Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

My School Days at St. Paul’s and Burma through Turbulent Times

Category:

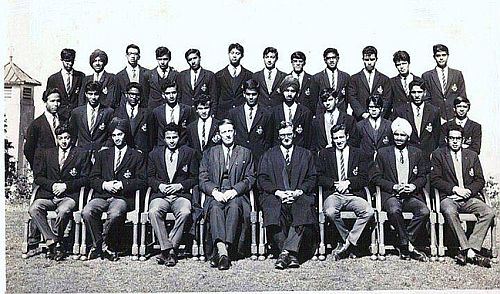

Gautam Banerji has a Master's from St Stephen's College, Delhi, an LL.B. from Delhi University, and an M.Sc.(Econ) degree from the London School of Economics. He taught at an undergraduate college in Delhi, 1973-85, and worked for UNICEF 1985-96. Then he moved to London to practice law. He served as the Judicial Advisor to the Judicial Development Institute, Baghdad, 2009-10 as a U.S. government contractor. He was a member of Commission for Sustainable London (2007-13). He continues as a Trustee and Board Member of Hindu Council, UK. Now fully retired, he lives in Dilijan, Armenia, with his wife, who teaches at United World College, Dilijan.

I was eleven years old when my father decided that my English was not English enough. So, he decided to send me to St. Paul's School Darjeeling to be groomed into a gentleman in the best of English public school tradition. In those days, St. Paul's was rated as Eton of the East, served by Scottish matrons and Irish nurses while Oxbridge graduates were tasked with ‘educating' young Indians for higher aspirations in life.

Moniti Meliora Sequamur ran the school motto: having been taught the higher ways, we followed. And the school song echoed much the same sentiment: "From the low and steamy plains, upward the old school calls!" rising to a crescendo with "Upward the old school calls, St Paul's! St Paul's! St Paul's!"

St. Paul's School, Darjeeling, (taken from the Upper Field) with the Kanchenjunga as a backdrop on a bright sunny day.

St. Paul's after a snowfall: taken from the school quad. The two windows on the extreme left were where we met for our Form II classes with our dormitory, Cotton Hall, on the upper floor. We completed schooling at Form VI\; Form II would correspond to Class 8 by present day Indian schooling, or Class 7 by our schooling, which we completed in 11 years, and not in 12 years, as presently. School leaving year in the UK is still called Form VI.)

Leslie Goddard retired as Rector at St Paul's in 1964 after thirty-six years of meritorious service to the Empire. He earned his OBE in the process while I was there. David Gibbs took over and continued after I had graduated. Both were stalwarts in their profession. Both were Cambridge graduates. Jim Clarke, from Oxford, taught us English. A bit eccentric and a bachelor, he was nonetheless an excellent teacher. Billington continues to attend our Reunions in London. He was a young teacher when we were at St Paul's.

David Gibbs is too old to travel to London now. We see the next generation of the Goddards and the Elloys at our Reunions today. The alumnus in London runs to over two hundred in membership, many now in the eighties. We even had an Old Boy of ninety-four at our Reunion recently.

David Gibbs (center), with his daughter, accompanied by Leslie Goddard, climbing up the steps of the school pavilion to witness a cricket match\; circa 1964, St Paul's Darjeeling on transition from Goddard to Gibbs as Rector.

I remember in late February 1962 my father accompanying me to India from Rangoon to put me in St. Paul's. Even while I was at the Methodist English High School in Rangoon through my primary school, I knew I would have to leave for St. Paul's someday. The two sons of Mr. R.N. Burjorjee, Rustam and Sarosh, were already there. Mr Burjorjee, himself a successful lawyer like my father, had preceded my father as the President of the All Burma Indian Congress. Mr. P.M. Bose's three sons, Ronald, Donald and Skinny, who were several years senior to me, had already completed their schooling when I arrived in St. Paul's. Mr. Bose was a leading stevedore and stood in as a guarantor at the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank in Rangoon for leading businessmen those days. My father's classmate in school, Dr C.C. Dey, had also sent his son to St. Paul's. Helen, his daughter and a few years my senior, studied with me at Methodist.

Methodist English High School (MEHS), Rangoon, 1960s as it looked in my primary school days.

At a Children's Day event, circa 1958, USIS Library, Rangoon, with me in the extreme left front row. I was then a student at MEHS Rangoon.

It was the aspiration of all successful Indian families in Burma those days that their sons would make it to St. Paul's, as the school opened up to receive Indian students with India's Independence. The aspiration of the middleclass Indian underdog to be more English than an Englishman continued with unabated pride.

St. Paul's is the oldest surviving hill school in India, run very much on the lines of an English public school even today. It will be celebrating 200 years of its existence in 2023. Prior to 1947, St. Paul's catered to the needs of British civil servants, expatriates serving in India under the colonial Raj, and for a very few selected feudal Indian families. With Independence and under Leslie Goddard, the school started attracting students from South East Asia and the Far East as well.

It was the only truly international school those days offering both the Cambridge O and A Level degrees. There was a sizable crowd from Thailand and Burma who attended St. Paul's in my days besides students from Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim (which was still then an independent state) and a few from Indonesia and Japan as well. The Sikkim Chogyal's two sons were junior contemporaries of mine at St. Paul's till the father, after his marriage to an American lady, Hope Cooke, moved them to a public school in the UK.

I recall while my father was still in Darjeeling, having just brought me in for my admission at St. Paul's, when we woke up to the alarming news of a military coup in Burma on 2 March 1962. He had to rush back to Burma leaving aside a few things that needed tidying up in Calcutta before his departure. My mother and my sister were alone in Rangoon, and he was concerned despite the care of friends and the community.

The initial news was alarming enough. U Nu, the democratically elected Prime Minister, was put behind the bars along with his cabinet. U Nu had attended the Law College with my father. Dr E Maung, a senior cabinet member and a learned jurist, was their law Professor in their college days and he was similarly incarcerated along with U Raschid, another cabinet minister and a contemporary of my father at the Law College. He had spearheaded a student movement in his days along with Aung San, the father of Aung San Suu Kyi. My father knew them all too closely. Now, they were enemies of the State. The judges of the Supreme Court were also similarly incarcerated without trial.

Although the timing of the coup and my move to St. Paul's was a coincidence, I liked to believe that my father had a lurking suspicion it was about to happen, and he moved me to the safety of St. Paul's to avoid dislocation to my studies. Anyhow, the year1962 did not seem to augur well with us at St. Paul's either. We had to be rushed back early to our homes soon after the Puja break in October on account of the Sino-Indian border conflict. The positive side to it was I could return home to Rangoon for a longer vacation before the school reopened in early March next year.

The contending claims of China and India were no doubt hard for us to comprehend as young schoolboys. A disputed Himalayan border was the main pretext for the conflict, we were told, but of course other issues must have played a role as well. There had been a series of violent border incidents after the 1959 Tibetan uprising, when India had granted asylum to the Dalai Lama. In my first year at St. Paul's and through frequent visits to the town on weekends, I had come to believe that the local Tibetan community was a part and parcel of life in Darjeeling. We heard of their recent dislocation from Tibet but knew little of where they came from.

My curiosity about Tibet and its people made me choose a recent publication, The Third Eye by Lobsang Rampa, for my academic achievement prize the next year. The book, published by Secker &\; Warburg in November 1956, was popular reading those days. We thought a Tibetan monk wrote the book. On investigation the author was found to be a British plumber named Cyril Henry Hoskin (1910-1981), who claimed he was possessed of the spirit of a Tibetan monk named Lobsang Rampa. The book is considered to be a hoax now although I still continue to preserve it with pride among the few that have survived with me through frequent moves in life.

As I grew through my schooling and childhood, I began to better understand other contending claims of Indians and the Chinese in the region, including Burma. In our childhood, the old grid-patterned colonial city of Rangoon was almost equally divided between Indian and Chinese landlords. The Burmese confined themselves to the comforts of their country homes, much like the provincial Englishman. Trade and enterprise moved the Chinese and the Indians to settle there and spread a busy cosmopolitan landscape across urban Rangoon. It was this Rangoon that I loved to return to for my long vacations during the few years that I could visit Burma after I moved to St. Paul's.

After my first year at St. Paul's in 1962, I could continue to visit my parents in 1963 and 1964 through my long winter vacations. However, life in Burma for the expatriate communities started becoming more difficult thereafter. I could see it happen on my visits even as a child.

After I left in early 1965 for the new school term, I could not visit home through my last two years in school. This problem continued through my undergraduate days at St. Stephen's, Delhi as well. I still recall waiting patiently for my Entry Visa to arrive each year from my father in Burma. It never did. Ultimately, I began to accept it as a reality I had to come to terms with.

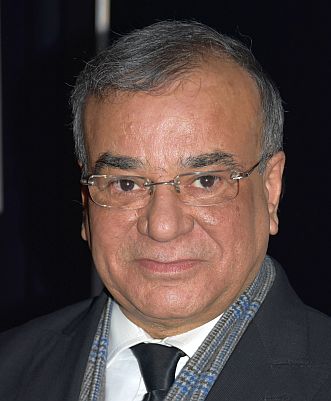

Speech Day, 1963, St. Paul's, Darjeeling. I am receiving a prize from Shrimati Padmaja Naidu, Governor of West Bengal. Mr. Leslie Goddard, Rector, seated in the background. Mr. Elloy, the Headmaster is handing over the prizes assisted by Mr. Payne.

Sports Day, 1963, St. Paul's, Darjeeling. Finishing the 100 meters sprint in the third place. Mike Nolan led the way as always. He was in my House (Clive) and trained with me. Chris Vyse is in the second place.

Speech Day, 1964, St. Paul's, Darjeeling. I am receiving a prize from the Chief Guest, Principal of St Joseph's School, Darjeeling, assisted by Mr. Mehta.

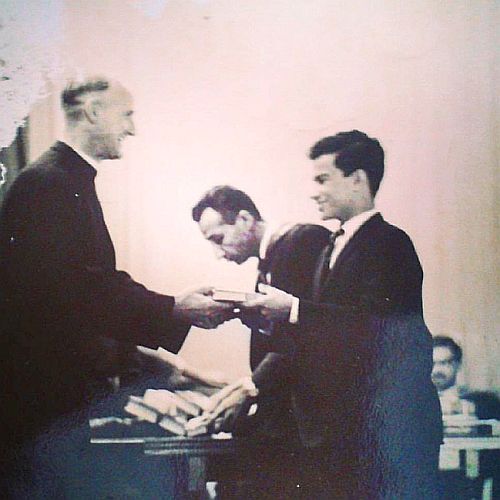

Speech Day, 1965, St. Paul's, Darjeeling. I am receiving a prize from the Commissioner of Darjeeling, who was also a School Governor, Mr. Ezra assisting. Seated in the background, left to right, are Mr. McDonald, Mr. De Young and Mr. Dutta.

At the finishing line of the School Marathon. Probably 1965.

Speech Day, 1966, St. Paul's, Darjeeling. I am receiving a prize from from Major-General "Monty" Palit, himself an Old Paulite.

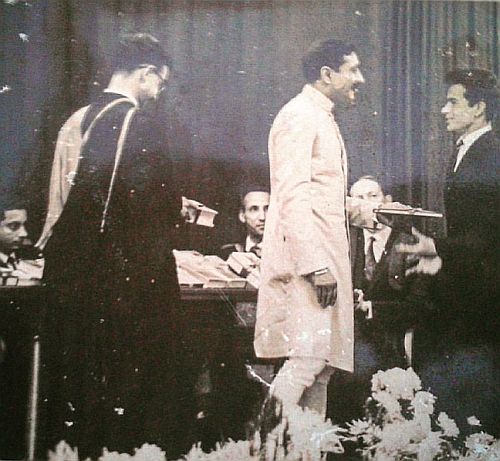

Our Form VI (school leaving year) December 1966.

L to R Seated: C. S. Pyne, J. S. Gulati, S. K. ("Pointy") Ganguly, Mr. J. Clarke, Mr. French, Mr. R. Marshall, Dhanwant Singh, Rajiv Datt.

L to R Middle row: P. Ray Sarkar, N.P. Bhattacharjee, Sanjoy Bhattacharjee, Rathin Sinha, Gautam Banerji (me), U. H. Khan, S. P. S. Narula, Naresh Kukreja, A. J. Kundu, N. Wadhwani, P. S. Biswas

L to R Rear row: S. K. Gulati, Lali, S. Contractor, Amitabh Khemka, P. K. Swaika, D. K. Kundu, S. M. Pyne, A. K. Ghosh, A. K. Roy, Donald Shaw, I. J. Thapa, D. Dhara

St. Paul's was a world apart from what I had experienced through my primary schooling at MEHS Rangoon. I still recall the exhaustive list of ‘outfits' that the school sent my father to purchase and prepare me for the new life I would soon lead. We had four pairs of black shoes, one of which was toe capped for wearing on Sundays with our blue three-piece serge suits. On weekdays, we wore coarse grey English tweed suits, two piece of course. The suits had to be tailored at Phelps Outfitters, located opposite the Great Eastern Hotel, Calcutta.

Phelps, the grand old English master-tailor and outfitters for St. Paul's, used to make regular visits to St. Paul's from Calcutta in those days to take the measurements. It was much later in life that I began to appreciate and understand this typically English obsession with outfits. Everything fitted in with the ‘role-play' through life. English traditions survived on histrionics with loads of pomp and ceremony. The best of it is to be witnessed in the English courts of law and the Parliament.

Discipline was taught through a strict ‘carrot and stick' policy, much the way you groom your pet dog, I suppose. There was a reward for every achievement and a punishment for every transgression. The School Captain served much like the regimental Sergeant Major along with his team of School Prefects. They were tasked with disciplining the kids into young adult life. Leo Lucas with his loud voice and stern demeanour was perhaps the best School Captain we had in my days. I still meet him at our Reunions in London these days, where he is settled like many of us. He is a mellowed old man now but still turns up in his School Captain's hat, which he has preserved with pride.

The School Captain's hat was somewhat different from ours, with red stripes and a ‘tail' hanging down from the top. We wore modest ones without stripes and tails\; we had to wear them with our blue serge suits when we made visits to town on Sundays. An umbrella was also an essential part of our dress code. It had to be carried at all cost. It was also essential to take off our hat and wish our senior if we encountered one on the streets of Darjeeling. He had to wish us in return and in a similar manner. We could be punished if caught by a Prefect in breach of this essential etiquette of good breeding. We were no less English, after all!

It was on Sundays alone that we polished our shoes and tidied up our beds and lockers for inspection by the Rector in person accompanied by the Head Master and the matron. The rest of the week it was all done for us by the retinue of support staff in our dormitories. We even had a tailor who sat with his hand-machine in the dormitory on weekdays for the odd mending and stitching. The school had its own laundry. We deposited our soiled clothes twice a week in the huge laundry box in the presence of our matron. These were in turn collected and sent to the laundry. They returned to be stacked away in the ‘linen room' by the matron, and to be issued to us twice a week.

We bathed twice a week in the good old English tradition and in the bathtub with hot water. This in our younger days had to be done in the presence of our matron, who presided over the whole ceremony. Some of us felt a little shy to shed our clothes before her prior to plunging into the bathtub but we soon overcame that coyness and learnt to revel in our nudity. Boys past puberty lived in separate dormitories, and they were spared the matron's glaring eyes on bath-days.

The day began with the ‘rising bell' at six. We had to rush down to the dining hall for chhota hazri (a small, early morning meal) after tidying up. It was a humble cup of tea with two biscuits\; the purpose was to warm us up for Physical Training (PT) that was to follow in the Upper Field.

Our Prefects led us for the PT for half an hour. Then came, morning prayers in the school chapel. The first lesson of the day followed soon thereafter, and then we went in for breakfast at eight. Normal lessons continued till lunch with a break between eleven and half eleven. It was at this break that the ‘naughty ones' lined up in the Lower Field under the supervision of the Prefect on duty for Punishment Drill (PD).

I made it frequently to PD on account of minor breach of discipline like talking before grace at meals, chatting loudly during the long drawn sermons at Matins on Sunday mornings at the school chapel, using swear-words or speaking in a language other than English. The last was a severe transgression. We were often reminded that our parents had sent us to St. Paul's to learn good English and good behaviour, which in conjunction sounded complementary, one meaningless without the other. We learnt that English was the chosen language for polite conversation and without being offensive.

All games were compulsory, and the major field games were played by season. These were played after lunch in ‘sets'. Those that did not play on a particular day went for runs to prepare for the annual Marathon. Although I played cricket, I never excelled in it. Rather it was too gentlemanly for my temperament. I found it too long drawn, and could not connect with it. It bored me. I was a sprinter and ran the 100 meters and the 4X100 meters for my House. On the football field, I played in the wings.

Les Goddard, who had a love and passion for sports even in his old days, often came up to watch us play on the Upper Field. It just happened to be one of those days, cold and wet and misty, when I was playing in the wings, and Goddard was nearby, unnoticed by me. I yelled out a swear word and heard his husky voice just behind me: "Who was that?" he asked. I put up my hand. He called me out of the field, and packed me off to his office with the admonition: "I'm sending my best man to give you four or six for that!"

I knew who his best man was and what I was heading for. P. Chand, a bulky man of six feet three and a retired Chief Petty Officer in the Indian Navy, was our Physical Instructor in those days. He soon arrived and led me into the Rector's office. I bent down to receive my four on my bottom and could hardly rise to say, "Thank you, sir," for it when he said: "Bend down again, I have to give you two more!" That was what we called "six of the best" those days and was reserved for the serial offender. The pain and agony lasted for over a month, and my bottom became a showpiece for others to empathise on at our "bath-days".

I went through a steep curve to be disciplined. Those marked out twice for PD on a single day were called "twicers" and had to meet Mr Elloy, the Head Master, for a pep talk and counselling after lunch that day. Depending on the severity of the offence, the student could be caned as well.

It just so happened that I was a "twicer" for four consecutive days in a single week. On the fourth day, which was a Saturday, Mr. Elloy gave me a long counselling session in his office, repeating: "You're a bright boy. You do so brilliantly in classwork. You walk up to our pride on Speech Day to receive prizes. Why can't you make the effort to be disciplined?"

I nodded and promised to make the effort. The next day, when Mr Elloy came up for our Sunday inspection with Mr Goddard to our dormitory, he pointed me out to the Rector as a "serial offender" and cautioned me: "Remember, I want to see less of you!"

But, I was a "twicer" again the next day!

So much for the punishments\; now for the rewards. I did mention that on Sundays we had to put on our blue serge suit and wear our toe-capped shoes. We had to be in our Sunday best for Matins after the Rector's inspection in our dormitories. It was the Prefect's pride if we turned out well, the shine on our shoes included. We cleaned and polished our shoes on that day with special care. In fact the rest of the week, it was done for us. The Prefect rewarded the boy with the best shoeshine the next day at breakfast. This was by way of a thick toast with a liberal amount of butter almost soaking through it. Only the Prefects had the privilege of being served toasts for breakfast\; and of course the best shoeshine boy on Monday mornings. The rest of us had to do with simple slices of bread and butter.

We often got into rowdy bouts with each other through minor differences on issues. When the differences could not be resolved verbally, we challenged each other to fight it out behind the gym. "Come behind the gym," was not a threat but a show of chivalry. As disciplined boys, we never fought physically anywhere else. These were the traits of a good Englishman, we learnt. Often we returned from the fights with a tell tale sign of a black eye or a bloodied nose. It often required visits to the school infirmary for more serious injuries. These were all a part and parcel of the process of growing up into manhood, we supposed.

What we missed the most at St. Paul's were the girls. I grew up through my primary school in Rangoon with both girls and boys as friends. Although the town had Loreto Convent, a school for girls, it was run by Catholic nuns and I guess they never trusted their girls with the Paulites. There was also a St. Joseph's School in town run by the Jesuits. The Loreto girls went to the St. Joseph's socials, and not to ours. Those that made to our socials were the daughters of army officers posted in the army barracks further up the hill from our school at Katapahar. Often, they were several years older than we were. That was the best we could hope for, and we had to remain happy.

I did mention that after my visit to Rangoon for the winter vacation of 1964, I could not make it back to Rangoon for the remaining two years in school. This was the first time I went to spend my vacation with my grandparents in their country home in Mandalai. Prior to that, we used to transit through Calcutta in school groups, stayed for a night at the Great Eastern Hotel, and took the flights to our overseas destinations the day after. My grandpa used to travel up to Calcutta from Mandalai to meet me at the hotel. Despite my grandma's wishes, she never got to see me while I was on transit in Calcutta.

Mandalai was a world apart from my "English life" in St. Paul's. It was here for the first time perhaps in my childhood that I started to experience life as it should be. My Bengali was poor but was adequate enough for my nani (grandmother) to comprehend. The transition from toe-capped shoes to running barefoot in the paddy fields, climbing trees and bathing in the village pond was one big delight. It was here also that from my grandma, I came to learn of the many interesting family lore.

Although the hospitality of my maternal folks was overdone and overwhelming in my mother's absence, my nani and my aunts continued to play the role of substitute mothers. Both my aunts, who were unmarried at that time, taught in the village primary school. The school was very different from what I had known and experienced schools to be till then but getting to know how they were run and who taught and studied in them became a part of my essential education. It took me through my career with UNICEF in my work with distant and remote communities later in life.

Besides Mandalai, I spent some time with my mother's two uncles in Birbhum, close to Shantiniketan. Both were retired and both were bachelors. They were my grandfather's younger brothers.

One of them, Dhirendra Nath Mukherjee, was a lawyer and a Swadeshi in his younger days. He was an avid traveller and turned spiritual in later life. He finds mention in the travelogues of Uma Prasad Mukherjee, who was a close friend in his travels and a relative. Uma Prasad was a brother of Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, the nationalist leader of those days, who was incarcerated by Nehru soon after Independence for his spirited right-wing political leanings.

My other grand-uncle, Lakshmi Narayan Mukherjee, was a retired police officer who held several key assignments with the Special Branch of the Intelligence Bureau through the Raj and soon thereafter. This included an assignment in Dacca (now Dhaka) in the days just preceding Independence.

We lived with him in his sprawling apartment at 8, Ashutosh Mukherjee Street in the heart of Calcutta when we arrived on vacation with my mother from Rangoon in my early childhood. We then made it to other destinations from there, including visits to Mandalai. This was before my St. Paul's days. Upon our arrival at Dum Dum, the security at Immigration having been alerted in advance by him whisked us away on priority before others. As a child, I thought that was the norm.

The two brothers were very different in temperament but together they were a delightful pair in retirement. Both loved me dearly through my childhood, and were delighted to have me with them for part of my vacation.

The idyllic charm of the Bengal countryside was preserved in its pristine glory in what came to be known as their "forest retreat" in Dhanyagram, on the banks of the Mayurakshi, which they called their Tapovan. It was here that I learnt to handle my grand uncle's ‘404' rifle, which is now an obsolete bore of vintage value. It was here also that I discovered more of my mother's extended family and her many family connections. Nirad Gopal Mukherjee of Bakulia House and the then owner of Inchek Tyres built a beautiful country house close to my granduncles and came there from time to time for a change from his busy business life.

By the time I was finishing my schooling at St. Paul's, Prof. Devaprasad Guha, who was a Pali-Buddhist scholar of repute and was assigned to Rangoon University as a Lecturer on contract with the Burmese Government through the 1950s and the 1960s, had returned to India. He was proceeding to Delhi University with a Senior Research Fellowship in Buddhist Studies. He was to live in Gwyer Hall on the University campus, close to St. Stephen's College. My transition to Delhi was motivated to a great extent by Prof. Guha's presence there. He was more than a friend to my parents in Burma. He looked up to my father as an elder brother.

I moved to St. Stephen's College, Delhi in July 1967 for my B.A.(Hons) degree in English, with Prof. Devaprasad Guha as my local guardian.

Devaprasad Guha, despite his scholarship, was a somewhat timid man. It was his brother, Ranajit Guha, who made an impact on me in my college days, when he was invited to Delhi University as a visiting Professor. He was teaching at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London in those days. Prof. Ranajit Guha, was a senior contemporary of Amartya Sen and was renowned for his pioneering work on the Bengal Famine of the 1940s with the perspective of a historian, before Amartya Sen attempted his analysis from the perspective of an economist. Both knew each other closely. Through his short tenure at Delhi University, Ranajit Guha inspired many renegade socialists of the day through his inspiring scholarship and thinking. I was no less inspired.

Despite the distance that began to grow on me through this long separation from my family, I continued under the protective care of an English public school with English matrons meeting our pastoral needs alternating with the rural charm of the Bengal countryside through my long vacations. The transition was severe but I learnt to revel in it.

In 1970, when I had got my undergraduate degree, I was able to bag an exchange scholarship to Keio University, Tokyo. One reason I was keen to get this scholarship was that I could visit my parents for a week on a tourist visa on my way to Japan, and for another week on my way back in 1971. That was the longest the Burmese authorities would allow me to visit what was my legitimate home.

It was only in 1975 that we as a family could finally be reunited when my parents and my sister moved to India.

______________________________________

© Gautam Banerji 2017

Add new comment