Memories of Amritsar Medical School

Category:

Tags:

Dr. Prabodh K Gupta attended Government Medical College Amritsar, and the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, with additional training at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. He specialized in Cytopathology. He was a professor at the Johns Hopkins University, and the University of Pennsylvania, from where retired in 2016. He is recognized internationally as a gifted clinician, educator and investigator. He has received numerous awards, including the highest awards by the American Society of Cytopathology (The George Papanicollou Award) and the International Academy of Cytology (Maurice Goldblatt Gold Medal).

Editor's Note: This is an excerpt from the author's book My India My America: Success Yatra available on Amazon.

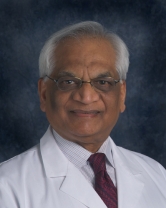

Admission to medical school was a sublime joy. With its promises, opportunities, possibilities, challenges, and fears, this 1955 medical school matriculation was a game-changer and transformational. This is one of the oldest medical schools in the country that started in Lahore in the year 1864. The medical school was shifted to Amritsar in the year 1920. This medical school awarded the LSMF diploma (Licentiate of State Medical Faculty) after four years of schooling\; it was upgraded in 1943 to award MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery, US MD equivalent degree). It was named Glancy Medical College in honor of the Governor of the Punjab State at that time. This medical school was renamed as Government Medical College after partition in 1947.

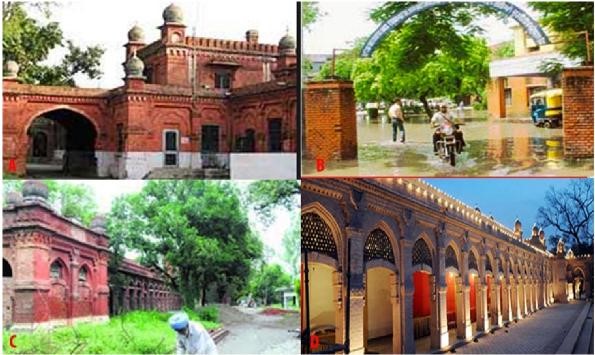

The medical school campus is large, over 150 acres\; Medical School buildings and the residential hostels are separated from each other with a large playground. We could play cricket, football, and field hockey\; eight tennis courts were available at one end of the field, along with basketball and volleyball facilities. The Medical school is situated in a pristine area between circular and Majitha roads. It was affiliated with several hospitals, including Victoria Jubilee (VJ), Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat, and Women's Hospital, a TB sanatorium, an infectious diseases hospital, and a mental institution. It was a large campus with several red brick buildings. Administrative offices anchored the front end of the building while the Anatomy department was at the far end bordered by another road. It had easy access to the morgue and anatomy dissection hall. The front wing had the lecture hall and the anatomy showcase, the anatomy museum, and some administrative offices.

Government Medical College, front entrance (1), Back entrance (2), Administrative block (3), Cross wing (4), Front of the Medical School with anatomy department and lecture halls (4).

The laboratories for physiology, pathology, and pharmacology were in the parallel wing behind the front building. Separating these two parallel sections was an enclosed courtyard often used for student social functions. There was no student hall or auditorium in the medical school facilities. There were no water fountains in the medical school. We used monocular microscopes utilizing the daylight for illumination. Many times, we would rotate the mirror to watch the girls in the lab instead of the assigned glass slides. It was torture\; we were required to draw color pictures of the microscopic fields. Occasionally, the instructors would stop by to quiz us or help with the observations and interpretations of the tissue sections.

We lived in the boys Hostels A and B Blocks.

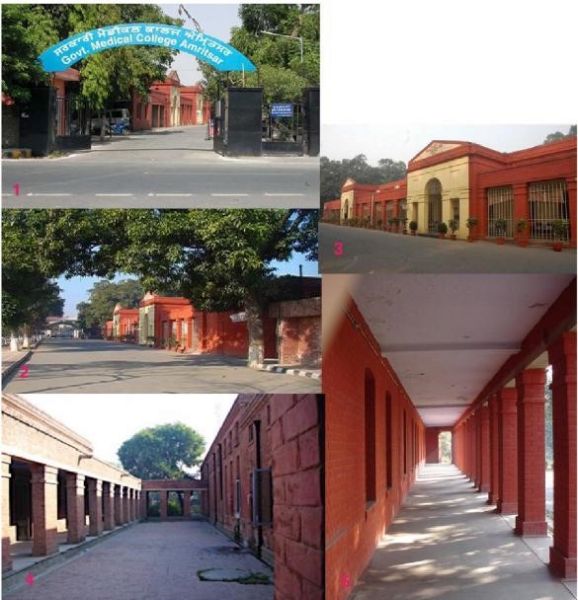

Hostel B Block (2005). Inside, the courtyard, living rooms dining rooms are in front (1). Front iron gate, one of my class fellows (Dr. Kalia) trying to scale it (2), back corridor (3), milk delivery (4), wood-burning cooking pit kitchen (5).

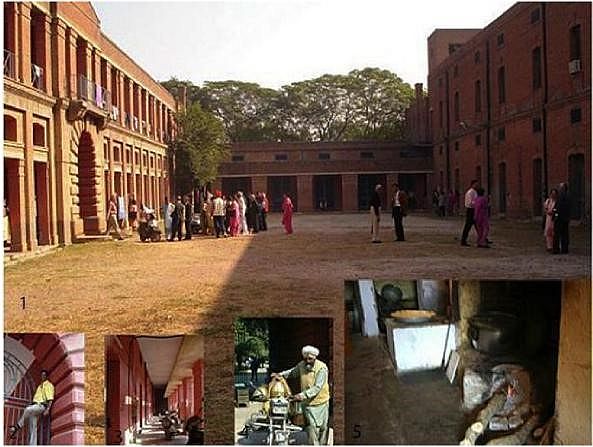

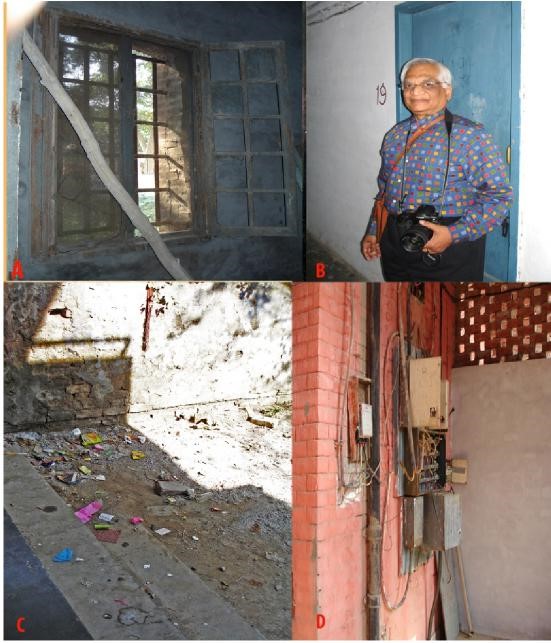

These were like fortresses with large, iron gates and rods as screens on the windows. The rooms were 16X16 feet on two floors. Our toilets were outside the main buildings and about 300 feet away\; however, there were communal bathrooms at the end of the hallways. Using the outdoor facilities, especially during the winter months, was torture. Some of the students kept a chamber pots under the beds. We were housed four to a room in the first year, three to a room in the 2nd and 3rd, and two in the 4th year. Only in the final year did we have a single room in a new hostel now called Block C. Obviously, there was no privacy in these communal living arrangements. Only on days were male visitors allowed in the hostels. There was a large, central courtyard with dining rooms at one end and a common and game rooms at the other. The common room had one tennis table set up, a few carom boards, a radio, and a few "Goodwill" sofas and chairs.

Hostel B Block (2005). Inside, front (A), Back corridor parking (B).

The dining rooms had large, cafeteria-style wooden tables, often cleaned with dirty, soiled rags. At dinner time, rotis (baked Indian bread) were stacked on a plate and eaten not by numbers but by the height of their pile on the plate, two to four inches or more. Sunday lunch was a special treat with minced meat and mulli (daikon) stuffed Paranthas, banana, and yogurt raita often served in sixteen-ounce, large tumblers and some sort of dessert. Often, the afternoon tea was brought to the room and shared with friends. It was not uncommon that each one of us was billed separately for the total charges. Midnight snacks, most of the time, included eggs, or more commonly, an ice-cold brick of Polson's salted butter. It really tasted very good. As youths, we ate well and a lot. Often, we would go out and run around the playground to get some wind, fresh air, and stress relief.

The dorm rooms did not have ceiling fans\; we rented them starting April 15th each year. We were not allowed to use immersion heaters to boil water for tea and coffee. The college gave us a solid three-by-three-foot rosewood table, a steel tubular chair with cane woven seats, and open shelves. We bought our own beds, linens, and table lamps. While the clean laundry was kept in steel trunks, dirty clothes were piled under the beds.

There were a few luxuries\; a barber would give you a daily shave while still in bed, and mess boys would line up with breakfasts outside the lecture hall for us to eat before the professor drove in for the 8:00 am class - a tough job in the brutal Amritsar winters where temperature often plumed to below zero. There were no overcoats or heat, heaters were not permitted in the rooms with power shortages.

Battling the harsh winds, we rode our bikes to the VJ Hospital at 9:30 am using poorly constructed leather gloves, and white coats as over coats. Mess managers were our housekeepers and dealt with all monies and problems\; we trusted them. There was a canteen for late night snacks and food, serving as a hangout spot or a stop after a late-night swim in the pool. Hostel Block A essentially was a distrito for vegetarians, serious, God-fearing, and super straight colleagues. It had a good vegetarian mess hall that we could join. In the second year of medical school, noticing the inadequate support for the vegetarian meals, I tasted the readily available meat gravy and soon converted to be a non-vegetarian.

The new Hostel "C" Block was a double story, modern building with single rooms, a large vestibule, dining hall, and common room (Fig. #45,46). During my time, it was well-maintained and a star attraction of the medical school. It was very well maintained with fresh coats of paints and sparkling window pans.

Boys Hostel C Block, The lobby, 1, The dining hall, large tables with shattered chairs, 2, Common room. lack of adequate furniture,3, Common room with shattered window pans, 4, Outside view, 5.

Alas, like the rest of the medical school, this has also turned into a "live in ghetto" - a slum! Total lack of maintenance, apathy, and perhaps lack of resources are the contributory factors. More likely, it is the corrupt leadership that turns a blind eye to the reality and pockets the funds. Recently, a national newspaper ran an article detailing the dismal sanitation and lack of basic amenities. The dining room has broken tables and cockroaches\; the common room has little furniture, a non-functioning radio, and missing window tiled at all corners with leaking water pipes and sewage overflowing behind the rooms.

Hostel C Block. Common room window (A), My room #19 (B), Filthy court yard (C), Exposed electric wires (D)

Medical School Education

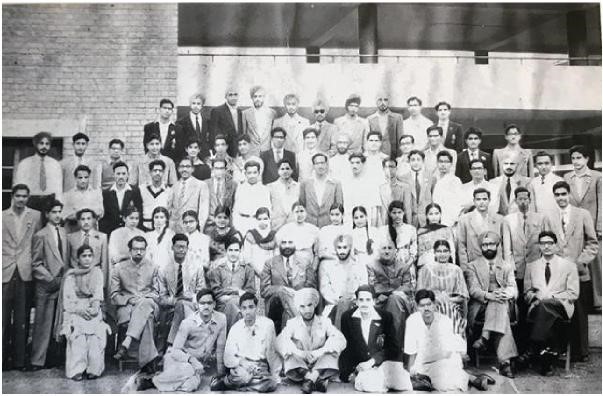

Fifty of us matriculated to enter the class of 1955 for MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery), US MD equivalent degree. My colleagues were mostly from the Punjab and the neighboring states of Himachal Pradesh, Utter Pradesh, and Delhi. There were three nominees of the central government from neighboring countries and an additional five from the Union Territories, and the State of Jammu and Kashmir. Additionally, we had some colleagues held back from the previous year.

Class of 1955 Bottom: L-R. Ramesh, Raj, Gurcharan, Tara, Amer. 1st Row: Jaswant, Ashok, ?, Satinder, Ishwer Singh, Teja,?, Chanchal, Kharag Singh, Dr. Khanna.2nd Row: Dalip, Suri, Batra, Brij mala, Shobha, Kamlash, Indira, Urmil, Tirlochan, Saroj, Mohini, Jasbir, Raminder, Perbodh, Bhag Chand, Bhim Sen. 3rd Row: Bhagwan, Sher Singh, Maini, Kishan Mohan, J Chawala, JMangla, Loomba, Prem Avtar, SM Sharma, Budhiraja, Vinod, Suraj, Bachna, Balbir, Hamani, Bal Kishan. 4th Row: Harjeet, Singla, Ranjit, Moti, Ravi, Amualya, Kishan, Amrit, Pasricha, Birbal, Virender, Prabodh, Bal, Ashwani. 5th Row: Ravi, Rajinder, Maharban, Nakai, Harbans, Gurdeep, Manmohan, Dhinsa, Surinder, Kamal. Missing: Arjumand Mahmud, Balbir Cheema, Gopal Krishan, Jaswant, Jatinder Kalia, JKsharma, Joginder Singh, OP Dutt, Punjab, Ranbir Singh, Sudhir, SN Sethi, Swaraksha Ohri, Vijay Kocher.

Admission to the medical school was merit-based and included an interview, psychological testing, and a physical examination. There were over 5,000 students taking the premedical courses, and an extremely select group of the super smart and academically accomplished candidates were accepted into the medical school professional program. We were not only from different states but also represented much social and cultural diversity. Some of my classmates had attended British-styled boarding schools, while others graduated from government run public institutions with limited exposure to the Western cultural, sports, recreations, and personalities. They were generally shy, insecure, and often felt intimidated and inferior. Most of them grouped together for meals, social activities, and after hour studying.

Our lecture halls were theater-style with a front entrance and a back door that was often utilized to slip out from another not so good lecture. Lecture halls had only a few ceiling fans. One England returned physiology professor, Dr. SK Lal, insisted on not using the fans until the middle of May, the hottest part of summer. While delivering his lectures he himself wore beige cotton three-piece suits with matching oxfords and ties. These lectures were postprandial at 1:30 pm and delivered in the shirt-drenched, hottest (temperature over 100° F) part of the day. It all ended when one of our class-fellows (Tirlochan) fainted due to heat exhaustion

During the lectures, the professors used large (4x4) glass slides and epidiascopes for illustration. Most of the learning was on the British pattern of reading, retaining, and regurgitating the facts. All the Professors were British educated and trained. The anatomy constituted the "core" of medical school education. The dissection hall always smelled of rotten meat and formalin fumes.

Anatomy dissection hall, 2005 (1). The dissection table with the cadavers covered with formalin-soaked drape cloths (2). The steel tables that we dissected on in the year 1955-56 are still in use with poor maintenance and sanitation. The table, draped body foreground was mine 50 years earlier.

I was a small fish among the sharks derived from all over the Punjab State and other parts of the country\; my classmates were toppers and represented crème-de-crème of the youths. They were smart, intense, and focused. However, the teaching was another matter. Almost all the professors had a tyrannical attitude. The year one and two were the hardest and decisive. We studied anatomy and physiology in the four semesters. Also, there was minimal exposure to biochemistry. Dr. Inderjit Diwan had a Ph.D. from London and ran the Anatomy Department, in my experience, as an autocrat. I never saw him smile\; he had a most splenetic personality. Inderjit carried a vendetta if you socialized with girls or participated in team sports. It was extremely difficult to weather the hormonal storms when surrounded by emotional pollutants and toxins. In one of our psychiatry talks by Dr. Nakai, one of us asked: "how to hook a girl." "Become a good hook," was the curt answer. We should concentrate on studies and use transformation and sublimation techniques. What a life, a life of intense emotional pollution, and no avenues of help or support!

Drs. PN Chuttani (Lt), Inderjit Diwan (Rt). Dr Chuttani was chief of medicine and an excellent neurologist. Dr Diwan chief of anatomy was harsh, controversial but had developed one of the finest anatomy department in the country (C). These teachers, among others, created strong academic foundations and teflon personalities in all of us. Photo credit: Shobha Sehgal, Chandigarh.

Probing my memories, I recall that most of the demonstrators (instructors) were coldhearted\; they were quick with verbal Tasers and BB shots! They occasionally provided a spoonful of hope and encouragement. We dissected the cadavers and their various body parts (arm, leg, head and neck, thorax, abdomen, and the brain) in stages. There was ample supply of dead bodies, mostly from Indo-Pakistan encounters and bodies of the destitute and homeless dying of infections and natural causes. Flashback to over sixty years ago, I still see the perfectly sculptured pair of virginal breasts in a teenager shot dead across the border. It sprouted the thoughts of necrophilia. After the completion of an assigned dissection stage as per The Cunningham Dissection Manuals (Oxford Press), we would have a weekly oral examination before being permitted to proceed with the next stage of dissection. Depending upon the body part, there were seven to fourteen stages for each of the assigned dissections.

There was a lot of emphasis on the human skeleton, bones, their surface markings, and attachments. I was a lucky one who passed all stages in the first try. The course required reading repeatedly, cover-to-cover, Gray's Anatomy, Hamilton and Boyd Embryology (Dr. Diwan had worked with the authors), Ranson and Clark Neuroanatomy, and Lee McGregor's Applied Surgical Anatomy. There were droplets of disdain and occasional showers in the dissection hall and classrooms. We breathed, smelled, and dreamed of Anatomy. Anatomy, anatomy, anatomy was the wall-to-wall carpet in our souls!

I remember there was a question in the annual year one anatomy examination about causes of congenital malformations. In a study published by Crag from Australia and quoted in the Hamilton and Boyd Embryology book, there was a mention of rubella infection leading to heart malformations and some other anomalies. In my answer book, I wrote additionally about radiation, some medicines, and infections leading to similar after effects. Dr. Diwan asked the whole class "who had written such unproven, imaginative, and crazy things." He was visibly mad. None of us, including myself, had the nerve to stand up and acknowledge it. All these and many more are now recognized as contributing factors to the congenital birth defects. To me, this was a most logical but poorly documented thought in the 1950s.

Samson Wright's Applied Physiology, an over 1,000-page tome, was the required text for the physiology course. Subjects were hard and made much worse by the insensitive, patronizing faculty and lack of guidance and emotional support. Reading about vitamins, we all felt sick and embarked on daily multivitamin pills. Physiology labs were mostly unstructured and jokes. The activities included the recording of frog muscle twitches on carbon soot smoked drums, determining hemoglobin using the Hayden Hemoglobin meter, and bleeding and clotting times by nicking the earlobes of the classmates

At the end of year one, there was an annual examination in anatomy and physiology. If you failed in one of the two subjects, you could retake the exam in six months and continue studies with the next class. However, if you failed the second time, you lost a year. The second-year examination finals were a real game changer. Students were sacked out of the medical school if you did not pass the finals on the second attempt. It was dreadful that each year four or five colleagues who had been chosen based on academic performance and excellence were asked to leave the medical school at the end of the second year, all flunking the anatomy examination. It is still shocking that some of the brightest young students were considered unfit to pursue further medical education.

Parenthetically, in the US, this is considered a failure of the teachers and not the students. Examinations in the subsequent years were not much different except one was not forced to leave the medical school. The final year examination was the most challenging with patients and POC (point-of-care) performance evaluations. We were nearly sixty-five students in the final year (some had been held back from the previous years). I think during the five years of the formal education, only eight of us could pass all of their examinations in the first attempts\; I was one of the lucky ones.

During the summer months, we often draped ourselves in moist bed sheets to stay cool while studying. Most of my class fellows formed study groups and read together to find intellectual solidarity, often staying awake late at night. A tacit system of bragging rights among us over who studied late was practiced. I was amongst a few who studied alone. Also, I read most of the textbooks cover to cover rather than cherry picking and learning only that which was considered "important".

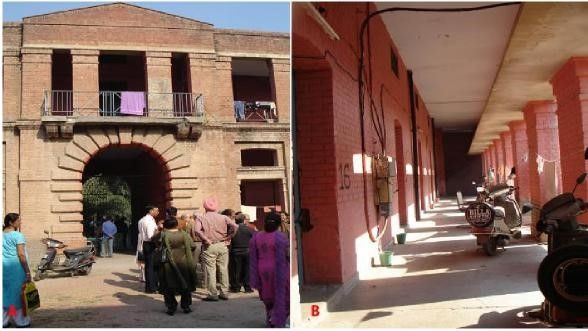

Although not very wise, this sealed my fate in Pathology. It so happened that the examiners now included American professors from Christian Medical College, Ludhiana. They had tossed in two unexpected alien questions in the final Pathology examination, (i) liver changes in yellow fever, a mosquito-borne infection not seen in India and (ii) diagnostic value of a peripheral blood smear. The answers required a wide coverage of the various topics in the book and mobilizing numerous unrelated threads to be woven into a diagnostic, meaningful tapestry. It just happened that I performed exceptionally well in Pathology. Clinical training essentially took place at the VJ (Victoria Jubilee) Hospital, which was about three miles away, and a twenty-minute bicycle ride (Fig. #49). After the 8:00 am classes, we would cycle to the hospital for the 9:30 am clinical sessions. This hospital was an old complex of brick buildings named in commemoration of the Silver jubilee celebration of Queen Victoria.

VJ (Victoria Jubilee) hospital (A), Entrance (B), The 124-year-old hospital building (C, Current use Heritage Festivals (D).

The buildings had inpatient wards and outpatient facilities. Various buildings were separated from each other by bush and tree-lined walks and roads. There was no vehicular traffic permitted inside the hospital. At each end of wards with forty beds arranged in two parallel rows of beds were two air-conditioned rooms for selected sick patients. In the last three years of medical school education, we would attend the outpatient clinics and indoor ward rounds with the senior attending staff members including Professors Ram Prakash Malhotra, Yudhvir Sachdeva, Santokh Singh Anand, and others.

After finishing the morning rounds in the male ward, we would form a procession around the "chief" while moving on the streets behind them and walking toward the female ward. Invariably there would be another "Chief" (Professor PN Chuttani) coming from the opposite side of the street with his entourage of students and house officers and there would be an exchange as to who had the larger following and crowd? I felt that the whole academic atmosphere was venomous, and a large proportion of learning was more contacts and less content-based. There were, just to name a few, real gems, caring, compassionate and loving faculty members including Drs. Waryam Singh (Surgery), Ranbir Singh (Ophthalmology), Ishwar Singh (Physiology), Clara Phillips (Ob/Gyn), and Vidyasagar (Mental Health). They also provided mentorship and guidance. Dr. SS Manchenda was Chief of Pediatrics, a very fine teacher, and a jovial person, we had fun in his classes.

Registrars (Chief Residents) had their own evening rounds. They would share some pearls of wisdom, practical tips, and whims of the professors. These clinical rounds, although not mandatory, were useful and well-attended. Unlike the professorial morning rounds, where your presence was carefully noticed (you were expected to drop all activities to be visible and counted), these exercises were more relaxing and informal. Often times, we prepared a case and presented it to the group, an excellent learning experience, In the bedside training, much emphasis was placed on the clinical sciences rather than the investigational studies.

In my opinion this one, most valuable British system of medicine teaching remains unparalleled in the outpatient general medicine and general surgery clinics, we presented cases to the professor in the presence of colleagues and some patients and their attendants. Several senior staff members were most condescending and indulged in public strip downs. Many of their comments were rapacious and humiliating. It was what I considered demeaning and subhuman behavior. Rotations in other clinical specialties, including the Obstetrics and Gynecology, the Ear Nose and Throat, the Dermatology, Radiology, and Ophthalmology, were generally more relaxing and enjoyable. I remember when the eye surgeon knifed the cornea for cataract surgery, and I fainted. Delivering babies at odd hours required our stay on the hospital campus. Dr. Vidyasagar, a highly respected icon in the field, taught psychiatry. It was interesting that the course and self-analysis often produced scary and depressing feelings.

The course contents in the various areas were mostly imbalanced and often depended upon the seniority and the clout of the professor. Internal Medicine was nearly 40% cardiology. Although Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine was the "baby medicine" text, most of us ended up reading "Price's Textbook of the Practice of Medicine" an over 1,200-page tome. The text was read and reread many times and highlighted by colored pencils, there were no yellow highlighters in those days. I think over half of the intercellular space in the cortical tissue was infiltrated with internal medicine, mostly cardiology. We had nearly forty lectures in dermatology alone. Also, we had six lectures in dental and oral medicine. We were only interested in knowing which toothpaste to use and should I use a soft or a hard toothbrush? Most professors had private chambers where they examined well-to-do patients for a nominal fee of Rs. 20.00 (about $5.00 at the exchange rate of those days).

We had our lighter moments in the clinics sometimes. I remember one morning Professor Chuttani, a neurologist, was demonstrating retropulsion in a patient suspected of Parkinson's Disease. (In this test, once pushed forward, the patient is unable to stay in that position and recoils back). After a few displays of the test, the patient turned to Professor Chuttani and said, "You mother fucker, you keep pushing me all the time and do not give any medicine." In our surgery clinic, we were asked to examine a fourteen-year-old boy with an inguinal hernia. After a few of us had done our examination, one rather attractive female colleague (Shoba) had the back of her hand wet with pre-ejaculate. Of course, the boy was quickly covered with a sheet and removed from the clinic.

Dr. S. S. Manchenda was the Chief of Pediatrics. One morning, he was demonstrating a baby with a red buttock- perianal pruritus that occurs due to high sugar consumption and resultant yeast infection between the moist gluteal folds. One of our sharper colleagues (Harbans) came up with the thought that the rear ends (buttocks) of monkeys are red because they chew too many sugarcanes. This note, scribbled in Urdu on a small piece of paper with the contraband thoughts, was shared one by one across the clinic resulting in waves of giggles and amusement. In India, sugarcanes are transported in open rail cars and have monkeys chewing them while riding the train cars. As we all know, the primate rear end redness is due to sexual excitement and not by eating sugarcanes. We were all frazzled reading and memorizing the "facts."

Oral examinations were extremely stress-filled. Dr. Malhotra, Chief of Cardiology and Medicine, was conducting the oral examination of our group. Tirlochan Bhatia, one of my colleagues, was extremely nervous and stated, "I read everything but have forgotten most of it." Dr. Malhotra, in a lighter vein, asked her what she remembered, "Heart Sir," was the curt response. "Okay Tirlochan, "what is heartburn" was the question asked. We had a good laugh\; heartburn is due to hyperacidity in the stomach. Another time, one of the class fellows was told, "Okay, you just passed pathology, what do you find in the heart of a patient with mitral stenosis (narrowing of the heart valve with fusion of the valve leaves)?" "Dyspnea (shortness of breath), Sir," was the bullet fired in response.

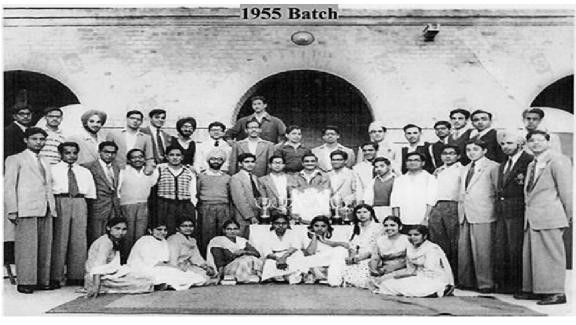

Our class excelled in sports, and the annual week of sports was a gala affair with much fun and relaxation (Figs. #50, 51). We had annual sports, intercollege tennis, and swimming meets and sports exchanges with the medical students in Lahore, Pakistan. I accompanied our cricket team for a match with the KE Medical School players to Lahore. The West Indies cricket team stayed in our dormitories\; we rubbed shoulders with the players and became quite friendly with the world-class cricketers. Holi was one of the few fun-filled social activities in the school when we all were in the town. We all played with dry color powders. The highlight of the festivities was the consumption of bung (Marijuana) in a milk-based cold drink (Thandai) or as deep-fried paroraks (fritters) in the end. There was much noise and dancing in front of the girl's hostel with newspapers spreading the middle of the tarred road.

Class of 1955 with the Medical School Sports Trophy.

Annual sports party(A), notice single woman Urmil Manchenda on the table (B).

I also saw cases of smallpox and diphtheria. There was an infectious disease hospital and rotation was required as a part of infectious diseases and preventive medicine rotations. Patients with smallpox would develop pus-filled nodules on the body, and they would leave deep scars on the skin for the rest of the life. Fortunately, in the year 1979, (WHO) the World Health Organization, Geneva declared the world smallpox-free. Today, there are only two sources of the live virus stored in the world, CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), Atlanta and a lab called "Vector" in a remote area of a Siberian town in Russia. Rare faces with healed smallpox scars can still be seen among people who are in their seventies or older, more so in the developing countries. This smallpox elimination was a major feat.

For the first time, reflected a global initiative by the WHO, spearheaded by a team led by Dr. Doland Henderson with experience in operational research from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore. Healthcare workers vaccinated most of the children attending schools against smallpox in the school. However, the infection persisted in the villages and among the small, closed communities and religious groups who opposed vaccinations. Perhaps they should consider keeping an image of a small pox case in a place such as Madame Tussauds Wax museum in London. Tuberculosis was another rampant disease, and almost all of us had exposure with resultant positive PPD (Purified Protein Derivative) tests.

Verka (The Village/Block Posting)

After graduation, we were required to undertake a six-month internship at a village posting. Verka is a small block that includes fifty-two villages and is about eight miles from the medical school. It had an old, palatial building that was used as our residential space. There was a kitchen, outpatient facilities, and a small cottage for the chief. The atmosphere was friendly and included social workers, nurses, and paramedics with ambulances and transportation facilities. The ambulances and transportations were utilized to transfer really sick patients, visits to the villages, and other health centers, as well as bringing in supplies and food for meals from the town.

Verka village posting.

We visited the airport to study the quarantine procedures and the villages for house calls, physical examinations, and provide clinical care (Fig. #53). This was an excellent opportunity to hone our clinical skills and put our newly acquired knowledge to test in the real world. It was a good break from the grueling studies of the final year of the medical school.

Airport visit for quarantine and Dakota plane for emergency and safety training

Occasionally, we traveled to the inner villages performing basic tests and distributing iron tablets to the pregnant women. I had also acquired a Rollicord V camera from Subodh that he had purchased in the US. It was one of the finest cameras available in the world, and I learned the basics of photography during my internship. I took pictures at every opportunity and became the unofficial photographer of the class. Almost all the black and white pictures in this book were shot by me using this camera.

RolleiCord V (circa1950s), my first camera with the leather case still resting on my shelf.

I did get into some trouble with some of my colleagues when I was alleged to have snapped some unflattering shots. I also documented many clinical cases during my residency, but those images remain printed only on my cortical and not the cellulose paper.

Graduation

Following the completion of our internship in December 1960, we went to Chandigarh in the winter month of January 1961 and received our Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, MD US equivalent) degrees in a convocation at the Punjab University main campus for ceremonies under an unheated tent. This is the new capital of Punjab state\; the French architect Lee Corbusier designed the city. It is a very modern and lovely place to visit. The streets are wide, with well-appointed crossings, greenery, and pedestrian walks. There is plenty of open space providing fresh air to the residents. The city is the seat of two state capitals, Punjab and Haryana. It has a world-class PGIEMR Post-Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research) similar to the AIIMS in New Delhi.

Many attractions in the city include the world-famous Rock Garden, created by one Mr. Nek Chand in the year 1957. It now covers over forty acres of stone-made sculptures, rocks, and recycled materials. Mr. Nek Chand died recently, and the fate of the creation is uncertain now. Alas, like any other metro area in India, the dream city of Mr. Lee Corbusier has lost its distinctive character. I am told all this has changed in recent years, a victim of population growth, politics, and corruption

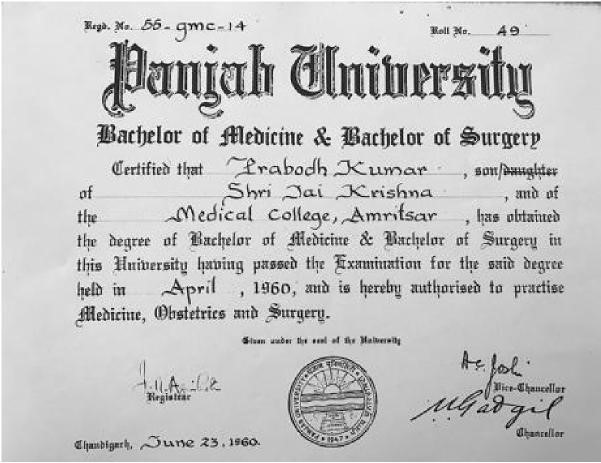

I purchased my first wool suit for the occasion. I did not have my last name on the printed diploma document. In India, the caste system did and still does matter in life. One's last name identified the caste and was not used by our family to avoid discrimination and social recognition.

MBBS Diploma. Notice the missing "Gupta" in the document. In those days it included father's name also.

In the year 2005 we met for our 50th class reunion and I visited the Medical School. Tears rolled down from my eyes, and I cried seeing the dismal state of the facilities. The most beautiful anatomy museum is all ruined with broken jars and dried-up specimens as if run over by a bull in a china shop and the place left to disintegrate and decay. I felt tremendous pain and sympathy for the young, bright doctors-to-be students for the abysmal academic environment they were living through.

Class reunion 2005. L-R. Bhim Sen, Balbir Singh, Batra, Sher Singh, Ashwani Kumar, Kalia, Perbodh Sager, Tirlochan, Raj Goyal, Harbans Singh, Mohini Malhotra, Nakai, Narang, Tara Chand, Jasbir Kaur, Ravi Kapur, and Prabodh

During an informal talk to a group of the current medical students, I told them, "You are so bright that I could not enter the medical school now competing with you all. If you do not reach far in your lives, blame the road you are driving on and not yourself\; you have a V-8 engine able to cruise at the maximum speed and full throttle." I am appalled at the total lack of commitment, concern, and sensitivity among the people in power. That place, its culture, the history and the intellect, have so much potential to contribute to society, but it is wasted. Wonder if I can help improve the conditions in any way? I am surprised and admire the passion and commitment of the students who are able to perform so well and turn out to be world class physicians.

I was among a few of the graduates who were not interested in staying in Amritsar for the residency training\; the atmosphere was hostile and emotionally lethal. There were, however, a few friends staying behind at the base camp. Some of us were more extroverts, adventurous, and mostly from the Delhi area. We decided to move to Delhi for the residency and house job placements. Irwin, Safdarjung, and the Willington Hospitals were the most sought out places for residency training at that time. Kalawati Saran was an outstanding pediatrics facility affiliated with the Lady Hardinge Medical School. I applied for residency training in internal medicine at the Irwin Hospital and was accepted.

______________________________________

© Prabodh Gupta 2019

Comments

Add new comment