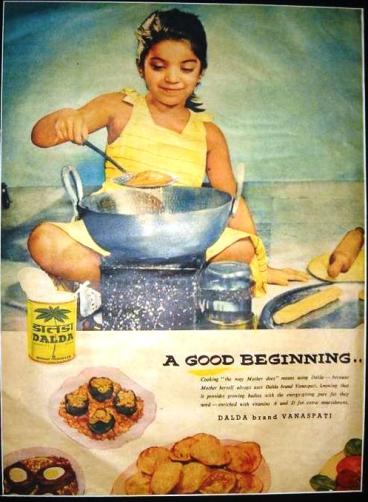

How Dalda mesmerised us in the 1940s

Category:

Shenoi, a civil engineer and MBA, rose to the rank of Deputy Director-General of Works in the Indian Defence Service of Engineers. He has also been a member of HUDCO’s advisory board and of the planning team for Navi Mumbai. After retirement he has been helping NGOs in employment-oriented training, writing articles related to all aspects of housing, urban settlements, infrastructure, project and facility management and advising several companies on these issues. His email id is mpvshanoi@gmail.com.

Introduction to Dalda - 1940s

In the early 1940s, my family lived in Mysore in a complex known colloquially as Nanju Malige (shops built by Nanju).

Nanju, a wholesale grains merchant, had bought a triangular plot and enclosed it with shops at the front and houses at the back, with a huge open area serving as inner court. One road defining the triangular plot was a macadam (non-tarred) highway leading to Manandavady in Kerala, which was known for the tropical forests surrounding it and the forest produce such as timber and honey. The other was a new tarred road from the city to Chamundipuram, leading ultimately to Chamundi hill.

In the evenings, the local children, particularly the poorer children including me, used to play Chiini kolu, which was popular because it did not require any costly equipment, as in cricket or tennis. Editor’s note: Chiini Kolu is similar to Gilli Danda, which is common in northern India. A version of this game can be seen at http://bit.ly/oWD1Gu. Chiini kolu required just two pieces of wood. One piece was round, about 12-15 inches long, and 1-1.5 inch in diameter. The other piece was also round, about 4 inches long, and 1 inch in diameter. It was tapered to sharp points at both ends.

Chiini kolu could be played on any open ground of any shape and any condition. A group of boys would dig a small shallow hole, and place the smaller piece over it. A player would strike one end of the smaller piece with the longer piece. When the smaller piece rose up, the player hit it with all his might. If an opponent caught the piece it as it flew, the player was declared out. If the flying piece was not caught, we would measure the lengths of the longer piece up to the place where the shorter piece lay on the ground. This was the number of runs scored by the player. The more runs you scored, the higher your team’s score. For us it had all the excitement of cricket – with none of the cost.

One evening in 1942 (or perhaps 1943), when other children and I were playing Chiini kolu in the open field around the municipal primary school, suddenly the busy, dusty Nunju Malige road junction became more interesting for us. A smartly decorated small truck drove up the junction, and a man dressed in white got down from the driver’s side. From the other side, an equally well-dressed teenage boy got down – he was the cleaner. The driver and the cleaner walked to the rear of the truck. That is when we stopped our play. Something was happening. A decorated truck, with a well-dressed driver and cleaner – this was not common in our area. To the contrary, our field was a parking and resting place of bullock carts, bullocks and the farmers who drove them.

The two newcomers pulled out a large steel table from the truck, and rested it some distance away. Then they brought down assorted items of things and, placed them one by one on the table. We saw there was a gramophone with its big loudspeaker. This was assembled. Some records were picked up. One of them was placed on it. The gramophone was wound up, and the needle placed in the right position. The instrument started playing the latest movie song. Now, there was no way we could go back to playing Chiini kolu. There was too much going on near the truck and we sure were not going to miss it.

As we crowded around the truck, the driver person assembled a primus stove. One of the older boys in our group went round the truck, and read out loudly what was written on it. It was something like, “Miracle magic ghee, golden, grainy no odour, better taste, Dalda vanaspati, made from vegetable oil, makes delicious eatable.” It ended in bold letters – Lever Brothers. It did not make any sense to us. But none of us made any move to go back to play.

The cleaner set a Dalda tin and containers filled with besun flour, some vegetables, onions, coriander, etc., around the stove. He chopped the onions, cut the vegetables into small pieces, mixed them into the besun, and added coriander to the mix. Then the two of them stopped working – they just stood by, waiting. As the wait became longer, we were all becoming impatient. Then a chotte (colloquial word for Anglo–Indian) arrived on a motorcycle with an assistant. Both got down and inspected the arrangements. A crowd gathered – something was surely going to happen now.

The chotte gave an order. Right away, the driver of the truck placed a frying pan on the stove, put some Dalda into the pan, and lit the stove. Within minutes, he began making pakoras and frying them in Dalda. Once the pakoras were ready, the chotte spoke in Kannada, “This is a new kind of ghee. It does not smell like the oil you use. It makes an excellent frying medium. Things fried in Dalda do not have a smelly taste – they taste just like fried in ghee. Taste and see for yourselves.” The pakoras were distributed among us boys. We ate them eagerly. For sure, they did not smell like the foodstuff fried in unrefined groundnut oil, which was the frying medium in most of our houses, mostly obtained from traditional oil sellers running bullock driven wooden extractors.

A small group of elders also gathered. The chotte repeated what he had said earlier. He added that Dalda costs as much as oil only – less than ghee. But, things fried in Dalda were as good as those made with ghee were. The crowd ate the remaining pakoras and Bajjis.

I told my mother about this incident when I went back home. She was interested and told me to bring some samples next time if the Dalda people came again. Our family had an unusual problem with frying oil. My family had migrated to Mysore from South Kanara where cooking medium was coconut oil. The cooking medium in Mysore was mainly groundnut oil and to some extent sesame oil, both of which were not to her taste. But getting good coconut oil in Mysore was difficult and expensive. So, she was searching for an affordable, tasty alternative to groundnut oil.

A week later, the Dalda group returned with a couple of more hands. This time they had brought a saxophone player. Two of them sang a song, praising the quality of Dalda, calling it a new cooking medium, which gave extraordinary taste and new wholly refreshing experience of both cooking and eating. I remember the theme lines, repeated at the end of each stanza, of the song were:

Dharani yolage namma jayavu

Dalda vanspati yu

(In the world the victory is ours

That is of Dalda vanaspati)

I remember only fragments of the stanzas - they were something like:

Ruchi ruchi pakora, sihi sihi kajjaya

Nentara mechige adipaya, etc., etc.

(Tasty, tasty pakoras, sweet, sweet kajjayas

Guests appreciation etc., etc.)

Some of the Dalda team would sing this loudly, and go round distributing the day's preparation while the saxophone man played in the background.

This time they also distributed small quantities of Dalda wrapped in oilpaper. The packet I got I carried and handed over to my mother. She tried it next day and liked it.

This marketing demonstration went on infrequently for several weeks, sometimes with the free sample of Lifebuoy soap added. Later, they sold some 1 kg or smaller tins of Dalda. Sometimes they distributed small paper flags and whistles to us children. These we carried for days together, and used them in our march through streets, singing the tune when we wanted to mimic the Dalda demonstration.

To us children the whole campaign was great fun. Our families were poor, and we were starved of even two square meals a day. This bonanza of pakoras, bondas, sweets, upma, etc. was really a welcome meal. Whenever the Dalda van appeared, we would shout “Dalda!” run to the van and start singing “… Dalda vanaspati yu” even without anyone’s prompting. We were sad when the campaign ended, but we kept on humming the Dalda tune for some months.

Later years

Dalda went on to mesmerise a whole generation. True to its tune, Dalda went on to conquer the hearts of the Indian middle class, and became the primary medium of everyday cooking or at least on important occasions. Ultimately, Dalda became a generic name for any brand of hydrogenated vegetable oil sold in India.

In the 1970s, a doctor told me that hydrogenated oil is not good for the heart because it has transfats, which tends to clog the arteries. By that time refined oils were available in the market. Smell was no longer a problem. Saffola, an oil without transfats, had appeared in the market. We switched over. Many others might have also switched. Dalda's popularity started to decline.

In the early 2000s, Hindustan Levers sold the brand name and product to some other company. But the tune as well as the entire roadside scene has remained in my memory permanently etched. I think it was one of the early successful marketing campaigns taking the advertising directly to potential consumers, with children playing a key role as influencers.

© M P V Shenoi 2011

Add new comment