Amrita Patti (1923-1997) by Sujata Srinivasan

Category:

Sujata Srinivasan is a Connecticut, U.S.-based journalist specialising in business and economic development, as well as community and general interest features. She and her husband Arun enjoy the theatre, travelling, and classical music, among many other things.

I loved to nestle against my Patti, which means grandmother in Tamil. She smelled of all my favourite smells – Mysore Sandal soap, shikakai, and soft, sun-dried Pochampalli saris. And when she smiled, which was often, I felt as though all was indeed well with the world. My world, at least.

The world Patti created for me consisted of Shakespeare and Jane Austen, whose works she enjoyed and recited from her memory – especially Othello’s soliloquy after he murders Desdemona, and Mark Anthony’s eulogy of Caesar, which she narrated to me when I was just seven or eight years old\; the fragrant smoke of sambrani (incense) on a charcoal fire, which wafted from an inverted, woven cane basket on which Patti, my amma (mother) and I spread our hair after an oil bath\; Sanskrit, at which she excelled and taught me\; and soft-as-jasmine idlis, Mysore Pak that melted in your mouth, and fiery red Puliyodharai that brought on the tears and yet one wanted to keep on eating, for none could make it the way she did. Alas! Though she passed on to me her love for cooking and feeding family and friends, the spices in my kitchen don’t smell half as enticing as they did in hers.

From Patti’s Kitchen to Yours

Here are Patti’s Puliyodharai and Mysore Pak recipes, as remembered by my mother, who was unable to provide Western-style measures and cooking times, since, like her mother, she cooks by intuition. Amma learnt these recipes when she was a young girl by helping Patti in the kitchen, the same way I learned to cook – by helping my amma and Patti.

Puliyodharai

This recipe has a Mysore influence since my grandfather was from that region.

Ingredients

- Tamarind (the size of two big lemons)

- Grated jaggery (3/4 the quantity of tamarind)

- Turmeric powder (3/4 teaspoon)

- Rasam powder (2 tablespoons, homemade)

- Curry leaves (1 sprig)

- Groundnuts (3/4 cup)

- Cashews (2 tablespoons)

- Mustard oil (as required)

- White rice (2 cups)

- Salt (as required)

For seasoning

Mustard seeds, Bengal gram dal, red chillies (Bedigai variety), urud dal, asafoetida, Cobri (1 cup of grated dried coconut – do not use fresh coconut)

Procedure

Soak the tamarind in hot water. After an hour, extract the thick liquid, filter it, and boil it. This is called gojju. While the gojju is boiling, add half of the quantity of jaggery, salt, turmeric powder and rasam powder and allow it to boil into a semi-solid paste. Add 3 tablespoons of mustard oil to the gojju.

Take a pan, add mustard oil for seasoning. When the oil is hot, add the mustard, urud dal, Bengal gram, red chillies, curry leaves, groundnuts, cashews and asafoetida. Fry until golden brown and keep aside.

Soak the rice in water for 10-15 minutes. Cook rice udhirudhir (dry, non-sticky) by adding just 1 3/4 cup of water. Spread the cooked rice to cool on a tambalam (wide plate). When the rice cools, add the gojju. Then add the seasonings and salt, mix well. Finally, add the raw cobri. While mixing the gojju and the rice, be careful to not turn the rice into a mushy mix.

Serve with fried appalam (South Indian papad) and/or vetthal (rice crisps). Spicy potato curry and thair vadai (lentil dumplings in curd) are perfect combinations.

Mysore Pak

Ingredients

- 1 cup Bengal gram flour

- 1 ¾ cup sugar

- 2 cups ghee (clarified butter)

Procedure

Dissolve the sugar in a pan with the required amount of water and boil it. Let it reach kambi pagu consistency, that is, when a spoon is removed from the syrup, there should be a continuous string. When this happens, add the Bengal gram flour and keep stirring constantly to avoid the formation of lumps. Slowly, start adding the ghee to this mixture. When the mixture does not stick to the pan, pour it onto a greased (with ghee) wide plate. Allow it to cool and cut it into diamond or square-shaped pieces. Well-made Mysore Pak must melt the moment it touches one’s tongue!

Early years

Patti said that when she was a young girl – oh how I loved to hear stories of her childhood – her mother Pankaja, my great-grandmother, despaired that her daughter was a tomboy. Indeed, when Patti saw the music teacher coming to teach her at home, she would promptly climb a tree and refuse to come down. Patti and her siblings grew up in a huge house with vast grounds in Villivakkam. It was customary for girls to learn Carnatic music, and often, musicians came home to teach lessons. Her sisters, on the other hand, were diligent students and one of them, Seetha patti, became a proficient singer.

“Now I wish I had learned music when I was young,” Patti regretted later in life, although she could easily identify ragas and hold a note impressively well. “Of what use is tree-climbing?” she asked. She made sure that my mother learnt Carnatic music the traditional way, and in turn, my mother made me take music lessons when I was growing up.

Patti was the ringleader among her playmates and her wicked sense of humour was evident from early on. There was a young girl named Satyavati in the neighbourhood who put on all sorts of airs and pretended that she was a princess. My Patti and her friends would bow down to Satyavati and offer to be her subjects and palanquin-bearers. They carried the proud and excited girl on their shoulders, yelling “Satyavati ki jai!” – Victory to Satyavati! Then, suddenly, they would drop her into an open storm drain. This happened time after time and poor Satyavati never caught on. “She would be covered in mud and rotten leaves and start to cry!” Patti would giggle, recalling the incident.

Patti enjoyed making fun of others. When one of her nieces by marriage wanted to know how she too could have long and thick hair like Patti, my Patti told her to rub stinky castor oil in her scalp and sit facing the rising sun for half an hour each day! The poor girl actually followed this instruction dutifully!

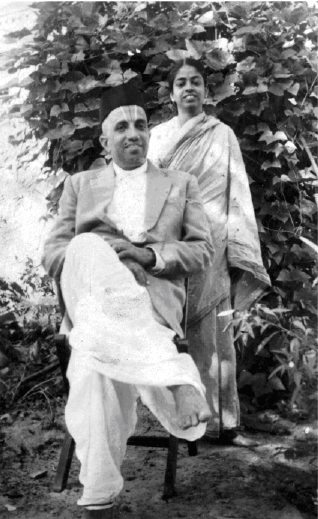

Patti and thatha in the early years of their marriage in the 1940s.

After completing high school in Villivakkam near Chennai (formerly Madras), Patti had an arranged marriage at the age of 19 in 1942. My mother told me that it was a simple wedding ceremony, as the British discouraged public celebrations – including long-drawn weddings – because of blackouts and other restrictions during World War II.

In the early years of her marriage, Patti had lived in a joint family in Coimbatore where perianna (elder brother), my grandfather’s oldest brother, was the head of the household. The norm was that perianna would personally purchase everything that was required for the household. Yet, once Patti and thatha’s youngest sister Kamala, who was not yet married, felt a bit adventurous and decided to go to the market all by themselves.

As the two young women set off, skipping and giggling over their rendezvous, they noticed perianna’s car drive by. The window rolled down and perianna himself – oh no! – looked at them for a second before driving on.

Kamala patti became a bundle of nerves. “We’re in big trouble, Amrita akka (older sister). This is it,” she kept repeating to my grandmother.

When he reached home, perianna went straight to his mother and asked her, “Are you aware of the kind of unacceptable things that are happening in this home? Please make sure they don’t happen again.” My great-grandmother, Doraiamma patti, was alarmed. “What things? What are you talking about?” Perianna refused to elaborate, and Doraiamma patti had to unravel the mystery on her own. Of course, that was the last time Patti and Kamala patti went to the market on their own.

My years with her

Patti and thatha lived about 25 minutes from my parents’ home. My father, a stockbroker, was on the board of several companies and non-profit organizations. My mother, a homemaker, kept up with his myriad social activities. During my younger years, until about the age of 12, I was often dropped off on evenings and weekends at Patti’s home so my parents could meet their social obligations – the two of them have done an extraordinary amount of social work for various causes in Chennai. Besides, many of my after-school activities such as dance and music classes, and Hindi tuition, were located near Patti’s home. Patti brought freshly-squeezed mosambi (sweet lime) juice to my dance sessions and shed copious tears as I depicted the stories of Hindu gods and goddesses through dance. Besides, amma packed me off to Patti’s place if she felt I needed to be disciplined. “There’s too much chellam (petting) from appa (Dad) and his side of the family! You’re getting spoiled!” she’d grumble good-naturedly.

In the early 1980s, the milkman and his cow Lakshmi came to Patti's house in the morning to provide milk. ©T.C. Nagarajan 2008

At Patti’s home in the 1980s, each morning, the milkman would come with his cow, Lakshmi. He milked Lakshmi into one of his tall cans, and then transferred the milk to the vessel that Patti used for milk.

But first, he had to show Patti his can so that she could make sure it was empty.

“See ma, it’s empty. Will I ever cheat you by diluting the milk with water?”

On mornings when Patti was busy with other things, she would entrust me with the important task of inspecting the milkman’s can. I took this very seriously, for she had placed her trust in me. This task was taken over by Anupama maami (maternal uncle’s wife) when my mama got married. A few years after that, the milk began to arrive in Aavin Dairy packets.

“Show me the can,” I would demand of the poor man. “The little one is as strict as you are, ma,” he would complain good-naturedly!

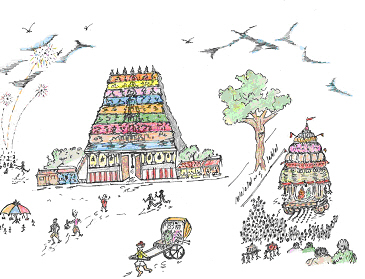

Often in the evenings, Patti and I went by rickshaw to the historic Kapali temple in Mylapore, Chennai. We would clap our hands and sing together a verse she had composed in Tamil:

Kapali kovilukku pogalama?

Andha Karpagathai kan kulira parkalama?

Shall we go to the Kapali temple and gaze at goddess Karpagam (Shakti) until our eyes cool with satiation?

Sujata and her Patti often visited the Kapali kovil (temple) in Mylapore in Madras (now Chennai). ©T.C. Nagarajan 2008

After the darshan, we would always visit the roadside shops where she would buy me choppu – miniature kitchen items made of wood, plastic or steel. To a little girl, this was the kind of stuff that heaven was made of!

Speaking of heaven, Patti, a devout Hindu, believed in karma. “What goes around comes around,” she would say, and make up fascinatingly macabre stories of how Yama treated sinners in hell!

“First, he’ll give the sinner back his human form. Next, he’ll toss him into a giant cauldron full of boiling hot oil. Of course, the sinner will be fried and eventually die in agony. Then, Yama will bring him back to life and toss him back into the cauldron. This he will do for all eternity,” she said.

“Eternity?” I would gasp, each time she narrated this.

“Eternity,” she would confirm, with a twinkle in her eye. I was not sure if she was serious. Patti could pull a fast one with a straight face.

Patti valued education immensely …

Patti, the daughter of a school principal, knew the value of education. As a teenager at a time when children did not question their parents, she mustered the courage to ask her strict father whether she could become a lawyer. My great-grandfather, Sundaravaradachari, had looked at her sadly and said, “I have two more daughters to marry off after you. How can I afford to educate you as well? Sorry.”

Patti empathised with him. “He did what he could. He had ten children, six girls and four boys. He worked hard, saved his money, got a pair of diamond earrings for each of us girls, and when the time came, he made sure that all of his daughters had a good wedding ceremony,” she said.

“But he educated your brothers!” I would protest. This did not change her views.

“My muthanna (oldest brother) was very smart from a young age, and deserved to get a good education,” she told me. She narrated an incident to drive home how clever he was. When Patti was in the first grade, she had learned an English rhyme that she and her friends sang when they got together at home. It went thus:

Iyer thunder, Iyer thunder

Aandondoo Aandondoo

Pittapatta danda, pittapatta danda

Ambattur, Ambattur

(Ambattur is a suburb of Chennai)

Muthanna happened to be passing by and was baffled by the song. He sat down and asked the girls to sing the rhyme repeatedly, one word at a time. Finally, this is what he deciphered:

I hear thunder, I hear thunder

Hark, don’t you? Hark, don’t you?

Pitter-patter raindrops, pitter-patter raindrops,

I’m wet through! I’m wet through!

Muthanna went on to become a Supreme Court lawyer, and another brother, Raman, also became a lawyer. Durai, the youngest, became a scientist who earned two PhDs.

“That’s how it was in those days. Parents would educate their boys,” Patti said, shrugging her shoulders. “But I am praying to God that in my next janma (birth) I will become a lawyer. In my next janma, I want to learn Carnatic music and Bharatanatyam, play tennis and drive a car.” In a way, Patti fulfilled her wish during her lifetime through her youngest son Sridharan, who became a lawyer.

… And caught up in her old age …

With marriage, Patti’s formal education came to an end. Or, so it seemed at that time.

Years later, at around the age of 65, she began to study Sanskrit and went to college to obtain her bachelor’s and master’s degrees. The contact classes were held at Navasuja in R.A. Puram, Chennai, which now houses a wing of the state-of-the-art eye hospital, Sankara Nethralaya.

“I’m 65. Yet see how good my memory is!” she would boast, after narrating passages of Sanskrit poetry by the legendary Kalidasa, one of her favourite poets. “Kalidasa is known for the beauty of his upama (similes),” she would explain, and in a sweet, singsong tone, chant the opening verse of Raghuvamsa, one of Kalidasa’s epics.

Vaagarthaaviva sampraktau, vaagarta pratipattaye

Jagata pitarau vandae, parvati parameshvarau

“Vaagartha – words and their meaning. Just as words and their meaning are inseparable, so also are the parents of this world, Parvati and Shiva,” she elaborated.

There were three things that drove Patti to excel in Sanskrit – her love for learning in general, her love for Sanskrit in particular, and her competitive streak. Oh yes, she was competitive!

Patti often studied together with her classmates, all of whom were about 20 years younger than her. Many were married and had kids who also studied Sanskrit with them. Patti’s prized goal, which she achieved, was to speak fluently in Sanskrit with the Kanchi Sankaracharya, a Hindu pontiff. The students took turns hosting the group each week at their homes, and offered tiffin (snacks) at the end of the session. When it was Patti’s turn, her entire house would be filled with the aroma of pumpkin halwa, potato bonda or some other mouth-watering delicacy that she had prepared.

“Aruna (mother of the well-known Carnatic musician Sanjay Subramaniam) is simply brilliant. Plus she’s much younger, so it’s easier for her to absorb the lessons. Naturally, she is going to top the class,” Patti conceded. “But I am going to come second!”

Patti (centre) at her daughter's wedding in August, 1974. At Patti's left is a friend.

She would wake up at 4:00 in the morning and go over her class notes, softly reciting the verses. “This is the best time to study,” she said. I believed her, since she scored top marks in all her exams. When I had to study for my own exam at school, she would wake me up at around the same time, no matter how much I resisted! We sat next to each other, Patti and I, studying until the noises of the day began.

… Even though thatha was not interested

My grandmother was determined that unlike her, my mother should get a college degree before she got married. This was not easy since Rajagopal thatha (1912-1995), my grandfather, did not think it was necessary for a woman to study beyond high school. “My mother fought for me and so I went to college,” my mother told me.

Patti continued to educate herself informally even after marriage. “I read books and newspapers,” she said. “Your thatha is a good man, but books don’t interest him,” she told me. Theatre wasn’t his cup of tea, either. “Once, in the middle of a play when Othello was about to deliver his monologue, thatha committed the unforgivable blunder of asking me if the play was over, and could we please go home?”

Thatha was one of the kindest and most short-tempered men I’ve met! He was quick to boil over and quick to cool down – impulsive, emotional and deeply affectionate. For years, he was a senior executive at a well-known company in Chennai until, one day, he abruptly resigned on what he later explained was “a matter of principle.” He then ventured into entrepreneurial waters with disastrous results. The family had to move from their beautiful, three-storied bungalow (which had hosted several family weddings) on Edward Elliots Road, give up their servants, their Austin A40, chauffeur, the whole works.

Patti and thatha in their golden years in the 1980s.

Soon after, thatha turned to religion to anchor him and became increasingly ritualistic. He spent nearly an hour each morning painting the naamam (religious markings) on his forehead. The white U-shaped lines drawn with calcium represented the god Vishnu’s feet, while the thinner red line in vermilion symbolized Vishnu’s consort goddess Lakshmi. “They are my divine parents,” he would say.

Thatha also kept madi, a ritual observed during certain times of the day preceding worship. He grew his own flowers – gorgeous hibiscus and parijatham (jasmine family) – to offer to the various deities. I spent many a happy hour with thatha, joyfully making pathis or deep mud grooves around the plants so they could hold water.

Straight from his bath, a wet towel still around him, thatha began his preparations for the morning prayer. Madi rules dictated that a person observing madi should not have any physical contact with other people. As a child, I thought it was very amusing to give him a hug or poke him gently with my finger when he was in madi! Poor thatha never complained. He would quietly go and take a bath and start the process all over again. This delayed lunch and Patti became annoyed with both thatha and me.

Modern ideas and traditional beliefs

All her life, Patti wanted her independence, above all else. But that was not to be. Owing to their weak financial position, and in keeping with the social norm, she and thatha lived with their son, my mama Ravi, who was very loving to them and took care of all their needs. Yet, Patti often wished that she were financially independent. She taught Sanskrit at the D.A.V. Senior Secondary School in Anna Nagar for some time, but after retirement, was entirely dependent on her grown children.

“A woman should never be dependent on anybody, except her husband,” she would say to me.

For all her modern views about women’s independence, surprisingly, Patti also had some very conventional ideas. For instance, she held on to the notion of traditional gender roles. “However educated a woman might be, it is her duty to take care of the home and children. On the other hand, udhyoham purusha lakshanam (a man’s adornment is the job he holds). It is his duty to provide,” she’d say. Whenever she visited our home, she would be most displeased if I asked my younger brother to help with the chores. “See, she’s making the boy do the housework!” she’d complain to my mother, much to my anger and annoyance!

“Patti, when I get married, will you and thatha come and live with me?” I asked her.

“We will visit you, but we cannot live with you. Your husband will not want us all the time!” she said.

“Yes he will! If I ask him!” I said, and Patti would laugh and pinch my cheek.

“I will visit you often if his ways are compatible with mine,” she said. “Imagine if there’s mutton curry in your fridge. Narayana! Narayana!”

Sadly, Patti passed away in 1997, four years before my marriage to Arun. Each would have enjoyed the other’s company and Patti would have loved Arun -- and not just because he is a vegetarian! He became one after our marriage, and I had absolutely nothing to do with his decision – maybe she did, somehow! Incidentally, I have fallen in love with Arun’s adorable grandmother, Nappinnai – another remarkable woman. The wife of a former high court judge, she engages in organic farming in Tamil Nadu, helps the farm workers and villagers with their troubles, reads voraciously the works of Aurobindo and the like, and leads a Gandhian lifestyle.

As was the norm (and still is in some Brahmin homes), Patti did not allow her non-Brahmin maid to enter the kitchen or storeroom. “For cleanliness reasons,” Patti explained lamely. Yet, she funded the maid’s medical expenses, her child’s education, marriage, etc.

To this day, I cannot understand or get over the fact that Patti wanted to die a sumangali (married woman), and not as a widow. So when thatha died before her, she lost not only him, but also lost her ideal of dying a sumangali. “I thought I had enough punyam (good karma) and would go before him,” she told my mother and me.

The final triumph

None of us dreamed that Patti would die the way she did, of uterine and lung cancer. She was, as we expected of her, a fighter until the very end.

“When this woman, who showed such strength and endured so much in her life, did not have the lung power to blow out even a tiny candle, it broke my heart,” my mother said to me in tears.

“It’s this horrible cough, Kausalya. Otherwise I can blow out this little candle,” Patti had told her.

Although the cancer had spread extensively in her lungs, Patti was determined enough to take her M.A. Sanskrit exam. But she did not live to see the results, which came in the mail a few weeks after her demise. She had passed with flying colours.

I have a feeling that Patti’s dreams have come true. That she’s out there somewhere, learning Carnatic music and Bharatanatyam, and playing tennis. Something tells me that she’s on her way to becoming one of the smartest prosecutors in the world. I can see her striding confidently into the courtroom, briefcase in hand. Watch out defence. Here she comes!

© Sujata Srinivasan 2008

Comments

Add new comment