. Holding it in his hand, he called for his Private Secretary, Sir George Abel. In a distressed voice, Wavell said, "They have sacked me, George."

Although Wavell felt that he had failed, I believe he was the single most important Englishman who facilitated the transfer of power from British to Indian hands. It is most unfortunate that neither England nor India has recognised his role fittingly. Both British and Indian historians have given much greater prominence to Lord Mountbatten, forgetting that his role was minor. Nehru, in particular, unjustly downplayed Wavell's contribution, possibly carried away by his infatuation with Wavell's successor Lord Mountbatten and his wife. Among Indian leaders, only Maulana Azad, in his book India Wins Freedom recognized the crucial role that Wavell played.

Punjab's Khizar Hayat Tiwana holds back Jinnah

Nawab Malik Sir Khizar Hayat Tiwana became Prime Minister, the equivalent of a Chief Minister today, of the state of Punjab in December 1942. Born in 1900, he had served as an army officer in World War I. He maintained an elegant bearing, as testified in 1946 by a visiting lady member of a British parliamentary delegation. She said of him, "The Nawab has a pleasing personality."

Khizar had strayed into politics in the 1930s through the accident of his birth. By virtue of his father's holding of large agricultural estates and his political connections, he became a member of the Unionist Party, which represented elite agrarian interests in Punjab. The party reflected Punjab's diverse population. The party's leaders and members came from the Muslim, Hindu, and Sikh communities. A prominent Hindu Jat and a towering Indian personality, Sir Chhotu Ram, was one of the party's founding members.

In 1937, Khizar had won a seat in the Punjab Assembly and joined the cabinet of Sir Sikandar Hayat, another founder of the Unionist Party. Reflecting Punjab's religious composition, the Sikandar government worked in coalition with the Congress party and Shiromani Akali Dal, the prominent Sikh party.

To maintain his coalition, Sikandar opposed the partition of Pakistan along religious lines. Such opposition was necessary to retain the confidence of the formidable Akali Dal leader, Master Tara Singh. But opposition to Pakistan created a conflict with Jinnah, for whom Punjab was to be Pakistan's jewel.

Sikandar managed these centrifugal forces by maintaining an uneasy truce with Jinnah. But in December 1942, Sikandar suddenly died of a heart attack. Khizar became Punjab's Prime Minister.

Khizar, more vehemently than Sikandar, opposed the partition of Punjab and, hence, unlike his predecessor, refused to deal with an increasingly impatient and frustrated Jinnah. Finding the situation intolerable and unable to dislodge Khizar, Jinnah's followers, with his approval, unleashed an agitation to end to Khizar's premiership. They denounced him as a "quisling" and a "kafir."

Khizar was fighting an uphill battle. Making matter worse, Sir Chhotu Ram died in January 1945. Soon, Muslim members of the Unionist party began to defect to Jinnah's Muslim League.

In the January 1946 provincial elections, the Muslim League won the largest number of seats in the Punjab Assembly. But these seats were not sufficient to command a majority and form a government. Khizar, with far fewer Unionist Party seats, stitched together a coalition with the Congress and Akali Dal and retained his position as the state's prime minister.

The Muslim League stepped up its campaign to oust Khizar. In Lahore, starting in February 1947, a mile-long procession would pass every day on the city's glamorous "Mall" with the agitators beating their chests and shouting "Taza khabar, mar gaya Khizar' (hot-off-the-press, Khizar is dead).

Lahore was not just Punjab's capital. It was an important and unique city. With a population of 600,000 people, it was larger than Delhi. About 55 percent of the population was Muslim, with the rest, about 250,000 people, comprising Hindus and Sikhs. The Hindus and Sikhs formed a core and vibrant element of the city's social, cultural, and intellectual elite. The three religious groups had learned over several decades to live with each other. Bonds of history, culture, and politics had kept them tied to each other.

Thus, the early processions trying to dislodge Khizar were non-violent. Indeed, the jolly participants would wave me along as I cut across the line of their procession. However, despite its good nature, continuous agitation became disruptive for Lahore's residents for whom the Mall was a major commercial area. The disruption was even more severe in other parts of Punjab.

Through all this, Khizar remained determined to prevent a Muslim League government in Punjab. On March 3, 1947, he reconfigured his government. My diary reminds me that that evening, I saw the brilliant Hollywood film Devotion in the Plaza theatre, located opposite the Provincial Assembly.

However, the lead entry in my diary for March 4 reads, "Riots begin - an overnight change in situation."

Khizar's precarious government had remarkably held together a fragile peace in Lahore even as rioting had spread through many Punjabi cities, and even to parts of Delhi. But Jinnah finally broke through Lahore's ethos and Khizar's resistance. Jinnah's campaign of coercion and intimidation, executed at a safe distance from his palatial home in Bombay, led to its inevitable consequence.

That March 4 morning, a hostel mate woke me with the words, "the mob has at last awoken." The history of what we now call "sub-continent" abruptly changed. News came early in the morning that Khizar had resigned. Later that day, the Sikh leader Master Tara Singh unsheathed his sword and shouted "Pakistan Murdabad (Death to Pakistan)" on the open platform of Punjab Legislative Assembly.

Up until that moment, Lahore had remained free from communal riots, unlike Calcutta, Bombay, Delhi and Peshawar, which had suffered from clashes and riots since August of 1946. Now, the madness engulfed Lahore.

Khizar faded from public consciousness after his forced resignation. In the early years after partition, he lived briefly in Simla, now in India, but returned to Pakistani Punjab. The government hounded him and expropriated some of his properties. According to a New York Times obituary, Khizar died in January 1975 while visiting San Francisco for medical treatment. A son, based in Chicago, survived him.

The virus of hate spreads its havoc

Once Khizar abruptly resigned on March 4, 1947, it was impossible to hold back the virus of hate. Ewing Hall authorities instructed us to stay within the hostel. The University postponed the exams, which were due to start shortly. Banks and offices shut their doors. Life came to a standstill. Inside the hostel, we played cards and listened anxiously to the news on the radio. I slipped out for about half an hour to the nearby General Post Office to send a telegram home saying that I was safe.

Jinnah's goal was to install a Muslim League government in Punjab. For the time being, however, following the Khizar government's resignation, Sir Evan Jenkins, the Governor of the Province, took over the administration.

The relations between Hindus and Muslims in the hostel continued to be cordial. On the evening of March 5, there was a rumour that a mob was attacking the hostel. Students ran up to the flat of the Warden, Professor Samuels Lal, and asked him to call the police. The professor was a devout Christian. Have faith in God, he said. Although this response annoyed the students, his reasoning was, in retrospect, sensible. The communally infected police would only have fomented trouble. The night passed quietly.

Matters improved the next day. My closest friend Navroz Khan (a Balochistani, and an ardent supporter of Pakistan), who slept normally until 10 a.m., slept longer (our common attendant Bhagat Singh, a Sikh, informed me at about 11 a.m. ‘Babuji, Navroz Khan sutta paya hai [Sir, Navroz Khan is still fast asleep]). I went to visit friends living nearby. We spent more time playing games of cards, gossiping, and listening to the radio. News kept pouring in about communal rioting in cities west of Lahore and in Amritsar on the east.

On March 8, the Congress Working Committee adopted a resolution asking for the partition of Punjab, thus finally giving tacit consent to partition of India.

Students started leaving the hostel and returning home, which in most cases was close by. In my case, Alwar was 400 miles away, and rail travel was dangerous. It occurred to me that our family friend Mr. P.C. Khanna lived in the city. He was the first Indian Chief Engineer of the Northern Railway. Mayo Garden, the well-protected Railway Colony, was a safe harbour. I called him from a phone in the hostel's office-library complex, and he warmly invited me to his spacious home with its large compound beyond the reach of rioters.

Seeking the same protection as I sought, another Lahore-based family had already moved into the Khanna's house. The sentiment in the house was deeply anti-Muslim. Some in the house murmured darkly that a common Muslim friend of ours, a U.P. Muslim, and a senior Central Government official posted in Lahore, whom I thought to be very liberal, was diehard communal, as good as a dagger-wielding Muslim, who would stab you from behind if given the opportunity.

Matters calmed down, and I returned to Ewing Hall on March 10. The next day, March 11, a group of Lahore's citizens celebrated "Anti-Pakistan Day," amidst high tension. But the day passed peacefully. On March 14, Nehru, effectively Prime Minister in the Interim Government at the centre, visited Lahore to take stock of the situation. That same day, my friend Madan Lal Khanna, about whose safety I had been worried because he lived in one of the most riot-affected areas of old Lahore city, visited me to my great relief. Classes resumed around March 20.

On March 29, after attending the last class, I left by train for Alwar. My parents, and my friends Prabhu Shankar and Har Prasad were keen to hear all details of events in Lahore. I spent over a month in Alwar, most of the time studying, although remaining uncertain about the date of final examination.

I returned to Lahore on May 3, believing that it would soon be time for examinations. The city was peaceful but there was no indication about the date of the examination. On May 14, the trouble started again. But the tension kept turning on and off. The hostel authorities did not want students hanging around - they did not want to be responsible in case matters turned ugly.

My uncle and aunt were on a brief visit from Balloki, a canal township about 50 miles from Lahore. At the Balloki head works, the Lower Bari Doab Canal emerged from the river Ravi. My uncle was the Executive Engineer in-charge of the head works. When he and my aunt returned on the morning of May 21, I drove back with them. There was a feeling of relief as soon as we were out of the city. We reached Balloki at 10.30 a.m.

I thought I was going away for a short while to bide my time until the university scheduled our final exam. I had loaned Rs. 40 to two friends and had myself borrowed a book from a friend. Later, I received an angry letter from the friend who had loaned me his book. We patched up, however, and became lifelong friends when we met only a short time later as colleagues at the Reserve Bank of India.

It turned out my Balloki stay was not a temporary absence from Lahore. Those weeks coincided with momentous decisions about our futures. Wavell's successor Lord Mountbatten had taken over as Viceroy in February 1947. He was 47 years old, handsome, and accompanied by a wife who played an important role during his term of office. Like Wavell, Mountbatten was from the Armed services, Navy in his case. He had also a member of royalty, as one of the numerous great-grandchildren of Queen Victoria. He had met Nehru earlier when commanding in a naval fleet in Singapore. The chord of friendship that developed between him and Nehru caused much anxiety among the Muslim Leaguers.

Campbell Johnson, then a young aide of Mountbatten, has written in his memoirs, Mission with Mountbatten, that the new Viceroy was playing with formulas for dividing India when the British left. He seemed to have converged on a plan to transfer power to the provinces that were already self-governing. Thus, each province would be a sovereign nation-state. Mountbatten had conveyed the proposal to London but had not discussed it with Indian leaders.

In late May 1947, while Mountbatten was in his Simla residence, Nehru was his guest. V.P. Menon, constitutional adviser to the Viceroy, was also present, although away from the main residence and occupying a guest room in the Viceregal Lodge complex.

One evening, at dinner, perhaps after an extra glass of whisky, Mountbatten, revealed to Nehru his plan to make India's Provinces independent states. Nehru, a distinguished historian, flew into a rage. Mountbatten, he said, was going to "balkanize" India.

When Nehru refused to proceed with the dinner, Menon was summoned from the Lodge and asked to draft an alternative. He worked overnight to produce his plan.

Next morning, Mountbatten left Simla, accompanied by Menon. They drove in the Viceroy's car, followed by cars carrying his staff, passing through towns in the region now called Haryana as curious onlookers watched the procession. Soon after, Mountbatten, accompanied by Lady Mountbatten and Menon, left for London.

On June 3, Mountbatten, now back in India, made a historic broadcast. I was still in Balloki and anxious to hear the broadcast. The town had no electricity, and there was no battery-operated radio set in my uncle's home. There was, however a battery-operated radio set in a house about two miles away. I walked to that house accompanied by my uncle's orderly, Mohammed Ali, to listen to the broadcast.

The British, Mountbatten said in his broadcast, would transfer power to two new sovereign nations, one would retain the name India, and the other would be called Pakistan. Jinnah's dream would soon be reality. Although not fully so. Pakistan would be much smaller than what he had demanded\; some even referred to it as "truncated Pakistan." British Paramountcy over the princely states would "lapse," but the rest of their future was left vague. (That vagueness was ultimately resolved by the great post-independence statesman Vallabhbhai Patel, ably aided in this task by V.P. Menon).

The orderly Mohammed Ali, who had accompanied me to listen to Lord Mountbatten's radio address, did not understand English. After I summarized the main messages, he exclaimed "Sahib, mulk ka batwara nahin hona chahiye (Sir, the country should not be divided)."

But this ship had sailed. The mulk (country) to which Mohammed Ali belonged was about to undergo not only a change in its name but also in its ethos and culture. I was never able to find out how he fared under the new dispensation in Pakistan.

The Balloki stay was pleasant. I often traveled with my uncle on his inspection tours during which we stayed in different Rest Houses. The water channels from the main canal provided pleasant swimming opportunities. My uncle, aunt, and I played a card game called "cut throat," a 3-person variation of bridge when a fourth player was not available. I grew particularly attached to my young cousin whose vocabulary was increasing faster than her ability to pronounce words. She was fascinated by "lel gaadis," (rail trains).

I stayed in Balloki for 27 days. On the morning of June 18, 1947, taking advantage of another lull in the violence, my hosts drove me back to Lahore. The atmosphere in the city was tense. We went to Ewing Hall for a few minutes for me to pick up some clothes and books from my room. We then rushed to the railway station. Parting with my uncle and aunt was emotional. At 8:45 p.m., I caught the Punjab Mail to Delhi. The train journey to Delhi was mercifully uneventful.

In the days after my departure, terror in Lahore flared up. Amidst the rioting, the city's fate remained undecided - would it be in India or in Pakistan? Lahore was only 35 miles away from Amritsar, the great Sikh city. Pakistani leaders claimed it based on a narrow Muslim majority\; Indian leaders claimed it highlighting Hindu and Sikh wealth and property. Sir Cyril Radcliffe, who drew the partition line, decided that Pakistan needed Lahore to compete with the major metropolises that India would inherit.

Lahore's population of 250,000 Hindus and Sikhs quickly dwindled down to a few hundred. Many converted to Islam. The lucky ones made the tortuous journey across the border to India. Many, however, were killed. Some prominent Hindus and Sikhs were assassinated. Among them was Professor Brij Narain, a well-known economics teacher and known for being a liberal, was brutally murdered.

In India, few had heard of Balloki. However, in the days after partition, the 9:00 p.m. news closely tracked the migration through Balloki. Thousands, who were on the move from Pakistan to India, crossed the bridge at Balloki head works. My little cousin - now the 74-year old Veena Sharma - has written in harrowing and heart-stopping detail of their unending encounters with death on their trek back to India.

The 90-year-old institution of British Viceroyalty (175 years of British rule, if we go back to Warren Hastings of the East India Company) was consigned to history. In the transition that followed, Mountbatten continued as Governor-General of India. But Indians would henceforth govern themselves. The person symbolising that change would be khaddar-clad Jawaharlal Nehru. The rising sun of India's freedom created a sense of excitement I had never felt before.

My transition, however, was not over. I faced a worrying uncertainty about my future. I had not completed my final exams. Were my two years of M.A. studies going to be a waste? As I sat at home mulling options, my father suggested that I forget the economics degree and enrol for a law degree in Alwar's Raj Rishi College. I did that, but my heart was not in it.

From extraordinary situations, novel remedies emerge. The news appeared that a new University with the name East Punjab University had been set up at Solan in Simla Hills (30 miles down Simla). The University issued a press notification asking the students displaced from Lahore to register with it. I did so. They announced the date and place of the examination, which I took at a shabby hall near Gol Market in Delhi. I received my degree. The certificate did not name a college, as was conventional. Hence, my happy association with Forman Christian College was erased. I was sorry also because F.C. College then was a bigger name than Delhi's St. Stephen's College at the time. I wrote to the F.C. College Principal and to Warden Professor Samuels Lal. Both sent handsome certificates.

I returned to Lahore 52 years after I had hastily left. On March 16, 1999, my wife I travelled from Delhi on the Indo-Pak Friendship Bus, introduced a day earlier.

Epilogue

In Alwar, Agra, and Lahore, I lived and studied with Muslims. I saw how even integrated communities fell prey to the politics of divisiveness. Once Jinnah sowed the early seeds of partition, the distance between Hindus and Muslims grew. Even Gandhiji was unable to prevent the divide from growing bigger. The journalist Leonard Mosley has written in gripping detail how Gandhiji camped in Calcutta during the transition to partition in a bid to prevent a recurrence of the previous year's bloody riots. He insisted that the flamboyant Suhrawardhy join him in evening prayer meetings and walks through the city with Hindu and Muslim followers. A sense of goodwill grew and not a drop of blood was shed in the East, even as millions massacred each other in the West. While Muslims, including Jinnah, often taunted Gandhi, ultimately a bullet fired by a Hindu nationalist killed him.

© R C Mody 2019

Comments

Sir I am journalist and wish

My email is indiaofthepast

Add new comment