PWD Administration in UP

Category:

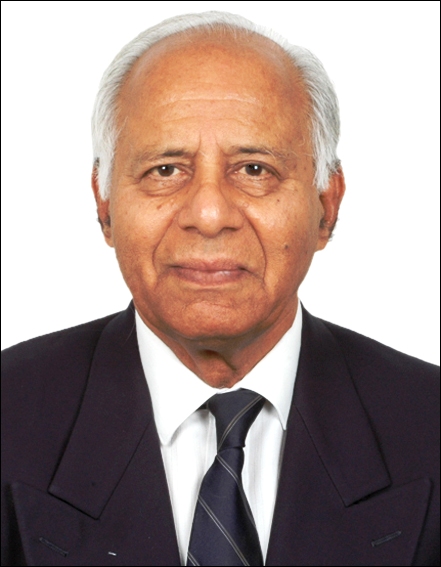

Born in Lahore on 5th January, 1930, to Savitri Devi and Shanti Sarup and brought up in an open environment, without any mental conditioning by a denominational commitment. He imbibed a deep commitment to democracy and freedom because his family participated actively in the freedom struggle. In 1947, together with his family, he went through the trauma of losing all, and then participating in rebuilding a new status and identity. He Joined the IAS in 1954 and retired in 1988 as Education Secretary, Government of India. Later, he became Chairman, National Book Trust. Also co-authored, with Sulabha Brahme, Planning for the Millions.

Editor’s note: This is one of several stories about district administration and officials in Uttar Pradesh in the 1940s-1960s.

It was February 1968. The wind was cold, and the chill was accentuated by the isolation of the place the five men were stuck in. The road between Ranikhet and Kathgodam had been blocked near the iron bridge leading to Garam Pani, Bhowali, the famous sanatorium.

They were the personal staff members of senior officers returning to Kathgodam from a conference in Ranikhet. The senior officers had managed to get escape the blockade by walking across the bridge, leaving their heavy luggage and bulky papers with their staff, who would bring it later when the blockade was lifted.

The staff, powerful in their own jurisdictions, were somewhat at a loss in this remote place. Till the blockade was cleared, they had to somehow manage their lives with locally available provisions and accommodation. They had got hold of whatever was available with a Forest guard. It was not much - just some bug-infested charpoys, a table lamp and a lantern. And there was someone who could light a fire, cook them a frugal meal, and do odds and ends.

During the day, these five men could while their time by playing cards or keep looking out for news about the lifting of the blockage. But, by 6.00 o'clock, darkness enveloped everything. The meals were served in rough metal plates by the ‘host' who was anxiously awaiting their departure. He was a doleful character. Not cheerful company.

On top of it, he advised every body to stay indoors at night. His stories about leopards and tigers, which infested the area, scared the five men. They were unwilling to venture outside more than ten yards from his doorstep. There was an oppressive feeling of being under duress.

Fortunately for this group, a grey haired old man, Ram Singh Bisht, turned up with a gun in one hand and a whiskey bottle in the other. He too was feeling stymied by the blockade, and wanted some company. He could not go even to nearby Bhowali for his newspaper and his daily provisions. He told the visitors that he decided to bring a bottle of whiskey because it wasn't any use to him without them because he never drank alone. The five men greeted this with enthusiasm because now there was a welcome diversion from doing nothing and just waiting uncertainly for deliverance.

Their joy was greatly enhanced when Bisht told them that he had retired as a stenographer to the District Judge of Nainital in 1955. Since most of the visitors wee also civil servants, Bisht was a person of their kind, with whom communication would not be a problem.

Soon, Bishtji opened up with his stories about his favourite District Judge, who was unusually strict and honest but was also a little peculiar in his daily life.

Editor's note: Bishtji's story about the Judge is presented in Judge Saheb - Judicial Administration in UP.

Superintending Engineer

After Bishtji's story about judges, it was the turn of Radha Krishna Gupta, a wizened old man who always wore a silk shirt. Guptaji was the P.A. (Personal Assistant) to a Superintending Engineer (SE) in the Buildings &\; Road Division of the Public Works Department (PWD).

He explained that a SE was a powerful man whose illegal income usually exceeded the takings of the District Magistrate, the District Judge and even the District Superintendent of Police. This was because a SE supervised what was spent in the districts or collected as revenue by Executive Engineers (XEN), who were his subordinates. The SE was not responsible for the execution of any work or directly for collection of revenues. These tasks were performed by the XENs. An SE was charged with the responsibility of spot inspections and for holding inquiries, on his own or when there were complaints that an XEN was harassing contractors or allowing them to get away with poor quality of work. According to Guptaji, an SE, by convention, was called Rai Bahadur Saheb because, during the British Rule, this ‘honour' was conferred upon a person who rose to this position.

Guptaji said that in engineering circles there was a variable scale of illegal commissions that contractors had to pay to get the engineers to finalise the payment of the contractors' invoices. Whenever the SE went out on tour, at every Inspection Bungalow on the way, a lavish meal (lunch, dinner, and high tea) was spread out so that if Rai Bahadur Saheb happened to stop anywhere on the way, he would have no problem for his meals.

The SEs are people with experience. They come up step by step from Assistant Engineer to XEN, and then to SE. Most of them have links not only with the politicians but also with state level bureaucrats. They seldom accept gifts directly from the public. What is more, an SE would consider it below his dignity to accept paltry gifts. Since they know how much illegal commission would be coming to the XENs, they can calculate what they would get at the rate of three percent of it, of which one and a half percent goes up to the Chief Engineer's establishment.

At the level of the Chief Engineers, who are the top bosses in the PWD, crores of rupees come up without their doing anything. Of course, they have to keep the state level officers and the powerful ministers on the right side. It was well known that a PWD Minister gets roughly one percent of the Plan Budget for his political and personal business. Beyond this, some money comes up the spiral when a contractor pays up a hefty sum to suppress complaints about his bills or his work.

Guptaji said that his present boss wasn't a rich man to begin with. He came from a family of a Tambolis (tobacconists) who had realised that they had a very promising son. His father had borrowed money at a high interest rate to pay for his son's education at Roorkee Engineering College. The boy did very well in his studies, securing the third position in his final examination. As was the established practice, the young man was straightaway appointed to the State Engineering Service.

Immediately after this appointment, the family was inundated with generous offers from well-to-do fathers of marriageable age girls if the young man married their daughter. Some of the fathers were willing to reimburse the family for the expenses on the boy's education, give a suitable dowry including a house of his own to settle down, and even pay for the wedding expenses of one or two of his sisters.

In the end, the young engineer was married into well-to-do family, which had many friends among powerful politicians. Two of his wife's brothers grew up to become politicians in their own rights. One was a Congressman and the other was a Janata Party MLA. This, according to Guptaji, provided his boss, with a lot of political protection. Though Rai Sahib paid the customary tribute to his political bosses, no politician dared to make extraordinary demands from him. What is more, he always got promoted without much trouble.

The SE sahib was an easygoing gentleman who liked his game of Bridge and his favourite Scotch whiskey (Vat 69). Once in a while, he visited a courtesan. Somehow, his wife came to know about these extraordinary adventures, which gave her a handle to take control him and his wealth. The fact that she did not have children made her particularly insecure. So much so that when he got a chance to visit England for a year, she saw to it that she also went with him. She came back with a gold cigarette holder and packs of State Express 555 cigarettes.

Over a period of years, she set up her own network of informants who told her whenever he visited someone she did not approve of or had a windfall from an inquiry about an XEN or Assistant Engineer. His subordinates did not take long to learn about who wore the pants in their home and always came to her if a matter could be settled at his boss's level of authority, knowing well that she would suitably influence his decision.

She was greatly upset when her husband was not promoted to Additional Chief Engineer in spite of all her efforts and the active support of her brothers. Whenever a promotion opportunity opened up, it was customary to promote a candidate by publicising his good qualities, spending lavish amounts of money, and running down other competing candidates with all sorts of true, half-true and completely false allegations. This kind of free for all gave the political bosses the justification to intervene and promote their favourite.

At this point one of the listeners to the tale asked Guptaji if all the PWD engineers were like his current boss. Guptaji said that a nondescript person had beaten his boss, against all odds, in being promoted to Additional Chief Engineer. The winner had neither political patrons, nor much money and almost no place in the network of powerful patriarchs. To top it all, there were complaints about his poor management leading to heavy losses in a bridge over the Ganga near Haridwar. Apparently, he got the support from the Secretary PWD, the top civil servant of the Department.

The Secretary had just arrived in Lucknow from New Delhi. He went to the site of the bridge construction, and decided that complaint had no basis. Guptaji's boss was saved from the disgrace by the personal intervention of this unsophisticated Secretary.

Even though he had failed to make it to post of Additional Chief Engineer, Guptaji's boss was happy. With this failure ended the domination of his wife who had planned and plotted for his rise to this post.

Additional Chief Engineer

The newly appointed Additional Chief Engineer proved to be a pain. On religious grounds, he wanted to break away from the conventions of the percentages of bribes most of his junior and senior colleagues received out of the system. All his colleagues were aghast. All of them were religious but no one let his religious beliefs come in the way of accepting illegal money.

Apart from being clean as a whistle, the new Additional Chief Engineer neither smoked nor drank alcohol, and always dressed inconspicuously. He spent half his salary on books on structural engineering and on project formulation and management. Anyone else might have complained but he never said a word about his wife spending half her time with her parents. When queried, he explained that, in the contemporary world when so much was happening in the world of management and projects, a specialist in Bridge construction could not afford to become out of date. He had just floated the Bridge Construction Corporation and handed over the construction of all the major bridges of UP to it. This step too was seen as a big blow to the illegal incomes of the PWD engineering fraternity, as they would no longer be involved in the construction of major bridges.

In the course of the next six years, the Uttar Pradesh (UP) Bridge Construction Corporation had constructed most of the major bridges in UP. When its staff and infrastructure was on the point of becoming idle, the Additional Chief Engineer and PWD Secretary got the UP government to allow the Corporation put its spare capacity to profitable use by taking up major construction projects outside the state.

Although the new Additional Chief Engineer was not able to inculcate his strict ethics among the personnel of the Bridge Corporation, it was widely recognised as a comparatively honest and efficient organisation all over the country. It was considered cost effective largely because it did not follow the style of working of the PWD, which was notorious for its overstaffing.

PWD working style

In the PWD, it took three people to hammer a nail into a wall. One person carried the bamboo ladder, another carried the bag of tools, and the third climbed the ladder and fixed the nail on the wall. This is how the PWD Secretary had described the working style of the PWD!

Guptaji confirmed that the PWD never said no to any proposal to construct something, even if the proposed budget was too small. It was because they had learnt by long experience that if they said no, the proposed project would be awarded to some contractor, who would accept it knowing that costs could be inflated later. A PWD engineer judged his importance not on the basis of works executed but by the bulk of work taken up in his division. It was strange that the strength of the staff was determined by the aggregate cost of projects in hand.

The PWD engineers loved projects involving a lot of earthwork. It was so difficult to check on the earthwork done on a project two or three years earlier. Much of the earthwork is washed away in rains: how much is anybody's guess.

Pre-Independence

Seeing that his audience was getting weary of his unending stories, Guptaji decided to enliven the end of his narrative with a juicy story from Pre-Independence days. In 1945, a clever Assistant Engineer had reported that earthwork worth more a lakh of rupees - a huge amount of money in those days -had been done to save a particularly important bridge. This claim was met with a lot of scepticism and criticism. The government decided to hold an inquiry into the matter.

First the XEN, then the circle SE and thereafter the Collector confirmed that the earthwork had been done. Yet, the allegations of payment for fictitious work persisted. To put a final end to these, the government sent an ICS Divisional Commissioner - a Scotsman, for an on the spot-checking. Editor's note: The Indian Civil Service (ICS) was pre-Independence India's premier administrative service. It was replaced by the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) after Independence. This worthy came with a resolve that he would walk over the earthwork road and thus put an end to the persistent complaints.

He arrived, at the height of the rainy season, accompanied by the Collector, the SE and the local Tehsildar and set up camp at the PWD Rest House. Because of the pouring rain, he could not go to the spot for inspection on the first day. So, he stayed overnight and was feted with Scotch whiskey and choice meats during his overnight stay. Next day, the downpour only got worse: so he couldn't go and the fete continued with greater vigour with sincere expression of regrets for the inconvenience caused to everybody.

The rain continued as vigorously on the third day. This time, the inspecting party went out on elephants but had to return to the camp without being able to reach their destination.

Next day, the inspecting party found their vehicles were lined up for their return journey. The Scotsman was livid at the affront and demanded an explanation. This time, the Assistant Engineer asked the Tehsildar, the local administrator, to explain. He nodded his head wisely, and said:

"Gentlemen you have been seeing the earthwork road for three consecutive days. This is the road on which the chickens travelled, the Scotch was transported and all the provisions came. How can you say that you did not see the earthwork road? You have to be realistic and recognise and report things as you have seen them and not look for a literal verification."

The inspecting party accepted the ‘truth' of the Tehsildar's statement. It was finally reported that indeed, the Commissioner had verified the existence of the earthwork road and thus, the inquiry came to an end.v

Now in 1968, the District Magistrate and Collector has become an anachronism, said the P.A to the District Magistrate and Collector, Farrukhabad.

Editor's note: The story about Collectors is available elsewhere on this site.

© Anand Sarup 2011

Comments

Add new comment