A Child’s Horrifying Memories of India’s Partition

Category:

Bimla Goulatia got her doctor’s degree (MBBS) from

Editor's note: A related story written by her oldest brother, Pran Bhatla is available here. Mr. M. P. V. Shenoi has faciliated the writing and publication of this story.

In the 1940s, my parents were living at House No.7, Galli (Street) No.7, Guru Nanak Pura Lyallpur (now Faisalabad), which is now in Pakistan. I was five years old. I had two older brothers, who were 13 and 7 years old, and a younger sister, who was 2.5 years old.

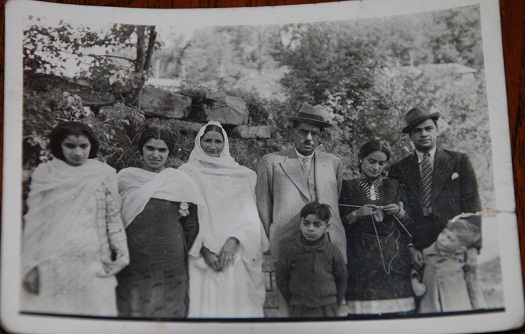

My father, H.R. Bhatla, was a Professor of Physics at Government College, Lyallpur. My grandfather, Rai Sahib Bishan Das Bhatla, had retired in 1938 as a Garrison Engineer, a high rank and status held by only a few Indians in those days. After he retired, the Government re-employed him because World War II had started, and it increased the need for experienced engineers. As a result, he continued working till he died in 1943.

We were a happy and prosperous family. We owned a Kothi (big house) in Meghiana, a house in Rawalpindi, and a villa in the hill station Murree. We always enjoyed our summer holidays at Rawalpindi, Murree and Meghiana.

The summer of 1947 was totally different. That summer, one day I saw my father milking our buffalo, a job that was normally done by our milkman. I asked my mother, “Why is Papaji milking the buffalo?” She replied that the milkman would not be able to come to our home because there was a curfew, which meant that people could not leave their home. The same curfew hit us, as we children were not allowed to move out of the house to play.

One day we children were told that our father gone to Meghiana, where my grandmother and bhua (father's sister) lived. In his absence, a family friend was staying with us. We used to sleep on the rooftop, which was cooler than the inside of the house on the hot summer season. Whenever there was some commotion in the street, our friend would get up, take out his knife, and tell my mother, "Sister, they are coming." We could not understand what he was talking about, and used to laugh at him.

On the day the curfew was relaxed, we were taken to Meghiana by a relative sent by my father. One day, at lunchtime, I vividly remember the servant was making rotis on the tandoor, and the dhobi (washer man) had come to take clothes to be washed. Life was normal.

Suddenly, everything came to a halt. We had to leave our house in a hurry. I picked up my dolls to take with me. We were all taken to a bank for safety. The bank manager was a distant relative. The bank also had police protection.

That was the last time we saw our Kothi in Meghiana. Once, my father did go back from the bank to the Kothi to pick up some things including my grandfather's double-barrel gun. On his return, he told us that many things were missing from the house.

The stay at the bank was horrible. There were three families - ours, the bank manager's and my dad's uncle, who would shout all the time in pain because of urine retention. The elders were concerned about the fate of the women and children in case of an attack, mob managed to get into the bank, overpower tem and take women. So, the elders had made a pact that in case of an attack on the bank, they would kill the children and women themselves before fighting the attackers. Two or three times, there was fear of a successful attack. We children had decided that instead of using boiling hot water to make tea, we would throw the hot water on the attackers. Each time, the women and children were herded into a small room, but the attackers were not successful. At nights, there were disturbances and shouting, and we could see fires that had been lit by mobs.

The bank manager was a clever man. He told the police that we would be willing to give them lots of money if they would take us safely to a camp from where we could go to India. My father gave them gold coins. At last, the police asked us to get ready for the camp, take only three clothes each.

The police searched every one before we got onto the police van. They even broke my dolls to check whether we had hidden any money or gold inside them. So much so, they even broke the rotis we were carrying - just in case we had hidden anything in them.

My mother did not want to give up her earrings. She begged the police to let her keep them. So my father gave them more money, and they allowed us to keep the earrings and wedding rings. My mother gave her valuable clothes to the bank manager, in the hope of getting them later in India, but she never got them.

On our way to the camp, after a short while, the police halted us. There were people with weapons running in the street in front. Some were playing cards on the roadside. My father was very disturbed because his young unmarried sister was with us. He pleaded with the police for protection, and promised to give them more money. Better sense prevailed, and the police took us back to the bank.

After few days, we were again taken in the van, and this time we made it to the camp. For me, the sight at the camp is unforgettable, even till now. Every body looked dirty and hungry, running here and there in search of food, shelter or loved ones. We slept on the floor. My younger sister made a lot of ruckus and wanted to go back to her home. My mother pacified her with great difficulty.

A day came when we were asked to walk down to the railway station carrying what little possessions we had. I had my broken dolls - the reason I still have fascination for dolls. We had to come back to the camp for there was not enough Sikh military with the train for safe passage.

Ultimately, one day we boarded the train to India. It was the height of summer. But we were not allowed to open the windows or doors of the train. There was no water to drink so people gave their urine and sweat to the children to drink. We all had sore eyes because of conjunctivitis.

The train stopped near Lahore for a while, and every one came out to have fresh air. People were sitting on the railway lines and on the roof of the train. There was a sudden noise and my mother was hit on her head by some utensil falling from the train top. We were shocked to see her head bleeding. My father crossed over the railway tracks to get some help for her.

After many hitches, our journey ended at Attari, a border town in India. Here we got boiled black channa to eat. That was the most delicious food I ever ate!

Soon, we reached Jalandhar, where we entered a house that belonged to a potter. It was full of earthen pots. Then, my father went to Prof S.N. Sehgal, his friend, who offered us food. The dal was tempered with ghee. It was heavenly! Then we moved to Hoshiarpur, where my father was posted at the University College as a Professor of Physics. The house allotted to us was not vacant, so we stayed with Prof. H.R. Gupta, who taught Mathematics. He kindly gave us a barsati (a small room on roof) and kitchen. That summer, the rain gods showed their anger with torrents of rain, lightning, and hailstorms.

We had very few clothes. My father went out and bought two thans (rolls) of blue check cloth and a yellow cloth with lines. All the family members got their clothes stitched from the same material!

We shifted to our own house and started life afresh. My father was missing for few days. On his return, he had quite a bit of baggage with him. We were surprised and shocked to learn that he had gone to

Every time I think back on those days, I always wonder how my Dad never thought about his own safety. Initially, he had gone from

During those days, I often used to ask my mother, “Who are these ‘Muslims’?” The same question was asked by a Pakistani girl about “Indians” when I visited

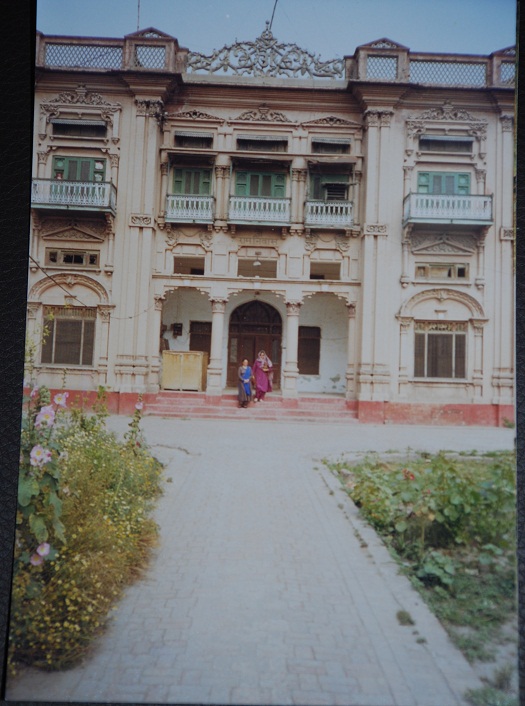

During my visit, I saw my

The bungalow in Murree had been demolished, and flats built in its place. I could not go to

© Bimla Goulatia 2012

Comments

Add new comment