Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

A Time of Wonder

Category:

Vijay is a theatre educator. He has been a life member of Bangalore Little Theatre (BLT) since its inception in 1960. He has written over 30 plays, produced widely in India and abroad. In addition, he has adapted and translated several Indian plays into English. By professional training, Vijay is a psychologist and behavioural scientist, and has vast experience in management consultancy, policy research and training in the areas of Organization and Institutional Development..

It was Platform No. 1 of Allahabad Junction on the East Indian Railway. The year must have been 1945.

"Hello, sonny, want a bite of chocolate?" It was a Tommy (a British soldier), seated on a wooden crate, a kit bag next to him and a great big smile on his face. Which little boy of six would decline a chunk of chocolate? A fat bar of dark chocolate in a black wrapper with silver lettering. "Hard rations", the Tommy explained, offering the whole bar if I cared to have it. He had lots more in the kit bag, he explained. I shook my head, not able to make conversation in English, but taking a piece anyway from the bar held out.

I must have run all the way home in excitement. What a delicious piece of chocolate! What a wonderful man, whoever he was, whatever he was doing there! Ours not to reason why! My mother did not share my excitement. Her first reaction was an earnest admonishment. "NEVER take anything to eat from a stranger! Haven't I told you that a hundred times?" She was going to report the misconduct to my father as soon as he returned from a house call he was making. But he was such a nice man, I protested. A rule is a rule, was her standard response. Something about her voice seemed to say it was not a great offence, and that I would come out of it unscathed.

Platform No. 1 had lots of Tommies all the time. I often took a walk there in the evening. The railway station was just behind our home, the quarters provided to my father, serving as Assistant Medical Officer in the Railway. Next to the bungalow was the Railway Institute. Lots of Tommies there too. It was as if they had taken over the whole railway colony.

They had, actually. Allahabad was a key junction in the troop movements to the Burma and Eastern fronts in the war. It was a time of great anxiety for the grown-ups all around me. As I learned a year or two later, for them it was not just about a war being fought in distant lands, it had something to do with our own land, and its freedom from the British. So, were the Tommies our friends or enemies? The grown-ups didn't seem to have an answer to the question. It could only be a time of great wonder for boys like me. Who understood wars? A world war at that.

Suddenly it was all over. Nobody told me the end was coming! There were Tommies in the streets, singing and dancing. They were joined by as many Allahabadis as the street could take. There was much drinking and hugging and kissing and merry making. I was allowed up to the gate to watch. After a while, with my father as escort, we went as far as the Railway Institute to partake of the celebration. The fireworks began. I was allowed to stay up far beyond the regular bedtime. It was a wondrous night.

The next morning the newspaper had headlines the size of which I had never ever seen. Coming to think of it, I don't think I have seen headlines of that size ever again. VICTORY, it said. Each letter could fill one page of my notebook. On the left side of the front page were the flags of the Allies. I learned that day the flags of five nations! The image of that front page was embedded in my brain forever. I would remember the one-word headline and the flags all my life as vividly as on that morning at the end of the war.

Sixty-six years later on a visit to Los Alamos, I found myself in the ranch house in which the scientists embarking on the Manhattan Project first lived. One of the exhibits was a copy of the newspaper that announced the end of the war. I stood transfixed and immobile at the exhibit. It was the very image stored in my brain. VICTORY, with the five flags on one side. It was unbelievable. It was a wondrous revisitation.

* * * * *

Once again, in the 1940s, the townsfolk of Allahabad were out on the streets. Once again it was the air of jubilation. It was late at night too. The family drove to a street where the old box model Ford could be parked to a side and then walked down to where the action seemed to be. Where the narrow lane opened up to the main road, it was all colour, all noise, and all senses were awakened. There were impromptu bands assembled here and there, groups shouting slogans in chorus, hordes thronging both sides of the road and all the balconies on both sides and all the rooftops. They were singing, waving flags, distributing sweets. The painted banners had the familiar smiling face of Jawaharlal Nehru, fondly called Panditji by all. Some had Gandhi thrown in for good measure. The family made its way to the first floor balcony of a home that had reserved the space for us. I was then told that the road led to the jail where Nehru had been imprisoned, and from where he was soon to emerge a free man.

For some time it looked as if it was a gathering at a wedding to which the whole of Allahabad had been invited. Everybody seemed very happy about something, but not quite paying attention to it. The night was endless, nobody was in a hurry to get home. And then ... a distinct roar of jubilant voices was heard at one end of the road, sweeping down in waves towards the spot we had occupied.

The moment had arrived.

In the distance we could see a large convertible car, the top opened, cruising down as if it was a baarat (wedding party) carrying a bridegroom, petromax lanterns on either side, flowers tossed on it from all sides. Standing in the car, smiling, hands pressed together in namaskar was the man himself, the one they were all talking about, the man who should be the leader of the nation awaiting its rebirth.

The process of the transfer of power had begun. I wonder now how many in the gathering that night might have been aware of the machinations that had already begun in the back room. It would be a painfully protracted period of wrangling before the darling son of Allahabad would be proclaimed the chosen leader. And there was a heavy price to be paid for the gift of India's Independence.

* * * * *

1947. There were rivers of blood on the streets of Allahabad. People talked about rotting corpses and dogs marking their territories around them. The city had not known rioting and communal frenzy of such magnitude. Us and Them, Our land and Your land, Our gods and Yours, our daggers and your choppers - it was all so confusing. How could it be? It seemed so wildly unjust for an eight year old to see bloodshed on the streets of a town that had so recently hosted two magnificent celebrations with such gusto. Where was the communal hatred then? How did it spring up now, all so suddenly? What was it all about?

The killing and the burning and the looting had stopped. The protracted curfew seemed to be working. But it was stifling. We were allowed to water the flowers in the garden but not allowed an inch outside the compound gate. The stillness all along South Road was deathly. And frightening. Not a soul in sight except the occasional band of heavily armed patrolmen. The only civilian car we saw on the road was my father's. He had the required permit to drive to the hospital and to make house calls. He and the car were known well enough to be let through.

The call for a house visit came late in the evening. It was a family in a Muslim mohalla. The woman had very high fever and was delirious. The family, like many others in the mohalla, trusted my father instinctly. He simply had to go. When the car left the compound, an overpowering dread descended on the household. The wait seemed endless. Why the gloom, I wondered. He had been on house calls before, hadn't he? My father was a doctor!

On his return, he told us about the extremely respectful and courteous treatment received from the entire neighbourhood of the sick woman. There was not a trace of hostility or rancour. The pervading warmth was genuine, not put on for the benefit of medication. Knowing well that that not all in the city might feel the same way, a group of bodyguards had been posted at the entrance to the mohalla to escort my father to the house and escort him back.

* * * * *

Early in 1948, the family moved to the railway town of Jamalpur, a satellite of Monghyr town in Bihar. Jamalpur had the renowned railway workshop and the prestigious finishing school for officers joining the railway service - a sort of IAS cadre for the railways. It was a promotion for my father. He was now the Medical Officer for the entire railway township.

I was put into the Railway School run by East Indian Railway. It was a proper English school, with English teachers and an English curriculum. I did not speak a word of English. My medium of instruction in Allahabad had been Hindi. Jamalpur was a nice place, with a lovely Railway Institute (Club) and a good school. We lived in a comfortable bungalow, complete with a lovely lychee tree. But I could not speak English! How was I going to cope with this new world? How much more complicated could life get? I was soon to find out.

January 30, 1948. We were sitting in the verandah. The radio was on in the living room. The programme was interrupted and the announcement was made. Mahatma Gandhi was no more. Almost immediately, the sarangi music was put on. It was sarangi the whole evening and night, with the occasional break to repeat the announcement and the circumstances of his death and the aftermath, as they appeared clearer by the hour.

Who would want to kill this gentle, god fearing, kindly old man? Why? What madness had possessed people of this country? First the communal frenzy, now this! What was happening? Nobody had an answer.

It felt like only yesterday that we had all gone to the railway station to meet the train in which he was travelling. From where, to where, we did not know, but he was on that train. He stood at the doorway of the Third Class compartment, palms pressed in a namaste, smiling, the most beautifully serene face on the most emaciated body I had ever seen. So, this was the man, I thought, the man the whole world admires and reveres. Why was he travelling Third Class? My father could easily have provided him an Officer's Saloon. That smile! It seemed to be saying something. I wished I knew what it was.

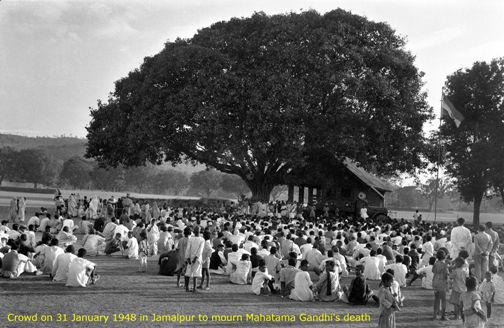

The next day was another occasion for the townsfolk to gather in public again. All of Jamalpur congregated at the peepal tree in the centre of the huge maidan with Kali-pahad forming the distant panoramic backdrop. .

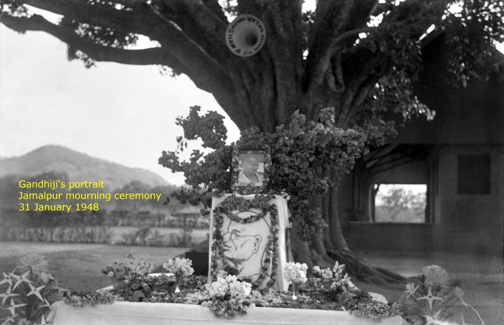

At the base of the tree was a hastily drawn and framed picture of the Mahatma’s face. Smiling.

© Vijay Padaki 2011

Comments

Add new comment