Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Papaji's Inspiration

Category:

Valarie is a writer, filmmaker, and lecturer who has become a brave new voice on race and religion, hate and healing in post-Sept 11th America. A third-generation Sikh American, Valarie wrote and produced the critically acclaimed documentary film Divided We Fall (2008), which chronicles hate violence in the US after Sept 11, 2001. She earned bachelor's degrees in religion and international relations at Stanford University, master's in theological studies at Harvard Divinity School, and is now a student at Yale Law School.

Editor's note: This is a slightly edited version of an article on the author's blog. http://valariekaur.blogspot.com/2008/11/papa-jis-funeral.html

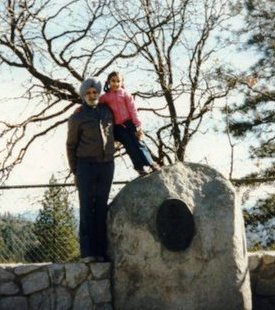

Papa Ji was my mother's father. His wisdom and love made me who I am - and inspired Divided We Fall.

In November 2008, in California, I stood before his casket adorned with flowers, where his face shone regal in a red turban, and gazed out at a hundred people who had gathered in the small chapel. I never write down what I will say before an audience, but I knew that I needed to draw courage from words on paper. I clutched the pages and spoke through tears:

My Beautiful Papa Ji,

In the beginning, there were sounds: your voice at my childhood bedside, teaching me to recite the root verse of the Guru Granth Sahib:

Ik Onkar, Sat Naam, Karta Purakh, Nirbhau, Nirvair, Akal Murat, Ajuni Saibhang, Gurprashad, Jap. Aad Sach. Jugad Sach. Hai Bhi Sach. Nanak Hosi Bhi Sach.

One, Manifest as Word, True of Name, Creative Being, Without Fear, Without Enmity, Whose Form is Infinite, Unborn, Self-Existent, through the grace of the guru. True in the beginning, True before time began. He is True, Nanak, and ever will be True.

You would tuck me in and kiss me on the forehead and ask: "Happy-happy?" And I was happy. I was happy walking with you to the grocery store for ice-cream cones and running through the back yard as you sprayed us with the hose, the water cascading and sparkling in the summer sun. I was happy watching you carefully wrap my school-books out of brown paper bags or cutting us fresh cantaloupe with utter precision. I was happy handing you my latest poem to tuck away in the file you kept of all my writings and learning how to underline my favorite sentences in books just like you. I was happy running from you when you became the tickle monster, and I was happy jumping into the bed next to you when I was sad. You would stroke my hair and I would gaze at your perfect ivory feet until I fell asleep. You were the pillar of wisdom in my whole existence, my constant companion and my source of truth, my playmate and my teacher.

As I got older, you began telling me stories - stories that would shape my life passions. You told me stories from your childhood - you played at the foot of a great banyan tree in your father's village where Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims and Christians lived side by side.

You told me stories from your service in World War II - you would sleep through the air raids at night because you held faith in what your father told you, "My son, there is no German bullet made for you"\; you refused to take off your turban when you were sent to the frontlines, saying, "God gave me my helmet"\; you humbled your obnoxious British superiors when you outran them on Gaza beaches\; and you wrapped your friend's body with your turban when he was killed next to you. You told me stories about how you escaped India's Partition in 1947 and the anti-Sikh riots of 1984. And when you told me all these stories, you imparted to me a sense of history, a rootedness that bound me to my ancestral home and people, and a deep sense of faith - for if you could maintain complete faith in God as your companion through air raids and illnesses, riots and unspeakable loss, then I could do the same.

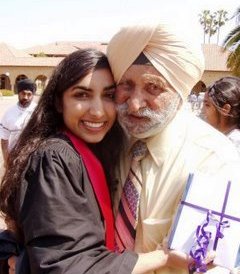

Those early years we spent together - granddaughter and grandfather - made me who I am. You stirred a deep commitment to social justice that set my course of study in religion and ethics and law and inspired me to continue telling stories through speaking and teaching and even through making a film. Do you know, Papa Ji, that thousands of people have met you and learned about Sikhism from you in Divided We Fall? I can just hear you saying, "You have made me great." And you can just hear me saying, "It's the other way around."

In these recent years, as I make my way into adulthood and experience real pain, real disappointment, and real fear for the first time, I begin to understand your magnificence, not just as a grandfather but as a human being who lived and breathed truth even in the face of the worst suffering. You had a small piece of paper taped to your radio by your bedside that read: "ISKCATAUAC." I thought it was a Punjabi word. I didn't know until you revealed that it was an acronym: "I shall keep calm at all times and under all circumstances." And you did. Even when disagreement entered our own relationship, your calm opened into understanding that deepened our bond.

You lived every moment in this deep calm with child-like wonder and love for the beauty in the world - and you cultivated that beauty around you, in the blooming flowers of the garden you kept and in the hearts of your friends and family. Why else would so many visitors - women and men, young and old, rich and poor - flow into your room day after day for your advice, your poetry, and your company? We were inspired by your fierce intellect, your lust for learning, your resourcefulness, your love for life, and your fearlessness - your fearlessness.

Papa Ji, you were never afraid. In the darkest hours of your illness, you were never afraid. When your lungs hardened, your throat closed, and the pain shot through you and rendered you gasping for breath and motionless these last weeks, you still managed to smile at us. You would make us laugh. You showed us you had no fear. We bathed you in our love and your eyes sparkled and your spirit blazed, even as your body shut down.

Four summers ago, I asked you if you were afraid of death:

"Absolutely no," you said. "There is no difference in my being here or not here. If I be, God will be with me. If I don't be, I will be with God... I had been subject to changes from unit to unit in my army service, subject to transfers. And I had been going from place to place happily. On my last transfer also, I'll go happily."

I asked you, "What is your last wish at the time of death?"

"That I should be able to smile with all the people around me present at that time. That I could give a smile to all the people around me. This is the only wish I have. I want to go smiling to my master. Wailing and all that, this is worldly and serves no purpose. It does not do any good. So worldly attachments end. We should accept the end happily."

You died at home, with all your children surrounding you: Masi Auntie, Mama Ji and Mami Auntie, Mommy and Daddy, and Kathy rubbing your feet. They touched your lips with amrit (holy water), and you gave them a smile.

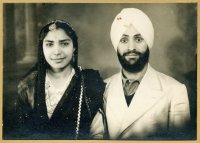

You waited until Mummy Ji (your wife of 62 years) gave you amrit, you took it into your mouth, you sighed, and gazing out, you died. It was miraculous. It was perfect. Your life was a perfect miracle.

I know that you want us to be happy and you would be very upset with all of our wailing. So I must tell you, Papa Ji, that the tears we shed today are not for you. They're not for you! We cry for ourselves. We cry because we will miss you terribly. You have made memories with each of us, and we know that you promised to appear when we summon you - but let us cry for a moment. Let me cry for a moment for what I have lost.

I have lost the pleasure of seeing you walking your garden, hands clasped behind your back, surveying the rows of vegetables like a military captain, the warmth of your face glowing in the sunset.

I have lost the comfort of falling asleep on your shoulder, running my thumb over the smooth end of the nail on your right hand. I have lost the excitement of closing my eyes and sending you images to dream about on Monday nights and hearing you report in the morning. I have lost the joy in hearing you say before some new adventure, "Let's make a memory!"

I have lost the feeling of connection when you calm beneath my hands or when I rub the blue elixir into your forehead and wash you in love. I have lost the tremor of your voice, asking: "Happy-happy?"

No, Papa Ji, I am not happy. Just for a moment, give me permission not to be happy: I have lost my pillar of wisdom, my constant companion, my playmate and my teacher.

Since you died, I have turned into a small girl looking for her grandfather. I wail in the streets just as you instructed me not to, then I sit quietly before a candle listening for you. I walk the cemetery calling out your name and sob when there is no answer. I fly home and search for you in all the rooms of the house. And I stand by your casket - you look handsome and regal like a king but your forehead is icy cold when I kiss it and your chest is hard where I used to rub it and your face is white without the blush of the sun, and I cannot find you there. You are not there either. The small girl in me cries.

But there is another part of me too. Deep inside, where you planted a seed of strength in my heart, I know that you are just on the other side of my anger and grief. I know that you have been with me all along. And you will continue to be with me. You will be within each of your grandchildren whenever we need you: you are laying a hand on Andrea's head, you are dancing inside Ginny's poetry, you are the star guiding Sonny, you are the deep rhythm in Sanjeev, you are the dreams in Neetu, and you live within Jyoti Didi and her son Harry too. It is an honor to be your grandchild\; it is an honor to be blessed with your love.

We will try to live up to your example: your deep faith in God, your constant curiosity, your discipline in mind and body, your endless creativity, and yes, your fearlessness in life and in the face of death. I will feel you in the root of me, so that everything that I do, you do. Everyone who knows me, will know you. My children will know you and their children's children will know you. It's just as you always said: There is nothing that can separate us. There is nothing that can separate those who love one another unconditionally. And so I will go on loving you and talking to you until I am a very old woman.

In that case, since this is not goodbye, we grandchildren have one last prayer to offer your spirit as it goes blazing up into the heart of God. It is the prayer that you taught all of us when you drove us to school each day: Tati vao na lagi.

The hot wind does not even touch one who is under the Protection of God.

On all four sides I am surrounded by God's Circle of Protection\; pain does not afflict me, O Siblings of Destiny.

I have met the Perfect True Guru, who has done this deed.

He has given me the medicine of God's Name, and I enshrine love for the One Lord.

God has saved me, and eradicated all my sickness.

Says Nanak, God has showered me with His Mercy\; He has become my help and support.

[Guru Arjan, SGGS, 819:16]

The hot wind cannot touch you in the fires, Papa Ji, just as it could not touch you in life, because you move in the circle of God's Protection.

Captain Gurdial Singh (March 7, 1921 - November 19, 2008)

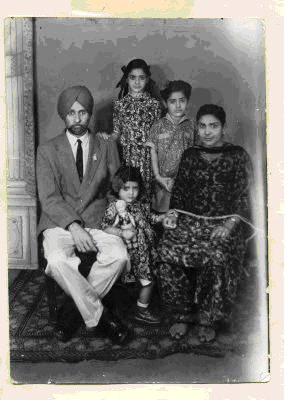

He was born to Tara Singh and Kesar Kaur in the village of Basupanu in Punjab, British India. He spent his childhood playing beneath a great Banyan tree and excelled at the top of his class in mechanics and engineering.

He joined the Indian Army at the age of 18 and fought in World War II, serving in Sudan, Ethiopia, Egypt, Libya, Iraq, Iran, and Palestine. He cheated death several times and escaped the mass riots that consumed India in the 1947 Partition.

After the war, he transferred to Kashmir, Sikkim, Bangalore, and Joshi Math, where the music of the river Ganges stirred new passions in him, and he began to write poetry.

Shortly after he survived the anti-Sikh riots of 1984 in Delhi, Papa Ji immigrated to the United States to live with his daughter Dolly and her family in California.

Here he worked at the office of Senior Citizens, tended a blooming garden, read and wrote fervently, and published three books of poetry in Punjabi, Urdu, and English. His life work in poetry won many honours, including recognition by the Punjabi Literary Society of Fresno and the Punjabi University of Patiala. In 2002, Papa Ji returned to India to rebuild his family's house in Patiala, Punjab, so that his grandchildren would always have a home in their ancestral land.

© Valarie Kaur 2009

Comments

Add new comment