Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Keeping cool in Panipat

Category:

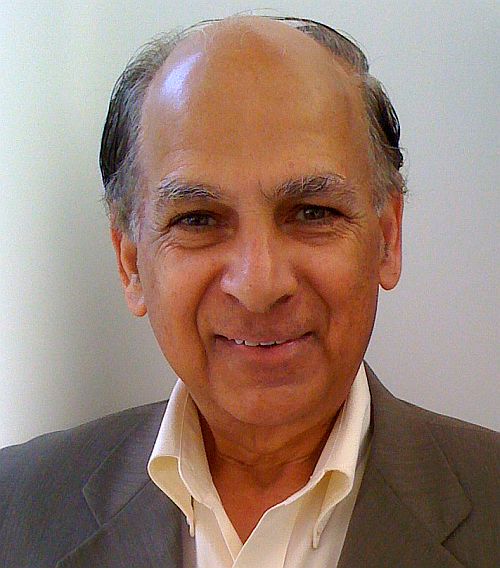

Dr. Juginder Luthra completed his MBBS from Medical College, Amritsar in 1966, and his MS in Ophthalmology from the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGI), Chandigarh in 1970. He moved to Nottingham, UK along with his wife, Dolly — a dentist from the Amritsar Dental College — and a daughter, Namita. They were blessed with twin daughters, Rohini and Rashmi, in May 1975. The family moved to Weirton, West Virginia in June 1975. Now their three loving daughters are married to wonderful sons-in-law, and Dolly and Juginder are blessed with six grandchildren.

When I was growing up, in the 1950s, summers were extremely hot in Panipat.

At that time, Panipat was a Tehsil in district Karnal, Punjab, and is now a district by itself in Haryana, India. The deep chill in December and January made us all pray for warmer weather. Be careful what you ask for! It would start warming up in February\; by May and June, the temperature would reach 100 degrees F and stay there, with bright sunshine glaring down every day.

We had a variety of ways to stay cool. Mercifully, none of us knew the words like air conditioner or air cooler - which we did not have. As a result, there was no problem of comparison at that time\; we face the problem now during our rare visits during summer, and most of our trips are in the fall or winter. Then, I don't recall anyone complaining much about the hot loo - burning hot air that hit the face when one stepped out of the shade of the house. No one knew what the temperature was in Celsius or Fahrenheit. We just said "Bhai, is saal tthaan kamal di garmi payee aye" (Brother, this year the heat is unusual). And we would say that every year. It was just hot, and everyone talked impatiently about the upcoming rain, which would cool the place.

Everyone would say "Is saal barshan late ho gayiyaan nein" (The rains are late this year). We all waited for the Monsoon, which would bring a wave of black clouds at the horizon, thunderously making their way towards us. The lightning and thunder were a signal for my siblings and me to run in, shed our clothes to bare minimum for decent public exposure, and then run out. Some younger boys came out totally naked.

Initially, the big splattering drops raised small plumes of dust from the parched ground into the air, making it emit an unforgettable, indescribable smell of the first rain. It was as if the thirsty, dry earth was saying "Thank you". The single drops, a promise of outpouring of water from the dark sky, sometimes led to nothing more than that. To the disappointment of all, the clouds would change direction, go elsewhere, and make someone else happy. We would feel sad, but knew that more were around the corner, and would be here soon. When they came, no one cared or even knew about the side effects of lightning strikes. We were out in droves in the open spaces and streets and soaked the sheets of water falling from the dark sky.

It seems like it happened only yesterday. Soon, the open naaliyaan (open sewer lines) are overflowing. Small brown rivulets have formed giving birth to large puddles and ponds. Swirls of black clouds, accompanied with an orchestra of thunders preceded by lightning flashes, which look like dancing branches playing hide and seek, let loose the much appreciated water. All the children and some adults, for hours, run around in the water. Even cows and buffaloes take dips in the ponds to cool off. To our amazement, dogs are swimming in the pond. They come out, shake their heads, spraying water around them to dry out. But then they jump right back as more have joined the group.

We would have prepared paper boats, later made famous in a Jagjit Singh's song, well in advance of the first rain drops. They were now ready to float. We would let them loose, and run after them amidst sounds of thunder and laughter. We caught them, emptied out the pouring water from the boats, and let them float a bit longer. But then the undulating waves and rain drops overpowered them. We waddled out, dripping water into the house, picked up the remainder of the boats and started the fun all over.

PitaJi, my father, was ready with bucketfuls of washed choosa mangoes. Getting soaked in the rain or standing under the open roof spout, parnala, in the central part of the house, we rolled them in our hands to loosen the pulp, bit out a small piece on the top, and sucked out the pulp. We did not need knives. The ones with faster hands and mouths got to eat more. The four brothers and their happy father devoured them, throwing back the pits and skin in the flowing water. One such pit later took roots and became a source of future supplies. The mangoes vanished quickly, prompting PitaJi to run in and bring more from the house, till none was left.

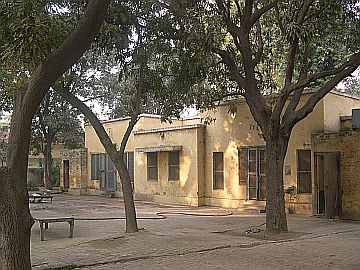

Luthra home in Panipat, 1950s.

Eventually, MataJi, my mother, would call all our names as a one liner - "Vey VirinderKrishanGindiShoki, hun andar aa jao, garam garam Poorhe te kheer tayyar aye" (Hey Virinder, Krishan, Gindi, Shoki - come in now. Hot poorhe and rice pudding are ready").

We all ran in, took a quick shower with the water, carefully saved in the large oval galvanized iron tub and several metal buckets. Water from the taps used to come for one hour in the morning and one in the afternoon. We would leave the tap in the open position. At the first intermittent hissing sound of air coming out ahead of the precious commodity flowing through, we ran to the three tootiyaan (faucets) in the house. We filled every container of every size and shape with water. We scheduled bathing in the cold water around the times when it bubbled out of the faucets. Large water storage tanks on the roof tops and motor pumps to transport the water up came much later.

We saved water in the containers for later use, such as the one now required, before the kheer and poorha, which we enjoyed in the open veranda, watching the rain gradually stop. It was amazing how all the puddles and ponds got soaked up quickly by the thirsty land, plants, and trees.

On lucky days we got hot jalebis purchased from local sweet maker, Bosa Ram. We never had to pay him any cash. Unknown to us, he kept a running account book in a long red cloth covered ledger, for us as well as all the people living in our mohalla (neighbourhood). At the end of the month, PitaJi paid the bills. We grew up thinking that Bosa Ram was such a generous man giving away free sweets. He actually was a sweet man, always smiling and handing out a freebee or two to us, especially boondi ke laddoo on Tuesdays, the day of god Hanuman.

The first rain was a matter of rejoicing. The school principals would declare this day as a Fine Day. He declared the school closed. "Children, it is a fine day. You can go home, enjoy the rain and have a fine day." These were melodious words to the children. They hurriedly packed up their bustas (school bags), and ran home. There were no school buses, no pick ups, no telephones to alert the parents. It was completely safe for everyone. All the children, noisily, ran or walked home. On later rainy days, children would plead "Principal sahib, it is a Fine Day, may we go home." Depending on his mood, children ran out with glee or sulked and stayed in school.

The abundant water transported by the clouds brought joy to all living objects. Life is a double faced coin, pleasure and pain run side by side. Occasionally we heard about someone drowning, some areas got flooded by overflowing rivers and creeks. There were no dams to regulate the ocean being unloaded on the land. We never faced such life changing calamities, but had our share of minor annoyances. The solid appearing concrete roof of our house was obviously not water tight. Water dripped inside all the rooms from the lowest parts of the uneven ceiling. We hurriedly moved around our precious furniture of 10 wooden chairs, a table and two beds. What could not be moved, got covered by plastic sheets. We strategically placed all available containers, large and small, to catch the drips. Everyone was running in and out, emptying the rapidly filling containers.

Finally the clouds declared the end of their show by the appearance of seven coloured rainbow from one horizon to the other. Panipat is located on flat land and there is nothing to obstruct the display of nature's panoramic display of receding clouds, a hazy sunshine and colourful display of all its colours in the semi-circular rainbow.

The cool air stayed for a while. Then the heat, along with the newly added humidity, returned with a vengeance. Constant dripping sweat kept our cotton shirts and knickers (shorts) wet. We replenished it by drinking cool water dispensed from the wide open clay round container - gharha or matka, and from narrow long necked clay containers - surahi. We had a wooden stand that would hold three of these containers. Their openings were carefully covered with a steel plate, inverted katori, or cloth to protect the drinking water from the dust and thirsty flies. Being made of porous clay, they were natural water coolers as well

A daily dose of Shikanjvi (lemon drink) was a must. We used freshly picked lemons from our own garden, or the ones purchased from the stores, to make the sweet lemon drink with the cool water. The young hands struggled to press the flat handles of a wooden lemon squeezers. We were thrifty. The squeezed lemon pieces were again stacked in the squeezer to get the last drop out. We were generous with sugar to dilute the tangy taste of lemons\; some people added a pinch of salt as well.

In the verandas and windows, we hung Khas Khas chick, sometimes called Tatti. We always laughed and wondered why such an aromatic mat was given such a paradoxical name. This was made of a breed of grass that grows downwards, and can attain a length between 6 to 8 feet. We filled buckets of water, which we poured on the top of the chicks, letting it trickle down. The one in the veranda had a cloth border with a rope attached at one end. We took turns to sway it back and forth, letting air filter through it and bring the cool fragrant air inside. The ones in the windows depended on the flow of breeze. These were our natural air coolers.

We kept ceiling fans switches in the on position all the time. But it did not mean that the fans swirled all the time, as it was common to hear "Lao, bijli fir chali gayee aye " (There, electricity has gone again). Electricity ran through the wires intermittently with random interruptions. "It is gone more than it comes" was a common complaint.

As a backup, we had several ornate, rectangular or rounded, hand held fans made of woven cane strips attached to sturdy polished wood handles. Each one had different pattern of cloth border. Cheaper varieties without cloth border and flayed borders were also available. Children happily swayed them for themselves and also helped the elders as the swirling motion of their fingers or wrist could easily tire the old hands. In addition to providing movement to the air, these fans kept flies at bay.

We never stopped playing outside, despite the heat or even the hanerian (dark dust storms) that made their appearances in the weeks leading up to the rainy season. There were many trees on our street, providing us the much needed shade to play Bante (marbles). Other games such as Piththu, Guli danda, and Cricket were saved till the air cooled down a little, as the orange sun moved towards the horizon. Three months of summer vacations from school did provide us plenty of time to play.

We wore one of the two cotton white shirts and knickers we all had or shared. We wore one and MataJi, with regular help from a lady, Ganga Devi, washed and dried the other. Our mother was always busy, mostly washing clothes and cooking.

We took short baths two or three times a day to wash off the dust and also to cool down. In the absence of running city water, we drew water from the two hand pumps in case all the containers were empty.

Street vendors were busy selling baraf de gole, shaved crushed ice balls, covered with multi-colour sugary syrups. Depending on how much money was left over after buying the essentials, we sometimes indulged in this luxury.

The vendors also sold frozen kulfi in conical metal containers, which were stored in ice filled drums. It came in plain variety or one mixed with pista (pistachio). Spaghetti shaped Falooda was placed over the kulfi. It made a delicious cold combination.

Some street vendors sold carbonated soda drinks, dispensed in ice chilled glass bottles. These were too expensive for our family. I might have tasted the sweet soda water only once. The gas was held in check by a marble size glass ball in the narrow neck of the bottle. The ball was pushed down using the thumb with force. Once, a bottle burst under high pressure, and a friend of mine lost his one eye due to the injury from broken glass.

Making ice cream was a highlight of the summer. Amongst many other luxuries of life which our elder brother, Prem, brought home, everybody loved the ice cream maker. It was a wooden drum with a metal container inside. The revolving blades inside the metal container were attached to a handle through a couple of gears.

Making ice cream was a big production. MataJi boiled milk, mixed with cream\; later sugar and Kesar was added. Sometimes we had the luxury of adding cut pieces of almonds or pistachios. When the mixture had cooled, we poured it into the container. In the meantime, one of us pedalled our bicycle to the ice cream factory located about 2 miles from home (it seemed much farther than that). We purchased a slab of ice, wrapped it carefully in a sheet cut out from a jute bag, and tied it securely to the carrier of the bicycle. The return journey was brisk, lest all the ice should melt. Slow drips of water were incentive to pedal harder.

The team at home was ready with a metal hammer to quickly crush the wrapped ice into small pieces. These pieces, along with sprinkling of large salt granules, were placed between the metal container and the outer wooden wall. Impatiently, we would start rotating the handle, adding salt and ice, as it melted and oozed out through the slits in the outer wooden container. Initial rotations were easy and were assigned to the younger children. The more muscular older children completed the job.

Anticipation grew as the rotations became harder. When rotating became almost impossible, this was a sign that the ice-cream was ready. Now, we all had watering mouths. The lid of the container was opened, and a water laced spoon, later replaced by a round one with a release handle, took out the ice cream. We all had katoris and spoons ready on stretched out hands. "Thodhi hore de de na" we all requested. We relished it, ate it quickly to get a second helping and also before the heat melted it down to milk. Vanilla was our favourite flavour. Almost always, we argued about who would scrape the bottom portion of the container. We turned the container upside down to let the last few drops trickle down into our thirsty mouths.

Sardai was another drink for the summer. We made it mostly when PitaJi came home for a couple of days from his job at the out of town brick kilns. Water soaked, peeled almonds\; cantaloupe seeds and black pepper were crushed in Dauri Sota (mortar and pestle). Dauri was made of stone, and Sota was a round smooth log of wood, 3 to 4 inch diameter and about two and a half feet long\; it was sometimes used as a weapon during the sibling fights. The crushed powder was put in a jug. We added water to make a paste, and then added more water, which converted it into a drink. This was filtered through a thin muslin cloth. Sugar and cool water (ice-- if available from Bosa Ram), were added and this made a wonderful drink in the hot days.

Another way to stay hydrated was to eat fruits rich in water. A large watermelon, weighing about 30 to 35 pounds, was kept in cool water all day. In the evening, the whole family sat together and ate it all. There were no refrigerators to store the left overs. We ate cucumbers, considered Thandi Sabzi (vegetable that cools you), every day. We cut the top and rubbed it against the bare surface of the remainder for several minutes\; white foam erupted from the main body of the cucumber, which was wiped away. This was supposed to remove the bitterness out of the cucumber.

The sun would finally set. Preparations were made for a comfortable sleep. Tired bodies needed it to revitalize and face the next hot day. All of us slept outside in the yard. All the children sprinkled water (Taraai) on the dry parched ground as well as the brick lined large yard. We carried buckets filled with water which we sprinkled by hand, half on the ground and merrily half on one another. The water would settle the dust and cool the hot grounds. The family laid out several charpais, four legged beds made out of jute or nivaar (crisscrossed wide cotton bands). A pillow and two sheets made up the bed.

Mosquitoes used to wait for the victims. In our defence, we would put up Machchardanis, mosquito nets. Two bamboo sticks were anchored in the shape of an X at the two ends of the bed. We tied the mosquito net to the bamboo sticks using the attached cotton strips in the four corners. The edges were carefully tucked under the sheet. Even a small opening meant listening to the swirling sounds of mosquitoes, as if alerting us to get ready for the bite.

The night time temperatures dropped quickly. A glass of ice cold milk, sometimes with jalebi or bread, would be the night cap. "Don't forget to rinse your mouth", ever vigilant MataJi would say, and we obeyed. We did not brush our teeth before sleeping. A vigorous swishing and rinsing was a must. Laying in beds, side by side, we talked of the day's events and made plans for the next. Exhausted bodies went off to sleep, and woke up to the sound of roosters and feeling of heat from the sun.

It was going to be another nice, hot day in Panipat, and we were ready for it.

______________________________________

© Juginder Luthra 2015

Editor's note: I approve all comments written by people. The purpose of approval is to prevent unwanted commetns, inserted by bots, which are really adverstiments for their products.

Comments

Add new comment