Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Growing up in Princely Mysore

Category:

Tags:

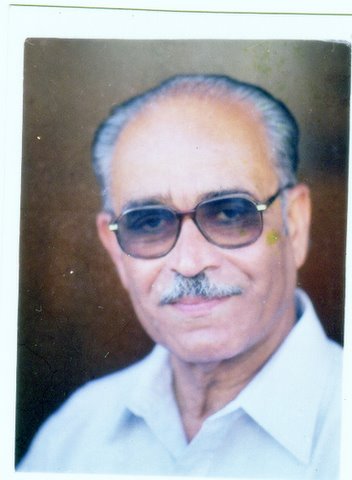

Bapu Satyanarayana, born 1932 in Bangalore, retired as Chief Engineer, Ministry of Surface Transport. At present, he is the presiding arbitrator of the Dispute Adjudication Board appointed by the National Highway Authority of India. He lives in Mysore, and enjoys writing for various newspapers and magazines on a variety of subjects, including political and civic issues.

T. Narasipur

In 1939, when I was around seven years old, my father was the manager of Mysore Silk Filatures, and posted at T. Narasipur, a small town in what was then the Princely State of Mysore. I was studying in a primary school.

T. Narasipur was a place where the rivers Cauvery and Kapila joined. It was considered as the Sangam (confluence) of three rivers including the legendary invisible Spatica Sarovara, just like the Triveni Sangam of three rivers Ganga, Yamuna and underground stream Saraswathi at Allahabad. At Allahabad, the Kumbh mela festival is observed once in 12 years, with lakhs of people taking a ceremonial bath on the auspicious day. No such ritual was observed at Sangam in T. Narasipur till recently. What I remember about two rivers is that while the Cauvery was sparkling, at the place where Kapila joined we could see a clear line of demarcation and, in comparison, the Kapila's waters were darkish.

My siblings and looked forward to the weekly Santhe (market) and seeing the wares spread out. Particularly, the jackfruit was a perennial attraction for us. We would wend through the men squatting and purchase kadlepuri.

Another attraction was attending plays staged by the Manjunatha Nataka Mandali to which my father used to herd us late in the night. Since my father was the big man for the place, he used to get the royal treatment, and we would all occupy front cushioned seats. The drama would start late in the night and end early morning.

We saw many plays, both historical and social. The abiding impression is Vasantha sena, Krishna Leela, Subhadra Parinaya. In Krishna Leela Gangadhrarayaru used to play that of Kamsa and in Subhadra Parinaya, Murarachar used to play the part of Subhadra so realistically that nobody would suspect it was male actor. I still recall the part played by Ramachandrachar in Vasatha Sena as vidhushaka and as Sudhama. Being a small place, Rama Mandira was the place visited by most of the people during evenings and my father used to take us regularly for the evening puja.

I remember that a cheery soul called Majid and his family lived in front of our house. During the mango season, he used to get lot of mangoes, and father used to buy it from him in bulk.

After the mangoes were fit for eating, my father used to gather all of us around him and the ritual of peeling the mango would start. He was an expert in peeling the skin in thin slivers with the knife in one continuous peel. After the full fruit was exposed with its glistening appearance making us salivate at the prospect of eating, he would show the skin like a magician dangling it like a speckled serpent holding it high from the end of the knife hanging down while in his left hand he held the juicy fruit. While we all sat transfixed watching his deft handiwork, he would cut the fruit into big pieces and would pop up major portion to his mouth and give each one of us a small piece! This would go on from one fruit after the other. At the end, we would all be given the clean-shaven goratu (seed/core) shaven clean to suck what was left of it!

Probably, this is the one weakness of his eating habit, apart from his fame as a Durvasa (Sage Durvasa appears in Mahabharata and known for his fiery temper) that has not left him. I should know it for I received terrible beatings from him. My mother and aunt were my protectors, interceding with him to spare me from further beatings. Even at his advanced age, I can see the flashes of his fiery temper. (Editor's note: An account of his father's life is presented at Ramanna, 105, "Not out".)

In those days, there was no electricity in T. Narasipur. Life was simple. On every Saturday evening, we used to join for bhajans, and I took a prominent part in singing them.

Something miraculous that happened is green in memory. I was around 10 year old, while my younger brother was 7 years. He was lying sick with typhoid on a bed on the floor of a room. There was no luxury of a cot for lower middle class people like us. The room had very high ceiling of Mangalore tiles. It was an extremely stormy night, raining cats and dogs with thunder and lightning. I do not know what possessed me. On an impulse, I just lifted the frail body of my brother in both hands, took him to an adjacent room, and placed him on the bed. Next moment tiles from the high ceiling just fell on the bed in the other room! After some time, I again lifted my brother, and put him in the drawing room. Believe it or not, the tiles fell on the bed in the second room also. My brother was safe. I can only say it is providence that helped. Or call it a miracle if you will.

Mysore

In those days, Mysore city was a glorious place. It was the seat of the government ruled by Maharajas who were responsive to the needs of the people living in the Princely State of Mysore. Mysore city was a place of grand parks, wide avenues with well-maintained drainage ditches built of stone masonry, tree lined boulevard and generally full of greenery.

Mysore was famous for and identified with jasmine, Mysore betel leaves (paan),Nanjangud Rasabale (plantain from Nanjagud) and delectable brinjal. People of my generation bemoan the fact they have practically disappeared. With better-off women cutting their hair short, it is now only the poorer housemaids who still keep the heritage by adorning their hair with jasmine. Like jasmine in women's hair, Mysore betel leaves too are becoming rare. Most of the area in which they were grown has been sold for profit, and is now being used for other purposes. The rice cooked with brinjals was a connoisseur's delight.

Mysore was full of greenery. The weather was indeed very pleasant - not too hot, not too cold, just salubrious. Probably that is the reason that people were very easy going, bordering on being lazy. My father used to call it a Lotus Eater's land. Unlike our other Southern neighbours, Kannadigas are often criticized for lacking initiative, being lazy and easily satisfied. Even now, the situation does not appear to have changed.

The Maharaja

The most enjoyable time for children was during the nine-day Dasara festival in the month of October. The Maharaja would ascend the royal elephant through a platform erected near the portico of the internationally famous Mysore palace. This ceremony was done following an age-old practice of reciting mantras specific to this event. After sitting under an ornate Howdah on the richly caparisoned royal elephant (Ambari aane in Kannada), the Maharaja would slowly wend through a ceremonial route to a place to worship the Banni tree. That tree was considered sacred because it was believed to be the tree on which the Pandavas hung their armours during their 12 months incognito exile, following the14 years they spend in the forest.

The most enjoyable time for children was during the nine-day Dasara festival in the month of October. The Maharaja would ascend the royal elephant through a platform erected near the portico of the internationally famous Mysore palace. This ceremony was done following an age-old practice of reciting mantras specific to this event. After sitting under an ornate Howdah on the richly caparisoned royal elephant (Ambari aane in Kannada), the Maharaja would slowly wend through a ceremonial route to a place to worship the Banni tree. That tree was considered sacred because it was believed to be the tree on which the Pandavas hung their armours during their 12 months incognito exile, following the14 years they spend in the forest.

My father would take us to find some place along the route to have a grandstand view of the procession. As I remember it, invariably it used to rain on that day. The procession was preceded and followed by military personnel in various groups colourfully attired, spruced up and wearing polished uniforms for the grand occasion. The members of the royal entourage would follow, including high officials and those who were recognized by awarding various royal patronage or titles by the Maharaja. They wore regulatory white pants, a black long coat, and a turban known as the Mysore Peta. The uniform was completed by a sash with rich border of woven gold thread slung across their shoulders.

The entourage would also include elephants, horses and camels, and they would march at appointed places. And there was the royal, band playing all the time both English and Indian songs. Frequently the procession would stop to receive the garlands handed over through a long pole with small platform attached reaching up to Maharaja. For children what was most entertaining was to see the tallest and the shortest persons marching, and also the sight of those carrying a basket to gather the droppings of the animals marching in the procession.

In those days on the birthday of the Maharaja, the whole city would march to the palace enclosure where the elders would be given one-rupee silver coin, while the children would get quarter of a rupee silver coin besides a packet of sweets. Even during the reign of Jayachamaraja Wodeyar, the father of the present titular head Sreekanta Datta Wodeyar, sweets were distributed in all schools on the Maharaja's birthday.

Tongas, bicycles and buses

Mysore city was a compact place, and often people could simply walk to their destination. The better-off people owned bicycles. City buses, two and three wheelers, and cars came later. The most common mode of public transport used to be the horse-drawn Tonga or Shapasand (Jutka gaadi in Kannada). There were two types of tongas. One had an open rectangular shape with extended roof on both sides, and the other one had an arched roof. The latter shape was conceived by Sir M. Visvesvaraya, a legendary engineer-statesman who was the Dewan of Mysore. This tonga was especially to serve as a mode of transport for Muslim girls going to school. The tonga had a curtain that could be stretched to cover both sides of the opening to serve as a veil to cover the young girls. This type of tonga has now disappeared.

The majority of the tongas were owned by Muslims, whom we called Sabis in Kannada. They spoke a version of Hindi specific to Mysore, which would have sounded strange to purists from north India. The tongawallas also spoke their own version of Kannada, but the local people were used to it. Recalling it now brings a wistful smile and sounds delectable to old-timers because it reminds us of the bygone era!

When passengers arrived in Mysore city at the railway station or bus stand, the whole place was full of tongawallas vying with each other for business. They would announce in Kannada ‘Namduke olle kudre eithe.' (My horse is good and will take you in good time to your place). When we arrived at the railway station, we would try to look for a well-built horse while another tongawallas, not to be outdone, would try to attract us boasting that though his horse may look small, it is faster than the others are. Finally, we would settle on the cheaper tongawallas, saving an anna or two (there were 16 annas in a rupee). Oh, this bargaining was so much of fun for children like us.

Piling into the tonga was also a ritual. While youngsters would sit in the front, next to the horse, the parents would sit at the back like a royal couple. Invariably the tongawallas would stand with his whip in his hand, which he would use with flourish to goad the horse to move. The whip would make a sharp sound when he swished the lash like a thin coiled snake unwinding in the air holding the rein with the other hand with words of endearment to the horse to trot faster and simultaneously making a clucking sound. He would usually stand with one leg firmly placed inside of the front trough and another on the metal step on the side.

Throughout the journey, the tongawallas would direct us to move either forward or backward to create a balance so that the horse did not get strained. Sometimes he would hand over the whip to us and we also tried to move it over the back of the horse. The other fun we used to experience was that when the horse moved with a trot it would raise its hairy tail and we would get thrilled in holding it in our hands. Of course, sometimes it would drop its dung on the road and even fart!

In those days, the whole road was open for cyclists. We owned a bicycle, and my father used it till the 1960s. At that time, there were only two brand names available. One was BSA and another was Coventry Rudge Whitworth, which was with us. For many of the present generation it would tickle them to no end if I say that in those days we had to have a licence for a bicycle. The licence fee was 8 annas (half a rupee) in the beginning per year. (There was also a licence fee of Rs. 15 per year for each radio.) The bicycle licence consisted of a round metal piece with a number punched on it. The licence had a central hole so that you could fix it to the front mudguard of the cycle with a bolt and nut. Nobody would dare ride a cycle without a license.

Each bicycle was required to have a light at night. The most common system was a simple dynamo (see picture) in the shape of a small barrel of about 4 inches, ending with a gradually reduced neck ending with a serrated movable ring at the top. While riding during the night, the cyclist would swivel the device so that the serrated ring became flush with the cycle tyre. When the cycle moved, the tyre would turn the dynamo's ring, and thus generate electricity.

Each bicycle was required to have a light at night. The most common system was a simple dynamo (see picture) in the shape of a small barrel of about 4 inches, ending with a gradually reduced neck ending with a serrated movable ring at the top. While riding during the night, the cyclist would swivel the device so that the serrated ring became flush with the cycle tyre. When the cycle moved, the tyre would turn the dynamo's ring, and thus generate electricity.

A wire connected the dynamo to an electric bulb in the front of the bicycle. The bulb was housed in a holder, and protected with a glass cover like in a torch and fixed at the top of the handle. The arrangement seemed so elegant. The faster the bicycle went, the more the electricity generated, and the brighter the bulb would burn.

In those days, we had a mortal fear of being caught without a light by policeman, who had an uncanny knack of springing suddenly from nowhere. The policeman's shout would freeze you to stop, and then he would emerge with a baton in his hand, wearing a khaki half pant. The half pant was a part of the police uniform. It looked very funny because it was so wide that the policeman's legs seem to emerge as thin sticks like a scarecrow. The uniform was the butt end of many jokes.

The other part of the uniform was the khaki turban, called Peta in Kannada. While the policemen wore black boots, the socks were made of khaki strips wound round the leg in successive layers. I guess there was no concept of stitching uniform to fit the person but it appeared everybody wore the same size, as it was mass-produced! (It was only around 1977 during the tenure of Devaraja Urs as Chief Minister of Karnataka that that the half pants were replaced by pants, and the turban was replaced by a smart cap.)

Any cyclist caught by the police without light at night was in big trouble! Fortunately, for the police any light would do - it did not have to be a dynamo and bulb system. Even a candle would do. So, often, some people just held a lighted candle. Others, who were more careful, would stick the candle into sand poured into a paper bag of conical shape, so that the candle light would be protected. It was quite a task to balance the candle and steer the bicycle at the same time.

For us youngsters, it was amusing to see the way the elders would get on bicycles. They would push their cycle until it had gathered sufficient speed, and then they would just hop on it while it was still moving. They wore either a pant or a tight fitting dhoti (Kacche panche in Kannada). They would gather the garment at the bottom near the ankle, and snap a clip around it, so that the garment would not come in contact with cycle chain or get spoilt by the black grease covering the chain. Of course, for them, getting down was also something of a heroic act. Many a time, somebody nearby would be asked to hold and slow down the cycle so that the rider could dismount safely.

A biography of an eminent officer of those days records a funny episode connected with cycling. He always went to his office by cycle. Since he was an officer, a peon was detailed to await his arrival so that he would be ready to hold the cycle and help the officer dismount. One day when the officer arrived at the office, for some reason the peon was not available. The poor officer went on going round and round on his cycle till the peon came because he was not able to get down by himself! Some onlookers had lined up to see this spectacle.

In the early 1940s, the buses in our area ran on steam power, and not on petrol or diesel. The steam was generated from coal burnt on the bus. The 30 km journey from Mysore to T. Narasipur, where my father used to work, used to take a long time with several stops. After the bus had covered some distance, the steam pressure would reduce, and the bus would stop. Therefore, it required topping up with more coal at the bottom of a long vertical chute like a chimney and firing it by blowing air to generate more heat and increase steam power. The chute/flume was attached at the back of the bus and underneath there was space just like in the railway engine, which ran on steam, power earlier. While the conductor would busy himself by cranking the handle of a contraption to blow the air forcefully, the passengers alighted from the bus and crowd around him to watch the process. It was a welcome break.

Pathans and Chinese

In those days, Pathans were a familiar sight on the streets of Mysore. Their colourful dress consisted of a loose pyjama with lot of vertical folds with narrow bottom, a full-sleeved shirt, a half sleeved open jacket with a turban, such as that shown in the movie Kabuliwala. They would wear their typical footwear, and often used to carry a short stick twirling in their hands. These Pathans with their fair colour skin, tall, well built and handsome - they made a formidable appearance. In comparison, we were small in stature, and they must have induced a sense of awe in us. In fact, if we wanted to silence a crying child, we would say that a Pathan would come and take him away unless he stopped crying. That would silence the child. In reality, the Pathans were an endearing lot. They spoke stilted Kannada, and though it amused us, we were accustomed to their ways.

They served a useful purpose in our society as moneylenders. People used to borrow money from them, with the clear understanding that the loan would be returned on a particular day. It was only a word of mouth agreement. The Pathan would promptly come on the appointed day and collect the money with interest. Anybody failing to pay would be taking a great risk.

In addition, the Pathan men used to sell hing and dry fruits - mainly figs, dates and Sakkar Badami (sweet almonds), for which Afghanistan was famous. The Pathan women, whom we used to call Arabi women, used to come carrying their wares in a basket. They used to sell beads, colourful tapes, bangles, tassel, etc. The women were also well built, and wore colourful clothes. If anybody called them home to check out their wares, the women would virtually force the potential buyer to buy something. They would not take ‘no' for an answer. Their sheer size and fierce ways would carry the day. In fact, the Pathan women had an unsavoury reputation, probably unfair, that they would kidnap children. Hence, some people used to close their home's door if they saw Pathan women in the neighbourhood.

The Chinese would come on the street, selling silk and other cloth, including toys. Their short, diminutive bodies would be slightly bent with the load of these materials, which they carried on their backs. They would hawk their wares in a peculiar singsong squeaky voice. They were a pretty picture and a sharp contrast to the Pathans.

The things we used

In those days, women would use only combs made of ivory\; plastic combs came later. The ivory combs would be around 4 inches long and rectangular in shape. They would fit into the palm, and would be cupped by four fingers to have a firm grip on the comb. The distinctive feature was that both the longish sides would consist of finely cut teeth. If the teeth got broken, the comb would be repaired by cutting new teeth by persons coming to the house carrying a small metal box containing their instruments.

We did not have stainless steel utensils in those days. Our cooking utensils were made of brass or bronze\; aluminium vessels were mainly used by poor people. All our cooking and heating would be done using these vessels. The heat came from a charcoal fire. The stove was a metal frame about 9"x9"x 9" with a grill at mid height The stacked coal would be lit either by pouring kerosene or fired from below using small wooden strips.

It was also common to use vessels made of soapstone (steatite). Soapstone is soft, easy to carve, and extensively used to make toys. Cooking vessels were carved out by scooping material from a block of soapstone. They were circular in shape and gradually reduced towards the top with triangular extension at the top to handle it. They were special because they used to retain heat for a long time.

The brass vessels used for cooking would be polished with a coat of tin. Brass utensils used for cooking would get covered with a layer of green deposit (verdigris), which is injurious to health. To prevent this, the inside of the vessels was tinned. This coat would wear out in time, and would have to be renewed. This renewal tinning (called kalaayi in Kannada) was an art. It was done by persons who would go to people's homes, asking whether they wanted their vessels to be tinned. This business was the exclusive preserve of Muslims.

For children watching tinning was an extremely riveting experience. This is how they used to go about it. The tinner would dig up and scoop out the soil in the shape of a bowl in front of the house. Then he would carefully arrange small splits of wood, over which he would carefully stack charcoal that he carried in his bag. He would have buried the short pipe projecting from the bellow near to the wooden splits. This bellow was a simple affair made of heavy leather. The pumping of the bellows would provide oxygen to the fire when it was lit.

Then, he would light the wooden scantlings. Slowly, the charcoal would begin to burn. Now the bellow was used to blow air, so that the charcoal burnt brightly, and strong heat was generated. Then he would place the vessel to be polished on the fire, and rotate it with a pair of tongs so that it gets heated all round uniformly. All the while, he would use the bellows with the other hand.

When he thought the vessel has become sufficiently hot, he would take a piece of tin, and press it quickly against the inside of the vessel. The heat would melt the tin. The tinner would take a rag, and with rapid movement of his hand, he would spread it thinly and uniformly all over the inside the vessel. When he was satisfied that it had covered all parts uniformly, with a flourish, he would dip the hot utensil in a bucket of water to cool it. This process would continue till he had polished all the vessels. It was fascinating to see how dexterously he would do this.

Diseases and medical services

Looking back, it seems so amazing what transformation has taken place. It appears even the type of diseases now have multiplied, and replaced the simple medical problems we faced in our youth. Except when plague set in, at which times we had evacuate our homes and live in tents, the diseases from which we suffered were very elementary, like sore throat, fever, malaria, cough and cold, indigestion, ear ache, typhoid, etc.

Allopathic medicines were not advanced in those days. True, there must have been many types of diseases which were unknown, or there was no remedy for them. Hence, people would die young, and life expectancy was low, unlike now. In fact, sixty-year-old men would be considered as venerable old men. Today, people live hale and hearty even into their eighties, though pollution, adulteration, poor eating habits, stressful life heart problem, and diabetes are taking a horrendous toll, despite the increase in longevity.

I remember we had a government pharmacy, which still exists. (Editor's note: Another account of medical services in Mysore at that time is Medical Services (?) in Princely Mysore by M P V Shenoi) At that time, the pharmacy consisted of a doctor sitting behind a chair, and a compounder, who would give the prescribed medicines to the patients. Near the doctor, there would be a basin of water mixed with potassium permanganate on a raised stool, and a towel. There were big bottles filled with assorted coloured - blue, green, pink, white etc. - liquids (medicine) arranged in a row, behind which the compounder would station himself. Corresponding to prescription written by the doctor, the compounder would pour the coloured liquids into the bottles the patient had brought. The compounder would paste a paper strip on the bottles, with triangular projections cut out to indicate the dosage! In case malaria was suspected, he would give out anti-malaria pills.

For the doctor, the stethoscope was the ultimate instrument of diagnosis. If anybody complained of sore throat, the doctor would ask the patient to open his or her mouth, and quickly swab it with what was called Mandel's pigment (throat paint). If the patient had a cut or a wound, the doctor would swab it with tincture of iodine. If the patient had an earache, the doctor would hydrogen peroxide to clean the ear. It seems so simple compared to today!

It is amazing what first aid cure we children used when we hurt ourselves while playing in the field. It is probably unbelievable today that we would take the field soil into our palms, carefully remove bigger particles, and blow out the leafy part. This would leave a nearly dusty residue, which we would mix it with our saliva and apply to the wound! Wonder of wonders, it would cure us practically in all cases.

Of course, we cannot think of such a remedy nowadays. Now, when a child gets hurt, we would immediately clean the wound with clean cotton dipped in Dettol, or apply any antiseptic powder, or a lotion and bandage it, or close it with a band-aid.

May be that is progress. Children then never bothered about such minor injuries and continued playing but now the children have been trained to run to their houses to attend to such wounds immediately so that the wound may not become septic.

In case there was an indication of pus formation in the wound, a poultice made of hot dough placed on a betel leaf would be placed against the affected portion, and tightly bandaged with a cloth. A day or two later, the bandage would be taken out. If the wound were found to be ‘ripe' with whitish pus appearing, the area around the wound would be squeezed to push the pus out. The patient would howl with pain, but that did not matter. (Editor's note: I remember a similar treatment for my younger brother in Jaipur in the mid-1960s.) Once all the pus was out, the wound would be cleaned, and it would be covered to let it heal naturally over time.

Sauna bath - Old Mysore style

On Sundays, we children used to go through a ritual oil bath, given by our mother. We would enter the bathroom wearing a loincloth (Kaupina in Kannada) and apply castor oil all over the body, including the head and tapping it thoroughly so that it gets into pores. Sometimes, my mother would apply the oil and massage it thoroughly. We had to soak in it for some time so that it gets into all the pores in the body.

On that day, the big cauldron (Hande in Kannada) of water would be heated to almost boiling temperature so that there would be enough hot water for everybody. Then, she would forcefully throw water against our body with a brass vessel (plastic mugs were unknown at that time). It was such fun and we used to enjoy it.

After some time, the whole body would be rubbed thoroughly with wet soap-nut powder (shikakai in Kannada) till all the oil would be removed from the body. Then, clean hot water would be poured all over the body\; the use of soap was optional. Then she would dry us with a fresh towel. Oh, how fresh we all felt!

Of course, due to use of hot water, we would sweat profusely and had to dry ourselves repeatedly. I found it to be a delectable experience. There would be a bed made up waiting for me. I would just dive into it straightaway from the bathroom and cover myself with a kambal (a rough black blanket) from head to foot. After some time, due to the effect of hot water bath, I would be sweating profusely from all the pores of the body. The whole cloth covering me would become wet. Then I would emerge, and thoroughly dry myself by vigorous towelling and the whole body would feel light. There would be a welcome cup of coffee waiting for me. Sipping it would be my sense of supreme enjoyment.

It is a sort of equivalent of present day sauna bath but I can vouchsafe that it was far superior in every respect.

Health drink - Castor oil

If Sunday bath was a thoroughly enjoyable experience, there was another ritual that we all hated. But, we had to go through for the sake of keeping good health. Periodically we would be asked to drink castor oil. The idea was that it would purge the system. In case we were suspected to have round worms in our intestines, the castor oil would do the job of deworming also, for we would take a shining white powder (We used to call it santinine powder - I do not know the exact chemical name) the previous night. This powder would kill the worms and castor oil would help to purge them from the body.

In those days, castor oil was unrefined - it came straight from the mill. It was no doubt very pure but a little darkish in colour and quite thick. To make it easy for us to drink, coffee would be mixed in. Even then, it was thoroughly distasteful, if not a revolting experience. But, we children had no choice but to drink it, with elders standing around coaxing us to drink. We would manage it by closing our nose between thumb and fore finger, closing eyes, and gulping it in one go. We would keep a piece jaggery in our hands to swallow immediately afterwards to remove the vile taste in our mouths.

Vignettes of life in Mysore

We led a simple life. We had never heard of fans or other kitchen conveniences. Even a chair was a luxury. Cooling of water was done by filling a big earthen vessel and placing it on wet sand.

Our home had no cots. We slept on the floor. During the day, the beds would be rolled and stacked one above the other against the walls. When night came, the beds would be spread on a mat, touching each other. We all slept blissfully till father would wake us up in the morning with a familiar shloka (Ahlaya, Draupadi, Tara, Tara, Mandodari thatha, pancha kanyasmare nithyam maha papa vinashanam, which means "If you remember these five great and chaste women -who figure in our epics- in the morning, it would wipe out our sins.") As we got up we had to hold our hands with turned up palms facing us, and recite a Sanskrit shloka: karaagre vasathe lakshmi, kara madhye saraswathi karamule gouri prabhte karara darshanam (In the tips of fingers resides Goddess of wealth Laksmi, in the middle of the palm resides Goddess of learning Saraswathi, in the stem of fingers resides Goddess Gouri, the supreme mother of the universe and for viewing these Gods there is no necessity of going to any temple). Then we have to reverentially press our eyes with the palms of our hands.

Or, he would peremptorily upbraid us, saying, "Get up you lazy fellows, the sun is up in the sky and it is already morning." If children were fast asleep, water would be sprinkled on their faces. Once awake, the children would busy themselves with the day's work, helping in the household chores.

All guests would be welcome at any time of the day. Visitors would drop in at any time of the day unannounced. It was customary to serve them coffee. Well-roasted coffee seeds would be always available in the house. We would grind the seeds into coffee powder by a hand-cranked machine fixed to one of the wooden planks in an open multi-tiered cupboard. At that time, there was no question of adding chicory to the coffee. After pouring hot water over the coffee powder in a vessel, we would strain it by filtering the coffee with a thick cloth and the coffee decoction would be ready in no time. It would taste heavenly. Then cloth would be washed. Due to repeated use, it would acquire the colour of coffee.

If the visitors included girls, it was normal to ask them to sing. It was taken for granted that the girls knew how to sing. When the girls grew up to their marriageable age, their ability to sing would be one of the attributes prospective grooms and their families would look for. So, girls were encouraged to pick up singing from a very young age.

During those days most of us went barefoot as footwear was costly. Shoes or sandals were a rarity because they were costly. Mostly, we walked barefoot. Even to our schools/college we walked barefoot, wearing only pyjama and shirt.

The girls would wear long flowing skirts reaching to their feet. Unlike today, no girls had a bob-cut hairstyle - all of them had long, plaited hair topped with bunch of jasmine flowers. In fact, it was a fashion for parents to exhibit their children adorned by covering the head and plaited portion full of closely strung jasmine buds using either a thread or even thinly peeled thread like strips from the stalk of banana plant. Peeling would be an art for it had to be soaked in water so that it would make a strong thread to string the buds. Girls thus bedecked would be sent to houses of neighbours to exhibit their jasmine covered head adorned with other ornaments.

Ironed clothes were a luxury and the best we children could manage was to fold the clothes carefully and keep them either under a heavy object, or our pillows during the nights.

Since money was scarce, my father would purchase a long length of cloth of one colour for stitching everyone's clothes. Everyone in the family would wear clothes made from the same material, like a uniform.

It was common for the boys to inherit their older brother's or uncle's clothes. There was no question of protest. For girls and women, there was no concept of making an effort to match the colour of the blouse to the sari - they just wore whatever available. The exception was that they wore colourful silk and embroidered skirts during Hindu religious festivals.

For children living in Mysore, three sights connected with royalty were perennial attractions. The Maharaja had a garage full of costly cars like Rolls-Royce, Mercedes-Benz, and Bentley, and a stable with pedigree horses. Frequent visits to these two were a must. Another attraction was the place where elephants were kept (Ane karoti in Kannada). It was enjoyable e to see the elephants.

There was a boy called Mysore Sabu who used to playing with the elephants. Sabu was well built, with an impressive shining torso. It was fun watching him play with elephants In fact a famous Hollywood producer who came to visit Mysore was so captivated that he took Sabu to America. A riveting account of his life has been written by the famous photo- journalist T.S. Satyan in his book, Alive and clicking. (See a video about Sabu here.)

An elephant with a Mahout on top was a common sight on the streets of Mysore. At that time at various houses, people would be ready with coconut and lumps of jaggery to feed the elephants. In case the elephant dropped the dung while walking, children would rush to place their feet on the warm dung for it was believed elephant dung had medicinal properties!

I have many more stories about Mysore. But, let me close with two quaint remembrances that bring a wistful smile to me when I look at how we have changed.

Having a clock or a watch was a great luxury in those days. Few families had them, and no one knew what the exact time was. Probably that is why the government would switch off electricity supply for a split second at 9 pm. This would serve as a signal to those who had electricity in their houses to begin closing down for the night, which included sending children to bed.

Though electricity was available in homes, there were no electric streetlights. The streets did have poles for lighting. Instead of an electric bulb, a street lighting pole had a glass dome, with provision for a wick and oil. In the evenings, as it became dark, a man would come with a long pole that had a lit wick at its end. He would use the lit wick in the hand-held pole to light the wick in the street pole.

© Bapu Satyanarayana 20012

Comments

Add new comment