Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

USHA RANI: A very personal memoir

Category:

Khushwant Singh was an Indian author, lawyer, diplomat, journalist and politician. His experience in the 1947 Partition of India inspired him to write Train to Pakistan in 1956 (made into a film in 1998), which became his most well-known novel.

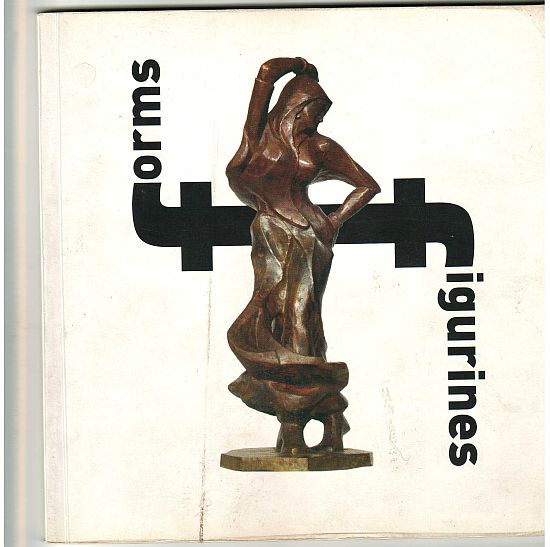

Editor's note: Rakshat Hooja, Usha Rani's grandson, has provided this material. The memoir was given by Khushwant Singh to the Hooja family, and was originally included in the private and limited circulation only booklet forms and figurines. The booklet was printed in 2005.

Cover page

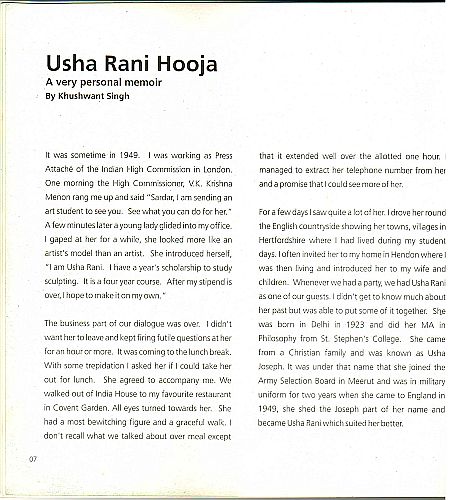

It was sometime in 1949. I was working as Press Attaché of the Indian High Commission in London. One morning the High Commissioner, VK Krishna Menon rang me up and said "Sardar, I am sending an art student to see you. See what you can do for her." A few minutes later a younger lady glided in to my office. I gaped at her for a while, she looked more like an artist's model than an artist. She introduced herself "I am Usha Rani, I have a year's scholarship to study sculpting. It is a four year course. After my stipend is over, I hope to make it on my own."

The business part of our dialogue was over. I didn't want her to leave and kept firing futile questions at her for an hour or more. It was coming to the lunch break. With some trepidation I asked her if I could take her out for lunch. She agreed to accompany me. We walked out of India House to my favourite restaurant in Covent Garden. All eyes turned towards her. She had a most bewitching figure and a graceful walk. I don't recall what talked about over meal except that it extended well over the allotted one hour. I managed to extract her telephone number from her and promise that I could see more of her.

For a few days I saw quite a lot of her. I drove her round the English countryside showing her towns, villages in Hertfordshire where I had lived during my student days. I often invited her to my home in Hendon where I was then living and introduced her to my wife and children. Whenever we had a party, we had Usha Rani as one of our guests. I didn't get to know much about her past but was able to put some of it together. She was born in Delhi in 1923 and did her MA in Philosophy from St. Stephen's College. She came from a Christian family and was known as Usha Joseph. It was under that name that she joined the Army Selection Board in Meerut and was in military uniform for two years. When she came to England in 1949, she shed the Joseph part of her name and became Usha Rani, which suited her better.

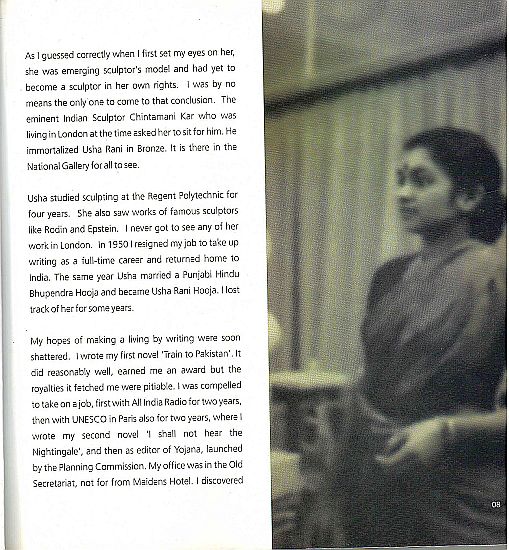

As I guessed correctly when I first set my eyes on her, she was an emerging sculptor's model and had yet to become a sculptor in her owPn rights. I was by no means the only one to come to that conclusion. The eminent Indian Sculptor Chintamani Kar who was living in London at the time asked her to sit for him. He immortalized Usha Rani in Bronze. It is there in the National Gallery for all to see.

Bronze portrait bust of Usha Rani by Chintamani Kar. Circa 1949.

Usha studied sculpting at the Regent Polytechnic for four years. She also saw works of famous sculptors like Rodin and Epstein. I never got to see any of her work in London. In 1950 I resigned my job to take up writing as a full-time career and returned home to India. The same year Usha married a Punjabi Hindu Bhupendra Hooja and became Usha Rani Hooja. I lost track of her for some years.

My hopes of making a living by writing were soon shattered. I wrote my first novel "Train to Pakistan". It did reasonably well, earned me an award but the royalties it fetched me were pitiable. I was compelled to take on a job, first with All India Radio for two years, then with UNESCO in Paris also for two years, where I wrote my second novel "I shall not hear the Nightingale", and then as editor of Yojana, launched by the Planning Commission. My office was in the Old Secretariat, not for from Maidens Hotel.

I discovered to my joy that the Hoojas were living in a flat close by. I made it a habit to drop in on them at lunch time. Bhoopee, as I called him, was into Hindi literature as well as preparing to sit for the IAS exam. I had yet to see any of Usha's sculptures.

A longer break was in the offing. I got a Rockefeller Grant to work on the history of the Sikhs. I resigned my government job to gather material in the National Archives and work in my father's house. Bhoopee made it to the IAS and chose to serve in Rajasthan were his brother was already serving. I went abroad looking for material on the Sikh diaspora. And when I had written my two volumes on Sikh History published by Princeton and the Oxford University Press, I took up the editorship of "The illustrated Weekly of India" in Bombay. I was there for nine years before I was sacked and returned to Delhi to take up the editorship of "The National Herald and then "New Delhi" magazine. I lost contact with the Hoojas and still had not seen Usha's work.

An assignment for "New Delhi" to interview Shraddha Mata, then living in Jaipur, took me to the town where the Hoojas lived. According to M.O. Mathai, Shraddha Mata had borne Pundit Nehru an illegitimate child. I had met her earlier in Nigambodh Ghat, Delhi's main cremation ground where she was living in a tent erected amongst burning corpses. She was tantric. We hit it off very well. She had invited me to Jaipur, where the Maharaja had gifted her an ancient fortress atop a hill. She occupied the tower of Hathroi Fort and the rest was inhabited by black pigs, dogs and cobras. I had taken my photographer with me. But uppermost in my mind was to re-establish contact with the Hoojas.

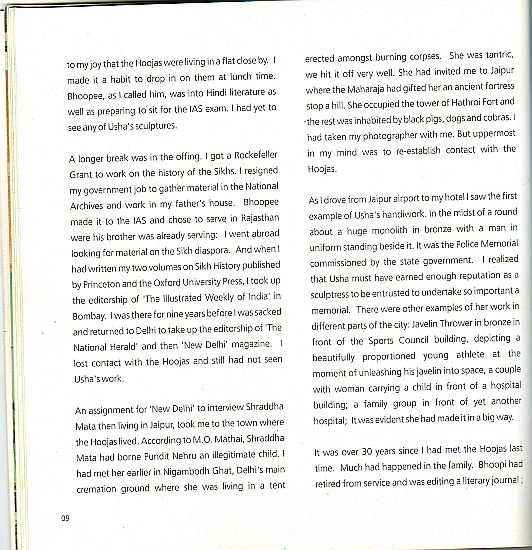

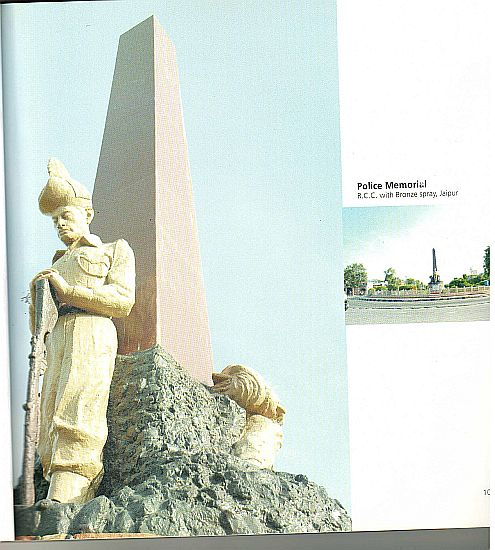

As I drove from Jaipur airport to my hotel I saw the first example of Usha's handwork in the midst of a roundabout, a huge monolith in bronze with a main in uniform standing beside it. It was the Police Memorial commissioned by the state government.

Police Memorial, Jaipur. Photo in original booklet.

I realized that Usha must have earned enough reputation as a sculptress to be to be entrusted to undertake so important a memorial. There was other examples of her work in different part of the city\; javelin thrower in bronze in front of the sport council building, depicting a beautifully proportioned young athlete at the movement of unleashing javelin into space, a couple with women carrying a child in front of SMS hospital building\; a family group in front of yet another hospital\; it was evident she had made it in a big way.

It was 30 years since I had met the Hooja's last time, much had happened in the family, Bhoopee had retired from service and was editing a literary journal\; their son Rakesh had made in to the IAS and married a girl in the same service. Their daughter Rima had won a scholarship to Cambridge University. Soon as I got to my hotel, before ringing up Shraddha Mata for an appointment, I rang up the Hooja's number, I was invited over to spend the evening with them and stay on for dinner. Their home in Uniara Gardens was a modest sized cottage with a small gardens patch in the front and rear and a longish garage which Usha used as her studio. As I expected it was crammed with books and artifacts, many of them molded by Usha, some replicas of her work now in Indian and foreign art galleries and in private homes. It was a literary-artistic set up.

I received a warm welcome. Though Bhoopee showed his age, Usha despite strands of grey hair looked exactly the same as she did the day she first walked in to my office in the London. We reminisced about our past days. Through the window I could see a peacock and two hens strutting about in the garden like domestic fowl. I expressed surprise that they could be so intimate in the human surroundings. Rima who happened to be there on vacation said\; "uncle you want to see some fun?" Without waiting my answer, she went out to the roof. From there she made the trumped call of a peacock. Her invitation was perfect\; peacocks from the neighbourhood replied to her call. It was a never-to-be forgotten experience. As I was leaving they asked me what had brought me to Jaipur. I told them. "Take me along" said Usha, "I have heard about her but never met her."

Next morning I picked up Usha and drove to Hathroi fort. On the way I bought a basketful of fruit to present to Shraddha Mata. We pulled up at the foot of the escarpment\; went through a scramble of hut of Harijans, though the inlet in the massive gates of the fortress and up the stairs to the ramparts which she had converted in to her residence. Shraddha Mata was seated in a chair with a couple of male disciples standing beside her. I placed the basket of fruit before her and touched her feet "Too aa gayaa" she said by way of greeting. By then she had acquired a vocabulary to cut me down to size calling me a ghamandi (arrogant) who thought no end of himself. "Apney aap ko bahut samajhta hai" she said with affection. Before I could introduce Usha, she asked "Ye Chhokree kahaan se laaya hai" (where did you pick this girl).

Usha was a grandmother in her sixties. Being described as a Chhokree only confirmed my belief that she was ageless. We spent an hour with Shraddha Mata. While she talked to me her eyes were fixed suspiciously on Usha. This was the last time I saw Shraddha Mata. She died some months later. She was highly diabetic and was cremated in Hatrohi Fort. I was robbed of an excuse to visit Jaipur.

However, I did visit Jaipur a few times at the invitations of the University, Jaipur Rotary and the Rajmata Gayatri Devi. And on every visit I made it a point to call on the Hoojas. Usha had begun to pick up a mild fever in the afternoons but continued working in her Studio. I saw some more of her work. I was specially struck by two: here wire rendering of the stallion Chetak, Rana Pratap's horse as it was about to take off for the skies. It had the same mobility as her Javelin thrower. And The Kiss, more tender and intimate than Rodin's masterpiece of which I have a miniature bronze replica in my sitting room.

The Kiss. Sculpture made by Usha Rani.

The rest of her work I have only seen in pictures in brochures of the exhibitions she has had in different cities.

My last visit to Jaipur was as a guest speaker at the annual function of Maharani Gayatri Devi School. As soon as I reached the city, I rang up the Hoojas, someone in the family had met with an accident. They were unable to attend the school function (she was on the governing body), nor the dinner hosted for me by the Rajmata. Nor invite me to their home. I never went to Jaipur again.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Some Usha Rani photos.

Usha Rani with her son Rakesh Hooja. 1952. London.>\;

Usha Rani working in her studio in Delhi. 1956.

Usha Rani in Jaipur. 1970s

Usha Rani in Jaipur. 1970s

____________________________________________________

© Photos Rakshat Hooja 2018

Editor's note: I approve all comments written by people\; the comments must be related to the story. The purpose of the approval process is to prevent unwanted comments, inserted by software robots, which have nothing to do with the story. If the captcha puzzle below is too hard, please send you comment to indiaofthepast@gmail.com\; the editor will post it for you.

Comments

Add new comment