Latest Contributions

Shaheed Bhagat Singh: His Martyr’s Notebook

Category:

Tags:

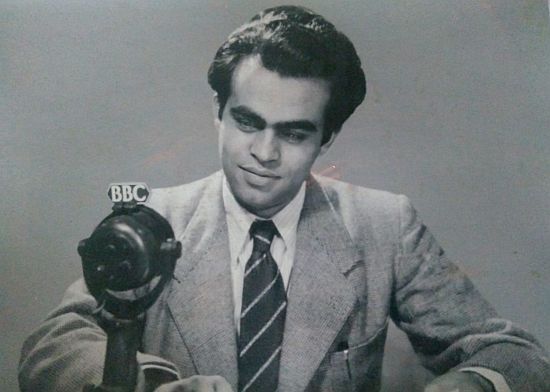

Bhupendra Hooja, born in Lahore in 1920, was a revolution focused student leader, an aspiring actor, a moderately successful scriptwriter and author. In the 1940s, he was a broadcaster for All India Radio and BBC in London. In the 1950s, he was civil servant in Delhi and later an Indian Administrative Service officer in Rajasthan. After his retirement in 1978, be became the editor of the Indian Book Chronicle. He passed away in 2006.

Bhupendra Hooja. London. Late 1940s.

Rakshat Hooja writes:

Inqilab Zindabad! Let the revolution live forever. Bhagat Singh made this phrase popular in the 1920. He was a revolutionary and a martyr, who was one of the central figures in India's freedom struggle.

The British hung Bhagat Singh and his comrades Sukhdev and Rajguru on the evening of 23 March 1931 in Lahore.

In 2018, Bhagat Singh's memory and ideas live on in India and Pakistan. He lives on as the cult or legend of Bhagat Singh -the historical person. He is also the inspirational essence and definition of a revolutionary who is willing to give up his life for his cause. Perhaps the revolution never happened. Perhaps its ideals don't live on. But the slogan Bhagat Singh Zindabad (Bhagat Singh will live forever) that rang out across parts of north India the news of Singh's hanging spread certainly rings true today.

In the last three decades, there has been increased academic and public interest in Bhagat Singh. A small part of this interest is due to the publication of Bhagat Singh's "Jail Notebook" or the collection of notes kept by Bhagat Singh when he was in prison between 1929 till his death.

For many people, this Notebook is Bhagat Singh's most famous text, even surpassing the popularity of his essay Why I am an atheist.

The story of the "publicification" of Bhagat Singh's Jail Notebook starts in 1991. That was the year in which Bhupendra Hooja started serializing the Jail Notebook of Bhagat Singh in the Indian Book Chronicle, a monthly English Journal that he edited. In 1994, he published an extensively annotated version of the Jail Notebook as a book: A Martyr's Notebook. This was the first time that the world was exposed to an approximately 22-23 year old Bhagat Singh's thoughts and readings.

Bhupendra Hooja, my grandfather, had a left leaning ideology, and a belief that the youth have the power (and obligation) to revolutionise and change society. Perhaps that and the fact that Bhagat Singh most likely was a childhood hero are the reasons he devoted four years of his time and money into annotating and finalising publishing Bhagat Singh's jail notes.

The making of A Martyr's Notebook was a unique experience in our family. I lived in a joint family that focused heavily on writing. Many family members were published authors. The monthly journal, Indian Book Chronicle, was edited on a shoestring budget from a small one-person office in our home. Even at the young age of 10, the idea of writing, editing and publishing was familiar to me. I was not yet at an age where I could partake in it, but it was something I considered routine. But the publication of Bhagat Singh's notebook was different. It was a passion project for my grandfather that had to be completed and a certain standard maintained no matter how much time, money and effort it took.

I remember my grandfather's excitement when he first got hold of a copy of Bhagat Singh's jail notebook. He would not stop talking about it. He got it from his older brother GBK Hooja, who had also been in the Indian Administrative Service, and later was the Vice Chancellor of the Gurukul Kangri University. On a subsequent inspection visit of Gurukul Indraprastha, near Delhi, he came across a hand copied/duplicated ‘diary' of Bhagat Singh. Realising the significance of the ‘diary' and hoping to one day get it published as a book, GBK had latched onto the text.

The job of bringing the ‘diary', which actually was a notebook, to the public fell upon the shoulders of my grandfather.

He could have written a short introduction and published the notebook verbatim. But, seemingly due to genes that loved to complicate projects and make them never-ending, and other reasons best known to him, he decided against this. Instead, he decided that the notebook should be presented to the public in a format where every notation had been annotated, the source material explained and contextualised, and editorial context provided to the notes and sections along with some conjectures.

He believed that these editorial additions would make the notebook more meaningful and accessible to the potential readers. Maybe even influence and inspire them!

Now, it was important to verify the notebook's authenticity. GBK Hooja was sure it was authentic. It was the discovery of another set of notes, this time typed, that put Bhupendra Hooja's nagging doubts to rest, and gave him the confidence to move ahead.

One conversation of my grandfather's that I remember is with I K Gujral, his friend from young days and a future Prime Minister of India. He wanted the Indian Book Chronicle to publish something about the Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946, as he felt its importance was being forgotten. The Indian Book Chronicle did publish a special edition on the Mutiny later. This dialogue is etched in my mind because I met Gujral Sahib in Delhi in 2000. At that time, he wanted me to expand the Indian Book Chronicle article into a full book on the Mutiny. I ignored his suggestion and regret it till date.

The efforts of the Hindustani Manch, a small forum of Jaipur citizens, helped greatly in the publication of this book. The Manch's objective was fostering communal peace and harmony, restoring mutual amity and trust between the estranged communities, and spreading the notions of Hindustaniyat (Indian-ness) and Insaniyat (Humanity). The Manch was born on 23 March, the same day as Bhagat Singh's martyrdom, in 1989. Sardar S S Oberoi, Dr R C Bharatiya, Professor R P Bhatnagar, and Sardar Satwant Singh are some of the members of the Manch (along with the Hooja brothers) whose names I remember.

One question still remains. Why did Bhagat Singh write these notes? What was his actual purpose? What was he trying to achieve? We can all conjecture but I don't think anyone can provide a definitive answer.

For sure, Bhagat Singh's jail notebook now belongs to the readers. Why not go through A Martyr's Notebook and find your own answers, conclusions, questions?

The complete book is attached as a pdf file. I have selected some pages to display here.

© Rakshat Hooja 2018

Comments

Add new comment