Discipline and Courtesy in the Services

Category:

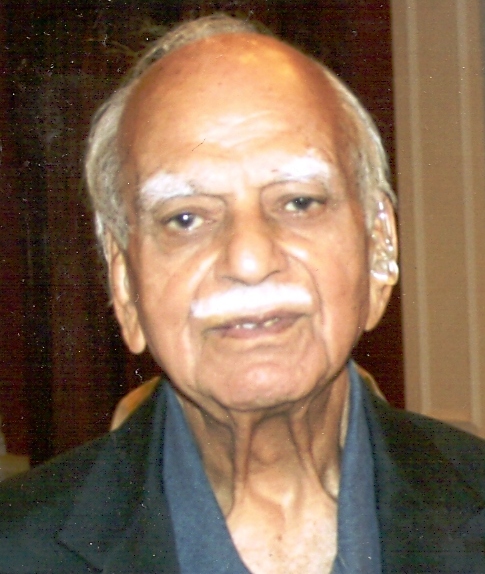

Premnath was born in 1918. He served in the Army before India became independent. Soon after Independence, he joined the Railways, where he worked for 30 years. At present he lives with his wife in Gurgaon.

I became an army officer during the Second World War when India was still under British rule. Army service was, of course, total discipline – you had to do what you were told to do.

But, what I experienced was that the man who told you what to do had traits of kindness, convictions in asking you to do what he wanted, and interacted with you in a fair and reasonable way.

After an intensive training course, I was sent to Burma (now Myanmar), which was also under British rule at that time. Here I was asked to go to the combat area to witness the service conditions - which were really tough during monsoon season in the jungles of Burma. When I returned to the base after visiting the front line areas, there was a message waiting for from my Commanding Officer to see him. I went to see him, not knowing what I was in for, but mentally prepared for any dressing down. But, he was very sweet and kind. He appreciated the effort I had put in to go round to see things on the ground, and gave me some sound words of advice.

As I was about to leave, he asked me if I had called at the local Mess, which I had not done. He explained to me that the Mess was the not only the place where all officers ate their meals together, but also the meeting ground for officers in their spare time. He said that calling at the Mess and signing in the visitors' book ensured that all visiting officers would be looked after properly at the Mess. This message was given kindly as an advice. I somehow found the courage to ask the Commanding Officer how he came to know that I had not called at the Mess. He told me that he had received a wireless message from the commanding officer of the area I had visited to inform him about it. I was very gracefully made aware of the army tradition. I had learnt a lesson never to forget, given in a manner never to resent and to establish a shared the relationship between a senior and a junior officer.

Later, I was promoted to the rank of Major not on the basis of years of service but just because I was the senior most man available to work in a field area. My first day in the higher rank started in the normal manner of "Yes, Sir" in my dealings with my regiment's Colonel, who was my superior officer. At lunch time, when I was busy with my work, my Colonel came to my office, patted me on my back, pulled me out of my seat, and took me out to the local club saying, "Let us go and wet your ‘Crown' - the shoulder badge of my new rank." Another shared relationship between a senior and junior officer.

In Burma, the British were fighting the Japanese. It was almost impossible to catch a Japanese soldier as a prisoner during the operation as it was common practice for the Japanese soldiers to kill themselves with their own weapons rather then be taken as a prisoner of war in the jungle of Burma.

Still, there were a number of Japanese prisoners of war at our base, and one of my jobs was to arrange for food supplies for the Japanese prisoners of war under our control. A Japanese officer of the rank of Major had to present his requirements to me weekly. On his first visit to office, he came in and saluted me but kept standing. I thought he was waiting for the courtesy of my asking him to sit down on the chair. But he kept standing and quite firmly said "Sir, I am a prisoner and cannot sit on a chair before you." Actually, he kept standing until he completed his job - then he saluted me and went out.

These prisoners of war were required to do physical labour of all types for which they were brought to the site of work in trucks. As prisoners, they were required to salute every British and Indian officer they happened to come across. Even while they wee standing in trucks, the Japanese soldiers would at once salute any officer whether walking or riding a vehicle passing by.

When at work, the prisoners were given deadlines for the work they had to do. My experience was that the Japanese always completed the work well within the specified time, and there was never a problem with what they had done. There was never any need to supervise the working of the prisoners.

All prisoners of war camp were guarded but there were hardly an occasion when any inmate of the camp misbehaved or did any thing unlawful or disobeyed orders. Any act of misconduct was adequately dealt with by the Japanese' own supervisory staff. Once, a group of Japanese prisoners sent to unload a boat. An Indian soldier supervising the work saw a Japanese prisoner stealing a tin of cheese. The Indian soldier took no direct action - instead he reported this to the Japanese supervisor. He immediately got all the prisoners to appear before him, searched each prisoner and recovered the tin from solider. The, the supervisor started hitting hard the offender, and had to be stopped. In his defence, the supervisor said, "Sir, he has brought a bad name to our Emperor and has to be punished for it."

When the war ended, Japanese soldiers locked up in pockets in Burmese jungles kept fighting till signed pamphlets by the Japanese king were dropped in the jungles from the air to advise them that war had ended. Immediately thereafter there was voluntary surrender of the arms by the Japanese army in the jungle pockets.

Railway life

On leaving the army, I joined the Railways and had to undergo training in various phases. I got married during the training period. My relatives in Bombay wanted my wife and me to spend some holidays with them. Since each training phase was for a short period, my absence for even for a week would be a serious interruption. So, I hesitated to ask my supervisor for leave. However, on persistent demand from my brothers and sisters, I mustered up my courage to ask for a week's leave. I was quite prepared for my request to be denied - and ready even for the likely scolding for making such a request.

As expected, my supervisor asked me to meet him. In our meeting he offered me a cup of tea and made me feel at ease. He discussed my progress in training, gave me few useful tips - and asked me to tell him I would do during my leave. When I told him that that I proposed to go to Bombay from Calcutta to spend some time with my family after my wedding, he remarked that one week would be too short for this purpose. I almost got disappointed as I took this remark as a prelude to refusing me leave, but he followed it up with a pleasant surprise that I could go for two weeks! With a gentle smile, he said he was sure that I would put in an extra effort to complete my training on my return.

This gave me a great sense of responsibility a trainee. I also learnt a great lesson in how to deal with my juniors in the future. Many years later, when I was a senior office in a similar situation, I remembered this lesson, and dealt similarly with a junior office.

At this time, my parents had been dislocated from Pakistan, and were living in Delhi with unsettled conditions. I was posted far away at Calcutta, and it was difficult for me to look after them from there. When one of the Railway's senior officers visited Calcutta, he asked me if I had any problems for which I needed help. Boldly, I asked him whether I could be posted near Delhi, so that I could look after my parents. He gave me a sympathetic hearing but made no promise except that he would bear it in mind. Two months later, he called me and asked me if I would like to be posted at Allahabad from where I could visit Delhi on official work. I accepted. It was a great gesture that not only helped me at that time but also prepared me for my future role as a senior officer.

During my stay at Allahabad, we celebrated Holi. When other officers visited my house to play Holi with me and my wife, we served some snacks and drinks to all senior officers and their families and had a merry time. Very quietly I took some drinks and snacks to the drivers of cars of the visiting officers and rejoined the crowd of officers playing Holi. My boss, the Divisional Superintendant - had noticed my gesture. Quietly, he came to me, patted me on my back and said, "Well Done, My Boy!"

In those days, it was customary that a newly posted officer made a social call at the boss's home. Unfortunately, as a newly married couple, somehow my wife and I did not find the time to do so right away. Just when we were planning to do so, one evening when we returned home, we found that my Divisional Superintendant had called at our residence. In our absence, he had left his visiting card.

Next morning I went to his office to apologize to him for our failure to call at his home, and thanked him for calling at our place instead. He stood up, shook hands with me, and very sweetly said, "I just wanted to know how the young couple was doing." Again a wonderful gesture and a lesson learnt in how to deal with your juniors.

During my work for the Railways, at one time I had a grievance that I had been denied a due promotion. When one of the General Manager's came to visit, I asked for an opportunity to make my case to him. I expected to be called to see him and was feeling disappointed when I was not called. Suddenly, my office door opened, and the General Manager walked in, accompanied by other senior officers. I was spellbound! I never expected that all these senior officers will come to my room to talk to me. Once I had greeted them, the General Manager told me that he had taken note of my grievance. He asked me to trust him, and assured me that I would get my due promotion at an appropriate time. The whole matter was handled so pleasantly.

Much later, I had an unpleasant experience of political interference - an unhappy trend that was gaining ground in the Railways. I had dismissed a vending contractor for the poor service he was providing, despite repeated warnings and opportunities given to him to improve his performance. The contractor approached the Minister for Railways through an important Member of Parliament, and accused me of demanding a bribe! The Minister wanted severe action to be taken against me immediately. Fortunately, my boss met the Minister and told him that I had a clean reputation, and that the contractor's complaint should be handled in the normal administrative manner. In the end, the complaint against me was dropped, and my action was upheld.

Looking back, I feel that in my youthful days, official life was more disciplined than it is now. And the way in which confidence and loyalty was built between seniors and juniors in the service - that also seems to have been lost.

© Premnath 2009

Comments

Add new comment