Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Memories of 1940s Campbellpore

Category:

Tags:

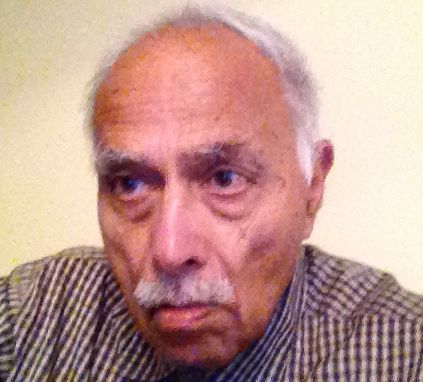

Dr. Anand - an unholy person born in 1932 in the holy town of Nankana Sahib, central Punjab. A lawyer father, a doctor mother. Peripatetic childhood - almost gypsy style. Many schools. Many friends, ranging from a cobbler's son (poorly shod as the proverb goes) to a judge's son. MB From Glancy (now Government) Medical College Amritsar, 1958. Comet 4 to Heathrow, 1960.

Long retired. Widower. A son and a daughter, their spouses, five grandchildren, two hens (impartially, one black, one white) keeping an eye on me as I stand still and the world goes by.

In Campbellpore, now vanished from the maps! (Ed. Renamed as Attock by Pakistan).

In 1942, my mother, tired of seeing my father's difficult journey from Lahore, where he worked as a lawyer, to Muktsar, where she was posted as a doctor, requested the Government to transfer her to a nearer 'station' (the term then used in government service for postings).

However, the Inspector General of Hospitals, Punjab, decided to send her to Campbellpore - more than 400 kilometres from Lahore. The rationale was that instead of two or three changes of train from Lahore to Muktsar, my father could travel straight from Lahore to Campbellpore by Frontier Mail. A ten-hour journey. Then, a tonga ride to our hospital house.

It was Sir Colin Campbell, later elevated to a peerage, whose name was given to the township that sprang up next to a cantonment where the British troops were quartered. In my time there, the district headquarters were located at Campbellpore. It was described as "District Attock at Campbellpore".

[As it was Sir Colin Campbell who defeated my ancestors at Gujrat in the Second Sikh War in the 1840s, I do not have a soft spot in my heart for him].

As was right and proper for a District Headquarters, the city had a very well-equipped hospital. The government-provided homes of the two doctors, one male, one female, were large with decent courtyards, and had "gardens" where we could and did grow vegetables. Our home already had beautiful lilies, narcissi with heavenly perfume, sweet peas, and nasturtiums. All these flowers were new to me.

Nearby, at the office of the Civil Surgeon (he was the district head of the hospital services), there were more and prettier flowers than any I had ever seen before. And there I ate, for the first time, cape gooseberries (botanical name then was Physalis edulis, Rus bhree in the vernacular), which are altogether different from the gooseberry. The hospital Malee (gardener) was not pleased that I had eaten the ‘Silber Sujjan' (Ed. civil surgeon) Sahib's special delight. I promised to be good.

It was a very dry area. I found myself standing one day, on a sandy, gravelly spot, with may be a score of small and a few large scorpions whizzing around my chappal-clad feet. However, they were very friendly, and they did not seem to mind that in my swift get away I squashed some of the family.

Outside the perimeter of the bungalow, next to the bathroom, there was a large "pit", lined with impermeable concrete - cement. The sweeper, known in the vernacular as Bhangi (reputedly all male sweepers imbibed Cannabis = Bhang), or Mehtar, would empty out the tank. The sweepress was called Mehtrani.

A vagary of language: the sweeper was also known as Jamadar. Unfortunately, the Viceroy's Commissioned Officer was also designated Jamadar\; the next rank up was Subedar, then Subedar Major. The last-named rank merited the highest regard of the colonel, who would address the S-M as Subedar Sahib. All others would call him "Major Sahib".

I do not know what the present etiquette dictates.

Once I chanced upon a wild plant, thick leaved, oozing a white milk if a twig was broken. Poisonous plant, locally known as Uck. Later, studying botany, I learnt that it belonged to Calotropis species. But my interest then was in the beautiful caterpillars feeding on its leaves. I would put the caterpillars in an empty shoebox, feed them on Uck leaves, watch them pupate and then escape as fully-grown butterflies - out of my room. It took about two weeks to complete the process.

The walled courtyard was big enough for the family to sleep there, in the hot summer, under the stars, on charpoys\; the name is self-explanatory - the bed had four (char) legs (poys). (A tipoy was a three-legged table).

The charpoy was light enough to be carried in to the Verandah (Baraamdah) if it rained. Like many other acquisitions from the Indian languages, verandah is now a respectable English word.

We would roll up the bedclothes, if there were a strong air current swirling rain in to the Verandah.

Our residence was, perhaps, a hundred yards from the "small pox ward". There were occasional cases of patients with suspected small pox. One telltale sign was my mother calling out to tell us to stay away from her while she disappeared in to the bathroom and divested herself of the possibly infected clothes. Looking back, I am not surprised that one took it so calmly\; it was "normal Indian life". We, the children in the family, were vaccinated every year.

[Nearly fifty years ago, in England, after visiting a suspected small pox case, I too would call out to my wife and children to get out of the way while I de-robed, put the possibly infected clothes in to a special laundry bag, shower and then join the family.]

It was wartime. As the German troops advanced in to Russia, we started to see people who described themselves as Russian, looking for food. It is hard to believe that the German forces had pushed so close to British India. However, in 1943, the civil defence staff labourers started digging trenches not far from our house. There were just three or four, and I imagine these were meant for anti-aircraft guns, just in case. There were only practice air raid sirens. The trenches were good for playing in.

In 1943, there was the Great Bengal Famine. It was of truly huge. Two to three million Bengalis died. Many more travelled all over India. Some even reached Cambellpore. I remember a poor shrivelled young lady with an equally shrivelled baby, begging me, and anyone else nearby, to take the baby, and that she would do anything in return.

What caused the famine in Bengal? At that time, we knew not. Fate. Karma. In Punjabi, Rub dee Murzee (God's Will). Now we know that Bengalis did not like to eat wheat, and that Churchill preferred to ask for American ships for the War Effort, but not for importing rice.

Although Punjab had had no harvest failure, many things there were in short supply, and there was rationing of food, atta (flour), and sugar. At every entrance to a town or city, there was an "Octroi post"\; translated in to Urdu, the legend read Mehsool ki Chungi. Import of food grains (wheat, maize = corn to the Americans, rice), sugar into the city was banned - heavy fines for smuggling, even for domestic use. Of course, the system meant some extra, "black" income for the regulatory staff, who scared the living day lights out of any who broke the regulations.

My maternal grandfather, a farmer in Central Punjab, was not permitted to send us wheat.

Paper was in short supply. This made the writing of essays etc. difficult. Maths did not suffer too much - the custom was to use "slates" at school. These slates were seldom made of slate, the metamorphic rock. They were metallic, coated with a paint on which you could write with a "slate pencil", rub off and write again.

When writing Urdu, Devanagari, Gurmukhi, or Farsi, we could use the Takhti, a wooden writing slate also known as Phuttee. Children simply had to use the Takhti for practising good handwriting (Khush Khuttee).

A takhti was a flat rectangular piece of wood with a handle at one of the short sides. You painted it with a clay called Gaachi in the vernacular. This Gaachi was sold by stationers. You could also collect it from the banks of certain storm rivulets. [And in the North East Punjab, on the road leading from Pathankot to Dalhousie, in one area, there was a Gaachi da Pahar: a Gaachi mountain. The monsoon rains would wash large boulders of the clay down to the road, and then hurl down the steep gorge (Khud in Punjabi). Often there were accidents involving vehicles plunging down the eroded verge of the road.]

The takhti was a prized possession for us, the school pupils. And not only for calligraphy, which in Urdu and in Farsi, one tried to emulate the writings of the poets of a couple of centuries earlier. Farsi was a worthy hangover from the days of the Mughals. Maharaja Ranjit Singh (Sher-e-Punjab, Lion of Punjab) kept Farsi as a court language, besides introducing Punjabi in Gurmukhi script. Urdu was merely the language of the lashkars, a military camp language to start with. Later, it received the blessings of the kings and many noted poets and writers, Muslim, and Hindu turned it in to a language of high culture. The British turned Urdu in to a court language, English being the other court language in the whole of the Punjab.

The takhti was also a useful weapon of defence, and sometimes used for pre-emptive strike\; rarely for naked aggression.

We used a black ink for writing on the takhti, and with a "Zed" nib, for writing in Urdu, on paper. The War curtailed the supply of decent paper (which, I recall, was made by Shree Gopal Paper Mills somewhere in the East). Ink too was in short supply. We learnt to mix various ingredients to produce a primitive ink.

Talking of shortages, factory made soap was scarce. Our parents made soap out of sodium hydroxide and sarson da tel (oil of rape seed, botanically, Brassica campestris.) It was fine for washing clothes, though the skin would become very dry and peel off.

For cleaning the teeth, ordinary folk would, as usual, pluck twigs of Neem (Azadirachta indica) or Kikar (Acacia species) to chew, fashion into a brush, clean the teeth and return the twig to Mother Nature - hurling it into the vegetation by the side of the road or mud path as they went for the morning constitutional, uttering Ram Ram (Hindus) or Wahe Guru (Sikhs), or whatever the religion decreed.

It was a little harder for the Anglicised people, who had adopted the toothbrush and toothpaste. No problem getting hold of Made-in-India tooth brushes, except that the bristles came adrift in your mouth. Looking back, I wonder though which animal species supplied (unwillingly, no doubt) the bristles. Toothpaste was not available. So, a substitute was made at home - ground up charcoal mixed with ground salt. In our home, the charcoal came from the kitchen fire in the Chulha on we cooked our food. Our salt certainly came from the Great Salt Range, Khewra mines, situated in District Jhelum, located in the Pothohar plateau.

My headmaster had two sons. One was my classmate. The other, older, was a cadet at the Air Force Flying School at RAF Chaklala. When he was about to pass out of the School, one day he flew low over the School. Next moment, there was a bang. The plane had vanished. In a few minutes, we learned that he had crashed in the woods nearby.

P N Ghai was another of my classmates. Years later, in 1959, I was a house surgeon in a hospital in New Delhi. He was one of the registrars. I wonder where he is now.

The school children were mostly Moslems, reflecting the population composition. There was, in those days, no religious conflict.

In particular, I remember four Moslem boys who were very close friends and always went everywhere together. Once they invited me to their "village". If I remember correctly, it was called Syedan da Mohalla (the Syeds' Quarter). We were not "mates", in modern terminology, but they were exceptionally well‑behaved, very kind young lads. They were three or four years older than the rest of my classmates.

We had scouts in our school. In those days, there were three varieties of scouts:

- Bharat Scouts - Hindus in Hindu schools

- Muslim Scouts - Muslims in Islamia schools

- Boy Scouts - all comers, in government schools.

I was a Boy Scout, who reached the Tender Foot rank, half-way to the point of becoming a Second Class Scout.

As Boy Scouts, we wore:

- If Sikh, normal Sikh Style turban

- If Hindu or Muslim, a Muslim style turban-cloth (wound round a Kulla.)

In the Western parts of the Punjab, the Hindus tended to wear, either a round, brown cap, or a Muslim style turban - sensible to "blend" in to the background, rather than stick out as a sore thumb.

In ordinary school life, we - all boys - were bare-headed. The exception, of course, were the Sikhs, who wore their normal turban, wound round the head fresh every day, instead of taking it off on going home and slipping it back in the morning like a cap.

Most of the pupils wore the West Punjabi Salwar Kameez. Some of us wore the Central Punjabi Pajama Kurta - which instantly marked us out as "others".

Funnily, we never thought of the Welsh, the Scots, the Irish, or the English as Brits - they were all English to us. This, in spite of reading history and geography, and learning about the kings and queens, from the time of Henry VII to George VI.

Our studies of history and geography were of a higher order than those taught to English school children. So I found, well over half a century ago, in England. However, we knew next to nothing about the Football Clubs of the British Isles. And that is where the English school boys left me open mouthed with wonder. I still cannot understand this passion. Now, hockey would be a different matter altogether. Would it not?

One day, our Scout master, a Sikh (his religion or his turban, perhaps, was pertinent in this episode), took us for "tracking". Away we went, happily, a couple of miles out of the town, in to the wilderness, to a stream with some muddy water. Not a soul in sight, save us scouts in mufti (a word perhaps now expunged from the lexicons of Indian and Pakistani languages? A hangover from Pax Britannica - and that would never, never do in Resurgent India or Resurgent Pakistan. It is not Bombay English, nor Karachi English.). We were thirsty. The Scout master taught us to scrape a hole in the sand and grit about a foot, (about 30 cm to you who are metricated) from the water's edge, and well below the water level. We watched the water ooze in. It was clear, looking clean, (even if it was not). We cupped our hands and brought the water to our parched lips.

As we were busy quenching our thirst, along came a group of about a dozen teen-agers. Seeing them, some of our group disappeared. Clearly, they knew the area, recognised the bullies and melted away.

The Sikh Scout master, with perhaps a dozen youngsters, would have been no match for the teen-agers, who were also armed with hockey sticks. The young "gentlemen" used some choice Punjabi phraseology towards the teacher who replied in a very civil language. After a few minutes, our visitors told us to go, and away we went. Much relieved.

Did the Scouts who quietly slipped away ever disclose to the Headmaster or to the Scout master, who the bullies were? I do not know but I do not think so. They just returned to the next training session as if nothing untoward had ever happened.

One of the teachers had a very well-deserved reputation for the sadistic punishments that he inflicted on his fifth class (ten year old) pupils. No one seemed to take him to task. One day he overreached himself and beat a boy so much that even he could see that the child was unconscious. Then, this sadist arranged for a charpoy to carry the boy to the hospital. We saw him following the patient to the hospital, crying to the heavens above to save the child. The boy must have recovered. The teacher disappeared. We heard no more. Which was odd.

In 1943, we had a normal winter. We school children used to knock holes in the bottom of tins and hook a wire through the upper part to make a handle. Then we would load up the tin with pieces of wood or even charcoal, put a glowing ember at the bottom, and swing the contraption through the air very fast so that nothing dropped out. The fire would light up. This was our mobile "heater". We were permitted to keep it in our classroom. There was no heating of any kind in schools then\; perhaps there is none even now.

One day, the normal winter rain. Then, I saw something totally out of my ken. From the clouds above fell cotton wool. It was - snow flakes. For the first time in fifty years, said the locals, it snowed in the plains of Campbellpore. I had never seen snow in my life, though I had seen ice on the mountain through which Banihal Pass connected Jammu and Kashmir.

In 1943 or 1944, there were two occasions when a live cloud blanketed off the sun for a couple of hours. Swarms of locusts which, we heard, had bred in Africa, flown across the Arabian Sea, gobbled up crops and tree leaves in Western India but left Central Punjab untouched. We heard that the food-less villagers had been driven to eating roast and fried locusts.

We saw a few locusts which dropped off as their fellow travelers wended west. We could not bring ourselves to roast or curry them. They looked like, as they were, grasshoppers. The birds certainly had a feast.

1945 summer, came the orders for my mother to move again. This had been the longest stretch of schooling I had ever had and I had made friends. The time for farewells. But then the Gypsy Life must take over.

______________________________________

© Joginder Anand 2015

Comments

My grandma

Add new comment