Number 2898, Saraswatipuram

Category:

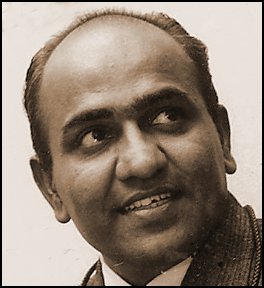

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

I have no ancestral home. I never had one. My forefathers belonged to a village called Tambarahalli, in the ashtagram cluster of villages in the Kolar district of Karnataka.

My grandfather moved home from there at some stage to another ashtagram village with the very impressive name Devarayasamudram, which literally meant ‘an ocean called Devaraya’ or ‘Devaraya’s ocean’. It is in fact a dry, land-locked village with no ocean in sight anywhere near. The seashore is as far as Chennai, some 300 km away. But it has a rain-fed lake, the main sources of water for the farmers. It was in Devarayasamudram that my father was born. It is also the place where he built a house, which he had to sell later to raise funds for my eldest sister’s wedding. The house still stands there in a modified form. Devarayasamudram is in fact my ancestral village.

If the “home is where heart is”, then

The family lived in this house during my school years. My father was posted as the doctor in charge of the government dispensary at Nazarbad, a locality close to the Chamundi hill, the last posting in his service. He used to peddle all the way on his bicycle for work. The house was too small to hold our enlarged family. There were two small portions partitioned by wooden screens, one on the ground floor and the other on the first, which served as living rooms. A staircase connected the two floors. I used to sit on one of its steps facing a tiny window and read my schoolbooks. The house was not witness to any major family events in the years we lived in it. The only bizarre incident I remember about the house is how a crafty ‘guru’ managed to convince my pious mother about his spiritual attainments, and spent a few days living with us performing elaborate rituals promising good luck to the family.

The guru was an attractive personality. He looked quite spectacular in his flowing saffron robes. When he propounded some philosophical truth in his deep voice, the ladies would melt and sigh. One day, while the pujas continued, it was discovered that a gold ornament with which the deity had been bedecked, was missing. This resulted in much commotion with the guru assuring everyone that he would get it back using his occult powers. While my mother and others were more than convinced with his assurance, somehow, some of us suspected foul play. The following day, when the guru was busy with the rituals, I went upstairs to the living room, where the guru used to sleep and conducted a quiet search of his personal effects. Lo and behold! I found the ornament.

After the puja and the elaborate lunch that followed, I quietly shared the news of my discovery with my mother. I don't know what she did thereafter\; the old fox had stealthily bolted away by the time we returned home in the evening. Not many knew what had happened. My father, generally given to loud outbursts in situations such as this, had not uttered a word. My mother was not in the least fazed by the incident. To curious queries, she had an evasive answer: “Who knows what happens in the minds of gurus.” Thereafter, all was quiet and life went on as usual. Looking back now, I admire the way my mother, a great diplomat, handled the case.

When my father retired from service, my brother Satyan and I persuaded the parents to shift to a bigger house, which we had found in Saraswatipuram, the new extension that was coming up in the city. The monthly rent for the house was fifty rupees. It belonged to a doctor who had a clinic in the city. The house stood just behind the Law courts. One had to cross a railway line at the back of the Courts to reach our home. This meter-gage railway line connected the city with Nanjangud, the temple town, better known for the famous tooth powder produced there by a well-known Ayurvedic Pandit. The Nanjangud tooth powder, pink in colour, tasted nice and was the thing used in almost all the households in the city including ours. Most of us remained stuck with the pink powder and didn't promote ourselves from the powder to the paste until we finished college and found jobs.

We had christened the train to Nanjangud as “Tooth Powder Express”. It was indeed a slow passenger shuttling between the city and the temple town, taking almost an hour and a half to cover a mere 15 miles. There was even time to jump on and off the train as it chugged along at a slow pace. There was a tiny station behind our house, the first halt for the train. We could hear the engine driver pull the little handle after letting out a smoky hoot and the train would start moving reluctantly towards its next halt, which was not far away. Life at home always echoed with the chugs and hoots of the Tooth Powder Express.

Though the new house was no sprawling colonial bungalow, it was exciting for all of us to start life in it, which was a little more spacious than the previous one, with a compound and a wicket gate facing the road. Since the building stood in the middle of a big plot of land, there was much vacant space around it for children to play. It was a simple box-like structure with small windows, a sit-out in front covered by a wooden lattice. In addition to a large hall, there were three small living rooms. From the hall, one could go to the kitchen, the god’s room and a fairly spacious bathroom. The toilet was located outside the house in the backyard, as was the custom in those days. There was also space in the backyard paved with granite to do the washing etc. There were two lofts\; one above the god’s room for storing things not needed everyday and the other in the bathroom to stack pieces of jungle wood used for heating the water in a huge copper container. Both the lofts always remained full to the brim. The house had no name, just a number: 2898. My brother Satyan named it as “Star Home” and hung a tiny nameplate on the wall in front\; but the name didn't click, perhaps because it sounded slightly unorthodox. Everyone started referring to the house as just “2898”.

After his retirement, my father spent most of his time at home. Though he had a benign and loose control on things and he never interfered with our activities, his continued presence at home made us feel that a mobile surveillance camera was keeping an eye on us. My sisters, four of them, had a better deal. Until they were married and left home, the parents, especially my mother, treated them like princesses. I must admit that at a later stage when the family enlarged further and the daughters-in-law arrived, some of the sisters were obliged to share the housework with them. My mother was keen that girls who came into the family shouldn't feel that they are treated differently from the daughters.

I guess that ours was the largest family living under one roof in the neighbourhood. We were used to incredulous exclamations about the size of our family from schoolmates and others but we prided ourselves on both our numbers and our closeness. My mother too did likewise but feared within herself that someone with an evil eye may inflict harm on the family. This is why perhaps in conversations with visitors she would cleverly ignore mentioning the exact number of children (fifteen at one stage) she was blessed with. I have even heard her mention a wrong number (say eight or nine), and quietly let loose a lie that the first two sons were those of my father's first wife.

But she was keen that the family should be well represented at weddings and other functions. To do this safely, she had devised a method of her own. She would go with three or four children, attend the wedding ceremony in the morning, and name a second batch to attend the reception in the evening. At no time I heard my mother lament on the unforeseen predicament of bringing up a large family.

Next to my mother, who largely spent her time sitting in the hall, directing activities and dealing with visitors, my grandmother was the most important elder in the family. We called her “ammamma”, meaning mother's mother. Since my mother was her only daughter, she had decided to stay with us after her husband died. Like most grandmas, she was a remarkable person.

The Kitchen was in fact my grandmother's territory. Getting the lunch ready was her portfolio. At dawn she would enter the kitchen, fresh from her bath, wearing a beige coloured sari (washed and dried by her the previous day) and anoint her forehead with gray stripes of vibhooti (sacred ash), light a lamp and drink a little water from a tumbler with a sprig of tulsi leaves in it.

She was a very meticulous cook. She would use only stone vessels called kachittis for preparing most of the dishes. Rice was cooked in a big brass vessel smeared with ash on the outer surface to enable easy cleaning of the black soot that would be deposited on it during cooking on an old-fashioned earthen oven using firewood. There was a stone pestle and mortar to grind fresh spices for curries. Her kitchen always tempted us with its enticing mixture of smells.

She observed all the traditional customs and regulations prescribed for a Brahmin widow. In the past, a widow was not allowed to remarry. She had to shave her head, wear a simple beige-coloured sari (specially woven for widows to wear using natural banana fibre), and cover the top of her head with the pallu of her sari. She was also to give up putting a bindi on her forehead. Basically, widows had to lead a very austere life with little joy. Mercifully, all these practices have gradually fallen by the wayside over the last hundred years.

I was very close to my grandmother. Her attire and the shaven head didn't appear odd to me. She looked like all other grandmas. She always made it a point to save for me a small portion of her evening palaharam, which was always some simple tiffin not made of rice. I used to wait for this tasty bite every evening. She slept at night on a simple mattress at one end of the hall. Before I went to sleep, it was my practice to lie down next to her for a while sharing her thin pillow. She would tell me little stories while she kept her fingers busy stroking my bushy hair to remove any sand or dirt that I may have acquired while playing in the open.

I must mention about a special assignment I had to do for my grandmother almost every month, about which she felt very embarrassed. A barber had to come home to tonsure her head. The job had to be done in the darkness before dawn, giving her enough time to have her bath and get ready before the house woke up. She would tell me in advance about the auspicious day on which this had to be done and definitely remind me the night before while she stroked my hair for sand before I went to sleep.

I would get up very early on that day, ahead of my father who was the first to wake up. I would open the door and quietly vanish into the darkness riding my father's bicycle towards the barber's home, some distance away\; and peddle back accompanied by the barber with his tool kit. I had devised this arrangement to make sure that the barber arrived on time without fail and completed the job. Over the years, the barber and I had become good friends and, as a result, this special job had almost become a routine. Apart from me, perhaps only a few had seen my grandmother sitting on a wooden plank facing the barber in the backyard next to the water tap. I suspect they deliberately avoided any discussion on it.

I was aware that my grandmother was deeply grateful to me for doing this delicate job without any murmur. This had certainly built a special chord of affection and love between the two of us. I am very clear in my mind that I was closer to her than to my mother and remained so till she breathed her last with her head on my lap at a ripe old age.

© T.S. Nagarajan 2008

Comments

Add new comment