Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

My Father and my Uncles: Revolutionary Freedom Fighters

Category:

Tags:

Surajit Sanyal was born in Calcutta in 1950, and moved within three months to Allahabad, UP. His early years were spent in Allahabad and Gorakhpur, although ancestral roots were in Benaras. He spent most of his adolescence in Jaipur, Rajasthan. A product of St. Xavier’s Jaipur, Maharaja’s College, Jaipur, and St. Xavier’s College, Calcutta, he went on to complete his management studies in XLRI, Jamshedpur. He started his career in advertising in Calcutta in 1975 and subsequently moved to the largest public utility company in the same city. He now leads a retired life in Salt Lake, Kolkata, with his wife Supriti and his son Sudipto.

In July 1995, the Nehru Memorial Library sent me a letter. It said, in part:

"We are publishing the selected works of Acharya Narendra Dev. In a statement Acharyaji has referred to the treatment meted out to your father, Shri Bhupendra Nath Sanyal, by the Agra jail authorities, when he was there in 1941, We want to give his bio-data in the book. Despite our best efforts we could not get his date and place of death, I enclose copy of the bio-data we have prepared, but I am not satisfied with it. His role in our freedom movement was significant."

Letter from Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi. 1995

I wrote a lengthy reply. The rest of this article is based on my letter.

Your letter (I wrote back) triggered a whole lot of memories regarding not only my father, but my uncles as well, and the whole gamut of family relationships during my early years in Allahabad, Delhi, and Jaipur. The trouble is that no mention of my father can be made without reference to my uncles, my cousins, and my father’s friends and colleagues during the freedom movement and thereafter.

My father, Bhupendra Nath Sanyal, was born on 1st January, 1906 in Calcutta, but his early years were never spent there – the family moved to our ancestral home in Madanpura, Benaras, after the death of my grandfather, Hari Nath Sanyal. The immediate family consisted of my grandmother and her four sons, Sachindra Nath, Rabindra Nath, Jitendra Nath, and the youngest, Bhupendra Nath.

My grandfather had been a Chief Accountant of the North West Frontier Railway in the late 19th century and had very close links with exclusively English officers then. It now seems strange to me that all his four sons should have been inspired to become illustrious fighters for India’s freedom.

I shall have to start with my grandmother because no story about these four brothers can be complete without reference to her. She was extraordinary by all accounts, “majestic and beautiful” (reminiscences of Sri J. C. Mukherjee, Ex-Member of Anushilan Samiti of Benares, a secret revolutionary organisation). She always seemed to be burning with passionate patriotism and knew well the dangers connected to the revolutionary (the British would have called it “terrorist”) life. Her only regret seemed to be that she did not have more sons to dedicate to the service of the country.

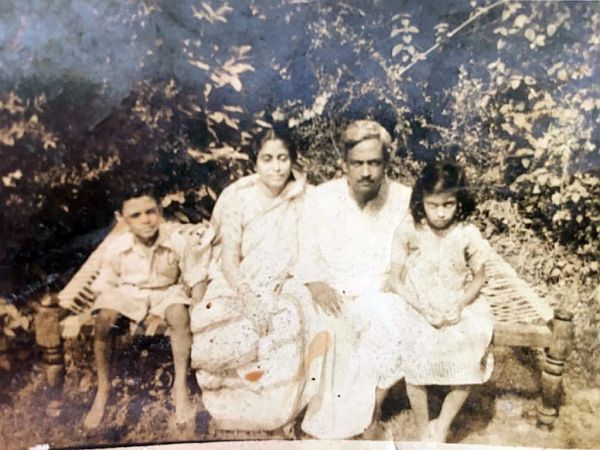

(From L to R) Jitendra Nath Sanyal, Sachindra Nath Sanyal, Rabindra Nath Sanyal and Bhupendra Nath Sanyal

(Children standing, from L) Kanak Sanyal (Bagchi) and Meera Sanyal (Bhattacharya). Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh. Late 1930s.

My eldest uncle, Sachindra Nath Sanyal, was the revolutionary of revolutionaries. A lot has been said and written about him, but only of late. The family is indeed grateful to President Giani Zail Singh for having encouraged us to celebrate his 97th birth anniversary in New Delhi in 1983, which was also attended by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

Sachindra Nath Sanyal.

It is now history that Sachindra Nath spent 25 of his 50 years in various prisons of North India and the Andamans. More than a hundred years ago, in 1915, along with the legendary Rash Behari Bose and other Ghadar Party members, he planned an armed uprising on the lines of the Revolt of 1857 with the help of Indian soldiers of the British Army, then stationed in various parts of North India. The date fixed for the uprising was 19th February, 1915.

Several thousand Sikhs of the Ghadar Party, who had arrived a year ago from America and Canada, were restless in organising a revolution in India. They had no leader. Rash Behari Bose and Sachindra Nath Sanyal mobilised their support. The Sedition Committee Records of that time include a whole lot about this planned revolt. It is not surprising that they prepared a flag with three colours – yellow (Sikh), red (Hindu), and green (Muslim) – and these flags were distributed to all concerned, to be hoisted after a successful action. It is now also a part of history that because of the treachery of one man, the rising did not take place. However, Sir Michael O’Dwyer wrote in his memoirs (India As I Knew It) that one of these flags was claimed and kept by him as a souvenir.

My uncle was one of the very few who had brought together and coordinated the revolutionaries of Bengal, Bihar, United Provinces, and Punjab, and was possibly the main coordinator at around that time and 1915 onwards. In the Benares Conspiracy Case of 1916, Rabindra Nath Sanyal and Jitendra Nath Sanyal, along with Sachindra Nath Sanyal, were arrested. Sachindra Nath was deported and transported for life to the Andamans. My two other uncles, Rabindra Nath and Jitendra Nath, were sentenced to shorter jail terms. Rabindra Nath was himself under internment in Gorakhpur.

In the Andaman Cellular Jail, the prisoners were allowed to write and receive one letter a year.

Page 1 - Letter written by Sachindra Nath Sanyal to Rabindra Nath Sanyal (both uncles of author). 1916

Page 2 - Letter written by Sachindra Nath Sanyal to Rabindra Nath Sanyal (both uncles of author). 1916

Sachindra Nath Sanyal was the Founder President of the Benaras Anushilan Samiti. On account of the general amnesty declared by the British Government after the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms, my uncle was unexpectedly released from the Andamans in 1920. What followed was a long and difficult path during which he went through insufferable times. My uncle gathered together a committed band of people from Bengal, United Provinces, and Punjab to organise a strong united revolutionary party.

During the course of his sojourns, Sachindra Nath met Bhagat Singh at Lahore, introduced to him by the historian Jaychandra Vidyalankar (who taught Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev at Lahore University). My uncle founded, with others, the Hindustan Republican Association, and asked Bhagat Singh to coordinate its activities. The politics and ideology of this party were influenced by the ideas of the October Revolution in Russia.

A printed manifesto titled Revolutionary was issued in January 1925 in the name of Sri Sachindra Nath Sanyal. The Bengal Administrative Report of 1924-25 had a lot to say about the Revolutionary. The purpose of this organisation, as mentioned in this pamphlet, was coincidentally the same as that of the monthly issue of Masses of India, which was founded, edited, and published from abroad by M. N. Roy. Sachindra Nath Sanyal was also arrested in the Lahore Conspiracy Case in 1930, along with Sri Bijoy Sinha, Sri B. K. Dutt, and others.

Sanyal was sentenced to another term of life imprisonment for his lead role in the Kakori Conspiracy Case (more on this case below). Incidentally, his third term of imprisonment – at Naini Central Jail in Allahabad – was cut short when the Congress government in the United Provinces released him and five other prisoners on 24th August, 1937. He was arrested again, for the fourth time, at the time of the Quit India Movement in 1942 under the Defence of India Rules.

Bhagat Singh, V. D. Savarkar, Bhai Parmanand, Pandit Parmanand of Jhansi, Barin Kumar Ghosh (younger brother of Rishi Aurobindo), Upendra Nath Banerjee, and many others were ardent followers of my uncle. Bandi Jeevan, a classic that my uncle wrote, describes a large part of the movement which he often led. Two parts of this book were published in Hindi in the 1930s – the British government did not allow publication of the rest. It was finally published in full, in Bengali, in 2001, and since then has been published in Hindi and Punjabi.

Bandi Jeevan Bengali

Bandi Jeevan Hindi

Bandi Jeevan Punjabi

I now come to my father’s role. With an elder brother like the one described above, it is inconceivable that the other brothers would be left behind in India’s freedom fight.

My father, Bhupendra Nath Sanyal, always believed in a second Mutiny after the first war of Independence in 1857. It was a romantic age in a sense, and patriotism was in his very blood.

His initial conception of Swaraj was deeply influenced by my eldest uncle’s views. He was a pet with his grandmother. I understand, from what my father has written in his book Facets of Indian Politics (a compilation of his articles and speeches), that the Benares house they lived in was her father’s. Her stirring stories to my father spurred him to think that greater achievements were in store for him. Besides, as my father wrote, he could feel his brother conspiring “as so many people would constantly come in and come out and he would see all sorts of weapons stocked in an almirah.”

My father was initially associated with the Hindustan Republican Association, which my uncle founded. This became the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army by the time he was in his university days. He was deeply influenced by the revolutionary movement of Bengal and its accounts by the person he was named after, Dr. Bhupendra Nath Dutta – younger brother of Swami Vivekananda – and he was, of course, inevitably and very naturally influenced by my uncle’s Bandi Jeevan.

He was an avid reader, in his early days in the freedom movement, of the works of Garibaldi, Mazzini, Cavour, the French Revolution, the Russo-Japanese War, and also Dan Breen’s My Fight for Irish Freedom. His mental makeup was also influenced by Mikhail Bakunin; not by his creed of anarchism, but by his life of adventure and privations.

To go back to my father’s early days, he joined an Anglo-Bengali school in Benares, where Sachin Bakshi was his classmate. They would one day become cell-mates in jail after Kakori. He often told me that whenever he went to see his three elder brothers in jail during 1915-1916 (Benaras Conspiracy Case), he wanted to be in jail with them, and my grandmother had once also requested the jail authorities to keep him there for a few hours so that he could feel a bit happy.

Very shortly thereafter, the family shifted to Gorakhpur – where my uncle lived – because it was difficult for my father and grandmother to stay alone in Benaras. My father continued his studies in the Government Jubilee School in Gorakhpur. He was a phenomenal student, and a very good hockey and football player. He was on a government scholarship for his success in school. After his matriculation, the family shifted to Allahabad, where my father joined the B.Sc. course at Ewing Christian College in the University of Allahabad. For the record, Feroze Gandhi was a student at the college at the same time, and the two men became good friends.

By now, the Revolutionary Party was being reorganised. My father took his work among the university students as well as with Sachin Bakshi and Krishna Kant Malaviya, who was then a noted Congressman from Allahabad. When he was in the third year of B.Sc., he sent a fellow student and member of the Revolutionary Party with a chit to Lucknow to meet Govinda Karan, a revolutionary who was convicted in the Benaras Conspiracy Case. Since my father had signed his full name, he had to face police interrogation.

In 1923, my father was arrested and sent to prison. He has described in detail his experiences in a police lock-up, when he was awaiting the trial and sent to Allahabad District Jail, in Joys and Sorrows Behind Prison Bars (which was first printed in The People, Lahore. A copy was recently tracked down at the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Smarak Trust in New Delhi, but the Covid pandemic has prevented me from getting hold of it). He was then sent to Lucknow from Allahabad District Jail along with Sachindra Nath Sanyal, but separately. Handcuffed, he was conveyed to the nearest railway station in a carriage. Early next morning, he was in Lucknow Jail, where my uncle, Sachindra Nath Sanyal, had also come to stand trial. The brothers talked behind gratings.

Kakori was a place some distance away from Lucknow. My father and my eldest uncle had planned to rob arms from a train at Kakori. The Kakori case was masterminded by Sachindra Nath Sanyal, who was sentenced to life imprisonment in the Cellular Jail in the Andamans on account of it.

The trial courtroom, as described by my father, was full of police and C.I.D., all armed with tense expectation. The prisoners were stunned for a while as the sentences were handed down but regained their composure shortly. Judge Hamilton’s verdict was cruel. On 16th April, 1927, it sealed the fates of Thakur Roshan Singh, Ram Prasad Bismil, Rajendra Nath Lahiri, and Ashfaqulla, who were hanged in the Naini Central Jail, Allahabad.

October 22 is the birthday of Ashfaqulla. In part, his birthday triggered in me an urge to write this article.

My father was sentenced to seven years in prison in the Kakori Conspiracy case.

A group photograph of the prisoners in the Kakori Case, after they were sentenced by Judge Hamilton, in Lucknow in 1927. In the front row, my uncle is number 15, and my father is number 16.

My father later talked to me about this and told me that he held these four in the highest regard. He was with them till the wee hours of the morning, when they were separated, and he said that he saw only courage on the faces of these four men. There were many others like Jogesh Chatterjee, Prem Kishan Khanna (both of these gentlemen later became Members of Parliament), Vishnu Charan Dublish, Suresh Bhattacharjee, Manmath Nath Gupta, and others

After the customary photograph, they were separated into different groups. The same night, they were transferred to different jails. My father was fortunate to meet Rajendra Lahiri at the railway station. His dauntless figure haunted my father for a long time. They parted company at Bara Banki. He could not believe he was seeing Lahiri for the last time (I have mentioned earlier that Rajendra Lahiri was hanged). At two in the morning, my father got off at Faizabad, full of the memory of all his Kakori teammates and under-trial cell-mates; he found himself deep within the high walls of Faizabad Jail. He had stepped into the trail-blazing ways of Sachindra Nath, Rabindra Nath, and Jitendra Nath Sanyal, and was on the threshold of terrorist life.

Life in prison was terrible, and the less said, the better. British officers then used to extracting more labour than was prescribed did not spare the rod. My father has described life in prison in fair detail in Joys and Sorrows.

After a year’s stay in Faizabad, some officers were transferred, and an Indian Civil Surgeon took charge of the jail. As long as he remained in charge, prisoners, in general, received more humane treatment than either before or after. But my father was transferred to the habitual ward from the political ward, to live with “habitual criminals” – it was an eye-opener to him to see this group being treated much better than political prisoners, with more skills being imparted to them.

Bhupendra Nath was accused of smuggling out letters from Faizabad Jail and faced a jail court-martial. He was given solitary confinement for some months. He pored over books (which were supplied) and also learnt the Holy Quran by heart during this time from his guard, who was the only human contact he had.

The last six months of the above term were spent at Naini Central Prison. I have never visited Faizabad District Jail, but he had told me that five such jails as Faizabad could be made out to form the Naini Central Prison.

In 1932, he was released. However, after two and a half months of liberty, he found himself again in prison. He was arrested in Kanpur on the charge of having shot at two constables, and had to stand in the line-up at the identification parade. Fortunately, nobody could identify him; let out on bail, he was again free after nearly six months.

While in prison, he had learnt of the Naujawan Bharat Sabha, an organisation created by Bhagat Singh under the guidance of Sachindra Nath Sanyal. Soon after his release, he joined this organisation.

Meanwhile, he had also joined the Indian National Congress, and was elected to the Provincial Committee, and then to the highest body, the AICC, along with Subhas Chandra Bose, a person he had got close to. At the first All-India Session of the Naujawan Bharat Sabha, he was one of the most forceful speakers, along with Bose and Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya. In his book Facets of Indian Politics, my father writes how, at one stage, the Communist faction kept interrupting Malaviya’s speech. Bose and my father repeatedly requested them to let Malaviya have his say.

By 1936, my father was regarded as a front-ranking leader in the Congress. At the time, “Congress activity was characterized by generally cordial relations between the Congress Left and Right,” writes Visalakshi Menon in From Movement To Government: The Congress in the United Provinces, 1937-42. “At an Allahabad Town Congress Committee meeting [in 1938] a confirmed right-winger like J.B. Kripalani could speak along with the ex-terrorist Bhupendra Nath Sanyal and a Congress Socialist like Ram Manohar Lohia in support of Sachindra Nath Bakshi’s hunger-strike. At the third session of the Eastern India Railwaymen’s Conference held in Lucknow from 12-14 June, C.B. Gupta, as well as Mohanlal Saksena, played an active role, besides Socialists like Acharya Narendra Dev and Communists like Sant Singh Yusuf (Menon, 70).

It was then that he came close to a controversial figure – M.N. Roy. As a consequence, many of my father’s followers rallied around Roy.

A word about M.N. Roy. Born Narendra Nath Bhattacharya, Roy was a revolutionary, activist, and political philosopher who had, in 1917, founded the first Communist party outside Russia, the Socialist Workers’ Party of Mexico. “Many Indian nationalists, including Roy, became convinced that only an armed struggle against the British Raj would be sufficient to separate India from the British empire” (Wikipedia 2020). He served over five years for the Indian freedom movement in five different jails. For a brief period, my father was associated actively with Roy’s Radical Humanist movement; he served as Assistant Editor of the movement’s mouthpiece, The Radical Humanist. However, in the mainstream Congress later, he gradually drifted towards Subhas Chandra Bose.

M. N. Roy (seated middle), his wife Ellen Gottschalk (seated second from right)

Bhupendra Nath Sanyal (standing middle)

My father had opposed the Congress’s participation in the Provincial Ministry in 1937, and his fiery speech in this connection at the Delhi Congress Convention was extensively quoted in the press then. At the Tripuri Congress Convention in 1939, Sanyal staunchly supported Subhas Bose, who was being opposed by the right-wingers in the party. It bears mention here that he did not, however, join the Forward Bloc when it was founded by Bose that same year.

My father’s participation and oratory at the Ramgarh Congress Convention (1940) were memorable, as gathered from my father’s fellow revolutionaries, whom I met in Lucknow and Delhi years later. Even Dr. Rajendra Prasad (the convention’s Guest of Honour), in his speech, agreed with my father that a national revolution during that period was possible only through two ways – Mahatma Gandhi’s and M. N. Roy’s. (An interesting aside: Maulana Abul Kamal Azad was elected Congress President at this convention).

It is interesting to note that, at a meeting of the Provincial Committee of the INC, my father had a wordy duel with Pandit Nehru when the latter was speaking both for and against socialism. My father had then said, “Undigested communism was harmful; that nowadays it has become a fashion to speak of communism without caring to learn what it really is” (Bhupendra Nath Sanyal, Facets of Indian Politics). Nehru had taken it personally for that moment, and had remarked, probably as rebuke and in a different context, that, “I do not think the speaker is wearing khaddar.”

My father had retorted that he was wearing khaddar, and that he was not one of those men who discard their dresses as soon as they cross the Mediterranean. This was, of course, a reference to Nehru’s donning European attire on his visit to Spain, and it drew loud applause from the assembly. In retrospect, I find it amusing, since, on my visits to Delhi with my father in the post-Independence era, I found both of them drawn fairly close to each other. (These visits were during our days in Jaipur, Rajasthan, in the 1960s).

During the provincial meeting of the Naujawan Bharat Sabha (see above) in Mathura in 1931, my father was entrusted personally by Subhas Chandra Bose with presiding over and conducting the meeting, since the latter was unable to attend. As S.K. Mittal and Irfan Habib point out, “It is significant that along with British imperialism it wanted to see the end of other imperialisms also. The Sabha movement had a wider perspective; it believed in the freedom of other enslaved nations also” (S. K. Mittal and Irfan Habib, “Towards Independence and Socialist Republic: Naujawan Bharat Sabha: Part One,” Social Scientist Vol. 8, No. 2, September, 1979, p. 20).

As evidence of this “wider perspective,” the authors cite my father’s speech of May 22, 1931, where he said: “If any atrocities are perpetuated on them (China, Kabul and others) and the army of our country goes there to fire at and annihilate the people there, it is a matter of great shame that we cannot check it. We shall have to check it and ask the people of our country not to go to other countries which have got no struggle with our country, to fire at and kill them and enslave the innocent people there” (National Archives of India file 27/5/1931, in Mittal and Habib, p. 27).

At the same meeting, Bhupendra Nath ridiculed the idea of dominion status within the Empire and advocated complete Independence. This led to his conviction for sedition (3 years’ rigorous imprisonment), and he was first sent to Fatehgarh Central Jail and thereon to Agra Central Jail. This is where he was in touch with Jawaharlal Nehru and Acharya Narendra Dev, who were both serving sentences. Dev, whose mention of my father triggered this set of memories, had a deeply spiritual and political influence on my father in jail.

The Agra Central Jail was a very hard experience for my father. Later, he used to tell me frequently how exceedingly hot it was in the summer compared to other towns in the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh). He devoted the third term of his prison sentence entirely to a study of socialism and communism. It was in the same jail that he saw acts of brutality that he did not think were possible in the so-called civilized world across the seas. He recounted how sick prisoners were, of course, given medicine, but otherwise left to sink or swim at the mercy of fate. “What a sick man lacked was nourishing food; the sick man’s milk was gulped down by the sick attendant” (Sanyal, Joys and Sorrows Behind Prison Bars). Among other things, fifteen seers (about 14 kilos) of corn were given to my father to grind every day on a heavy stone mill, sometimes for months together.

The prescribed amount of vegetables supposed to be served to each prisoner was “four chattaks” per prisoner, approximately 230 grams, daily (Joys and Sorrows). But prisoners seldom got this amount of vegetables, or any decent quality of nourishment, because they “got saag when the register may show potato,” and badly baked vegetables and roti were doled out instead (Joys and Sorrows).

At Agra Central – and earlier at Fatehgarh Jail – he also became closely associated with Govind Ballabh Pant, who later became Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, and subsequently the Union Home Minister. I remember that sometime in 1961, I accompanied my father and one of my uncles (D. N. Sanyal) to meet G.B. Pant in Delhi, who looked extremely ill at the time, trembling as he walked in with attendants and supported by a stick. This was a fallout from the time when, at Agra Central, he had come in between the batons of the jailers aimed at Nehru’s head. The blows had landed on Pant’s head instead, and had caused serious and permanent damage.

At one stage, my father was made ‘Convict Overseer,’ which he found to be a bad system. This system did, however, give him the opportunity to scrutinise underhand dealings inside the prison. Large amounts of food were pilfered by petty officers and sold outside. One particular jail superintendent, designated as a ‘Special Superintendent” since this was a jail for ‘B class prisoners,’ was reportedly rude to my father and very unfair. He used the tool typical of most English rulers then – divide and rule – with absolutely unequal treatment meted to different prisoners.

My father was released in 1945, around the end of WW2. He took to freelance journalism and was for some time editor of The Orient, then a political correspondent for the Amrit Bazar Patrika in Calcutta, and then moved back to U.P. as the government’s Principal Information Officer (when G.B. Pant was the Chief Minister there). He wrote Facets of Indian Politics and published it from 2 Canning Street, Allahabad, the residence of my uncle D.N. Sanyal.

My father was also associated with newspapers like Aaj (Benaras) and Northern India Patrika (Allahabad). He went on to write prolifically. Some of his better-known works are Marx ka Darshan (Marx’s Philosophy), Marxwadi Arthshastra (Marxian Economics, for which he was awarded the Murarka Prize by the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan), Francisi Sahitya ka Itihaas (A History of French Literature), Joys and Sorrows Behind Prison Bars, Facets of Indian Politics, Adim Manav Samaaj (Ancient Human Society), and Manushya ki Utpatti (The Evolution of Man) – these last two were books on anthropology. He also wrote a series of children’s books like Hamaari Desh ki Nadiyan (Rivers of India) and Ganit ki Kahani (The Story of Mathematics). These were in addition to innumerable articles in all the leading publications of the time, including some abroad.

In 1950, the family moved to Allahabad from Lucknow. We stayed at what is now a historic address, 9 Albert Road, as tenants. The landlords were Mr. and Mrs. Keki Ghandy, Feroze Gandhi’s sister. It was here that my father became a senior empanelled member of the Central Hindi Directorate. This house is also memorable because it played host to a number of stalwarts of the freedom movement, all of whom visited my father frequently – people like Kailash Nath Katju, Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, Prem Kishan Khanna, Jogesh Chandra Chatterjee, Kamal Nath Tewari, Ram Kishan Khatri, and a host of others, amongst whom was a very affectionate man called Lal Bahadur Shastri.

Postcard written to my father six months before Shastri became the Prime Minister

We moved from Allahabad to Jaipur in 1959, with the immediate family comprising my mother Bina, my sister Champa (now Champa Sinha) and me. Both cities belonged to an era now past, and my sister and I went to school in Jaipur, she at Maharani Gayatri Devi and I at St. Xavier’s. My father was then in All India Radio, Jaipur, from where he joined his friend’s weekly paper, Thought, published from Daryaganj in Delhi. After my sister’s college years and my initial stint in Maharaja’s College, we resettled in Allahabad at P 42 Church Lane, very close to Anand Bhavan, Motilal Nehru’s paternal residence. Also close by was my eldest cousin, Sachindra Nath Sanyal’s son Ranajit, who later became a Chairman of the UP State Electricity Board. We moved to Benaras in 1970 – staying at B 25 Sonarpur, Varanasi.

My father’s struggle after Independence was, ironically, greater than during his days in jail. He could never quite manage to settle down after the closure of the Amrit Bazar Patrika. His time at All India Radio, when we were at E 61 Chittaranjan Marg, ‘C’ Scheme, Jaipur, was a far cry from engaging the mammoth intellectual and incisive mental faculties that he undoubtedly possessed. Long years of irregularity and uncertainty finally started telling on my father’s health, which broke down gradually in the last years of his life. His once-strong physique thinned a little prematurely, but his indomitable courage reflected itself in his silence about the serious ailment he must have been nursing for quite some time. His last days were monitored from 1-F Church Lane, Ranajit Sanyal’s house in Allahabad, and from Edmonston Road, where my cousin Jayant used to live.

On 3rd January, 1972, my father died in Allahabad, in Swaroop Rani Hospital, at about 3 in the afternoon. We cremated him at Daraganj Burning Ghat deep in the night. I shan’t forget the night, the crowds, the press, his innumerable friends, and our close relations.

I attach some of the homages that came in after my father died. They might reflect some of the flavours of the movement which brought the sun to set on the Empire that had occupied the Indian subcontinent for two hundred years. The images may also express a sense of some of our childhood.

A letter from Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, sister of Jawaharlal Nehru, on my father’s demise.

Homage to my father from Jaya Prakash Narayan, Indian Nation newspaper. Patna. January 1972.

Northern India Patrika, 6th January 1972

Letter of condolence from Chandra Bhanu Gupta, long-serving Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh.

The text of Chief Minister C B Gupta’s letter reads:

"Dear Surajit, I received your letter dated 6th January, 1972. I was deeply grieved to hear of the sudden death of your father, Mr. Bhupendra Nath Sanyal. Your late father was not only a close associate and colleague, but also an extremely dedicated revolutionary comrade of mine. He was a leading player in the Kakori Conspiracy. I am deeply hurt and shocked by his sudden death. In the fight for freedom, his contribution was exemplary and unparalleled. I pray his soul rests in peace and you have the strength to bear this huge grief. Please accept my heartfelt condolences in your hour of grief."

His close association with Subhas Chandra Bose led to many invitations to many memorials

Epilogue

“One half of the world must sweat and groan, that the other half may dream”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Hyperion: A Romance

I was born just before India was declared a Republic, on 1st January, 1950.

In independent India, however, when I look back on my early years in Allahabad, it seemed an oasis of peace – 9 Albert Road, Civil Lines, Allahabad, a city that was a cultural, political, and literary cauldron then – no sign of strife, a picture of harmony. Our landlady was Feroze Gandhi’s sister, who also owned one of the better cinema halls in town, the Palace. Mr. Keki Gandhi and Mrs. Gandhi were lovely, old-world Parsis. This conjures up images of the only outdoor ice-cream parlour then in UP – Guzdar’s, as elegant as they come. Another Parsi association that comes to mind was the Finaro Hotel in the High Court area. Of course, the great university was there, with its many colleges and hostels. You’ll find enough of Allahabad’s early and later developments, its contributions to academic and intellectual life, in literature past and present.

Feroze Gandhi used to drop in ever so often and chat with my father on a charpoy (a wooden-legged bed with wire ropes forming the bedrock, skilfully woven, crisscrossing the base) on a patch of semi grassland hemmed in by mehndi hedges. I never realised the importance of being earnest in following my father’s vast acquaintances, colleagues, fellow freedom fighters, and close friends on the same venue through the years. Our neighbours were a cosmopolitan lot, ranging from Anglo-Indians, UPites, Punjabis, Parsis, Bengalis, Sikhs, all in the same compound, with what was known then as the ‘outhouse’ housing a fair number of Muslims (mainly bakers and tailors) and Hindus together. This was the picture in Heartland India.

The author (left), with his sister and parents in Allahabad (1956-57).

My father and uncles were a satisfied lot with this tranquil social integration and must have been satisfied with the outcome of whatever they contributed to; their political views notwithstanding, India was freed from the foreign yoke at least. Building and rebuilding the nation was in the hands of the political class – my family was out of it.

As a family, however, we paid a price. Financially, and consequently socially. In 1947, my father was 41 years old and completely rootless. Rebuilding finances at this age and getting reasonably paid employment was an uphill task. He took to journalism eventually, and had a vast repertoire of employers – mostly his friends, like Frank Moraes of the Express; Ram Singh, a former colleague in the revolution, who edited a magazine called Thought from Daryaganj in Delhi; Rajni Kothari, of the Economic and Political Weekly; and the owners of Dinaman, a Hindi monthly published along the lines of Time.

My father wrote on a vast range of subjects, mostly in Hindi, and was the lead translator for the Central Hindi Directorate in Delhi. His stint in Allahabad with a newspaper called Amrit Patrika (the Hindi edition of the famous Amrita Bazaar Patrika of Calcutta) came to an unceremonious end, with the owner deciding to close shop in 1959.

Jobless again.

This signalled our migration to Jaipur. Though we weren’t quite in the pink of health financially as a family, we were accorded panaah, security, in the Pink City. That was the end of the year, 1959. Felt strange.

From Allahabad’s typically coffeehouse culture and a literary vibrant society, to the boomtown of Jaipur. Construction looming everywhere. Definitely feudal at one divide and very commercial at the other. Immensely hospitable people. For us, a migration with no roots, with the rootlessness coming from an early sacrifice for a greater cause. I saw in the eyes of my mother what she had to leave behind – associations, emotions, and social security.

My father never mentioned his or his brothers’ sacrifices and the indubitably massive toll they took on the family’s emotional and physical health.

After a couple of months of disorientation, though, the place fell into a familiar pattern. Jaipur came to be a city we loved. For me and my sister Champa, 72 years old now, it was the best of times.

St. Xavier’s School for me and Maharani Gayatri Devi Girls Public School for my sister were gifts from my parents, who sacrificed their own comforts and conveniences to enable us to acquire a lifetime of security and happiness. Today, our best friends, selfless in their love, are from Jaipur. Little did I realise that I would come to regard Jaipur as my second home today.

No, it is not strange that I do not regard Allahabad, or even Gorakhpur, where I frolicked about in abundance, as my homes – the music there isn’t gentle anymore, and my father and my uncles would not have been happy with the way in which the social fabric is being torn asunder today.

And, nationalists galore! Nobody instructed us in our careless, simple childhoods, that we had to symbolise this or that to enable us to be certified as nationalists. We just accepted that we were patriotic Indians to the core, in mind, heart and spirit. An interesting footnote: the Khadi Gramodyog Bhavan on Mirza Ismail Road, Jaipur, was a great beneficiary of my father’s presence. He only wore khadi, mostly kurta-pyajamas. He had few clothes and fewer needs – other than a pronounced weakness for doodh-ruti-gur (roti with milk and jaggery). So atmanirbharata was in his blood.

My mother was similar. She came from an ascetic family – her uncle, my granduncle, was Swami Jyotishwarananda, sometime President of the global Ramkrishna Mission organisation, and my mama, maternal uncle Swami Propponananda, heads the West US Ramkrishna Mission in Syracuse, California.

I have met so many of my father’s and uncles’ friends, some of whom were signatories to the Lahore Central Jail letter mentioned above and others who were my father’s Kakori case batchmates – not one of them carried their nationalism on their sleeves. Now, long distance patriotism from foreign lands trumpeted on social media amuses me.

My uncle Jatindra Nath Sanyal went on a fast with Jatin Das and Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and others, in the Lahore Central Jail.

Letter of protest to the government written by the inmates of Lahore Central Jail

My eldest uncle Sachindra Nath Sanyal’s trials and privations are folklore, he having served not one, but two life terms in the Andamans.

My other uncle, Rabindra Nath Sanyal, was interned in Gorakhpur in the Terai region of Uttar Pradesh. The British authorities hoped he would succumb to the elements in this place that my uncle, quoting the Government of India Gazetteer, described as a “filaria-ridden, malaria-ridden, dacoit-infested, Class IV hill station.”

Bhupendra Nath Sanyal, my father, was force-fed in Agra Central Jail during his solitary confinement there, through his nose – he was on a fast, demanding prisoner rights. This torture had long-term health implications, leading to his early death in 1972, when he was 66.

My father, a polyglot, liked to quote Alexandre Dumas – “All human wisdom is contained in these two words, ‘Wait and Hope.’” Let’s wait and hope that, someday, the India of their dreams comes to blossom.

_______________________________________

© Surajit Sanyal. Published February 2021.

Comments

Freedom.

A piece of history of a great

Tribute to the band of brothers

the article

The heart is filled with awe

Unbelievable

SUROJIT sanyal's article

Add new comment