Latest Contributions

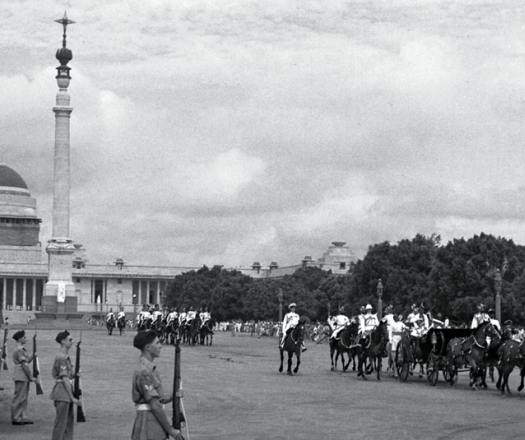

Independence Day 1947, Delhi

Category:

R C Mody is a postgraduate in Economics and a Certificated Associate of the Indian Institute of Bankers. He studied at Raj Rishi College (Alwar), Agra College (Agra), and Forman Christian College (Lahore). For over 35 years, he worked for the Reserve Bank of India, where he headed several all-India departments, and was also Principal of the Staff College. Now 82 years old, he is busy in social work, reading, writing, and travelling. He lives in New Delhi with his wife. His email address is rmody@airtelmail.in.

![]() India would be independent one day. This was the fond hope, in fact a dream, with which most Indians of my generation grew up. But this dream kept on eluding us.

India would be independent one day. This was the fond hope, in fact a dream, with which most Indians of my generation grew up. But this dream kept on eluding us.

Every time freedom appeared to be close in the 1930s and early 1940s, there would be a setback, with the British throwing back the leaders of the Independence movement back into jail. And then for long, nothing would be heard about it. The cynics would say, “The British will never leave India.”

When World War II ended in 1945, it seemed that the British had finally decided to leave. There was only one lone protestor in Britain, Winston Churchill, who was ignored by the new British Government formed at the end of the war.

But now some of our own people would not let them go. The Muslim League, which claimed to represent over 20% of us, insisted that the British should partition the country before they left. The League's claim was backed by violence on an unprecedented scale. The idea of breaking-up India initially horrified the vast majority of Indians. But, gradually, people accepted partition as the price of getting the British out.

The historic announcement that India would be free but partitioned came on June 3rd, 1947. The actual date of the transfer of power, the 15th of August, was announced a few days later.

I was a student at Lahore, awaiting my final University examination. To escape the communal strife that had gripped Lahore, I had gone to stay for some time with my uncle in a nearby canal colony. It was there that I heard the radio broadcast on June 3rd. Mohammed Ali, my uncle's orderly, was by my side. When he heard of the partition, he shrieked, and said woefully, "Sahib, mulk ka batwara nahin hona chahiye (Sir, the country should not be split)."

Within days, I went back to Lahore. I found out that our examinations had been postponed indefinitely. The college authorities asked all the students staying in the college hostels, like me, to leave and return after the 15th of August on a date that would be announced in due course. I decided to go back to Alwar, my hometown, some 400 miles away.

I locked my belongings in my hostel room nunber 14. I had no doubt that I would be back there within a few months!

Then, it did not matter to me whether Lahore would be in India or Pakistan. I was simply under the spell of the approaching freedom, even at the cost of the partition. In any case, I believed, as did many others I knew, that the communal unrest would soon fade away, and life would return to normal.

The weeks that followed were packed with swift developments, hopes and excitement. The vast framework of an Empire assiduously built over more than 200 years was to be dismantled within just two months. Every day, the newspapers and radio (there was no TV then) brought some exciting news: passage of Indian Independence Bill by the British Parliament, the time table for the departure of British troops from the Indian soil, the shape and colours of the flag to be adopted by the emerging nation, the names of the members of the national government that would assume power on the appointed day. (By now, these leaders have all passed into history, with Jagjivan Ram and C.H. Bhabha, the youngest of the lot, being the last to depart).

As Independence Day came nearer, I made plans with my family to be in Delhi to experience first hand the thrill for which we had been waiting so many years.

Travel from Alwar to Delhi had been disrupted by the riots that had broken out. Nevertheless, we managed to reach Delhi by train late in the evening of 14th August. The city looked fully dressed for possibly the greatest event in its 900 years of recorded history. The illuminations at the Delhi railway station and around dazzled us. A giant wheel illuminated by blue lights, replicating the Ashoka chakra in the middle of the India's new flag, was revolving on the top of the railway station building. Though there was some tension in the air, it appeared that people had for the time being set aside their fears and apprehensions in order to celebrate with full gusto an occasion that comes only once in the life of a nation.

By the time we reached Delhi railway station, it was too late for us to move into the city. We decided to spend the night at the railway station, and were lucky enough to get a place in the retiring rooms. (A few months later we learnt that Mahatma Gandhi's assassins spent a night in the same retiring room when they reached Delhi to kill him in January 1948).

We had no access to a radio set that night, and missed listening to Jawaharlal Nehru's famous ‘Tryst with Destiny' speech and to the proceedings in the Constituent Assembly, heralding the advent of freedom at midnight.

The first thing we did after waking up next morning was to confirm that India had really become free last night! This was easy. The railway platform was strewn with morning editions of all the daily newspapers, which had banner headlines conveying the great tidings. On all front pages appeared a message of greetings from the British Prime Minister Clement Attlee to his Indian counterpart, Nehru, wishing India, "a future greater than her past".

Now we had to decide where to go to witness the great occasion. No one could tell us what the day's programmes were going to be. We took a snap decision, which turned out to be the right one, to rush to Great Place (now Vijay Chowk) at the foot of the Raisina Hill. It was a long distance to cover by tonga, the only vehicle those days. En routé, we saw the city draped in tri-colour in various ways, including the colours of the saris worn by some women.

When we reached the Great Place, we saw, to our dismay, the British Union Jack still flying over North and South Blocks of the Secretariat and the Council Chamber (now Parliament House). There was a murmur of protest in the crowd. We heard someone say that India would have to wait for some months before the Indian flag replaced the Union Jack there. But, within minutes, amidst thunderous applause, some dhoti-clad men climbed up the minarets, pulled down the British flag, and replaced it by the national flag.

The dream had at last come true. Many eyes were moist. For my late father, it had yet another significance. Thirty-six years earlier, as an 11-year-old boy, he had seen King George V and Queen Mary crowned as India's sovereigns in this very city. For him, history had taken a full turn.

A short while later, at around 10.00 am, a motorcade emerged from the Viceroy's House (re-named Government House that morning, and subsequently Rashtrapati Bhavan in 1950). It came down Raisina Hill, carrying the leaders of the new government, who had been sworn in a few minutes earlier, and other dignitaries to the Council Chamber, where the sovereign Parliament of independent India was to hold its inaugural session. The first limousine carried Jawaharlal Nehru, who waved and responded to the crowds with his characteristic zest. Then, one after another, we saw cars carrying Vallabhbhai Patel, Rajendra Prasad, Maulana Azad and others.

Soon after the motorcade had passed, we witnessed the smart troopers of the Governor General's bodyguard (a 175 years old unit in existence since the time of Warren Hastings), on horsebacks, coming down the hill. Then came the ceremonial coach carrying Lord and Lady Mountbatten.

This carriage descended the Raisina Hill and took a turn to the left towards the Council Chamber, the point where I was standing. The crowds spontaneously shouted "Pandit Mountbatten ki jai" thus showing their awareness of his changed status from that of a representative of the British monarch to that of the head of the new Indian state, chosen for that position by representatives of the people of India.

Some people went up to the carriage and shook hands with Lord and Lady Mountbatten! This was clear evidence of the change that had taken place over night. The day before, no common man could dare go near the Viceroy in this manner. The spectacular procession ended, a short distance away, at the Council Chamber where Mountbatten, as head of the new state, was to inaugurate the session of the Parliament. With this ended the ceremonies of the forenoon, and the crowd gradually dispersed.

In the evening, there was a function at the Princes Park (as the area around India Gate was then known). The event was billed as a "Flag Salutation" ceremony but I could never find out how it was expected to go. All that I now recollect is that there were scenes of uncontrollable enthusiasm and cheerful confusion all around. At some point, Mountbattens arrived in the same ceremonial carriage.

And, then suddenly, 58 year young Jawaharlal Nehru emerged from nowhere. He ascended the pedestal at the back of the ceremonial carriage and from there made it run unceremoniously through the jostling crowds on the India Gate lawns, with Mountbattens waving to the crowds, helplessly and cheerfully. There were no security guards around. To me, the event symbolized collapse of the Empire and emergence of democratic India.

The evening ended amidst a pleasant confusion, laughing and jumping of the crowds. Just before the crowds dispersed, there was a mild drizzle followed by sudden appearance of a rainbow in the sky. It was taken by all as a good omen\; heavens, they felt, were blessing India on its independence.

The day thus came to an end. While retiring that night, awfully tired, I was fully aware that I had witnessed a great day that would be remembered by Indians for centuries to come. And yet I could not foresee that some half a century later, the event of this day would be chronicled the world over as one of the greatest of the millennium and one of the greatest in the history of Democracy.

Next morning, 16th August, the newspapers reported that Nehru would to address the nation from the ramparts of the Red Fort in the morning. (I wish to tell the readers firmly that it is a travesty of history to believe that the first hoisting of the national flag at the Red Fort took place on 15th August 1947. In 1947, it took place on 16th August. Since the year 1948, it has been taking place on 15th August.)

Since we were staying close to the Red Fort, we rushed to listen to Nehru's first public speech as India's Prime Minister. The crowds were not unmanageable, as many people had not found out about the event in time. Nehru appeared in a fawn coloured Jawahar jacket, not the formal white sherwani of the preceding day, indicating an air of informality. He unfurled the national flag, greeted the crowd with Jai Hind and spoke for about half an hour in a solemn measured tone.

I recollect two specific points of his address. He referred to Netaji Subhas Bose's dream to see the national flag unfurled at Red Fort. In a sad but firm voice, Nehru regretted that while the dream had come true, Netaji was not alive to see it. Perhaps it was Nehru's attempt to set at rest the doubt in the public mind during preceding two years whether Netaji was dead or alive. (The doubt persisted for decades even after Nehru's speech.)

In another observation, Nehru referred to India as a nation of 33 crores. I remember it sending a shiver down my spine\; we were 45 crores till just two days ago.

For me, the Independence Day celebrations ended with this function at the Red Fort.

I met a number of my Lahore friends in the crowds on these two days. They told me their stories about how they managed to reach India in the turmoil. All were eagerly waiting to know on which side of the border their city would fall. The Radcliffe Award drawing the boundary line between India and Pakistan came a day or two later when I was still in Delhi.

Lahore went to Pakistan. I still thought that I would get back there after a month or two.

I did go back, but after 52 years (in 1999)! And that too only for a week. I did go also up to room number 14 in my hostel. Of course, it did not bear my lock any more. But its occupant, my grandson's age, received me with warmth. He presented me a bundle of Urdu books, which, I felt, compensated me fully for the belongings that I had left behind over five decades ago

© R C Mody 2009

Comments

Add new comment