Latest Contributions

My grandparents, my parents, and I

Category:

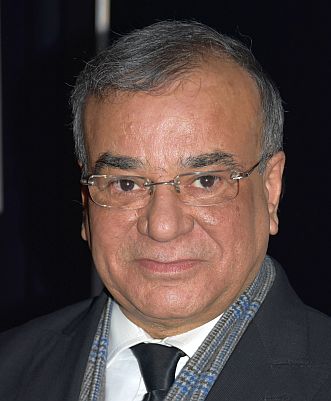

Gautam Banerji has a Master's from St Stephen's College, Delhi, an LL.B. from Delhi University, and an M.Sc.(Econ) degree from the London School of Economics. He taught at an undergraduate college in Delhi, 1973-85, and worked for UNICEF 1985-96. Then he moved to London to practice law. He served as the Judicial Advisor to the Judicial Development Institute, Baghdad, 2009-10 as a U.S. government contractor. He was a member of Commission for Sustainable London (2007-13). He continues as a Trustee and Board Member of Hindu Council, UK. Now fully retired, he lives in Dilijan, Armenia, with his wife, who teaches at United World College, Dilijan.

Mandalai, where I was born, was a quaint village fringed onto the outskirts of an equally small town in rural Bengal. Pandua, the nearby town, has a claim to connections with epic heroes of a bygone era. The Pandavas, according to legend, passed through it in their sojourns. Ruins of an old monument, rebuilt several times through its history, stand testimony to this tall claim of local residents. It’s a somewhat miniature version of the Kutub Minar and cannot be missed as the train approaches Pandua. Mandalai is only three miles away from Pandua but it’s a world apart.

A train connection linked Pandua to the twin city of Howrah-Calcutta in the late Victorian era, and still runs a busy commuter service today. At an early stage of surveying the rail route, there was talk of the train running through Mandalai, but the feudal gentry of Mandalai resisted successfully in their feudal pride. It was the lurking fear of industrialization, and Mandalai was happy to be left behind. My mother's ancestors took pride in the decision while Pandua scored over them and invited the transformation.

My Mamabari (mother's family home) in Mandalai as it stands today. Taken from its backyard orchard and pond.

Pandua today is a busy market town and a block headquarters, bustling with trade and commerce in the midst of rural Bengal. The Grand Trunk Road passes through it, linking Calcutta with Delhi. Mandalai boasts of its mango orchards besides other crops and produce that find their way to distant cities far beyond. My mother's family retains the feudal connection with all feudal pride, even though many of the present generation have moved out far and wide in search of new opportunities and ventures.

The charm of the rural countryside and my childhood association with it still beckons me to the place on every visit I make to Bengal today. It has grown into me with the passage of time and, I guess, it has shaped my identity in many strange ways.

My father, Ganendra Nath Banerji, was of humbler stock. My grandfather, Golok Nath Banerji, grew up as an orphan in Chinsurah, having lost his father at the age of three, and his mother when he was five. (I never saw my paternal grandfather. He died several years before I was born.) He was raised under the care of his maternal uncles, who were humble residents in the old part of the town, predating the Dutch settlement. By the time my grandfather was growing up as a child, there was a United Free Church Institute in the town, providing English education.

Chinsurah is a busy district township thirty miles up the river Hooghly from Calcutta, which used to be a Dutch settlement before the English arrived. It is two miles up the river from Chandernagore, the pride of French settlement in Bengal, and a mile upstream is Bandel, where the Portuguese settled for trade. The Hooghly-Chinsurah Municipality today covers Bandel and remains the seat of both the district and divisional administration. Chandernagore is governed under a City Corporation. The entire urban agglomeration along the river today, however, is a part of the Greater Kolkata (Calcutta) Metropolitan Development Authority.

My grandfather attended the English school in the town on stipend and scholarships. Then, he moved on to become one of the earliest graduates of Calcutta University in the 1880s.

He started his career as an Assistant Inspector of Schools in Hooghly district, covering as well the urban agglomeration I mentioned earlier and the rural hinterland closer to the region where I was born. There is an old High School in Ilshoba-Mandalai, which he is said to have visited for inspection in his early career. Later, he moved to Rangoon (now Yangon) with the colonial administration after his wedding, and through his wife's connections.

It is family lore that my grandfather, as a promising young man of good education, was spotted out as a suitable groom by Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Mahesh Nyayaratna, two erudite Sanskrit scholars of the time. Both rose to be Principals of the Sanskrit College in Calcutta. Mahesh Nyayaratna's older son, Manmatha Nath Bhattacharya, rose to be the first Indian Accountant General of British India. He was heading the Accountant General's Office in Rangoon when my grandfather married, and was in turn responsible for my grandfather's career move to Rangoon. My grandmother, Kumudini Devi, was Mahesh Nyayaratna's niece. She grew up under his care.

There are streets named after both Mahesh Nyayaratna and Manmatha Nath Bhattacharya in Shyambazar, Kolkata, leading to their ancestral home that still survives. Manmatha Nath Bhattacharya finds mention in the Collected Letters of Swami Vivekananda, which were published many years ago. He was corresponding with Vivekananda while the young monk continued with his mission in the US after his successful debut at the Congress of World Religions in Chicago.

Among his many other acts of benevolence and charity, Manmatha Nath Bhattacharya installed the deity for worship in the Rangoon Durga Temple, which still stands as a pride of place for the Hindu community in Burma (now Myanmar).

The major part of my grandfather's professional career was spent in Burma. Initially, in 1889, he was a clerk in the Accountant General's Office. He rose to be a Section Officer by the time he retired in 1928. The family belief is that he was confined to the grade of Section Officer for eight years on account of an adverse confidential report by his boss, which charged him with being of a "Swadeshi character". He lived for barely two years after his retirement. He passed away in 1930, when my father was twenty-three years old.

When my grandfather retired, my father had got his law degree from the Law College in Rangoon University after an Honors degree in Mathematics.

It was a freak of destiny that my parents met and got married. My mother's aunt through a common relative negotiated the marriage. My grandmother's younger brother, Rai Sahib Jogendra Nath Mukherjee, who was at a point of time the Private Secretary to the Governor of Assam in British India, was the common connection of the two families.

My father was several years older than my mother. He married late since he was busy serving in the War with a Commission in the British Army as a Reserve Officer. Many from the Bar and the Bench made it to World War II on non-combative roles, and served well with the Army in Burma Reserve Officers (ABRO). My father was no exception. He joined the War as a young Lieutenant and rose to be a Major by the time peace returned. He was able to revert to his legal practice in Rangoon soon thereafter.

Major G. N. Banerji, my father, during World War II. Burma.

During the War, my father was mentioned in dispatches at least twice for meritorious services, on one occasion having saved a district from famine through the conflict and its aftermath. This was in Mergui District of Lower Burma when he was posted there as a Major holding charge of district supplies. He was loved and admired by his peers for his hard work and integrity, and the capacity to rise up to challenges with equanimity of purpose and pride. My father was already a mature man with many accomplishments when he married my mother, Arati, in 1948, who was then only a young country girl of eighteen.

My mother's family moved to Mandalai, their country home, from Kidderpore in Calcutta where they lived, during the days of World War II because they were afraid that the Japanese would bomb Calcutta. The port in Kidderpore had already been targeted twice by the Japanese before my mother's family made the move to the safety of their feudal home.

My mother's great grandmother was the only daughter of Gangadhar Banerji, a leading stevedore at Kidderpore port during the busy days of colonial trade through it. He later went onto acquire trade and fame through his company, G.D. Banerji &\; Co., which his nephews, the Mukherjees of Bakulia acquired afterwards along with its goodwill and continued to run. Bakulia House, as their business came to be known by in later days, produced the first Indian pneumatic tyres by the brand name Inchek with Czech collaboration. Of course Dunlop sold its Indian version much earlier.

The village of Bakulia, which was the home to the Mukherjees, is only a few miles away from Mandalai on the road that links Pandua to Kalna.

Gangadhar Banerji built for himself a palatial mansion in his days in Kidderpore, from where he traded. But, he preserved an equally impressive country estate in Mandalai, where he retreated frequently with his English and other European clients to entertain and extend what was reputed to be his lavish hospitality. It is here in Mandalai that he carved out a somewhat comparatively modest estate for his daughter, Kshetramayi Devi. This came down to my mother's grandfather as a legacy.

The old house still stands in Kidderpore in a dilapidated state on Gangadhar Banerji lane.

My mother's grandmother came from a leading Zamindar family of Chandernagore known by the name of Lal Kuthi. Much of the land along the river Hooghly for the colonial jute mills was acquired from this Zamindar family of Chandernagore.

Several of my mother's aunts were wedded to equally reputed families of the days through family connections. One of them in turn married the son of Ramgati Nyayaratna, another erudite Sanskrit scholar of his times and a contemporary of Bhudev Mukherjee of Chinsurah, who led the Hindu social reforms and legislations along with Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and others through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

My mother's school education was unfortunately disrupted by the family's move to Mandalai from Kidderpore. The old Ilshoba-Mandalai High School in those days admitted only boys. It was much after my mother's wedding that they added a girls' section to it.

My mother, however, had a voracious appetite for reading from her childhood. It survived through her life. She grew up to be a widely read woman with an enviable collection of good literature in Bengali, which she brought back to India and passed on to me as my share of her legacy. I donated the books to the village library in Mandalai, when my wife and I moved to London. They still survive there today with a pride of place on the shelves.

My mother, though several years younger than my father, provided him the support and comfort he needed through life. My father survived her by ten years but missed every bit of her presence till he passed away at the ripe age of ninety-four.

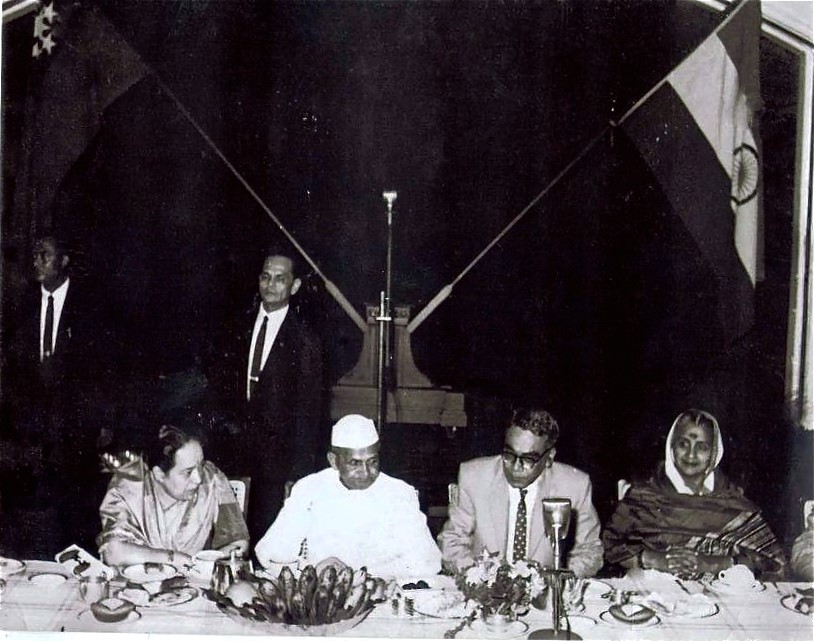

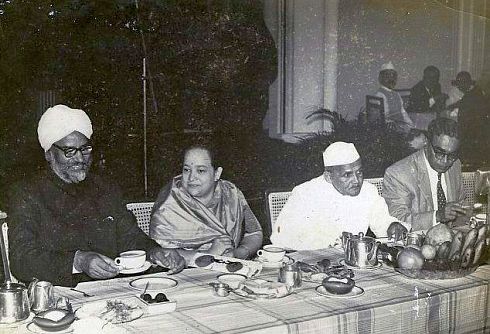

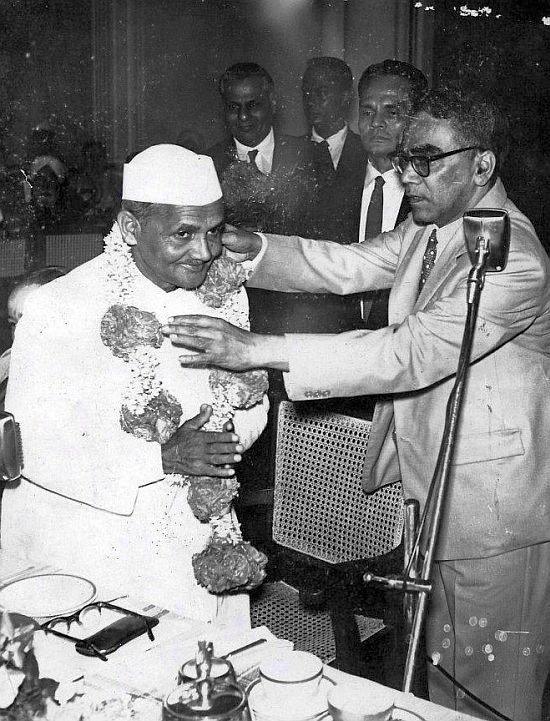

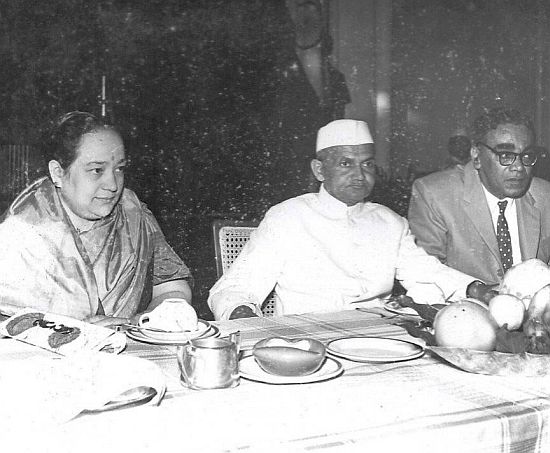

My father often recalled an incident in 1965 when Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri was on a state visit to Burma. My father was hosting the civic reception for him at the Strand Hotel in Rangoon on behalf of the Indian community, and as President of the All Burma Indian Congress. The then Indian Ambassador, Admiral R.D. Kataria, conveyed to my father that Shrimati Shastri by habit was a vegetarian like Shastriji, and did not eat food cooked outside the home. My mother took upon herself to cook for Shrimati Shastri at the local Hunuman Temple, consecrated the food as an offering to the deity, and then served it to Shrimati Shastri as prasad.

L to R: My mother, Indian Prime Minister Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri, my father and Shrimati Shastri at civic reception on Shastriji's state visit to Burma, December 1965.

L to R: Indian Foreign Minister Sardar Swaran Singh, my mother, Indian Prime Minister Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri, and my father. Shastriji's state visit to Burma, December 1965.

My father, right, welcoming Indian Prime Minister Shastri, left, on his state visit to Burma. December 1965

L to R: My mother, Indian Prime Minister Shastri, my father. Shashtriji's state visit to Burma. December 1965

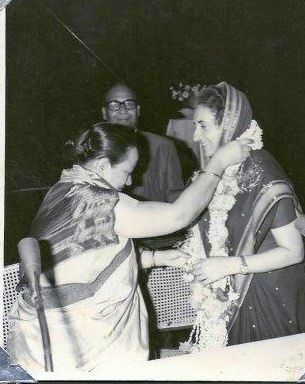

There was another incident on the occasion of Mrs. Indira Gandhi's state visit to Burma in 1967. The civic reception was similarly arranged at the Strand Hotel. My mother was tasked with the seating arrangements. There was obviously a big crowd from the community, who could not all be accommodated in the big banquet hall, where Mrs. Gandhi was to be seated. Smaller halls adjacent to it were availed to seat them.

Normally Mrs. Gandhi would have walked straight to the banquet hall upon arrival. Much to the surprise of both the Indian and Burmese security, my mother whispered to Mrs. Gandhi, when she received her along with my father, if she would make a slight detour to the other halls to greet the members of the community who may not be able to see her otherwise. Mrs. Gandhi agreed.

My mother, left, welcoming Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. State visit, Rangoon. 1967

I have a wonderful press photograph of Mum leading the way through the crowd with Mrs. Gandhi close behind her heels and the Indian security along with my father trailing further behind. My father was equally taken by surprise.

My mother in the foreground, right, with Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi close behind on arrival at the civic reception: Strand Hotel, Rangoon, 1967. My father is close behind Mrs. Gandhi, and the Indian Ambassador, Admiral Kataria, is behind him next to the Burmese security officer.

My mother, left, with Indian Prime Minister Gandhi, in a pensive mood, at the civic reception on her state visit. Strand Hotel, Rangoon, 1967.

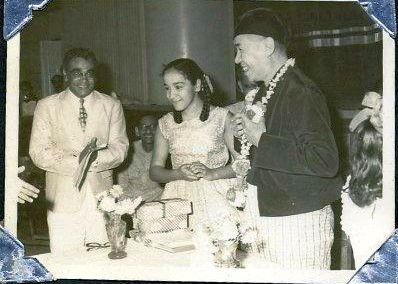

L to R: Indian Ambassador to Burma Admiral R.D. Kataria, my mother, Indian Foreign Minister M.C. Chagla, and my father, standing. Father, in his capacity as President of the All Burma Indian Congress, welcomed the Foreign Minister, Rangoon, Burma. 1967

L to R: My mother, my father and Indian Foreign Minister Shri M.C. Chagla. Rangoon. 1967

After my parents got married, my sister and I were born in quick succession, barely a year apart. We all moved in together as a family from Mandalai, where I was born, to join my father in Rangoon. I was six months old when we made the journey in late 1950, around Christmas time. I preserve some wonderful memories of my childhood in Burma with my family and friends.

My earliest memory of a place of worship is of climbing the stairways to the shrine at the Shwe Dagon Pagoda in Rangoon, probably in 1953 or thereabout. I still vaguely recall toddling up the steps that looked so formidable if not insurmountable in my childhood. There was a pride of accomplishment as I finally made it to the top. I grew up in this Buddhist country, born into what I would call today a reformed Hindu family. We lived in a busy downtown neighborhood of Rangoon, which in those days preserved its cosmopolitan character and identity.

There were two mosques close to our home. We woke up each morning with the call to prayer by the muezzin. The diversity all around seemed all so natural and I experienced no difficulty as a child to communicate in at least four languages: English, Burmese, Hindi and Bengali. To me that seemed to be the norm, and it has helped me ever since through my life as I look back in time. There was never the lurking fear of the ‘other' to push me into parochial solitude.

My pre-primary and kindergarten schooling was at a Roman Catholic institution. Then, I moved to the Methodist English High School (MEHS) in Rangoon at Year 1 to complete my primary schooling. MEHS was then a premier institution for English education in Burma, run by many dedicated expat teachers from the UK and the US.

Mrs. Logie headed the school. Mr. Fuller, Mrs. Brindley, Mrs. Braidey, Ms. Sen were some of the teachers. Mr. Henderson, who later migrated to Australia with his family, had a charming daughter, whom I admired and who joined us for the Youth Fellowship in the school chapel every Sunday morning.

Luckily, the school offered Hindi as a second language, having French and Burmese as other options. Upon my father's insistence, I was offered Hindi as my second language. Mr. Dixit was our teacher. The medium of instruction of course remained in English. I have a claim to a better knowledge of Hindi than Bengali as a consequence, although the latter was my mother tongue.

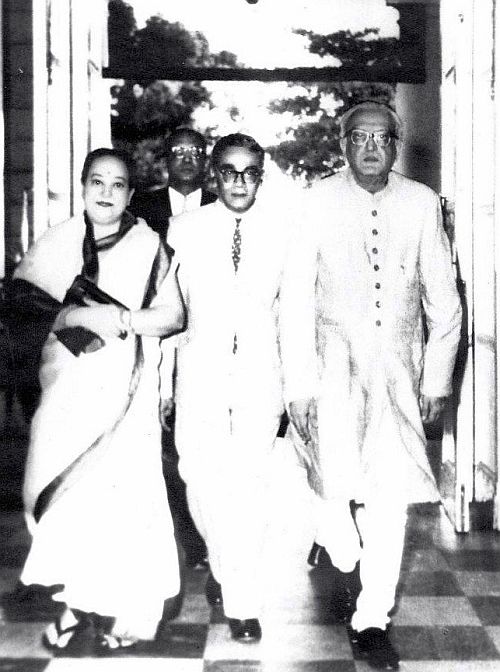

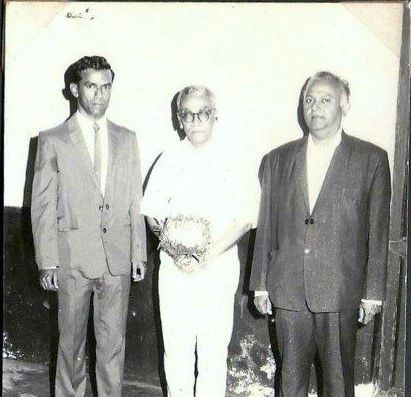

My father, right, being garlanded at a civic reception. Rangoon. Circa 1960s.

Left to right: My father, my sister Sapna and Dr. Ba Maw, mid-1960s, Rangoon, Burma. Dr. Ba Maw was the President of Burma during the Japanese occupation of Burma in the 1940s.

My mother, centre back row, with her cultural troupe, flanked by Indian Ambassador R. D. Kataria (in dark suit) and Mrs. Kataria. Lawns of India House. Rangoon. Indian Republic Day celebrations.

Subsequently, I continued with Hindi through my High School at St. Paul's in Darjeeling, where I moved in 1962 at the age of eleven and continued to complete my schooling in 1966. I joined St. Stephen's College in Delhi in 1967.

My Bengali today remains somewhat refined through self-study. However, it tends to be somewhat ‘bookish' in my wife's opinion with her deep roots in the urban refinements of Calcutta. My knowledge of Hindi stood me well in Delhi through my college education, and in my early working years.

We in our generation were raised to be more English than an Englishman. That was a middle-class aspiration of the Indian underdog, and I was made to live through my father's dream. He was no less English and a ‘conservative' to the core. He admired Maggie Thatcher. He thought Yasser Arafat was an ‘outlaw'. He admired the strides South Africa was making in development and progress under the apartheid regime. That's when I parted company with him. In the 1970s, I started writing for Mainstream, a left-wing political magazine published from Delhi.

I was a disappointment to him - no doubt about that.

To add salt to his wounded pride, I flunked the Indian civil services exams twice. I scored well in English Literature (86%) but failed in European History (34%), a subject I thought I understood well. My Marxist-Leninist perspective was obviously unpalatable to the examiners raised in the best of English colonial tradition.

I had no regrets as I continued with my teaching at College of Vocational Studies, an undergraduate college of Delhi University, after completing my Master's degree from St. Stephen's College in 1973, having spent a year (1970-71) on an exchange program at Keio University, Tokyo, from St. Stephen's College. It left me loads of time for amateur histrionics with a theatre group of left-wing intellectuals and for subscribing to the left-wing political magazine. This continued for twelve years.

I had always remained somewhat unconventional in my views. This irked my father no less. He had a doggedness of purpose, which I lacked. He rarely gave up. Perhaps, this explains his success as an advocate in the courts.

He reached the peak in his legal practice with a commanding reputation by the time I was growing up. He hoped against hope that I would join him someday. Moreover, he commanded respect in his community, and led the All Burma Indian Congress as its President from 1964 to 1975, when he finally returned to India. At that time, the All Burma Indian Congress was the central organization representing the Indian community in Burma.

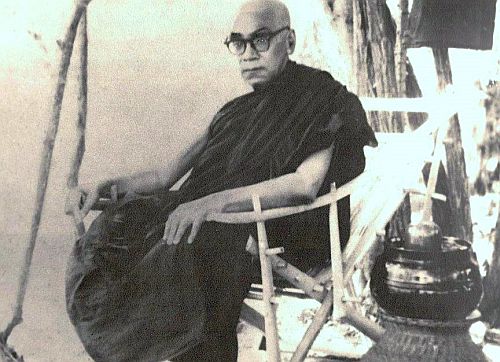

My father in his ochre robes as a Buddhist monk in Burma. About 1967.

The old leather-bound editions of the All India Reporter (AIR) of reported cases from the High Court in Rangoon dating back to the 1930s (when the AIR still did a combined reporting for both Burma and India under British India) still figure a number of landmark cases in which my father appeared successfully, and which set precedents through the legal judgments made. This was no doubt at a very early stage in his legal career. He returned to his legal practice in Rangoon after the War, where he continued till 1975.

He was the Honorary Legal Adviser to the Indian Embassy in Rangoon through the turbulent days of 1960s. At that time, there were rapid constitutional changes in Burma, which in turn impacted upon the Indian community. Several letters of appreciation from the Indian Ambassadors, who worked closely with my father on repatriation of Indian nationals, bear testimony to the yeoman service he provided to his community for a smooth transition to a new life in India. I still have the letters preserved.

My father, center, on the eve of his departure from Burma at a farewell at the Kali Temple, Rangoon with fellow trustees. He was a trustee of the Kali Temple Trust. 1975.

In a sense, my father died a disappointed man. Still, he was almost prophetic in stating that my younger daughter, Manda, would make it with flying colors in the legal profession. I guess she is moving that way already as a young Solicitor with an East Midlands heavyweight law firm in Nottingham. She has already made a reputation in her profession for her advocacy skills and has the honor of being the regional representative of young lawyers at The Law Society in London. My father believed that she was a Margaret Thatcher in the making. I am not so certain, though, if she holds Mrs. Thatcher's views.

I did get a law degree - it was a choice I made much later in life to join the profession when my father had already retreated into retirement. By then I had also done a Master's program at the London School of Economics (LSE) in Social Policy and Planning, besides a few other short courses in international studies at the LSE and St Petersburg, Russia. My father lived barely two years through my legal career spanning from 1996 to 2014 initially in Calcutta, and then in London, after I took early retirement from UNICEF. I recall, his father had also passed away soon after he joined the profession. What a coincidence!

______________________________________

© Gautam Banerji 2017

Comments

Add new comment