Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

My memories: Delhi 1946-1953

Category:

Tags:

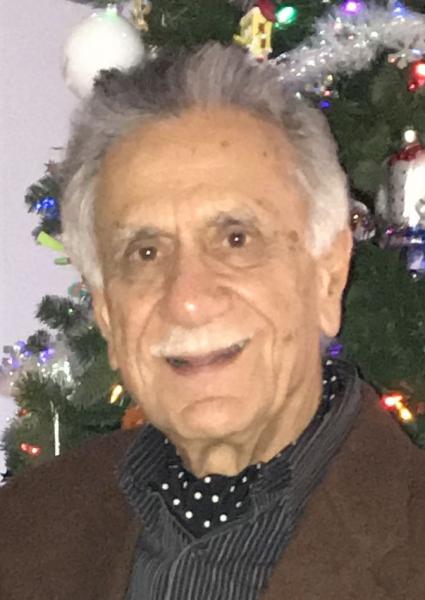

Mahen Das studied mechanical engineering at IIT BHU. He retired from Shell International, in 2002, after 43 years of work in their petroleum refineries and gas plants. He practiced as an independent consultant until 2009. His learning and experience has been acquired from hands-on work, at all levels of asset management, at 40 sites in 22 countries. This includes Process Management, Maintenance Management, Engineering Management and Optimisation of reliability, Integrity and availability of plants. Mahen is a co-author of Case Studies in Maintenance & Reliability. He plays golf and bridge.

Editor’s note: The author’s memories of Lahore 1937-1945 are available here. http://www.indiaofthepast.org/mahen-das/life-back-then/my-memories-lahore-1937-1945

Our home and daily life

In 1946 Papaji was transferred to his company, The Delhi Cloth and General Mills (DCM), headquarters, Delhi. We moved there in April of that year. We were given accommodation in the company officer’s housing compound at Rohtak Road, Karol Bagh.

My mamaji lived on Babar road, close to Bengali Market. During vacations, we would spend some days there. Two entrepreneurs Bhimsen and Nathu were starting mithai shops. Mamaji was a gourmet, and apparently had that reputation in the neighbourhood. So, Bhimsen and Nathu would come with their preparations and request Mamaji to sample them and give his opinion and suggestions to improve, which mamaji did. Today, both Bhimsen and Nathu are very successful restauranteurs in Bengali Market. Perhaps, some credit goes to my mamaji.

In our compound, there were 12 buildings in two rows, 6 in each row, each containing two apartments. The ground floor apartments had a lawn attached to them; the first-floor ones had another floor which served as a terrace.

We had a first-floor-with-terrace apartment, number 7. It had 6 rooms, two bathrooms/toilets, a kitchen, a store, and a veranda. There was a full terrace and a small room called barsati. The kitchen had a 30-inches wide stone platform, about waist high running along one wall. On this were two chullahs made of bricks and mud. At the end of the platform, there was a washing corner with a tap. We had kept our hammam (wood-fired water heater) also there. Along the opposite wall there were racks for keeping pots, pans and other utensils. Part of a rack could serve as an eating table for one, if needed.

The chullahs were fired with hard coke. Setting the coke afire was quite an exercise. One laid a layer of charcoal pieces on which the chunks of coke were piled up. The charcoal was lit with kindle wood or old newspaper. The set up was then left alone for 10 minutes or so. It used to generate a lot of smoke, for which the doors between the kitchen and the rest of the hose were shut tight. Once the coke got going, the smoke cleared and the chullah was ready for cooking. One load of coke with some replenishment, generally, lasted the whole meal period, breakfast/lunch or tea/dinner.

Instead of fixed chullahs, many households used angithis which could be picked up and moved around. Because of the heavy smoke during the 10 minutes of smouldering period, the angithis were moved outside the houses until the smoke reduced. This caused pollution of the atmosphere, especially during autumn and winter evenings, resulting in irritation of eyes and throat - much like what happens now due to other reasons.

A newer, cleaner, quicker and more efficient option was the pressurized kerosene stove. It was popular in Bombay and further south of the country; not so in the north. Because of being pressurized, it was more hazardous than the good old chullah; one heard about accidents caused by bursting stoves.

Cooking utensils consisted of various sized patilas (circular pots with a lip) and their dhakkans (covers) made of brass, and various sized karahis (wok), generallymade of iron or steel (not stainless). Daals (lentils) and curries with gravy were always cooked in a patila, while dry curries always in a karahi (like the Chinese wok). Karahi was also the vessel for deep-frying, e.g., pakoras or poories and making sweet delicacies e.g., sooji, moong or gajar halwa or rabari.

Atta, the dough for making roti/chapatti/phulka/paratha was kneaded in a paraat made of brass. The ball of dough was rolled flat on a flat round stone (generally marble) chakala with a wooden belana (rolling pin). This was cooked on a hot tawa, round, slightly concave plate of steel.

Food was served in a thali. Daal and curries with gravy were served in a katori/katora while dry curries and roti/chapatti/phulka/paratha directly on the thali.Generally, but not in every household, a chamcha (spoon) is laid out to facilitate eating the daal or curry gravy. A karchchi (big spoon) and a khurpi (flat spoon for scraping) were used for stirring/scraping while cooking.

All these implements, thali, katori/katora, chamcha, karchchi, khurpi were made of brass and needed periodic tinning (kalai). Some fancy, expensive katoras were made of kansi (bronze). Water or milk was had out of tinned brass tumblers. These were called glass, though not made of glass.

The cooking media were vanaspati ghee(hydrogenated vegetable oil) for most cooking, vegetable oil (mustard or coconut) for deep frying or some special vegetables e.g., methi aloo , and desi ghee (clarified butter), used sparingly for roti/chapatti/phulka/paratha, or tadka for daal. Pudeena (mint) Chutney (literally, “for licking”, a spicy, tangy condiment) and masala for cooking were crushed/ground in a dauri (a stone bowl) with danda (a hefty 3” round, 20” long wooden baton with rounded ends) in Punjabi households; on a sil (a flat stone slab with a rough surface) with a watta (a hand sized piece of stone) in Delhi/UP households.

Whole dry spices were crushed in a steel okhali (a sturdy 6” round, 8” deep cylindrical vessel) and a moosal (2”/1”, 10” long tapered steel baton). Thus, the saying, “jab okhali mein sir diya hai to moosal se kya dar” when you have dared to stick your head in the okhali, do not fear the moosal!

Bulk supplies were kept in the store room. Other than sacks of wheat, rice and sugar, tins of ghee and oil, containers of whole condiments, I remember martbaans or byaams full of pickles. Martbaan or byaam was a beautiful glazed porcelain vessel with a 3”-4” neck closed with a screw cap. For some reason, they were always off-white in colour with brown edges and brown caps. They were used only for storing achaar (pickles) and murabba (sweet/spicy preserve), made at home. Many seasonal vegetables were pickled, as were raw mangos. Small apples, aamalaa and carrots were used for murabba. For some reason, desi ghee always came in a roughly 12”x12”x18” sealed 18 seer tin called peepa. It had a 1½” round opening near one corner of the top face, closed with a round piece of tin-sheet soldered to it.

Tap water was good enough to drink (It was not until 1955 that pollution in the Jamuna caused a jaundice epidemic and people started to boil tap water before drinking). During summer, water was stored in unglazed terracotta pots called matka or ghada. Evaporation of water seeping out through the tiny pores of the terracotta helped cool the bulk of water inside the pot.

A small brass cup at the end of a long handle, called bhabhka, was used to fetch water out of the matka and into the glass for drinking. Some experts, me included, could drink straight from the bhabhka, without touching it with their lips and making it jootha (contaminated). Also used for storing drinking water was surahi, a smaller, more elegant terracotta vessel with a round belly and long thin neck. While the surface of a matka was generally plain, that of a surahi always had designs on it. Surahis were generally used as personal vessels, one each for every member of a family.

I do not remember anyone we knew having a refrigerator. We stored a slab of ice in an ice box, an insulated container with ice storage in the top shelf and space for cooling things at the bottom. Biji made kulfi at home. She had conical aluminium moulds with screw caps. These were filled with sweetened karrah doodh (slowly cooked and slightly thickened milk) with ground almonds and cardamom. The screwed caps were sealed with flour dough. The moulds were put in a gaagar (a big round brass container with a 4-inch flared neck). Chunks of ice and some coarse salt were then filled in all the space available in the gaagar. The gaagar was wrapped with gunny sacks or some thick cloth for insulation and shaken continuously. All who wanted to eat kulfi took turns in shaking the gaagar.

In about 20 minutes, kulfi was ready. The mould was washed to remove any salt water sticking to it, the seal was peeled off, the cap was unscrewed and the kulfi slid out onto a plate,deliciously cool. Fruity kulfi could also be made by replacing almonds and cardamom with the pulp of the desired fruit. Mango was a favourite.

Favourite summer drinks were thandai (cold milk, spiced with ground almond, cardamom) shikanjavi or nimboo paani (lime juice, sugar and cold water), or sharbat (flavoured syrup in cold water; these could be made at home with several flavours, almond, rose, orange, mango etc.). Rooh Afza, I remember, was a popular red coloured sharbat, available commercially.

During summer we used to sleep on the terrace. After sundown, the terrace would be sprayed with water (chhidkaw), the charpais would be laid and light beddings unrolled over them. Sometimes, it would start to rain in the middle of the night. We had to quickly roll up the bedding, dump it in the landing and go down to sleep on the beds in the rooms, or durries on the floors, fans turning at full speed. The rooms felt like ovens, compared to the cool outside on the terrace, at that hour.

During winter, Hammam was the only means of heating water for bathing and other hygiene needs. One filled about a quarter of a big bucket made of galvanized iron (about 25 litres or 6 gallons) off the hammam, carried it to the bathroom, topped it up with tap water and bathed oneself with a lota or gadvi (a spherical mug with a flared neck and a ringed bottom, made of tinned brass). Plastic buckets had not yet appeared on the market. Bathing in winter was not much more than wetting your body, applying soap, and rinsing it away. The summer bathing was more luxurious; lingering under a tap fully turned open, or under a shower, if there was one.

Every day, a stream of hawkers came to our compound. The day started pretty early with the milk man. He brought a couple of buffalos and a cow right into the open space in the middle of the compound, and milked them there. Every household sent a member with a pan to buy the amount they needed. The milk came warm, straight from the udders with thick froth on top. It was immediately boiled, allowed to cool down and the malai (skin) skimmed off for making butter later.

Although they watched him milk, the mothers always complained that the man somehow had added water to the milk. The malai after boiling it was never as thick and rich as the day before! Complaining about water in the milk seemed to be a ritual which had to be performed. In the beginning, milk cost 4 annas (rs 0.25) a seer (about 1kg, 1 litre or 1 quart). When the man announced an increase to 5 annas, there was a hue and cry. What was the world coming to?

(As I remember, there was no commonly used measure for volume, as liquids stuff such as milk, oil or ghee were also bought, like solids, by the weight measures: 1 maund = 40 seer; 1 seer =4 paus; 1 pau = 16 chchatank; 1 chattank =5 tola; 1 tola 12 masha; 1 masha = 8 rattis.)

After the early morning milk-man, followed a stream of vegetable vendors. They came with all the fresh veggies of the season carried in three different ways. First, a tokra or jhalli ( a big round woven cane tray) with the different veggies arranged in neat piles, carried on the head. A ring, made of rags, 8-inch diameter, and 2-inch thick was worn on the head to protect it from getting sore from the load borne for a long time.

Second, a wooden cart (rehri), loaded with the fresh produce was hand-pulled by the vendor, probably wealthier than the load-carrying ones. Third and for me, the most picturesque, were two tokris [baskets], about 3 feet dia. each, hanging by three ropes from each end of a half-split bamboo pole, about 6-7 feet long.

Each of the tokaris was filled with roughly equal amounts of veggies arranged in piles. The vendor balanced the long bamboo pole on his shoulder and could walk, carrying it like a giant pair of scales. When the vendor reached where he wanted to, or when a potential buyer called, he lowered the load, rested the bamboo on his walking stick, and was free to deal with the customers, the two full trays resting on the ground in their colourful glory.

Buying veggies was another ritual. The mothers berating the veggies (baasi lag rahin hein; the veggies look stale) in the hope to get the price lowered; complaining how much cheaper it was just yesterday; and always accusing the vendor of cheating when weighing the pao (quarter) or aadha (half) seer bhindi (lady’s fingers or okra) or baingan (brinjal or eggplant) or whatever.

Other vendors kept coming the whole day.

“Jamun kaale, kale raah; tinni aane paa…(black, black and plump; only 3 annas a quarter seer…)” used to be the call of the Jamun (Indian blue berry) and faalse (phaalse) vendor. Papaji would put the fruit (jamun) in a lota (mug with a neck), add salt and pepper, shake it just enough to crack the skin, and it was ready to eat. Pure heaven! I did not find faalse anywhere else during my travels around the world; jamun yes, but not faalse.

The kalai wala, the knife sharpener, the mochi (cobbler), patti wale chchole kulche, patti wali kulfi (chcholeare cooked chick peas, kulcha is a soft white bread specially made for chchole, kulfi is frozen thickened milk, the tin containers for these are insulated by wrapping several layers of white cotton strip, resembling a bandage, patti, around them), shakarkandi ki chaat (chaat of sweet potato), chana jor garam (very spicy roasted chick peas), aam- papad(mango juice, dried and rolled into a flat cake), lakkad-hazam/pathhar-hazam churan & reti wala chooran (chooran is a sweet and sour mixture of Indian spices, very nice to lick a little at a time. It is reputed to enable digestion of anything you eat, even wood and stone.

Reti is done by putting a pinch of potassium chlorate on the chooran and then a drop of sulphuric acid on it. This sets the chlorate on fire which burns for a second or so.). Buddi maai ke baal (candy floss), gatta laachiyan wala (cardamom flavoured sugar is converted to a dense and very elastic state. It is also given red, white and green coloured streaks. The vendor takes a small amount and forms it into the shape of a parrot, attaches it on a stick like a lollipop and gives it to the customer to lick. While doing this, he keeps making parrot like sounds with a whistle hidden in his mouth.)

There was thebioscope with baarah mann ki dhoban (a box with 3 or 4 peep holes fitted with magnifying glasses. The vendor can roll pictures of animals, natural scenes etc. One traditional picture is of a fat nude, called barah mann ki dhoban, which literally means washer woman weighing 12 mann or 480 seer.

There were exotic fruits like phalse and jamun, super light papad, so light that if you were not careful, a light gust of wind would blow it away; balloons, tooters and rattlers displayed on a cross-like carrier made of bamboo; and finally, the most ingenious and ethnic of toys: rattle-carts (I do not remember the vernacular name), and sarangi (one-stringed violins)!

Rattle-carts had a small terracotta dish on which a piece of brown paper was stretched taut and glued, turning it into a small drum. This was mounted on a small triangular frame made with split bamboo sticks. The broad end of the triangle had an axel with a small terracotta wheel on each end. When the frame with its dish-drum load was pulled, the axle rotated and actuated sticks which alternately beat on the drum. With a string tied to the pointed end of the frame, the cart could be pulled as you walked. And as you walked pulling the cart behind you, the rattle worked!

The sarangi was a small sound box made with a terracotta dish, brown paper stretched and glued to it. This was mounted near one end of a bamboo stick. A single strand of steel wire tied to the sound box end of the stick was stretched over a bridge resting on the paper membrane, the other end tied to a peg on the other end of the stick. The string could be tightened or loosened by turning the peg. A simple bow made of horse hair stretched across the ends of a small split bamboo stick made beautiful sound when rubbed on the steel wire of the sarangi.

The vendor, generally a woman, carried these carts and sarangis in a basket balanced on her head, pulled a cart behind her as she walked and flawlessly played the latest film tunes on one of her sarangis.

The area where we lived

In the compound, there were several families with children of our age group. There were also a large lawn along the entire length of the front, facing Rohtak Road, and a big unpaved ground between the two rows of houses. We, therefore, did not have to go outside the compound for playing.

Rohtak Road, in front of our compound, started at Eid Gah in the east and went all the way to Rohtak in the west. It was lined on both sides with thick neem trees which provided cool shade.

Going about 500 yards east from our compound, there was an intersection; Ajmal Khan Road to the right and the road to Kishen Ganj , Delhi Cloth Mills, Pul Bangash and Sabzi Mandi etc. to the left. Ajmal Khan (AK) Road was also lined with shady neem trees.

As you turned right on AK Road, there was the huge compound of Tibia College for Yunani Medicine on the right. On the left was the sprawling Ajmal Khan Park. South Park, East Park and North Park Streets lined the other three sides of the park. These roads had up market bungalows along them. AK Road went on for about a mile and a half, crossing the Original Road, the Arya Samaj Road, the Pusa Road and then some.

Other than the neem trees, the Tibia College and Mohan Stores, there was nothing else on the 1 ½ miles of AK Road in April 1946!

By the late 1950s, it had turned into the biggest retail market of Asia; totally transformed by the enterprising refugees who poured in from West Punjab after the partition of the country on August 15th 1947. The authorities permitted them to set up shop for whatever business they wanted. Within days, hundreds of khokhas, rigged up with packing wood planks and corrugated iron roofs, sprung up on both sides of AK Road, from one end to the other.

Entrepreneurs set up whatever business they were used to and comfortable with. There were shops for cloth/wool, tailoring, shoes, books/stationary, cameras/photography, bakery, pakore /halwai, bharbhoonja (person who roasts chana, peanuts and maize in hot sand), chemist/pharmacy, doctor, hair dressing, grocery, fruit/vegetables; in other words, anything and everything you can think of.

There were also small vendors, who could not set up a regular shop, who acquired street-carts or rehris for sugarcane juice/ ganderiyan (sugarcane chunks), chhole-kulche, etc. The memory I cherish the most is of rehris heaped up with delicious lukaat (loquat). The heaps were always decorated with silver tinsel or kinaari.

Others, with even lesser resources, just set up their wares on the floor by the road side. I remember, walking to the neighbourhood bakery, carrying a thali full of atta (whole wheat flour), sugar and ghee, which they would bake into delicious biscuits, while I waited. I also remember carrying a big bowl full of maize to the bharbhoonja to roast it to phullay (popcorn). After sundown, the road used to be blazing with light, all the khokhas shining brilliant lights on their wares. The carts and the foot-path vendors did not have electric connections. They used pressurized kerosene lamps or acetylene lamps which were equally brilliant.

Some vendors had another way of attracting customers; movie songs played at full volume. These were 78 rpm records played on hand-cranked phonographs. Due to over cranking, Lata Mangeshkar’s hit song “chup chup khade ho zaroor koi baat hai….” would start in a very high-pitched Lata song, as the disc turned faster than 78 rpm, and turn into a very base Rafi rendering towards the end, as the rpm speed got less than 78.

In January 1947, my sixth sibling was born. The company doctor, Mrs. Massey, came home to deliver the baby. Delivering babies at home was the common practice then.

Partition and its impact on us

I have vivid memories of the days just before and after the partition. There were communal riots all over Delhi. You could hear slogans of har har mahadev, jo bole so nihal, allah hu akbar all through the day and night. I remember seeing human dead bodies in the nallah (wide, open drainage canal)not far from where we lived. One heard stories of trains full of slaughtered people pulling into Delhi railway station, and similar trains going into Lahore (then, Pakistan).

We got news, I do not remember how, that one of my uncles, my father’s younger brother, was murdered in Peshawar. A mob forced its way into their home, sent the wife and five children in another room, and shot him in cold blood. The news had it that the family was then rescued by other Muslim neighbours and were now on the way to Delhi with a refugee group.

Another uncle, my father’s elder brother (taya in Punjabi) in Bannu, was also on his way to Delhi with his wife and six children, unharmed. My grandparents from Leiah, Dera Ismail Khan, also unharmed, were on their way to Delhi with another group. They all joined the groups to Delhi because that was the only city they knew on the Indian side where they had any place to go.

Again, I do not remember how, but days later my father had located all three families and brought them home. Including us, 5 families, 26 people, under one roof!

Those were tough days. To make 5 families comfortable in a house meant for one family, and to feed them, must have been a tremendous challenge for Biji; but she managed very well. We, the children never sensed that there was any hardship.

I remember my widowed chachi and the elder tayaji made daily rounds of the secretariat in order to follow up on their claims for compensation. Public transport was non-existent. Taxis were unheard of, tongas (two wheeled horse drawn carriage) were expensive; they had to do this on foot, a trek of some 4 miles each way. Almost always the trip lasted a whole day. I remember the look of exhaustion and utter despair on their faces when they returned after achieving, perhaps, no more than just a glimmer of hope promised for the next visit. Eventually, they got due compensation in terms of cash or property, newly constructed by the government.

While the grownups had their challenges, the 17 kids had a great time. This was the first time that kids from Lahore, Peshawar, and Bannu had gotten together for such length of time. Our age range was 16 to 5 years old with one 2-year-old toddler. We played traditional games, exchanged stories, organized skits, and treks to nearby Jamuna river bank or Anand Parbat, a hill where friends lived.

The games we played included pitthoo (seven tiles), gittay (four pebbles, to be picked up in one hand in the time a fifth pebble, tossed up, returned for catching in the same hand), looka chchippee (hide and seek), chicho cheech ganderian (a kind of treasure hunt), bhabo, 3,2,5, court piece (all, card games), and trade (a version of monopoly).

I do not remember how long this situation lasted, when the four families went away to live in their own homes and life for us returned to normal.

Schooling

I got admission into Sir Harcourt Butler Higher Secondary School. It stood on Reading Road (now, Mandir Marg), adjoining the Birla Mandir (or Laxminarayan Temple). My older sisters got into Queen Mary’s School. The younger ones went to nearby Vidya Bhawan for a few years, before they too joined the Queen Mary’s.

Vidya Bhawan School, where my younger sisters went for a couple of years, was just past the Pusa Road crossing. The only commercial establishment on AK Road then, was Mohan Stores. It was a general-provisions store and stood on the left side about 500 yards from the Original Road crossing as you walked towards Pusa Road.

My older sisters and I rode our bicycles to school. No bicycles were manufactured in India; “Hercules” came a few years later. Philips, Raleigh, and “Rudge” were the popular imported brands.

My school was about 3 miles away. I rode east to the end of Rohtak Road at Eid Gah, and then turned right down Rani Jhansi Road towards Panchkuian Road. Eid Gah sat on a little hill, climbing up to there was some effort but from there up to Panchkuian was downhill and I did not have to peddle at all.

During my school days, the end of Rani Jhansi Road where it met Panchkuian in a T-junction had some curious features. There was a grave right in the middle of the road; it was a protected feature. The up and down traffic had to go skirting it. There was a cremation ground on the right-hand side and the building of Jamia Milia Islamia right in front. Now, there is no sign of the grave, and the Jamia Milia Islamia has moved elsewhere. The cremation ground is still there.

I turned left into Panchkuian and then right into Reading Road. There was little vehicular traffic in those days, an occasional motor car, tonga or lorry; mostly bicycles and pedestrians. At that time of the day, Panchkuian Road was a river of bicycles flowing towards Connaught Place. Babus, in their hundreds, riding to their offices with their lunch boxes secured on the carriers behind them, headed towards the secretariat buildings.

My school was about ¾ mile from there, just before Birla Mandir and adjoining it. It is still there, but Reading Road is now Mandir Marg. Then, as now, this road was lined with schools on its west side. The east side was lined with residential quarters of junior government employees. These were built as modest single storey houses arranged in rows around a square playground in the middle. They were named after British bureaucrats, e.g., Jeffery Square, Clive Square, Wellesley Square etc. They were all identical looking and painted yellow.

At the back of the school was a multipurpose playground, extending west to touch the east edge of Delhi’s Central Ridge. The ridge was barren and rocky but thorny babool trees as well as thorny bushes bearing delicious edible berries (baer) flourished there.

Soon, at school, I met class fellows who lived at East Park Road and Arya Samaj Road, both in my neighbourhood, and also rode bikes to school. We decided to ride together to and from school. For me, this meant changing the route. We would congregate at Arya Samaj Road, ride east to the top of the hill where the Hanuman Mandir stands now, and roll down all the way to Panchkuian which we reached at the cremation ground/grave-in-midroad/Jamia milia Islamia junction. Sometimes, for a gentler downslope we would take the right diversion through Bhuli Bhatiari. On the way back, since the climb up was a lot of effort, we would walk up the slope, dragging our bikes with us. An enterprising refugee had set up a pakora shop at the beginning of the slope. He fried delicious pakoras and we invariably got tempted to have some before the climb.

At school we had a tuck shop where one could buy snacky food for lunch. It had the most delicious samosas; one anna per piece. Many kids ate there. But, Biji did not want me eating that “rubbish”. She would pack lunch for me. Mothers of some other buddies did the same.

During lunch, some of us would get together, cross over to Birla Mandir and have our packed lunches in one of the gufas (caves) there. Other than temples for various deities, Birla Mandir had many fun things for visitors, especially children. One such feature was a number of small gufas with openings in the shape of mouths of giants or ferocious animals. If there was time left, we would cross over to the Ridge, Pahari, and pick baers off the bushes there.

During 1948, riding my bicycle to school, I would see municipal workers spraying something around houses and over open drains. Later, I learnt that it was DDT against malaria-bearing mosquitoes. During the same year, there was also a campaign for mass vaccination of BCG against tuberculosis. Both these campaigns were very successful. Malaria and TB were eradicated in India, until their resurgence in recent years.

After partition, with the influx of refugees, there was a shortage of schools and colleges. Many schools, including ours, doubled up as Camp Colleges to cater to college going refugees, living in refugee camps, whose education had been interrupted. The college would run from 7-10 a.m., and again from 5-8 p.m. The school ran in the interim 6 hours from 10:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. with a break in between. I do not remember how long this arrangement continued.

Science and Sanskrit were added to the curriculum in the seventh class. In the ninth, students in the science stream did the final year for Hindi/Urdu. Science was split into physics, chemistry and higher mathematics. New subjects, biology or engineering drawing were added. Biology intended for those planning for a medical career, drawing for the future engineers.

In the middle of summer, when there was a cloudy day, we used to call for a fine-day relief. (In the cold western countries, a fine day is a bright and sunny day while a day with overcast skies is deemed dull. For us in hot India, it is the opposite. Such is the influence of weather on the local culture, behaviour and psyche).

Most of the time, our request was accepted and we would go, accompanied by a teacher, riding our bikes to Okhla, by the river Jamuna. There was little traffic and most roads were lined with thick and shady mango and jamun trees on both sides. It was a pleasure riding your bike along these roads. We went even further, to Kutub Minar. ‘Who could climb the stairs (more than 300, I remember) all the way to the top, in the shortest time’ was the favourite competition. Entry to the minar was later banned after some young people committed suicides following frustration from academic results or amour.

I used to bicycle all over Delhi, with a friend or two riding along. In those days, the limits of the city were Okhla to the east, Nizamuddin to the south, Pusa Hills to the west and Civil Lines to the north.

Neighbours

Our neighbours in number 11 were Parsees, the Nariman family. Their two sons, Daraius and Mickey, a couple of years younger, were very proud of originally being from Bombay. A ditty they sang often is still fresh in my memory. It went,” B-O-M, B-A-Y; Shout, Shout; Hooray, Hooray; We are the boys, we are the boys; Happy every day; Bom Bom Bom Bombay.” They liked to play with me; I too, because they owned an air gun.

One day we decided to go bird shooting on Anand Parbat. The parents agreed and we set off pretty early in the morning. Anand Parbat was a hill, rocky and full of thorny bushes. Soon after we started the climb, the younger, Mickey, fell and badly hurt his right thigh on a sharp stone. We could see a gaping wound, white flesh inside quickly welling up with blood. I, the oldest, and keen not to let anything jeopardize a day out with an air gun, tied a hanky tightly over the wound, stopped Mickey from crying with a “men do not cry.” and we resumed our hunt. We went around taking several shots at sitting birds. Not one was hit. Pretty tired after a couple of hours, we returned home with no trophy and Mickey limping. The scolding I got from the Narimans and my own parents!

Another unforgettable family were the Soods; Mr. and Mrs Triloke Nath Sood lived in no.8. Mrs. Sood was a teacher in the Elizabeth Gauba School. Some years later, one of her students, Suhas Pandurang Sukhatme was my class fellow in Mechanical Engineering at the Benaras Engg. College. He topped the class (I was 4th) in the final year, went on to do Sc.D. from MIT, returned to teach at IIT Bombay, became the Chairman of the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board, and earned a Padma Shree.

The Sood extended family often came to stay in our compound. The eldest brother, Mr Pran Nath Sood organized the compound kids into a sort of club. He, with his younger sister Shiela bhua (aunty) would arrange various events, such as sports and art competitions, stage performances etc. We coined the title “Founder Saab” for him. The family was very fond of me. The youngest brother, Capt. Rajinder Nath, would take me, as a guest, to the Defence Services Club near India Gate, to teach me swimming. I quite enjoyed it and learnt it fast.

One summer day, I coaxed my childhood friend (from Lahore days, sadly, died a young 58) Daman Malik to come with me for swimming. Daman was a couple of months younger. I was smarter in studies, but Daman beat me in almost everything else, fist fights, sports, kite flying, street smartness etc.

Daman could not swim; I did not know this and he would not admit it, because then he would be that much less than me in a sport! So, we bicycled away to the Defence Services Club. I signed us in, inappropriately, in the name of Capt. Sood, though not accompanied by him. Other than us, there were only one more couple relaxing on the chairs by the pool side and the club bearer.

I dived in the shallow end and surfaced near the deep. When I looked back to see where Daman was, I saw him, eyes and mouth wide open, desperately flailing at the water, but sinking. It took me a few moments to realize what was happening. By the time I shouted for help, Daman had disappeared under water. It took the bearer, an expert swimmer, who jumped in with his clothes on, two attempts to bring Daman out. The bearer put him face down, stomped on his back to get the water out and continued stomping till Daman threw up and started to violently cough and breathe again.

Our parents were telephoned; Daman’s father came, rewarded the bearer, and took his son away in a taxi, his bike in the taxi’s trunk. I was left to be chided by the other couple and the bearer. I rode back my bike, expecting the worst from Biji and Papaji on reaching home. Surprisingly, Papaji did not scold me, most likely because Biji had been working on him while I rode home.

Games we played

There were enough boys in our compound, around my age, to form a cricket team. During one summer break, I organized the team. The first task was to prepare a field with a pitch. There was an almost flat area, sufficiently large, in the middle of the compound between the two rows of apartment buildings littered with construction debris. It took us two days to clear all of that and pile it in two neat piles further away. Making the pitch was more challenging. The 6- foot wide and 22 yards long strip had to be level, flat and without any pits. My army of 8 to 11 year olds, armed with no more than one spade and a few kitchen tools (which our mothers reluctantly lent us) did that in about a week. We were very proud of the result.

No one had enough money to buy the kit. We improvised. For wickets at the batsman’s end, we used the electric pole which was thick enough and luckily happened to be there, at the right spot; for the bowler’s end we used a brick as a marker. With a big kitchen knife, our household help shaped a plank from a packing crate into a bat for me.

We decided leg guards and gloves are for sissies; we did not need them. Footwear for most sports was the “Fleet” shoes made by Bata. These had rubber soles and canvas uppers and came in two colours, white or slightly cheaper ochre. If you owned a pair, fine, otherwise chappals or whatever your mother gave you was good enough. The only thing we had to buy was the ball. A proper cricket ball, since a tennis ball was for sissies again. We all contributed a few annas each to collect enough money to buy two cricket balls.

I was “elected” the captain, or rather the kids were made to elect me, because, first, the team was my idea, and second, I brought the bat, albeit homemade.

Our first game was a hit. All our families watched from windows, sitting on the boundary wall, or just standing around. Great fun and spectacle! Soon we managed to acquire real stumps and a real bat too.

Then, as now, we were great cricket fans. Lala Amarnath, Vijay Merchant and Nawab of Pataudi were the Indian heroes, soon to be followed by Vijay Hazare, Vinoo Mankad, and Rusi Modi. India, then, were not among the top cricketers. I remember test tours by the MCC (The Marylebone Cricket Club) during two consecutive seasons; and one by the West Indies, with the great Walcott, Worrell and Ramadhin, after that.

Going to watch the cricket matches live at the Ferozeshah Kotla Grounds was expensive. So, we used to be glued to the radios for running commentaries. Voices of Commentators like Vizzy (Maharajkumar of Vijayanagaram), Barry Sarbadhikari and Devraj Puri still ring in my ears. One season, the schools had a special deal and I could get a season ticket (five days) for 5 rupees, a whole month’s pocket money!

Immediately after returning from school, I had a quick glass of milk and ran down to join the boys for the evening outdoor activities, which could be cricket, gulli danda (a small whittled stick sprung and hit with a longer stick), kanche or bante (marbles)kho-kho, or football. We would lose track of time. Our parents had to call out to us for the evening meal.

One time, I got so addicted to playing kanche and spent so much time on it that I failed the mid-term exam. Biji was very upset. I begged her not to tell Papaji. She said she will not if I promised to give up kanche altogether, work hard and do well in the final exams. I did. The elder Mr. Sood, Triloke Nath’s father, coached me in Math. It worked so well that I passed the final exam with distinction.

Entertainment

There was no television yet. So, the after-dinner routine was to listen to the radio. All India Radio used to have radio plays which were quite interesting. There were other features like news, bachchon ka program (program for children), behenon ka program (program for women), and often there were arguments among the 6 children and two parents as to which program to hear on the one radio available.

We were also crazy about comics. These were expensive and not easy to obtain. Whoever managed to get one became an instant most popular person in the compound. I fondly remember, the super heroes: Captain Marvel, Mary Marvel, Marvel Junior, The Marvel Family, the western heroes: Tom Mix, Hopalong Cassidy, Gabby Hayes, the classics: Les Miserables, Count of Monte Cristo, and the rest: Richie Rich, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck.

While the classics aroused some hunger to read the real works, the others were my earliest insight to the American way of life. Through them, we learnt about blue jeans, lumberjack shirts, sneakers, baseball caps, bubblegum, hotdogs, hamburgers, triple sundaes, Lionel trains, B&B air guns, the greetings Hi, Howdy, and terms gottcha, bonanza, green backs, critters, injuns, paleface, cowboy, ranch, attaboy, “I dunno nothing”, “them wuz the days” and many more.

Often, on summer evenings we would go for a picnic to the India Gate lawns. Other than lush green lawns where children could play, there were vendors for Kwality ice cream with their iconic carts, and those for chana jor garam singing their unique praises, competing to sell their ware.

I still remember one such song: mera chana bada hai aala, usme daala garam masala, jo bhi khaye kismet wala, woh ban jaye afsar aala (my chana is super good, hot condiments have been added to it, whoever good fortuned enough eats it, will become a big officer). Later, there were facilities added for rowing small boats in the canals along Kingsway, now Raj Path.

Kingsway started on the west at the viceroy’s estate with the grand fountain in front of it, and ran east, past the beautiful circular parliament and other secretariat buildings, around the India Gate war-memorial towards the statue of King George V.

Rather rundown today, Connaught Place, CP, was a posh and beautiful shopping, cinema and restaurant area until the sixties. In 1946, the outer circle, Connaught Circus, was one of the few places, if not the only place, in Delhi with traffic lights at crossings. Turning left from Panchkuian into Connaught circus, if you maintained the permitted speed of 25 mph, you would meet green lights at all 7 radial road junctions going around it.

Walking in the veranda along the inner circle, window shopping and peeping in the doors of restaurants to spot familiar people was fun. For me, some unforgettable names are Volga, Embassy, Nirula’s, Palace Heights, York, United Coffee House, Kwality, Gaylords, and Wengers. Cheese balls, pineapple cakes (pastries in vernacular) and cold coffee in Volga, and chhole-bhature from Kwality were special.

Gaylords and Volga had “Jam-Sessions” for 1 hour every Sunday from 11 am to 12 noon. Nothing to do with jam, these were western music and dance sessions with live music, for teen agers. Jam-Session birthday celebration by friends was considered very special.

CP cinemas, Plaza, Odeon, Regal and Rivoli brought foreign (British and Hollywood) movies. After 1950, though, due to foreign exchange restrictions, these imports were severely restricted.

Baba Kharagsingh Marg was Irwin Road. Kasturba Gandhi Marg was Curzon Road and Janpath was Queensway.

D.C.M. had their own movie theatre, primarily for the non-supervisory staff. The ticket for a show was 2 annas. Because we were officers’ children, we would often succeed in making our way in for free. If the audience liked a particular scene, they would shout “once more” and the operator would roll the film back and play it again.

Budding engineer

I was fascinated by science and also liked to tinker with home appliances, attempting to repair them. Sometimes the thing got even worse than before, but more often, I succeeded in the repair. There was a kabari bazar, near the Jama Masjid. I was a regular visitor there and bought many WWII surplus things for my repairs or small model making. It was also possible to buy chemical reagents and laboratory items like test tubes and flasks for small experiments at home. I would salvage zinc and carbon rods from used Eveready battery cells and use them for making electrodes for my home-made cells.

I remember making a crystal-set for radio receiving; an induction coil; a small electric motor; and a rocket with an empty cigarette tin, powered by calcium carbide bought in a grocery store, and water. I also remember making a patakha (cracker) with a key, a nail, and a match-head as gunpowder. The match-head material is stuffed in the hole of the key, the tight-fitting nail is inserted and then, when the nail is hit with a hammer, the material of the match-head (Sulphur, phosphorus, etc.) explodes.

Favourites for repair-at-home were toasters, electric heaters and table fans.

Driving a car

In 1950, D.C.M. started a scheme to offer interest free loans to its officers. It could be used to buy a vehicle; a motorcycle or a car. My father made use of it to buy a Vauxhall Wyvern. I remember the price; Rs. 9,950. It was a good -looking car, beige in colour. We named it My Fair Lady. Together with my father, I too learnt how to drive it. I was far short of the legal age (16, I think), did not have a license, but was driving the car. When I came of age, my driving license arrived home, without my appearing for any test whatsoever. I remember the registration number of our car, DLB 6499.

Petrol was 12 annas (Rs 0.75) a gallon.

Owning a car was rare. We were among the first in our compound to own one.

Having a telephone

Another rarity was owning your own telephone. Ours came, given by Papaji’s employer, in 1951. The number was 26898. I remember that by dialling the number 6, you could get a recorded voice telling the correct time of the day; “at the sign of the tone, the time will be xx hours, xx minutes and xx seconds ... ping”. This was repeated every 5 seconds. We also discovered a trick; lift the receiver, dial two digits (I have forgotten which), put the receiver back on the cradle and your own phone would ring. You did this, ran away and watched someone run to the phone to pick up the receiver, keep saying hello, hello to no one at the other end and finally bang the receiver down with an under-the breath curse.

Goodbye, Delhi

In 1953, I passed the Higher Secondary examination, i.e., the 11th class in school. I sought and obtained admission to the Intermediate Science College of Banaras Hindu University (BHU) and went away to study there, followed by the Engineering College there. I visited home in Delhi during the summer and Diwali holidays, but my touch with Delhi was mostly lost.

Soon after graduating from BHU, I went to Bombay to pursue my professional career.

____________________________________

© Mahen Das. Published February 2021.

Comments

Your memories

Wow! what a continuation

Re: Correction

Add new comment