My Early Years - 2

Category:

Tags:

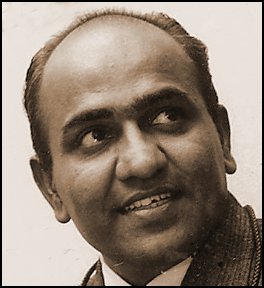

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

Editor's note: This story is reproduced, with permission, from Mr. Nagarajan's second not-for-sale book of his memories, Self-Portrait: The Story of My life, 2012. This website has several excerpts from his first not-for-sale book A Pearl of Water on a Lotus Leaf &\; Other Memories, 2010.This is the second of three sequential stories about his early years. The first story is available here.

My father had to move again from Mysore to Doddaballapur, near Bangalore. He decided to leave the family behind in Mysore so that the children's education was not disturbed and preferred to take me with him. I was waiting to join the high school. In Doddaballapur, my father arranged with a local ‘mess' run by a Palaghat Iyer for our meals. He was an old man with a flowing beard.

He looked like the Rishi in a Ravi Verma painting reproduced in a calendar we had at home. Every day, a young man from the ‘mess' brought us our food, hot and delicious, in a shining brass carrier. My best friend was a boy of my own age who worked as a servant in the jeweller's home. We went to the same school, the Government High School. His name was Rudramuni. In addition to his studies, Rudra had to help the jeweller's wife in the household chores. Since he was not very good at his studies, I helped him finish his school homework.

Freedom Day

Even after 60 and odd years, I am able to recall in detail those early years of my life. But, I remember very little of what happened in our town on the day India became independent. One possible reason is that the significance of this historical event was felt less in the small towns of south India. Another reason is that perhaps not much happened, at least where I lived. We had no radio at home. Only a Kannada newspaper arrived every morning, which, after my father finished reading it, was collected by Rudra for the jeweller to read. It was rarely returned.

Independence Day 1947 was a holiday. We went to the school without our books in the morning to take part in the flag-hoisting ceremony. More than the significance of the day, the holiday from school meant much more to Rudra and me. At school, we were given little paper flags, which we pinned proudly on our shirts. In addition, volunteers gave us each a white ‘Gandhi cap' to wear. My father went to work and came back as usual, and did not talk about the big day. But, the extra sweet dish in the brass carrier that arrived from the Iyer mess made all the difference to me. Gandhi, Nehru and Patel were names with which I was familiar. They were the names I heard whenever the Congress party organised street processions. I made it a point to join such processions, and walk with the slogan-shouting men and women. This gave me a special thrill, although I knew very little about what the slogans meant except that they were either against the British or in praise of our leaders.

In contrast, the day Gandhiji was assassinated in 1948 remains etched in my mind. I was taking part in an RSS (Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh) drill in the maidan (open field) when the news came that Gandhiji was dead, shot by an assassin. The local RSS leader, a young man in his twenties, who was conducting the evening programme announced the sad news and urged us to go home. My father had returned from his evening walk. I saw him engaged in a serious talk with the jeweller. The jeweller's son, who used take part in all the Congress programmes in the town, was crying. I did not cry but I think I experienced a strange loss. After all, Gandhiji was dear to all of us. I heard groups of people running on the street urging shopkeepers to close. Strangely, the meal carrier from the ‘mess' did not arrive. My father too did not utter a word.

Malavalli

We stayed in Doddaballapur just for a year and again my father was asked to move to a place called Malavalli in Mysore district to take charge of the hospital there. I had to move with him though I had just completed only the first year of my three-year high school studies. There was no choice. I made up my mind to accept the change.

Malavalli, a bigger town than Bannur, was totally a different experience. I had to go to a new school, make new friends and even learn cooking. We moved into a tiny little cottage meant for the doctor in the hospital compound. It was nothing but a dilapidated building which did not appear lived-in. In fact, before we moved into it, the hospital staff advised my father not to live there because the house was ‘haunted' by the ghost of a lady who visited the house at nights. My father's predecessor too did not live there. Safely he had taken a house on rent in the town. Ignoring all advice, my father got the house cleaned up\; white washed and made it liveable.

There was no arrangement to get ‘Carrier Meals' from anywhere. The Bus Stand Hotel across the road did provide ‘Plate Meals', the quality of which was so bad that it was unsafe to depend on it. So I had to take over the cooking in addition to going to school. My mother came from Mysore briefly to give me basic lessons in cooking. She taught me how to cook for just two of us. There was a Kerosene stove. I got up early, had my bath and cooked the day's meals and went to school. It was my father's job to provide hot water for baths, which he did by heating a huge copper vessel fixed in a corner in the bathroom using firewood. He would do this before he retired at night so that hot water was ready by the time he got up in the morning. There was no Puja room\; but he didn't miss it. I had never seen my father do any kind of worship. I had never seen him prostrate before any idol. He never talked about God. Till his end, I had no clue to his beliefs or disbeliefs.

Visiting Apparition

The thought that we were sharing the house with a visiting apparition kept coming back to me. I had no fear but I was only curious. I broached the matter with Shamanna, whom father had fixed to bring drinking water from a lake on which the entire town depended. He worked for a number of households. He spent the entire day in making several trips to the lake and brought water in a large brass vessel carrying it on his shoulder. This was his only source of income.

Shamanna was an amazing person. He kept a smile on his face despite many odds. His wife was mad. All day she roamed about the town talking to herself. Children ridiculed her, even threw stones at her. The poor Brahmin had to search for her every evening and take her home. He wore just a white dhoti which he folded and tucked the end at the waist. Only the sacred thread adorned his torso. He was short, stocky and clean shaven with just a thin pigtail which was tied at the end into a tiny knot. Part of his protruding paunch hung from his waist. His ebony skin shone in the sun and the large eyeballs made him look frightening. When he moved about the house in the dull light of the dusk, he looked like a friendly apparition himself!

I did not notice any supernatural activity in the home. The house stood alone within the large hospital premises with not many houses around. At nights, I could hear the sound of buses and lorries plying and, occasionally, a dog barking in the distance. Shamanna, who believed in the ghost story, had warned me to be very careful in moving about the house at night. He had told me that if I heard eerie voices or smelt strange perfumes not to get up and check. If any door closed or moved without reason, I should straight away conclude that the lady was coming in. If I felt that something unnatural was happening, and got up from sleep, he had advised me to just close my eyes and utter repeatedly "Rama, Rama" till I went to sleep. "If you don't meddle with her, she wouldn't hurt you." he told me confidently.

I refused to believe Shamanna because he had never spent a night in the house. His entire story was based on hearsay and imagination. I was unable to keep awake at night to keep a watch on the visiting lady. My father and I slept in the same room. He slept on the bed and I on a mattress on the floor. I had not seen my father smoke in the house. He would wait for me to fall asleep and light a cigarette while lying on the bed. On some nights,

I would pretend as though I was sleeping and wait for the father to light his cigarette. I derived some thrill in seeing the red glow at the tip of the cigarette as he smoked. I never talked about the ghost with father. Perhaps he was under the impression that I was unaware of the story. Months passed. Nothing unusual happened. Life went on peacefully.

One night I was woken up by father. The main door was open. I found a bullock cart with one or two people waiting in front. All the lights had been switched on. Father was getting dressed. He came to me and said that he had to go urgently to attend to a critical case in a village. He told me to bolt the main door and advised me not to open it for anyone. "Keep the lights on and go to sleep. I shall be back in the morning." he said and left. I was thrilled on being left alone at night. Here was an opportunity for me to investigate the ghost story. I thought if I kept the lights burning the apparition may not come. I switched off the lights, kept the main door opened and sat in total darkness in the living room, waiting for the spiritual entry. Hours passed. Nothing happened. Not a sound. Not a door moved. Sitting in the chair, I must have gone back to sleep. I woke up alarmingly when I was gently shaken by a soft hand. It was father who had returned at daybreak.

City Life

Our stay at Malavalli was very short, just a year. My father was transferred back to Mysore, the last posting before he retired from service. I was thrilled to go back to Mysore and join the family. It was my third and last year in the high school. I got admission into the Maharaja's High School, which was within walking distance from our home in Chamaraja Mohalla, across the famous "100-ft road" in the city. The rented house was too small for the large family. Apart from my eldest brother Satyan, who had found a job in Bangalore, the rest of the family was in Mysore. With father and I coming in, the house was crowded. My grandmother (mother's mother), after she became a widow, also lived with us. My mother's younger brother, Ponnu Swamy, whom we called Ponnu Mama, a bachelor, who had no home of his own, also joined the family\; and there was my father's bicycle to boot. (Editor's note: A detailed story about Ponnu Swamy is presented in Uncle Ponnu.)

After having lived with father in comparatively spacious official residences, I found the house small and uncomfortable. There was only a single bathroom and a tiny lavatory. Every morning, we vied with one another to use the limited facility. There was a room upstairs and a small open area to dry clothes. The women slept in the hall\; my father in one end and the grandmother at another. The boys slept upstairs. But some of us had found friends in whose rooms we studied and often spent the night. Uncle Ponnu had been given a tiny room created by using a wooden partition just at the main entrance in front of the staircase. There was just enough space for father's bicycle in the gully between the staircase and the wall. It was, in fact, an experiment in living together, sharing and understanding.

My father was posted as the doctor in charge of the government dispensary at Nazarbad, a locality close to the Chamundi hill, the last posting in his service. He used to peddle all the way on his bicycle for work. The house was not witness to any major family events in the years we lived in it. The only bizarre incident I remember about the house is how a crafty ‘guru' managed to convince my pious mother about his spiritual attainments and spent a few days living with us performing elaborate rituals and promising good luck to the family.

The guru was an attractive personality. He looked quite spectacular in his flowing saffron robes. When he propounded some philosophical truth in his deep voice, the ladies would melt and sigh. One day, while the pujas continued, it was discovered that a gold ornament with which the deity had been bedecked, was missing. This resulted in much commotion with the guru assuring everyone that he would get it back using his occult powers. While my mother and others were more than convinced with his assurance, somehow, some of us suspected foul play. The following day, when the guru was busy with the rituals, I went upstairs to the living room, where the guru used to sleep and conducted a quiet search of his personal effects. Lo and behold! I found the ornament.

After the puja and the elaborate lunch that followed, I quietly shared the news of my discovery with my mother. I don't know what she did thereafter\; the old fox had stealthily bolted away by the time we returned home in the evening. Not many knew what had happened. My father, generally given to loud outbursts in situations such as this, had not uttered a word. My mother was not in the least fazed by the incident. To curious queries, as usual, she had an evasive answer: "Who knows what happens in the minds of gurus!" I admire the way my mother, a great diplomat, handled the case. Thereafter, all was quiet and life went on as usual.

I feel it is necessary to delve in some detail about the number of children that constituted our family at one time. My father, a doctor, didn't think that small was beautiful. My mother just loved children and spent most of her life in bringing up kids. On a rough calculation, she must have been in a state of pregnancy for over thirteen years of her life. By the time the family settled in Mysore, we were fifteen: eleven sons and four daughters. My mother gave birth to totally 18 children\; three of them died even before they were a year old. Of the fifteen, only Satyan, the eldest, stayed out because he got a job in Bangalore. The rest were with the parents in the Mysore home pursuing their studies. Someone said that the most important thing a father could do for his children was to love their mother. My father did love my mother like no one ever did. She lived up to 85.

She had a remarkable ability to run the family on meagre resources. The money that came in from father's salary was certainly insufficient. There were no servants. We never felt that we were underfed or impoverished. She had a unique knack of making use of the labour force available at home to get all kinds of work done. Everyone had a specific job to do.

This reminds me of an enjoyable errand mother gave all of us one day. We noticed well dressed palace musicians and drummers were leading a beautifully decorated bullock cart on the 100-feet Road loaded with bags full of sugar for distribution among the people in celebration of the birth of a baby (Gayatri Devi, 1946) to the royal couple. People were vying with one another to receive the royal gift. In a jiffy, we were on the road with whatever containers we were able to find chasing the cart and brought home a lot of sugar. The entire operation was directed by my mother, who stood at the door collecting the bounty in a gunny bag. She even egged some of us to do more than one trip in a relay which we did happily. In the end we had brought in a sizeable quantity of sugar.

Fifth Son, Seventh Child

I was number seven in a family that became fifteen, eleven sons and four daughters. If all the eleven of us had played cricket as a team, I would have been a middle order batsman. If not a batsman or a bowler, I know for sure, I would have been a fielder. This is because I had to do a lot of running about to fetch things for mother and do a number of chores at home because of being born in the middle. Satyan and Raja, the first two children, had everything they wanted. They were precious. By the time I came in, the thrill of having children had been dulled by surfeit. We were too many. Even the last born had a certain advantage. Due care had to be taken so that he was not neglected. But my immediate elder brother Jagga and I, being born in the middle, fell into the ‘also ran' category.

With father approaching his retirement, money became scarce. There were many mouths to feed\; more children to educate. Most of us were in school or college. Raja, the second brother, had decided to do medicine in the Mysore Medical College, an expensive course. The parents felt the pressure. There were no servants. Jagga and I had to do all the household chores like fetching the monthly ration and kerosene from the ration shop, washing clothes and even bringing firewood from the shop. This left us with very little time to study.

The Maharaja's High School was a very prestigious institution. The building was very impressive with the college oval ground behind to play. Every year the school bagged a number of prizes with a large percentage of students passing with distinction. Initially, I found it hard to make friends\; after all I was a newcomer to the class. First I started sitting in one of the back rows generally occupied by the dull company.

A huge fellow, handsome and well dressed, whom even some of the teachers feared, sat in one of those benches. On my first day, as I entered, he beckoned me to sit next to him. He was Sanath Kumar, son of a leading industrialist of the city. He came to school every day sporting his green Raleigh bicycle\; his coat pocket bulging with cash and sometimes with a packet of Gold Flake cigarettes. The front bench boys kept a safe distance from him. It took a few days for me to observe and gather all the dope about him. He was looked upon by the students and the teachers as an insufferable thug. Thinking that discretion was better part of velour, I thought it would be in my interest to cultivate him and remain on his right side.

English Teacher

It took some time for the teachers to notice my presence. I was among the two or three freshers in the class. The first to look at me with some interest was the English teacher, Syed Ebrahim (‘S.I.' as he was called), who was also our Class Teacher. He appeared a cultivated person\; tall, well-built and impressive with his conspicuous headgear- a maroon fez with black tassels. The cane he carried, while in school, didn't fit in well with his personality. He carried it only for effect, never used it. One day, he read out a bombastic paragraph from the English text book and asked any of us in the class to put it in simple English. There was no response. He repeated the query. I stood up and easily rendered the paragraph in simple sentences. "What is your name?" he asked. When I answered, he said "good" and added that he would call me just "TS". He urged me to come forward and sit on one of the front benches which I did with some reluctance. (Editor's note: A detailed story about S.I. written by M. P. V. Shenoi is presented in A Memorable Mix of Grammar and Football.)

I felt a trifle uncomfortable sitting next to those who had built up a reputation as being front bench students. Among them were Shenoi, Rangarajan, Muralidhara Kamath, Ramachandra Rao and Hayagrivachar. It didn't take much time for me to get close to them. Some of them became lifelong friends and did very well in life. Shenoi joined the defence services and retired as Deputy Director General of Military Engineering Service. Rangarajan retired as Chief Engineer of the New Mangalore Port and became an accomplished classical musician. In later life, he came closer to me by marrying my wife's sister. Both Shenoi and Rangarajan have settled in Bangalore. We meet occasionally. Shenoi now looks very impressive with his grey hair and a generous moustache under his nose. (Editor's note: Mr. Shenoi has contributed a number of his memories to this website.) He looks like the younger brother of Lal Krishna Advani, the BJP leader. I have lost contact with Kamath and Ramachandra Rao. But Hayagrivachar, I am told, became a Professor of English in some University and retired.

Among other popular teachers were S.H. Manjaiah (Algebra), Prameshwaran (Physics), Raja Rao (Geography) and Raja Iyengar, the Biology teacher. We always looked forward to the weekly biology practical class, which Raja Iyengar conducted with great interest. One day, to teach us about the human digestive system, he pulled out from a bag, much to our horror, slimy intestines of a sheep which he had collected from a local butcher's shop. The sight was so repulsive to some of us that whenever we saw a sheep on the road we thought of Raja Iyengar.

Though the time I spent in Maharaja's High School was brief, just a year, it was an excellent learning time, joyful and memorable. On the last day, before the school closed for the SSLC examination, Syed Ibrahim gave an emotional lecture. He laid great stress on the importance of education for success in life and urged us to strive hard to become upright individuals. I still remember the words with which he ended his lecture. "You should be like a tuned Veena which, even if a playful child strums the strings, produces only correct notes."

I passed the matriculation examination with distinction standing first in English in the entire State. Syed Ibrahim was delighted. Back home, it was different. My parents were not the kind who worried about their children doing well in studies. They simply assumed that we would do well. I went home after seeing the examination results on the board at school, and broke the news to my mother. All that she said was: "Go in and prostrate before God." My father's reaction was more muted. He said nothing but took out his purse and gave me five rupees (a lot of money then) and suggested that I buy a pair of slippers. I was not disappointed, but thrilled at the prospect of getting a pair of footwear from the famous cobbler in the city market. He had specialized in making slippers using old car tyres for soles. I had no footwear. I went to school dressed in a white pyjama and shirt. I had two pairs of this dress\; I would wear one and wash the other.

© T.S. Nagarajan 2012

Add new comment