Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

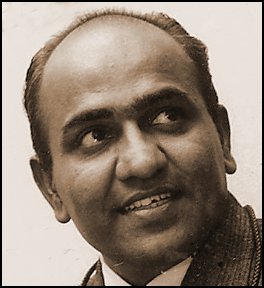

Taking a Photo of Sri Chandrasekarendra Saraswati by T.S. Nagarajan

Category:

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

(Editor’s note: This article originally appeared on http://churumuri.wordpress.com/ and is reproduced here with the author’s permission. The incident narrated in this article took place on February 2, 1975.)

As a photojournalist, I have had many opportunities to meet with the rich, the famous and the divine. But one of them stands apart as a great experience: my encounter with Sri Chandrasekarendra Saraswati, the late Paramacharya of Kanchi Kamakoti Peetam.

The swamiji was known for his utter simplicity and austerity even during his active years. Rarely did he travel in a palanquin. He was content to walk from village to village in the manner of the sages of yore. Wherever he went, people swarmed round him. His very glimpse sanctified the devotees. To hear his discourses of profound simplicity was considered a rare experience.

When I went to Kancheepuram, the sage had left the mutth and was living in seclusion on the outskirts of the town in a small hut with mud walls and a thatched roof. The swamiji’s room had a window which opened for him the world he wanted to renounce.

I went near the window and saw the sage, a wisp of a man, staff in hand, squatting on the floor. His head moved quickly, this way and that and his tired eyes looked at me. They were without expression.

I bowed and closed my eyes with the picture of the shrunken saint captured in my mind.

When I opened my eyes. I found the sage still focusing his vision towards me. Then he looked away.

It was a day of silence for the swamiji. He lived in the hut with a few helpers from the mutth in a world of his own. He gave no discourses but preferred to immerse his profundity in silence behind a face which seemed to say ‘leave me alone’.

But no one did.

Word had gone round that the great saint had begun his final penance as a prelude to his samadhi.

I had gone there to photograph the seer and ask some questions but I did nothing. After seeing him through the window perching like a bird on the floor in the dim light\; his body appeared to need apparently no space. His eyes looked at nothing in particular.

I got the impression that the sage had left his physical presence behind and was away in a realm unknown to us.

The barrier of silence between me and the sage was broken by a loud conversation between an eager bunch of visiting devotees and one of swamiji’s talkative assistants.

I heard him say: “See Sir, the Periyaval does not speak. Someone ought to speak on his behalf. How else will he know about you? His life is simple. He practically eats nothing. We slip in a plate of pori (puffed rice) into his room. There are days when it is left untouched. He sweeps the room himself and refuses any help from us. We are not aware what he does inside his room. Often we find him sitting simply for hours. That does not mean he is not doing anything.”

The sun had come up right above me changing the placid blue of the morning sky into a lifeless haze. I felt I had been totally disarmed. It was time to leave.

I walked up to the window again to see what the saint was doing. He was still there on the floor in an unsleeping mass. Outside, the assistant was busy with a fresh group of visitors. The sage was silent but looked away, struggling to focus his vision beyond me and the noisy crowd.

© T.S. Nagarajan 2007

Add new comment