Latest Contributions

My Early Years - 1

Category:

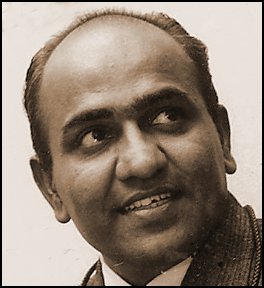

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

Editor's note: This story is reproduced, with permission, from Mr. Nagarajan's second not-for-sale book of his memories, Self-Portrait: The Story of My life, 2012. This website has several excerpts from his first not-for-sale book A Pearl of Water on a Lotus Leaf &\; Other Memories, 2010.This story is the first of three sequential stories about his early years.

Preface

I was born before penicillin, television, Xerox and contact lenses. There were no credit cards, laser beams or ball-point pens. We had never heard of FM radios, tape decks and electric typewriters.

We had never heard of FM radios, tape decks and electric typewriters. The telegram (then called ‘wire') was the fastest mode of communication\; and everyone assumed that invariably a ‘wire' brought only unpleasant news. If you saw anything with ‘Made in Japan‘ on it, it was junk. ‘Aids' were helpers in government offices. Perhaps, we were the last generation to believe that a woman needed a husband to have a baby. No wonder today my grandchildren call me ‘old fashioned' and consign me to a generation which would soon be extinct.

The entire fabric of the society into which I was born and grew up and the style of life I witnessed have changed. Today, my grandson, a software professional, can't believe that I went to a school housed in a shed meant for a temple chariot. There was no electricity to light up our home, and I walked to my college without footwear. My grandmother, a widow, would get her head tonsured regularly every month\; and I grew up in a house as part of a large family consisting of eleven brothers and four sisters, all born to the same parents.

The premise that nothing valuable can be taken from the ancient, or nothing ancient is as valuable as what we have now is not an acceptable position. An understanding of the roots they belong and the importance of heritage and history is necessary to the present generation. I have written this account of my life with this objective in mind. One day, perhaps, my grandchildren or their children or someone from their generation, may find this journal a kaleidoscope through which one could view the splendorous roots of the tree of which the viewer is a part.

Early Years

When I think of my school days, the first thought that comes to my mind relate to the enjoyable time I spent talking to my mother after her catnap in the afternoon. I loved telling her about my friends and the day's happenings at school, all in great detail. On some days, my reports merely elicited a grunt or a smile\; on other days, she was prompted to tell me a story. I loved her stories. She seemed to like my curiosity and found an interested listener in me. No one else in the family ever asked her about her life or sat with her for a tête-à-tête.

One day she narrated a very amusing incident about my father's utter inability to stay away from his wife. The newly married couple had set up life in a small town, away from Mysore. It seems, much to his dislike, my father had to send his wife to Mysore, her parent's place, respecting a tradition in the South which required newly married couples to stay away from each other during the month of Ashad (June-July). The wife would go to her parent's place only to return after a month. This arrangement was designed to prevent the wife from getting pregnant in "Shunya Maas", which is considered inauspicious. The practical explanation of this custom was that if she got pregnant in Ashad, she was likely to give birth to a child in the summer month of Chaitra, not a suitable time for the baby to arrive.

My mother's brother promptly arrived to take his sister to Mysore. My father resented his arrival, but couldn't do much about it. He found it impossible to live without his loving wife. Barely a few days after she left, he mustered enough courage and a sent a fake telegram to his father-in-law in Mysore which read "Self seriously ill. Send Rajam immediately." The worried father, ignoring the tradition, immediately dispatched his daughter to join her husband. When she arrived anxiously at the railway station, to her pleasant surprise, she saw the smiling husband, hale and hearty, on the platform to receive her!

My father was a doctor working for the State department of health. His first wife died young and so he had remarried. When he was posted in Mysore, Krishnaswamy Iyer, the manager of a Dutch taxidermist firm in the city called "Van Ingen &\; Van Ingen", had proposed his only daughter, Rajalakshmi, barely 13 years old, to him. Who was behind this strange alliance? I have no idea. The girl's family was from Madurai. They spoke Tamil and knew not a word of Kannada\; and my father's Tamil was of a special brand with a generous mix of words not sounding Tamil even remotely.

My father belonged to Devarayasamudram, one of the Ashtagram villages. Over the years, the Ashtagram Iyers, who were Brahmin farmers of Tamil origin, but settled in a cluster of eight villages around Kolar in Mysore State, had evolved their own brand of Tamil. Pure Tamil was foreign to my father. I don't know where the wedding took place, and how the doctor and his young Tamil wife spoke to each other. But I'm sure my father's Tamil must have given both of them enough opportunities to share a hearty laugh.

I didn't have the privilege of seeing my grandparents, except my maternal grandmother. My father's father, Nageshwara Iyer, died a year before I was born. There is no photograph of him or of my grandmother. So, I have no idea how they looked. But I have some idea of how my mother's father looked. An old photograph in my collection (see below) shows the family group: the grandfather, grandmother, my maternal uncle, and my mother, taken perhaps a year after her wedding. The infant on my grandmother's lap is Satyan, my eldest brother. In this photograph, my mother, standing behind her father, looks a pretty little nymph of rosy health, with a thick braid of hair neatly combed and a cherubic face exuding childish innocence. In fact, the face did not change much over the years\; one of those faces that time seemed to touch only to brighten and adorn.

(Editor's note: At the editor's request, Mr. Nagarajan has provided this explanation. In the family picture, my mother is wearing the sari in the Mysore style since she was married to a Mysorean. But my grandmother is wearing her sari as Tamilians do, since her husband was Tamilian. Since our family is a mix of both Tamil and Mysore cultures, one can see both the styles in everyday life. My mother also used to wear her sari in the Tamil way on all important occasions like festivals, marriages etc. Even my wife observed the practice. In my wedding picture (available here), my wife is wearing her sari in the Tamil style while my elder sister (Saroja) at her back, tying the Thali, is wearing the sari in the Mysore way. In the picture above, my grandfather, Krishnaswamy Iyer, is wearing a white Mysore peta since he had domiciled in Mysore after shifting from Tamilnadu. When we, as children, spoke to one another at home, we observed this difference. We spoke to one another in Kannada while we spoke to our parents in Tamil! My father's Tamil was bad\; but he had made a sincere attempt to speak in Tamil to please his wife. In the end, my mother's Tamil suffered and that of my father became a mix of Kannada and Tamil!)

During his early years, my father had to serve in government hospitals located in remote areas of the State. When he worked in a place called Humchadakatte, a Jain centre, on the Western Ghats, I am told, I was born there. I remember my mother giving me a vivid description of the day I was born. The midwife of the hospital helped deliver the baby at home. It was raining heavily in the night when I arrived into this world. Perhaps this explains, in a way, my love for rains!

Misty Memories

I have some hazy recollection of my childhood years. The earliest place that remains etched in my mind is a small town with a long name called Chikkanayakanahalli in the Tumkur district of Mysore State. My father was the doctor at the government hospital there. I first attended a pre-school facility called Cooli Matha for a few months, which functioned in a thatched enclosure with a high top. This was actually the parking lot for the temple chariot which had made way for the classroom. The roughly carved wooden vehicle, meant for taking the deity in procession, ignored for most part of the year, stood outside.

There were some twenty of us in the class. The teacher was an old man clad in a dhoti, shirt, coat and a turban. What we didn't like about him was that he had the habit of coming very close to talk to us looking through his "Soda glasses", which made his eyes look larger than they were\; and the devilish stare was frightening. (Editor's note: Soda glasses refers to glasses with thick lenses.)

We had no place to play, but the temple chariot was a good enough substitute. Every morning the entire class sat on the chariot until the bell rang. The bell was a short piece of steel, part of a railway track. The peon would beat it fast with a hammer. Hearing the bell, all of us would jump down from our respective perches and run into the shed, shouting all the way. The teacher would wait with a severe look on his face until silence was restored, and then utter his first admonition of the day: "I have no doubt you were all monkeys in your previous birth." This never bothered us. Some of us took it as a compliment. We thought that if we were Hanumans, we were in fact Gods!

In the evenings, I played with my friends on the road in front of the hospital. We had strict instructions to return home before it became dark. The town had no electricity. There was a street light where we played - a fairly large kerosene lamp hanging from the top of a steel pole. The ‘light man' would arrive at sunset, climb up the pole using a ladder, and light the lamp. This was the signal for us to finish for the day and run back home.

At home, the main light source was a kerosene lamp with the brand name Petromax. Thimma, the peon, who worked at home after the hospital closed, would light the Petromax and place it in the centre of the hall. After returning from play, we went straight to the bathroom, washed our hands and feet, smeared our foreheads with Vibhuti in the Puja room, and then sat in a circle around the Petromax to read and do the homework. A little later, we would sit in a line for dinner in front of shining brass plates with father at the head and the youngest of the children at the end. No unnecessary talk was tolerated.

After dinner, it was time to sleep on the floor on a thick durry, blue in colour, some 15 to 20 feet long. There was an equally long light woollen blanket to cover ourselves. There were thin pillows for each of us. My father had got both the odd-sized durry and the blanket specially woven with his name "T.S. Iyer" at the ends. I don't know what happened to the blanket. But the durry is still there with one of my brothers in Mysore. The high point of the day for all of us was the time after dinner, when we noisily stretched ourselves on the durry and went under the blanket. None of us would go to sleep for quite some time. In the dark, we would chat in hissed tones or tell each other stories or even crack a joke. If we laughed loudly, a shout from the father from his room would immediately restore silence and put us to sleep.

Indelible Images

So much happened in Chikkanayakanahalli during our stay there. But I remember only certain events or fragments of events. I was there during the ‘Quit India' struggle. All that I remember about it is that a group of people - volunteers for the Independence movement - stopped me and my friends as we walked to our school. They snatched the hat I was wearing and threw it on a bonfire of clothes. As the rising flames swallowed my hat, I felt a sense of shock at losing my precious possession and walked back home, crying all the way.

My father celebrated the Upanayanam (thread ceremony) of my eldest brother Satyan here. I remember nothing of this. But an event, less pleasant but life threatening, that has left indelible images in my mind, pertains to the plague which hit the town as an epidemic. Soon reports of people dying of painful lumps, high fever, headaches, chills and extreme weakness started coming in. The district administration swung into action. A temporary township of huts and cottages built of clay, bamboo and thatched roofs came up fast on the outskirts of the town\; and families were asked to move into those structures. The entire town was evacuated. Homes vacated by the people were sanitized, sprayed with poisonous gas to kill plague-infected rats. The hospital too was shifted to the new township. A huge vaccination drive was put into action. My father, assisted by doctors from other hospitals, worked round the clock vaccinating people.

We were among the first to move out and occupy the cottage meant for the doctor. It had everything: a small living room, bed rooms, a kitchen and a bath room etc. Kerosene lamps were hung from the ceiling in all the rooms which the hospital peon, Thimma, cleaned every evening and lighted. Schools were closed indefinitely. For us children, who were unaware of the seriousness of the calamity, the entire exercise was an enjoyable adventure.

But, whenever I think of Chikkanayakanahalli, it is not plague but a fascinating image comes up vividly. One night after we had retired, a loud noise in the sky woke us up. We rushed to the road and looked up. An aircraft was flying very high, which appeared like a tiny star moving from one end of the sky to the other. For the first time I had seen an aircraft flying. I was so thrilled with the experience that I didn't sleep for a large part of the night. They were the Second World War years.

I finished my primary school years at Chikkanayakanahalli. The next place of posting for my father was Bannur, a small Panchayat town close to Mysore. It was here the revered Dvaitha scholar Vyasatirtha (1460) was born. He composed the famous song in Kannada Krishna Ni Begane Baro in praise of Krishna. There was no temple of Krishna in Bannur but there was an old Rama temple, not far from our home at one end of the town. Every evening we played in front of the temple, and as soon as we heard the sound of the bells announcing Mangalarathi after the evening Puja, we ran into the temple to receive the Prasadam, which was generally delicious Puliyogare. The priest was Rama Iyengar, who lived right in front of our house. I made sure he noticed me in the crowd so that a second helping was not denied to me. After play, every evening, my friends and I hung around the temple until this ritual was over.

Friend Dies

I must mention here a very tragic incident that happened one day, when we were playing near the temple. All of a sudden, we heard loud trumpeting of an agitated elephant. Before we realised what was happening, we saw the temple elephant speedily run helter skelter and attack everyone on its way. We ran fast towards the sugarcane fields across the road. One of the boys from our group called Subba Rao suddenly changed direction and began running towards a nearby sugarcane crushing unit. Next to it, there was a large heap of ash formed by burning the dry, fibrous residue after the extraction of juice from crushed stalks of sugarcane. The elephant too changed direction and chased him from behind. To save himself, he ran up the large heap of ash, some 10 to 15 feet high\; and as he climbed, we saw him sink into the smoking hill\; and in no time he vanished. If I were asked to describe the most tragic sight I have seen in my life, it would be this- the pitiable death of a dear friend.

The middle school was located at one end of the town. My friends and I had to walk some distance through a barren patch of land to reach the school. I remember while passing through this stretch, unnoticed by any one, we tried smoking Beedis. We had no money. I stole the Beedis from my maternal uncle's coat pocket and smoked stylishly with my friends as I returned from school. But, thank God, the habit didn't stay long with me.

In the school, my elder sister Saroja and I were in the same class. Probably she lost a year because of delayed admission. She was a very average student while I did well. I sat on the first bench facing the teacher. Saroja was always with her dear friend Nanjamma along with the other girls. I liked Nanjamma. May be, I had a juvenile crush on her. I couldn't talk to her because the boys were not allowed to speak to the girls.

Juvenile Crush

Returning from school, my friends and I made it a point to walk behind Saroja and her friend Nanjamma. We never failed to tease them. In fact, I had even composed a short song in Kannada in praise of Nanjamma to sing in chorus with my friends. It began with Oh, Nanna Puttananji, Neene Nanna Aparanji... meaning "Oh! My little Nanji, you are my purest of pure gold." When we persisted with singing this for a few days, my sister, unable to suffer the ragging of her friend any longer, decided to complain to father. One evening, after he returned from the hospital, he summoned and thrashed me with a stick until I cried loudly. My mother had to interfere and take me away. After this unpleasant development, we decided to ban the song. Years later, during a visit to Mysore from Delhi as a much married man, I ran into Nanjamma. She had come home with her son to see my mother. We greeted and spoke to each other as though nothing had happened.

With less than a year still left for me to complete the lower secondary (7th standard) examination, my father was transferred from Bannur. He didn't want to disturb my studies midway. So he arranged with his friends so that I could stay back in Bannur, attend school and complete the academic year. The arrangement was that I stayed in the home of Ramanna, my agriculture teacher in school, and went to six other homes in the town for my meals every day of the week. I accepted this arrangement for two reasons. I liked my teacher Ramanna\; and I looked forward to the prospect of tasting a variety of food during the week.

I shifted to the teacher's home. Ramanna was a bespectacled Brahmin, short and compact. His wife was slim and tall. They spoke Telugu between them and Kannada with me. They appeared a very happy couple. They had no children and treated me with much love and affection. Sunday was my meals day in their home. The remaining six days of the week, I went to six different homes for food. On every Sunday morning, I was given an "oil bath" by Ramanna's wife. During those days, weekly oil baths were an accepted ritual in the South for keeping the body cool and healthy. Castor oil was used generously to smear the body and, after a while, a hot bath would follow. Sikakakai (Soap Nut Powder) was used to remove the applied oil during the bath. I hated Sunday mornings because of this slimy ritual.

I was short, hefty, dark complexioned (unlike some of my brothers) with a thick growth of black hair. I was a gluttonous eater too. My enemies in the school had nicknamed me Puli Mootte which meant "a tamarind bag". It was actually the nickname of a popular and unduly obese actor, a comedian, in Tamil films. I had fought many a battle with my enemies protesting against this. In turn, I had named one of them Medda, a derogatory term for a squint in Kannada.

Flower Thief

My weekly visits to various homes for meals were not as simple and enjoyable as I had imagined. In one of them, the lady of the house, no doubt, fed me generously, but wanted me to run some errands for her. One of them was to fetch flowers for her Puja every Friday, the day on which I went to her home for food. Much to my dislike, I completed the task by stealing flowers from houses and often from a large garden owned by a Padri (Christian priest) in the outskirts of the town. One day, as I was stealthily plucking flowers after jumping over the compound, the Padri caught hold of me, thrashed me on the cheek, made me do some sit-ups and apologise. I was released after I did all this. I felt very sad and ashamed of myself. Since that day, I stopped stealing flowers and decided to boycott the flower lady's home on Fridays for food. My friends, seeing me hungry, shared their lunch with me at school on that day. Also, I wrote a postcard to my father explaining what had happened. He came to Bannur to look me up and sorted out the problem. In addition to Sundays, on Fridays too, I began messing at Ramanna's place.

Ramanna was among the most sought after teachers for tuition by parents for their children. Every evening he held classes at home for a number of boys and girls including me. The seventh standard examination then was a ‘public exam' conducted by the education department at various centres in the State. Bannur was not one of the centres. We had to write the examination, spread over a few days, at a bigger town called T. Narasipur, a few miles away. Ramanna escorted all of us to Narasipur for the examination. We travelled in two bullock carts and, on the way, halted for the night at a place called Sosale. We stayed there at the Vyasaraja Mutt on the bank of the river Kaveri. The Mutt looked after us very well, and there was a special meal cooked for us at night. In the morning, after a bath in the river, and blessings from the Swamiji, we continued our journey to T.Narasipur. The examination was conducted at the local school. When the results were announced, it was heartening to see my name at the top of the list. I had passed the examination with distinction.

When I was in Mysore on a visit, years later, with my wife and children, Ramanna and his wife, a ripe old couple, came to see me. It was an emotional and an unforgettable meeting. They were delighted to find me well settled in life. I never met them again. In life, we come across many people who play a large part in shaping our lives. They appear at the right time in the right context as characters in a play and depart after they have played their roles. Do we look back and remember such people? Can I ever forget Ramanna or for that matter the Padri whose slap on my cheek changed my entire character?

© T.S. Nagarajan 2012

Add new comment