Latest Contributions

The Day Prime Minister Nehru Died

Category:

Tags:

Editor's note: Several people have written their memories of the day Prime Minister Nehru died in May 1964. If you have memories of that day, please contribute your memories.

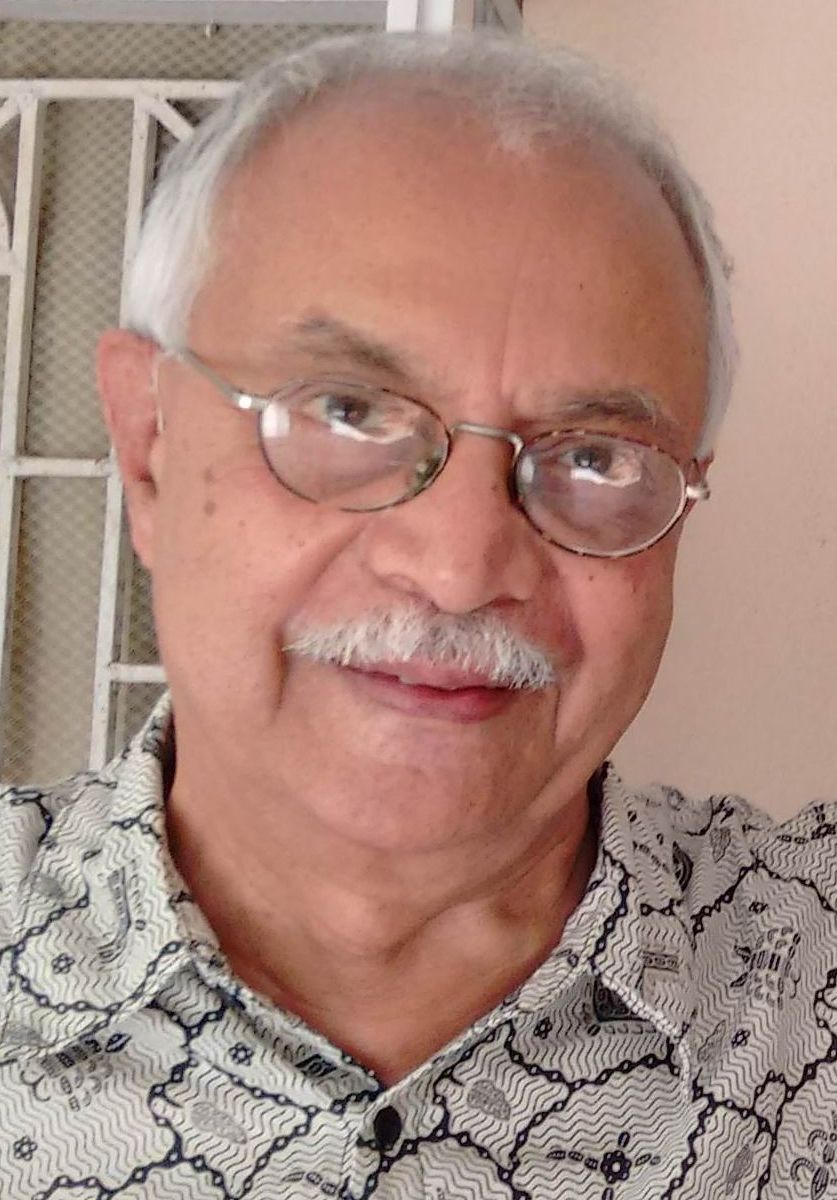

Authors

Remembering Nehru

Kamakshi Balasubramanian is a retired educator living in Mysore. She is an occasional writer. Her interests include cinema, popular culture, travel (particularly within India), and sewing by hand. Kamakshi received her higher education in India, the erstwhile U.S.S.R., and the U.S.A. She speaks Tamil, English, and Russian fluently, and knows Hindi.

The news reached us in the late afternoon. The radio was playing mournful music, and our summer holiday spirit ended abruptly. I had just finished high school.

Nehru's death was the first major national loss I experienced. We knew he was ailing. But you don't wish for a family member's death, at least not when you are very young and can't know that death is sometimes a deliverance. Not one of us siblings was ready to hear that he was gone.

We saw, in the newsreels at the cinema, Nehru's last journey. But before that, we heard over the radio the running commentary of that sad and long event. I recall something unusual about his cremation. There were people besides his immediate family close to the pyre. I don't remember who lit the pyre, though.

Nehru's ashes were scattered all over India, the land he loved. We were on a train to Chennai. At some station, we happened to see that special train carrying the great man's ashes. I shall never forget that moment, so powerful it was.

Nehru was the national father figure for me, although Mahatma Gandhi was called the Father of the Nation. For me, as a child, Gandhi had the grandfather image, and in Tamil, we did say காந்தித்தாத்தா(Grandpa Gandhi) and sing about him using that loving term.

On a small personal note, I celebrate my birthday on 14th November, Children's Day (also Nehru's birthday), and "chacha" Nehru used to be the recipient of our adoration. I thought I was special because of that. And on 27th May 1964, my bewilderment and sorrow were great partly because I felt that some celebration was gone from my life.

_____________________________________

© Kamakshi Balasubramanian. Published July 2019.

****************************************************************************

That Day: May 27, 1964

Vijay Padaki is a theatre educator. He has been a life member of Bangalore Little Theatre (BLT) since its inception in 1960. He has written over 50 plays, produced widely in India and abroad. In addition, he has adapted and translated several Indian plays into English. By professional training, Vijay is a psychologist and behavioural scientist, and has vast experience in management consultancy, policy research and training in the areas of Organization and Institutional Development.

Ahmedabad Textile Industry's Research Association (ATIRA) was a model cooperative R&\;D institution set up by and for the Indian textile system, particularly the composite mills in western India. There were over sixty textile mills within a radius of ten kilometers. ATIRA, created in 1948, was yet another product of Jawaharlal Nehru's vision of a modern industrial India. Gujarati enterprise was matched by Central government funds in ATIRA becoming the premier cooperative R&\;D establishment. Nehru himself inaugurated the state of the art research centre in April 1954.

I joined ATIRA as a Scientific Officer ten years later, in April 1964. This was the beginning of my career in applied research. All of us felt the presence of Nehru in the ATIRA premises all the time, not the least important reason being his image in the reception area. A less visible but significant presence was through the scientific temper and secular ideology that Nehru brought to institutions in that era.

On May 27, 1964, I left for an assignment in a mill in the morning. I was to return to the campus by lunch. There was a delay in my return. As a bachelor, I relied on the cafeteria for lunch, so I had thoughts of stopping for a bite on the way back. On the drive back I noticed that the roads appeared deserted. There was hardly any traffic. Shops were downing their shutters. The driver of the staff car pulled up to a lone policeman and asked what had happened. He broke the news that Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had passed away in Delhi. There was a sense of disbelief among people. It was unacceptable. Since most early reports had mentioned a stroke or a heart attack, people hoped hard that there would be a news bulletin to say he had survived. He had survived four assassination attempts, had he not?

At 2 PM the official announcement of his demise was made. The news traveled by telegrams and All India Radio.

By four in the afternoon a dark and heavy pall had descended on the entire city of Ahmedabad. ATIRA had lost a parent.

_______________________________________

© Vijay Padaki. Published July 2019

****************************************************************************

Pandit Nehru Personal Memeories

Born in 1941, Vinod Puri was brought up and educated in Amritsar. He attended Government Medical College, and subsequently trained as a surgeon at PGI, Chandigarh. He left for USA in 1969, and retired in 2003 as Director of Critical Care Services at a teaching hospital in Michigan. Married with two grown sons, he continues to visit India at least once a year.

The day of Pandit Nehru's death at the end of May in 1964 was rather ‘nothing much happening' kind of time for me. I had finished the final year of my MBBS course with final examinations in March/April. The results were out, and I had celebrated with a vacation in the hill station Shimla with friends. All that remained was a six-month internship before we got our degree to start a house job.

Panditji belonged to our parents' generation. The way he had dominated the Indian political scene after 1947 appears amazing in retrospect. The press was always posing the question, ‘After Nehru who?' People worried about it. By the time of his death, Nehru had lost some lustre. The Sino-Indian war of 1962 was such an event that Nehru had taken it as a personal betrayal.

Pandit Nehru of the newsreels and pictures in the Illustrated Weekly was rarely seen. His political rallies of the 1952 and 1957 which I had heard of in Amritsar as a child and read about in the vernacular newspapers was no longer uppermost in my mind. There was sadness at Nehru's death and a general sense of loss. Nehru had so ably steered Indian society in the right direction after independence. As doctors, my friends and I were also curious about the cause of his death: heart attack or a dissecting aneurysm?

The personal memory of the dashing and handsome prime minister I cherish is from the early 1950s Our Amritsar home was in Goal Bagh, a rare patch of green playgrounds and gardens just outside the walled city. Every few years an exhibit would be held on the grounds. All kinds of products will be shown at different stalls, and there would even be some entertainment. For a developing country, it was exciting to see consumer goods which were coming to the market. Panditji was in town for the annual meeting of the Indian National Congress Party. It was rumored that on that evening he will be visiting the exhibit outside our house.

In anticipation, many of our family members and neighbors expectantly gathered on the second story verandah of our house. The area outside our house was blocked with corrugated iron sheets. The lights in the stalls were coming on. Suddenly someone shouted, "There he is!" In a group of five or six officials, Pandit Nehru was visible in his white cap and achkan! One official from the group drew Panditji's attention to our house pointing at it. We all saw it. Pandit Nehru was reputed to be imperious and restless. For a fraction of minute, he looked up, saw about a dozen folks leaning against a railing and then briskly walked off! He hadn't waved but patiently listened to the official.

The speculation amongst the grownups was that the official was pointing to the house because of its connection with Gandhi, and Pandit Nehru had acknowledged that! In the 1920s during a visit to Amritsar, Gandhiji had used the second story of our still unfinished house to address a gathering of people in Goal Bagh. For years afterward, our house had been known as Gandhiji wali kothi (Home associated with Gandhiji).

Who knows?

But I was fortunate to see several pictures of Panditji in the cottage in Dalhousie where he had spent time during his vacations in the 1950s. This cottage once belonged to Raizada Hans Raj Sondhi, an esteemed freedom fighter and member of the Indian Parliament. As it happens, he was my wife Kasturi'sa maternal grandfather. That is how I stayed in that cottage in 2004.

_______________________________________

© Vinod Puri. Published July 2019

****************************************************************************

Nehru - As I Remember Him

Meenakshi Hooja (nee Mathur) was born at Jhalawar on 26th June, 1952 and after spending early years of her childhood at Jhalawar, Bikaner and Ajmer moved to Jaipur with her parents and family. Meenakshi taught Political Science at the University of Rajasthan before joining the Rajasthan Cadre of Indian Administrative Service in 1975. She served on many important positions in Government of Rajasthan and Government of India. She is widely travelled in India and abroad and was a visiting fellow at Queen Elizabeth House, Oxford in 1999-2000. Post retirement, she was a Member of the Central Administrative Tribunal. She has written on a number of development and administration related subjects, and published books of poetry in Hindi and English.

This day 27th May, more than 50 years ago, in 1964, we heard the news on our radio. Jawaharlal Nehru, our Prime Minister, was no more. We immediately closed the music and film songs, and switched to All-India Radio to hear and rehear, what came to us in the family, as a big shock. I remember feeling very sad and had tears in my eyes, as perhaps did the entire nation. We did not want to or like to believe it! That day, there was hail and storm, and the sky was laden with the blowing sand. It was as if heaven itself had blazed forth the death of a great man.

At that time, I remembered the speech he gave when India became Independent on 15th August 1947, and later when Mahatma Gandhi died. We felt that light had gone out now also, as Nehruji himself was no more.

I was about 12 years old then, seventh out of the eight siblings, all living with our parents, father Shri Khemchand and mother Smt Dayavanti, Dadi and Chacha in Jwala Bhawan, C-Scheme, Jaipur. I was old enough to understand the tragedy and its sorrow but yet to fully fathom the complex multi-faceted dimensions of our polity, economy, and society. However I did realise, as I lived in the family and neighbourhood and studied in the prestigious MGD Girls School (at that time and right up to 1976, the only Girls' Public School in India) that India was a country in which I was proud to be born and live in, and that if we did our duties at home and school, and also as citizens, it could become better.

Amongst many individuals and leaders, who had contributed to the greatness of our country was Jawaharlal Nehru, or Panditji as my father and many others addressed him. Somehow I always called him Nehruji.

We had high regard and respect for Nehru, even as young individuals. To many of us, he was a bright person who could get admission to top ranking educational institutions like Harrow and Cambridge and pass out successfully. Such an achievement was a source of inspiration. To this date also, such a feat, be it in any place or country, is much admired, and I feel, will continue to be. Nehru had an impressive and charming personality, was tall, good looking and handsome, keeping himself fit through yoga, even Sheershaasan. He was a lawyer, a scholar, an intellectual and more than that he wrote books even while in prison. How he managed to remember so much information and data and then record it, completely overwhelmed us and made us idolise him, even as school students. A doyen of the freedom movement, lending us faith in our capabilities, we stood fascinated by Nehru and his aura.

As we grew up, we learnt more about Nehru's contribution. Firmly laying the foundation of democracy, playing a key role in preparing the Constitution, forming and leading the Non Aligned movement in a world divided in blocks, building the scientific temper as an essence of education, setting up projects for irrigation, focusing on agriculture and heavy industries, writing to the Chief Ministers, taking up development through inter-sectoral planning and giving India a place under the sun\; these and more accomplishments made us realise his contributions to our nation and the world .

Closer to home, and in the family, we knew of him as the Prime Minister who visited Udaipur in the early 1950s when my father was Collector there. He used to tell us that Panditji protested and appeared annoyed when he saw large crowds at the Udiapur airport. But when my father told him (after some quick thinking) that they have come for his darshan (lore has the exact words being "sir, you are a victim of your own popularity"), he laughed and was satisfied with the arrangements.

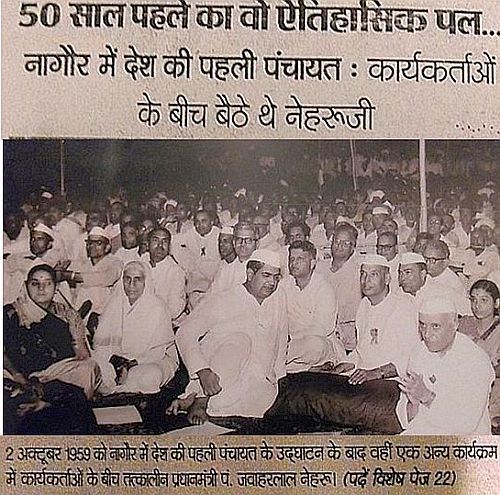

Later in the 1960s, my eldest brother Prof PC Mathur (now sadly no more) received the prize for the Best Essay from Nehruji himself in a competition organised by the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA). Later, after my marriage to Rakesh (a colleague in the IAS from the 1974 batch) I learnt that the Police Memorial in Jaipur, a homage to the martyrs, and popularly known as the famous landmark Teen Moorti, made by my sculptor mother-in-law Smt Usha Rani Hooja, was unveiled by none other than Nehruji on 5th November 1963. This was also, unfortunately, Nehru's last visit to Jaipur and Rajasthan. And wonder of wonders, in an exhibition on Panchayati Raj organized by the Government of Rajasthan in Jawahar Kala Kendra in 2009, our sons Rajat and Rakshat came across a photograph of Nehruji in Nagore on 2nd October where he inaugurated the Panchayati Raj and that featured Rakesh's paternal grandmother popularly known as Mata Hooja! She had contributed immensely to girl's education, primarily through Jullandhar Kanya Vidyalaya, where she studied and taught. Knowing Nehruji in this way, through family members' connections also made me feel quite good.

Front row, L to R: Mrs. Sukhadia, wife of Rajasthan's Chief Minister, Mata Hooja, Mohan Lal Sukhadia, Rajasthan's Chief Minister, Prime Minister Nehru. Nagaur, Rajasthan, 1959.

This photo is from a Hindi newspaper. The heading translates as:

The Historic Moment Fifty Years Ago: Nehruji sitting with workers after the very first Panchayat in the country in Nagaur.

The footer of the photo translates as:

On 2nd October 1959, after the inauguration of the first Panchayat in the country, then Prime Minister Nehru sitting with workers and functionaries.

As I moved into Government service and schoolmates, family and friends also moved into their different professions and occupations, we became aware of some of Nehruji's shortcomings as a person as well as his policies like dealing with Kashmir issue, war with China, perhaps suppressing people's enterprise by giving State and Public sector an over dominant role. However, this only made him appear more human, and his other sterling contributions held forth and remained strong and enduring. He continued and continues to be for us a visionary, a writer and an intellectual, a capable and affectionate leader, dedicated to the country.

It is quite easy to find faults and belittle achievements. It happens nearly everywhere\; in homes, between friends, neighbourhoods, groups, associations, across time and space. The tricky part is to make balanced assessments and arrive at a fair verdict. In the case of Nehruji, also we need to study and restudy his work and life. Mere criticism for the sake of it takes us nowhere. Even if we wish to judge him by current standards and the long-term impact of his policies and decisions, we must do it as objectively as possible. That will be the scientific temper and humanism he sought to inculcate in us. Today is a good time and day to reflect on this.

________________________________________________________________

© Meenakshi Hooja. Published July 2019

****************************************************************************

My Glimpses of India's First Prime Minister

Mira Kathuria Purohit had her early education in Presentation Convent, Delhi, MGD, Jaipur and Hindu College, Delhi. She is a Pediatrician, having pursued her medical studies in SMS Medical College, Jaipur. She served in Rajasthan Government devoting her working career to treating children and teaching budding doctors to treat kids. She retired as a Professor, and now leads a retired life in Jaipur.

In late May 1964, I was studying in Medical College in Jaipur but was home in Delhi for my short summer break. My bhua (father's younger sister Laj) was visiting us from Karachi, Pakistan, where her husband's family had stayed on after the Partition of India. My cousin Vijay, who was an engineering student in Baroda, was also home for the vacations.

We had finished lunch, and were relaxing, with the radio on (this was the pre-television era). Vividh Bharati, a popular Hindi channel of All India Radio, was playing film songs. Just after 2 pm, the music stopped. Within a minute or so, the tune changed to classical instrumental music. We were all wondering what had happened when the announcement was made. The Prime Minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, was no more!

All of us were stunned. Panditji, as he was popularly known, had been ill off and on for some time. So much so, that people had been debating who would take his place if something happened to him. The Illustrated Weekly, a popular magazine, had even brought out a whole issue to discuss ‘After Nehru Who?' Pandit Nehru had been the Prime Minister of India ever since the country's Independence in 1947 - a total of 17 years. It was difficult to imagine India without him at the helm.

All of us remained glued to the radio, waiting for more news. No one spoke. There was nothing to say. The mournful music continued. Later it was announced that the mortal remains would be kept at his residence, Teen Murti House, for public to pay their homage to the departed leader. All of us wanted to go - my Aunt Laj most of all.

By this time it was evening. No one wanted dinner, so off we went in our Fiat car. Already there was a queue - almost half a mile long and ever increasing. There was police bandobast (security), but there was hardly any need. It was a sad, orderly crowd. People, young and old, all stood, or sat on the ground, patiently waiting for darshan (viewing) of Panditji. People had come from across Delhi, and some were arriving in buses from other towns. Conversations were in whispers - as were ours. We started reminiscing and describing the glimpses that we had had of Chacha (uncle) Nehru. My Aunt had not lived in India after her wedding, and she felt she must hear all our experiences.

My first memory of him was when we had gone to the Red Fort grounds one Independence Day to see him unfurl India's flag from its ramparts. Perhaps it was 1949, and my cousin Vijay and I would have been about six years old, my younger sister, who was born in Independent India, a mere toddler. We lived in Old Delhi's Daryagunj, which was quite close to the Red Fort. We had walked down to the crowded venue. We children had to hang on to the elders for fear of getting lost or trampled.

I did remember the man in white standing on the ramparts of the fort, the flag going up, the cheering of the crowds, and the chants of Pundit Nehru zindabad! India was still young.

Of course, the speech was lost on me. Then came his Jai Hind, which signaled the end of his speech. Then came the National Anthem, for which we were told to stand absolutely still. On the way back home, my mother was quiet and sober. She seemed to be in an introspective mood. A few months later, on January 26, we went to India Gate to attend the Republic Day Parade - perhaps the first parade. It was after this that my mother remarked that this is what we must celebrate - not 15th August. There was too much khoon kharaba (bloodshed) at that time!

It was much later, growing up, that I could comprehend and understand the meaning of her words and her sadness and anguish brought about by memories of the Partition of India, linked to the country's Independence. That was perhaps the only time I attended the annual Independence Day ceremony with my family.

Another town, another speech, another memory. My father, an officer in the Post and Telegraph Department, was posted in Jaipur in the early 1950s - he had set up the first manual telephone exchange here. At that time housing was a problem, and many officers were living in officially allotted quarters in King Edward Memorial on Mirza Ismail Road (now this building houses the Police Headquarters). We also lived there.

During this period (perhaps 1951) Pandit Nehru had visited Jaipur and addressed a huge gathering from the Albert Hall (museum), in Ram Nivas Gardens, just across the road from where we lived. I had gone to hear the Prime Minister's speech with my parents. This time we were seated in front on chairs, and could see him quite clearly. He had a mesmerizing personality. Behind him stood a young lady, in a white sari. My mother pointed her out to me. "That is Panditji's daughter, Indira. See how smart she is. Really a wonderful daughter of a great man!"

Later, growing up in Delhi, as part of school groups, we would sit in front of the ramparts of the Red Fort and wave flags. Similarly, we would be at the Republic Day celebrations and glimpse Chacha Nehru. There would be functions at the National Stadium on Children's day, his birthday (14th November), and we would be participants. I remember an art competition organized by Shankar's Weekly, a popular magazine those days. An exhibition of all the entries was held, and all the participants, along with their parents or guardians, were invited on the final day function. Chacha Nehru was there, shaking hands with us! We were on cloud nine!

When I was in Medical College in Jaipur, he had visited this city in 1963 to unveil the Police Memorial, sculpted by my Aunt, Usha Rani Hooja. He also visited our college, and it was a grand occasion for us students. This was perhaps the last occasion that I saw him.

Now we were outside Teen Murti House, reminiscing while waiting for the queue to start moving. There was a slight drizzle off and on---as if the heavens were weeping! Very few people were carrying umbrellas on a hot summer night, but no one minded getting wet. Official cars were coming and going, as politicians, bureaucrats, and other VIPs came to pay their homage. The public waited.

It was sometime after 10 pm that the line started moving ever so slowly. Must have been after midnight that, at last, we entered the chamber where Panditji lay in state. There was pin-drop silence. The smell of incense pervaded the atmosphere. People in white surrounded the wake. Indira, his daughter, also in white, sat at the head end, surrounded by a few other ladies. Panditji was covered in white. He seemed to be sleeping - ever so peacefully, without a care in the world. After all, his worries were over! It was time for others to take over!

We entered from the foot end with folded hands and went around. Some people were crying, but silently. I noticed my mother's eyes were wet - a rare phenomenon for the strong, non-demonstrative woman that she was. My Aunt Laj was a very sensitive person. Her tears rolled down her cheeks freely. Once outside, she started sobbing. "I'm so sad he is gone, but glad I was here and could have a darshan of him! All of you live in Delhi, and have seen him often. You have so many memories. Living so far away, that too in Pakistan, I have nothing---at least I will have this memory now."

The funeral was the next day. A running commentary of the procession and the cremation was aired on All India Radio. We sat at home and listened to this - we had had our last glimpse of Chacha Nehru!

_______________________________________________________________

© Mira Purohit. Published July 2019

****************************************************************************

Memories of Pandit Nehru

Raja Ramanathan was born in Independent India, in Calcutta. He has spent the last sixty years or so growing up in different parts of the world, Singapore, England, India, the Middle East, and, in the last twenty five years, Canada.

On the day that Pandit Nehru died, I was in Bombay for my summer holidays. I was attending typewriting classes in the Fort area. After my class, I took a bus home to Sion. Around the time we neared Parel, a group of people stopped the bus saying ‘Nehruji had passed away'. The bus driver stopped the bus, and we all got down. The bus driver took the bus to the depot, and I walked home. On the way, I could see all the traffic was off the road. It was truly the end of an era. We heard many stories that he had actually died early morning, and the announcement came only mid-morning.

The next day my niece Radha was born. It was Buddha Jayanthi and the day was taken up between celebrating her birth and listening to the radio commentary of Panditji's funeral. My father, who, as a journalist, had worked closely with him held him in deep regard. In fact, at home, we had to always refer to him as Panditji, not even Nehruji, something I do even today.

A few months before his death, Panditji came to Bombay to attend the AICC session. An uncle took us in his car to the roads behind Santa Cruz airport, and we got a glimpse of Panditji as he drove past in a closed car almost slumped in the back seat. He was in no physical frame to stand in an open car wave to the crowds as the Prince had done in the past. In fact, that day, there were no crowds.

The day he died stands out in my memory because till then one never thought of another leader of that stature to lead India. Though since 1962 his credibility had whittled down, he was still the uncrowned King. In spite of all that is leveled against him these days, I think we are still a democracy because of his efforts. I see him as the maker of modern India. And what a handsome looking man!

______________________________________

© Raja Ramanathan. Published July 2019.

****************************************************************************

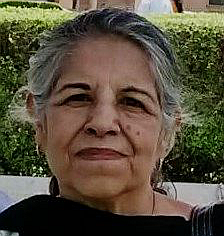

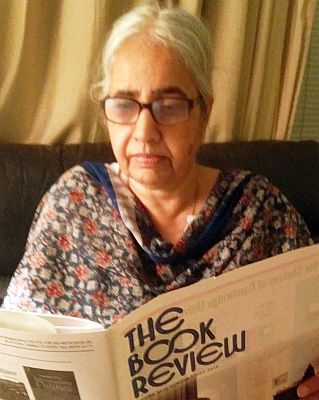

Nehru - As I Remember

Chandra Chari has a Masters in Ancient Indian History from Delhi University. She is currently the co-editor of The Book Review (est. 1976) and Chairperson of The Book Review Literary Trust. For more details regarding publications, please visit www.thebookreviewindia.org.

27 May 1964. I was in Bhopal with my parents and siblings, visiting my uncle. It was a beautiful day with a cool breeze blowing in. This was a time when Bhopal was still a hill station when coolers and air-conditioners were not thought of, much less needed, even at the height of summer, while most of India sweltered. The news of Panditji's death came in the afternoon on the radio in pre-television India. Fifty-five years later, the feeling of unbearable loss is still as fresh as it was on that summer afternoon. India was bereft. This may seem strange at a time when every pin-bowling individual who claims to comment on the past feels free to take pot-shots at a man who was the true maker of modern India.

As we sat listening, with tears barely concealed, to the commentary on the radio of what was happening in Teen Murti House, memories jostled with one another of what Panditji meant to a generation which had grown to adulthood under the leadership of his larger than life persona. The 1950s were years of idealism, and Nehru with his speeches calling out to the masses played no small role in imbuing the country with that idealism. I remember mass contact tours by ministers with bureaucrats, roads, schools and health care centres coming up with not merely government aid but people's willing contributions. Nehru's clarion call was answered by the people of India with overwhelming love, of which Nehru never failed to speak.

On a personal note, way back, as a child of 5, I remember announcing that Jawaharlal Nehru was a Tamilian because I wanted to belong! Then there was the time when with amusement we watched our youngest sibling going about waving a flag and chanting "Nehruji ka jhanda sab se ooncha (Nehru's flag flies highest)! It was as though India wanted to claim Nehru for our own. It was in 1957 that I had the chance to see Panditji for the first time when he came to Raipur. His public meeting took place right behind the Commissioner's bungalow, which my father happened to have been allotted. Panditji came late and the crowds waited patiently, feeling fully rewarded when at the end of the speech, he hurled his bouquet, as was his custom, to a small girl in front. How I wished it had been me!

On to Delhi from 1958, and the memory of my father's car being stopped on his way back from South Block, on the sunken road, while Panditji drove by in a white ambassador, hand on chin, and the red rose so prominent on his jacket. Not a year passed without my father driving us to the Red Fort to hear Panditji speak from the ramparts on August 15. Delhi was host to Presidents and Prime Ministers from the world over, and we took pride in the image of India that Nehru strove to build on the world stage.

And then, the debacle in 1962, when we grieved with Panditji at a dream of coexistence shattered. In Lady Shri Ram College, New Delhi by then, my most vivid memory is how the people of India stood up as one, to donate to the war effort, with women giving their gold jewellery, and knitting for the Army jawans, and shedding tears with Nehru as Lata Mangeshkar's golden voice sang Ai mere watan ke logon. The recriminations against his having been blind to warning signals came later, but in the moment of crisis, Nehru had the unstinting support of the nation.

After Nehru's funeral, his ashes were taken to various locations to scatter over water and land. My spouse-to-be within a year and I often talked about the day Nehru died. As a young Subdivisional Magistrate in Katni, he was detailed to be on duty as soon as the news came. Jabalpur (Arabic jabal for rock + Sanskrit pur for city), an extremely important administrative unit of CP&\; Berar under British rule, was the site of communal conflict throughout the 1860s. Growing up in this historic city, he recalled also being told that Gandhiji stayed at the Beohar Palace in 1933, that the Indian National Congress session in 1939 was held at Tripuri chaired by Subas Chandra Bose. In 1948, the eleven-year-old boy was witness to the teeming crowd, which gathered as Gandhiji's ashes were brought by Chief Minister Ravishankar Shukla to be immersed in the Narmada river at the Tilwara Ghat. The memories came tumbling as Gandhi's beloved pupil and heir died in 1964, and Jabalpur grieved again with India at the passing of an era.

I must conclude with my having had the opportunity to join the research staff of the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund (JNMF), which was set up soon after he died, with offices in the sylvan surroundings of Teen Murti House. I compiled and edited Nehru's public meeting speeches as well as the Congress Parliamentary Part debates, transcribed from recordings and translated all of his Hindi speeches from Hindi into English, which have been published in the Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru published by the JNMF. It was nothing short of reliving history through his words. The Selected Works project is nearing completion this year with the volumes now covering 1964, and once more, I feel afresh the pangs of sorrow which engulfed one on the day Nehru died.

_____________________

© Chandra Chari. Published July 2019.

****************************************************************************

My Memories of Panditji

After getting his M. Tech from IIT Bombay in 1961, Anand Barve joined Esso Oil Co in India. Worked in various capacities in Bombay and Singapore for 16 years. Worked as Technical Advisor to Ashok Birla, and built one plant in the Philippines for his joint venture. Then, he joined Bombay Dyeing and was VP, completing a project for the group. Left after 6 years to Join International Finance Corp (IFC) in Chemicals. Retired as Chief Engineer after 17 years in 2002. Continued as a consultant to IFC, Equity Funds and three companies till 2017

I was 10 or 11 years old. The year was probably 1950. We were staying in a big bungalow next to the Collector's home in Jalgaon, in what is now Maharashtra. The only decent open car was with the Collector. When Nehru decided to visit, there was no proper place for him to stay. Hence only for one night, the Collector decided to host him.

The next morning, Panditji was to address a rally in town, some four miles away, separated by two miles of no habitation. There was a minimal police escort. On that morning, my sister and I stood at our home's gate, waiting for the motorcade of three cars, including the police, to start from the Collector's home. We had flags in our hands, and flowers to offer if we got a chance.

After a wait of almost 45 minutes, the cars came out. When we saw Panditji, we waved the flags. He returned our gesture with a smile, but the cars did not stop. We were disappointed but had no choice.

I remember that, at his death, one of the best obituaries was written by a well-known Marathi author, P.K. Atre, who hated the Congress party but admired Panditji. He wrote that Panditji's complexion was like rose petals mashed in saffron.

After I grew up, we admired his vision to get steel mills, dams, canals, and a few other projects started. It was essential for agrarian India. We also admired the Five Year Plan, as explained by our teacher in school.

I was on training in the U.S. in 1963/64. On a cold dark night, on a rail station near Elizabeth in the New York area, a black person approached me. I was scared to death. But soon he asked me if I was from India, and if I knew how Panditji is doing. I had no idea that he had suffered a stroke as I had not read any newspaper for several months. I was surprised to see that an unknown person in the faraway USA knew of Panditji and his contributions to India's freedom.

He came to Bombay to address Congress meeting at Shanmukhananda Hall. But then he was slumping in the car, coming out of a stroke that he had suffered.

On his death, when I was working in Bombay, the whole city was like a desert. It was sad indeed for the entire Bombay and country.

_______________________________________

© Anand Barve. Published July 2019.

****************************************************************************

Remembering Jawaharlal Nehru

R. C. Mody has an M.A. in Economics and is a Certificated Associate of the Indian Institute of Bankers. He studied at Raj Rishi College (Alwar), Agra College (Agra), and Forman Christian College (Lahore). For over 35 years, he worked for the Reserve Bank of India, retiring as the head of an all-India department. He was also Principal of the RBI's Staff College. Now (in 2019), in his 93rd year, he is engaged in social work, reading, and writing. He lives in New Delhi with his wife. His email address is rameshcmody@gmail.com.

In 1912, the 23-year-old Jawaharlal Nehru returned to India after seven years as a student in England, where he was first a schoolboy at Harrow, then an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge, and lastly at the Inner Temple in London for his bar-at-law. His father, Motilal, a towering leader of the Allahabad bar with a flourishing practice, expected that the young and western-educated Jawaharlal would start as his apprentice and eventually emerge as a barrister of national fame.

But Jawaharlal's life took an altogether different turn. He found law uninteresting and the atmosphere of law chambers boring. There is no record of the number of briefs he took up or of how much he earned as a lawyer. All that we know is that he didn't stay long in the profession.

During the early days after his return from England, he spent time mostly in the company of English families in Allahabad. But very soon, he started drawing inspiration from the lives of great Indians like Tilak and Gokhale. After the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in April 1919, he turned into an uncompromising opponent of British rule over India.

Motilal was a member of Indian National Congress without being actively involved in its activities. Jawaharlal plunged headlong into the struggle for India's freedom, dragging his father along with him. Unlike Mohammad Ali Jinnah, a leading figure of Bombay bar who too was in the Congress then but without ‘spoiling the crease of his pants', Jawaharlal cast away his and family's western clothes. In fact, the Nehru family made a Holi of those clothes by burning them publicly, retaining just one suit. This was the one which Motilal had got specially stitched by a Saville Row tailor in London, and which he wore to attend the 1911 Delhi Durbar, to which he was invited as an eminent citizen of United Provinces.

Soon after, Gandhiji came on the scene, and Jawaharlal became his devoted disciple. The year 1921 was a watershed year in Jawaharlal's life as he performed his first pilgrimage to an Indian jail.

Even in pre-independence India, Jawaharlal became obsessed with China. He cultivated a relationship with the Kuomintang regime under Marshall Chiang Kai-shek. Then after independence, Nehru quickly warmed up to the Communist regime under Mao Zedong and Zhou En-lai. Nehru's China obsession helps us understand his last days.

The China shock

In December 1950, a few days before his death, Sardar Vallabhai Patel, Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister, warned Nehru against the Mao-Zhou regime in China. Nehru ignored the warning. India became the first non-communist country to extend recognition to the Communist government of China, even as many Western leaders described the Chinese leaders as the bandits of China.

Nehru became a friend of Zhou's, basing the friendship on the principle of peaceful co-existence between countries with different ideologies, epitomized by the word Panchsheel and by the slogan Hindi-Cheeni Bhai Bhai (Indians and Chinese are brothers). Nehru lobbied for the communist government to inherit the permanent membership of the U.N. Security Council in place of the Kuomintang regime.

But alas, the cordial relations between Nehru's India and communist China didn't last long. Early in 1959, India extended a warm welcome to Dalai Lama, Tibet's spiritual leader and virtual ruler of Tibet, who had fled from his home and seat of power in Lhasa under pressure from the Chinese government. Nehru assured him of his safety and security.

Around this time, the Chinese started intruding into Indian territory, across the McMahon Line in the Himalayas, the agreed border between the two countries. Chinese troops occupied territories that the Indians considered to be theirs. The Indian government considered the incursions as acts of aggression.

In this charged atmosphere, Zhou announced he was coming to India. He landed in Delhi on April 18, 1960. I received a pass for the reception of the Chinese leader at Palam airport, and took my 4-year-old son, Ashoka. As was typical in those days, security did not shield leaders from the public and we mixed freely with all, including some VIPs who had gathered there. As Nehru was waiting for the guest to land, he (known for his love of children) held Ashoka, and affectionately dragged him along several meters before letting him go.

In his meetings with Nehru and other senior Indian leaders during the visit, Zhou insisted that China had not occupied any Indian territory. He visited Morarji Desai and Govind Ballabh Pant, among others, to explain China's viewpoint. (He skipped V. K. Krishna Menon, India's Defence Minister) who was considered a controversial personality even by Indians.)

But all Indian leaders rejected Zhou's views. He returned empty handed.

In 1962, the Chinese army began more serious incursions into Indian territories. When Nehru heard the reports of these, he angrily ordered the Indian army to "throw them back." Such bravado proved counterproductive. In October 1962, the Chinese launched a blistering attack across the Himalayas, inflicting a humiliating defeat on India.

Nehru had misjudged on so many counts. His idealism had failed to recognize the crucial importance of power in international relations. His judgment failed to acknowledge the power imbalance between China and India.

The last days

In May 1964, Nehru renewed the effort to solve the 16-year-old Kashmir problem, which he had let fester all this time. Having imprisoned the Kashmiri leader Sheikh Abdullah since 1953, Nehru now ordered his release. From his house arrest in Kodaikanal, Abdullah came as Nehru's guest to the prime minister's home at Teen Murti House. Ironically, the two of them were old friends, and they met in a warn reunion.

Abdullah's press conference gave the world a sense of Nehru's fading health. He found Nehru sincere and affectionate as ever, Abdullah said, but physically he was a pale shadow of his past.

In another incident in May 1964, a Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) attended a meeting of the Planning Commission, which was chaired by Nehru at Teen Murti House. Nehru was not well enough to go to Yojana Bhawan, where the Planning Commission was located. Describing the proceedings in melancholy words, the RBI official said, "It took Nehru nearly 10 minutes to say a few words, with frequent stops to catch his breath." The meeting was short. "We were anxious to save him further effort and went out sadly, leaving him still sitting at the big table."

Nehru brought back Lal Bahadur Shastri as minister without portfolio. From then on, Shastri, who had earlier resigned as Home Minister under the Kamaraj Plan, assisted Nehru in his work. This development was Nehru's first public admission that he was not well. He tacitly also indicated that he wanted Lal Bahadur to succeed him.

Soon thereafter, Nehru addressed a press conference at Teen Murti House. A journalist asked him why he did he not formally anoint a successor in his lifetime. Nehru replied, "My lifetime is not going to end soon."

A day or so later Nehru went for rest and recuperation to Dehradun, his favourite resort in the foothills of Mussoorie. He had a very warm meeting there with his old friend Sri Prakasa, a person of his age and a renowned Congress leader who had held several diplomatic and political positions but had retired by then. Sri Prakasa, seeing Nehru's state of health, ventured to suggest that he should consider retirement, having served the country so well and for so long. Nehru just smiled. In his mind the lines of poet Robert Frost-which he had kept for some time on a side table close to his bed-were ringing, "The woods are lovely dark and deep but I have promises to keep and long to go before I sleep."

The Dehradun stay did refresh Nehru. He rejected suggestions that he should stay there longer to gain more strength. Work awaited him in Delhi. He had a simple vegetarian thali meal on the evening of May 26, after which he took a flight to Delhi. Back in Prime Minister's House, he retired for the night in his bedroom.

"So to sleep"

On May 27, I was in a chemist's shop in Connaught Place in Delhi. A stranger told me that Nehru was lying in a coma since the morning\; another stranger overhearing the news commented, "How can that be? He returned from Dehradun only last night, totally refreshed." Without trying to judge which one of the two was correct, I took my car and dashed home, about six miles away. Just I was entering the house, I heard a young lady from the adjacent house saying "Panditji guzar gai (Panditji has passed away)." I instantly broke down.

I switched on the radio (there was no TV then). Melancholy music was playing. In his usual erudite language, President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan paid a touching tribute.

Along with my mother, my wife, and my two children aged eight and five, I drove to Teen Murti House around 8 p.m. Nehru lay lifeless, his face somewhat puffed up. Next day, we watched the body carried on a gun carriage on its way to Shantivan. We stood on the lawns around India Gate, at almost the same spot as the one from which I had seen Gandhiji's cortege passing over 16 years ago. A memorable chapter in India's history had ended. We were not to see the like of him again.

A few days later, I saw a touching documentary produced by Films Division entitled "So to sleep." It showed a sick Nehru delivering his last public speech in Shanmukhananda Hall of Bombay. Many in the audience came out with the sad feeling that they had heard him for the last time.

© R C Mody. Published September 2019

****************************************************************************

The Day Nehru Died

Subhash Mathur is a resident of Jaipur after superannuation from Indian Revenue Service in 2007. Presently, Subhash is engaged in social and charitable work in rural areas. Subhash is also Editor of http://www.inourdays.org/, an online portal for preserving work related memories and human insterst stories.

ay 27, 1964. The day Nehru died. Where was I?

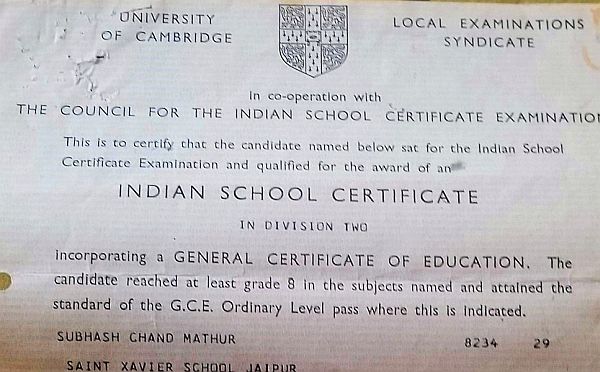

In the summer of 1964, I was in the final year of schooling at St. Xavier School, Jaipur. Those days, the 11thstandard was the final year in my school,with the Indian School Certificate exam slated for December.

My ISC certificate issued in 1965. Jaipur.

Thus the month of May was a nowhere time in that crucial year.

As usual, it was a hot and blistering summer. The Class of '64 was supposedly mugging and studying hard. But frankly most of us were just passing time. Having revised it repeatedly, the course material was beginning to look too dull.

During the summer break, the school library opened three days a week on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday for two hours. Mr. Hariram Asrani, brother of the film star Asrani, was in charge. My brothers Ashok Subodh and I eagerly looked forward to visiting the library to borrow books.

Once the book reading and borrowing was over, we would troop over the Jesuits' residence to join the social service volunteer group We also looked forward to distributing items like skimmed milk powder, wheat flour, old clothes, dried fruit powder like Tango, etc. in the poor bastis (settlements)' identified by the Jesuits.

The social service exercise was led by Fr. Wizbacher (Wilzy). The volunteers would gather near the Jesuit residence, and load the distribution material on the ‘carrier' of the bikes and paddles away. It usually took us two hours to return to the school. This was a good two-hour exercise out in the sun.

But Wilzy had a reward waiting for us on our return.

On return, Wilzy would throw open the school swimming pool for more than a splash. We could swim till we felt exhausted.

For me, these extra swimming hours became a boon. Not only I honed my swimming abilities but I also built up my stamina. I became a competitive swimmer.

Thus, it was the library, then social service. Followed by a swim. Back home: Then lunch. Dead tired, so sleep.

Most of the later afternoons went lazily at home playing Ludo, Carom, and Cards.

As I was an avid cricket fan, I would tune in to BBC to listen to the ball-by-ball commentary by John Arlot.

Then, one afternoon, our home phone jingled. It was unusual. Mr. Soni, PA to my father, was on the line. He conveyed the news.

That Panditji was no more.

Then, very quickly, the phone rang again. This time it was Mr. Siddiqui, my father's PA from the Ganaganagar Sugar Mills, a Government of Rajasthan enterprise, informing us about the death of Pandit Nehru.

The Ganaganagar Sugar Mills used to make alcohol, too!

It was a saddening occasion. Of course, it wasn't sudden. We all knew he that he was not keeping well.

But his passing away wasn't a thought that I ever entertained. Of course, the media had been speculating about ‘After Nehru Who? 'But that thought was far from my conscious mind.

Of course,his death set in motion a chain of events which no one had ever envisaged. His passing away continues to haunt us till this day.

Did Nehru's passing make any impact on me?

Of course, it did. Tremendously.

Those days it was simply unknown to me that people could die also. And that Nehru would not be alive to lead the nation.

I firmly believed that Nehru would go on forever with the Congress in the saddle. I used to get appalled with the thought that anyone would wish to remove Nehru as PM, and oppose Congress.

We in our family were happy with what Nehru was doing to transform India from an agriculture-based economy into a modern industry-centric country. But in the family, no one was willing to discuss the event. Why?

I can't recall the reason but perhaps the news had a sobering impact.

Otherwise, we were a garrulous and quarrelsome lot.

The next day, the newspapers reported the death in big headlines over several pages. The passing away of Nehru was viewed in terms of near disaster for India. And there was no clear front runner to take over his mantle.

And ‘After Nehru Who?' proved to be a question which remained unsettled for several decades to come.

But over the years, it became crystal clear to us that Nehru had laid a solid foundation for the emergence of India as a modern state.

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) as fashioned by Nehru. Tito, Nasser, and Sukarno told the world that big powers could not divide the world into just two camps.

Some nations could stay independent, and yet survive and prosper.

Even today, our national leaders say with pride that ‘no one can ask us from where we should buy our weapons from'.

This is NAM at its best.

The legacy of Nehru has survived some serious onslaughts, but his policies of industrialization and maintaining equidistance from the two post-cold war Blocks are still the guiding force for the nation.

Nehru may be reviled but his legacy is too difficult to shake off.

____________________________________

© Subhash Mathur. Published October 2019.

Comments

The day PM Nehru died

Add new comment