My Memories of Three Princely States

Category:

Tags:

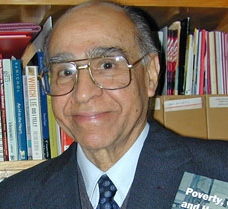

A.H. Somjee received his Ph.D. in Political Science from the London School of Economics. He is a charter member of the Simon Fraser University, Canada, where he is also an Emeritus Professor of Political Science. He has taught at the University of Baroda, the London School of Economics, University of Durham, and the National University of Singapore. He was also appointed as an Associate Fellow at the Queen Elizabeth House, Oxford University, and was invited to Harvard University, several times, as a Visiting Scholar.

India’s Princely States are all but forgotten. But some of us still remember them for the simple reason that they did try to make life different for their inhabitants. I had the privilege to live in three different Princely States, all in the northwest of India.

They were the Holkar State of Indore, Udaipur State of Rajasthan, and Baroda State of Gujarat. My entire life in India was spent in these three states. I took my graduate education in the U.K., and migrated to Canada at a mature age of forty years.

More than eighty years ago, I was born and educated in Holkar State of Indore. Theoretically speaking, you had to be born and brought up in Holkar State to be admitted to Holkar College, which was prestigious in Indore. But to obtain a certificate of birth etc. was a swindle in Holkar State. I was not even eighteen before I got a certificate that I was a Holkar State resident. That helped me to be admitted to the then highly prestigious Holkar College.

My Holkar College years were quite formative and useful, and I felt honored to be a student there. The Indore Christian College, run by Canadian missionaries, was another prestigious college, where I went for my Master's degree.

I studied in Holkar College from 1942 to 1946. As students, we could discuss various political issues but avoided direct criticisms of the State rulers. We were relatively freer to denounce what was happening in British Indian provinces. We could not openly or directly discuss in courses on civics and politics the problems that India faced. We had to quote some thinkers instead and then laboriously go on defending the position of those thinkers or denounce them. In any case, our criticisms were not heard outside the campus.

While I was a Holkar College student, the Second World War was on, and we just did not know how long it would last. The cantonment city of Mhow was close to Indore. Mhow was full of soldiers. It was very common for us to see soldiers in groups coming to Indore for sightseeing and other kind of enjoyment. Most of us were advised to keep away from them. But some of the soldiers wanted to talk to citizens, and in particular to students.

The road from Mhow to Indore passed through Holkar College. And that meant that most of the soldiers, either in jeeps or in tongas, passed through our college. Their greetings with students, which were quite scary, were always not very welcome. Some of them walked part of the way from Mhow, and that meant they would come in contact with students going to college. Others wanted to know more about us, so we would get off our bicycle and talk to them. What I remember, even after nearly seventy years, was that we found it hard to understand their accents. What was clear was the final parting, when they said, "Thanks for your bloody kindness!"

The ruling Maharaja Holkar was quite a withdrawn person. No one in our college knew what he was like, although everyone wanted to have a word with him about one thing or another.

Nevertheless, the Maharaja could not totally ignore Holkar College, and he did come to play a cricket match. I used to be an extra in the Holkar College cricket team. A match was arranged between Maharaja's Eleven and the Holkar College team. The College players were told that they should not aggressively try to get the Maharaja Out. Even if the Maharaja happened to send catches came their way, they should try to make them look difficult and drop them. As it happened, in the match, after scoring six or seven runs, the Maharaja hit the ball into his wicket. The umpire had no choice but to declare him Out. The standard of cricket in the Maharaja's Eleven had some of the finest players who played provincial matches. They defeated our team, which was not a weak one, but not as good as the Maharaja's team.

I joined Indore Christian College in 1946. I was part of the first batch to study M.A. in Political Science at this college. Here, we were more critical of the British rule, and Maharaja's complicity in it. As the hour of India's independence drew nearer, we also felt freer to criticize whomever we wanted to criticize. As I remember, in two years of our M.A. course in Political Science, from 1946 to 1948, we were increasingly becoming bolder to take on any aspect of national policy, or even international policy, for closer examination and criticism whenever we felt necessary.

I immensely enjoyed those two years of my M.A. studies in Political Science under the guidance of Professor N.C. Chatterjee. Chatterjee was a brilliant teacher, who could allow us to take any position and then go on to defend it. At times, it appeared that he did not have any position of his own. He would contrive to be in opposition to whatever we wanted to say, and make us think and argue more and more. He thought, as a teacher, he should not have any position excepting one that was in direct opposition to our own. Some of my contemporaries used to get quite upset over it, but he did his work and made us think as much as we possibly could.

My Indore years ended after I got my M.A. degree. I tried very hard to get a job in the two colleges of Indore but did not succeed. Disappointed, I went to Udaipur, another princely city, not far from Indore. In Udaipur, I was appointed a lecturer in Political Science in the Maharana Bhupal College, which was named after Udaipur's ruler.

Udaipur was a smaller Princely State, but it was quite a prestigious place for its history, and the courage of its rulers. They had defied the great Mughal rulers of Agra, and had been given terms of honor by the Mughals.

Unlike Indore, in Udaipur, the people were respected the ruler and submitted to him. Every evening the ruler of Udaipur would go out for a drive, and his car would be followed by two busloads of staff. And whenever the car carrying the Maharaja passed on the road, people used to stop their tongas, or get off their cycles, and greet the king or just stand in silence. The people spoke very fondly of the Maharaja, and never used unbecoming language or words against him.

A year after Indian became independent, nobody was sure what would happen to the Princely States. The news we received was that Sardar Patel, India's Home Minister, would integrate them into the Union, and create new political entities by way of States of India. There were more than five hundred such States that had to be integrated, and he did succeed in integrating them, barring a few exceptions, into the Union of free India.

In my more than three years stay in Udaipur, the Maharana never turned up in College. And slowly, but surely, he was forgotten. After the partition of India, many families migrated from Pakistan by carts as well as on foot. They were given shelter in the camps, which were constructed for them on the outskirts of the city. And from there they spread into rest of northern India. These migrants did not have much respect for the royal family. Their first priority was to establish themselves economically and then move into the main body of the city.

The same was true of the rising middle class of Udaipur. They too, after their education in Udaipur, went either to Jaipur or to New Delhi. The young men who went to College, wanted leads and help in their careers, and for that, they used to stick to their teachers throughout their stay in college.

The students thought I was worth taking seriously. Consequently, they used to come to my classes or join their friends who were coming to see me in the evenings. At least twice to thrice a week, we used to meet at my residence and talk politics or India's development process. As time went on, their number increased. Since I was unmarried and alone at home, they had no hesitation in approaching me, and sitting down to ask questions or just listen to their professor.

My restlessness in Udaipur was known to them, and some of them felt that before long I would be gone. And after continuously telling me to consider what a wonderful place Udaipur was, they too gave up that kind of line to impress me. The Indian economy was moving very slowly and most young people, including myself, felt that there should be a way out for people who were above average, wanted fresh challenges to face, and grow in that process. That was true not only of Princely States of India but also of the rest of the country.

Professors Varma Saheb of my College, Bordia Saheb of Vidya Bhavan, and Saxena Saheb, the principal of our college, knew the reasons of my restlessness. They thought it was inevitable but it would pass, considering the fact that I was younger and much more exposed to outside influences. And they wanted me to settle down to work, which I was already doing, and they thought that would cure me. But my restlessness continued. Why were the things not moving fast enough, was the question I used to repeatedly ask. Was the princely background of Udaipur was responsible for it? And I could not get an answer for it. Sometimes, I used to hope that the Sindhi refugees, who passed through Udaipur district in big numbers, would do something to the place and increase the pace of change. But that did not happen.

In 1951, I left Udaipur to pursue my Ph. D. at the London School of Economics (LSE). Throughout my stay at LSE, I used to be in touch with Varma Saheb. In 1955, after I got my Ph.D., I returned to Udaipur. Varma Saheb and Prem Narain Mathur, Rajasthan's education minister at that time, tried very hard to retain me in Udaipur. But they could not find money to create a post for me. Therefore, in 1956, I left for Baroda (now Vadodara) to join Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, in another princely state of India.

Baroda University was quite a challenge for me. Baroda was another Princely State, quite different in its makeup and dynamics from Holkar State of Indore and Udaipur. Mrs. Hansa Mehta, the Vice-Chancellor of Baroda University, warmly welcomed me to the place. And I lived there for nine years. Baroda University was known for its educational developments, even though it was located in a Princely State, and was part of Bombay State after India's independence, until Gujarat became a State in 1960.

Baroda was a more or and less self-contained university. It did not consider itself inferior in any way to Bombay University or Delhi University. All around Baroda there was nothing but emphasis on growth and progress. It also had some of the great ideals of what a good university should be. The University administration was extremely good with the faculty and students. And they always believed that a university is nothing more than its faculty and students. Together they built a great University, and its faculty and students were very proud to be part of it.

The Maharaja of Baroda did not matter very much to the University. A Maratha by origin, ruling a part of Gujarat, he had a difficult job to do. As a Maratha, he should have been in Maharashtra, a neighboring province. But as the history of India evolved, he was in Gujarat. He and his father were aware of this, and tried to do as much for Baroda as possible. In that, his father excelled. He gave a very good administration to Baroda, tried to make education compulsory, and established a Baroda College, which later became Baroda University. Even in villages, he and his men tried to give a fair and progressive administration.

The older generation in Baroda remembered all this. But to younger generation all that was history. Once Gujarat became a state, Baroda became a junior partner after Ahmedabad, which was Gujarat's leading city and capital. This brought about major changes. Everything that Maharaja Sayajirao had done was forgotten.

My encounter with the Maharaja of Baroda happened in a club near the University. The club had invited the Maharaja to speak, and he readily agreed. Afterwards, with a plate in his hand, he roamed around to meet people. I was one of them. And we must have spoken for nearly an hour. He was very keen on knowing what I did at LSE, and how I liked Baroda. His assistants were all restless, and tried to draw his attention, but he and I went on talking. And that was the end of my encounter with the Maharaja.

I spent forty years of my life in three Princely States: Indore, Udaipur and Baroda. Barring my early years in Indore, I never felt that I could not express myself freely. The three Princely States had their own ways, but not for the general public or for university people. And as time passed, the people became bolder in their criticism of the administration that the princely rulers had provided. In return, no one from these Princely States tried to answer. They knew that their days were numbered, and there was no point in trying to justify their rule.

Over time, the differences between British Indian provinces and Principalities of Maharajas were forgotten. Very few people could tell the difference between British Indian provinces and Princely States of India. India had successfully integrated the two into one country.

© A H Somjee 2012

Comments

Add new comment