Ramanna, 105, “Not out” by Bapu Satyanarayana

Category:

Bapu Satyanarayana, born 1932 in Bangalore, retired as Chief Engineer, Ministry of Surface Transport. At present, he is the presiding arbitrator of the Dispute Adjudication Board appointed by the National Highway Authority of India. He lives in Mysore, and enjoys writing for various newspapers and magazines on a variety of subjects, including political and civic issues.

Editor’s note. Ramanna passed away after this article had been written. The manner of his demise was such that it is appropriate to declare him “Not out.”

The Centurion

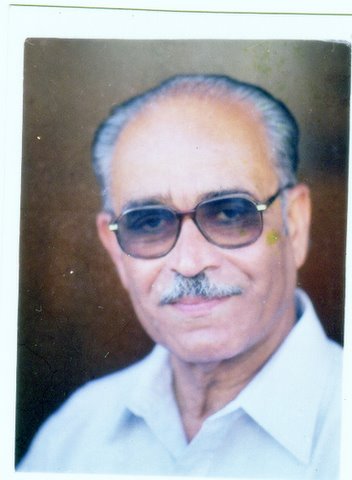

In 2007, in his 105th year, my father, Ramanna, bridges two centuries.

While many people younger than him suffer from Parkinson’s disease or senility, he has firmly kept illness at bay, and does not take any medicine. Even now when somebody enquires about his welfare, he has no hesitation to say that he is in perfect health! Of course, he has some problems with his eyesight and hearing, but he takes them in his stride. Some of the old fire has dimmed and sometimes his memory fails him, but when his family prods him and the mood catches him, he can recall things with surprising clarity. On top of it, he is a connoisseur of good food and relishes it immensely.

My father is well read both in Kannada and English. The felicity with which he wields his pen in both the languages is remarkable. His writing flows easily, and it is a pleasure to see how neatly he would write in perfect straight line and with bold and firm strokes. For this story, I have relied on my father’s Athmakathe (story of life), which he recorded in Kannada on lose sheets at various times since 1992 and it contains a fund of information. (Editor’s note: A sample page is attached at the end of this article.) Even for us family members, it was simply astonishing that in his 90th year he could recall with amazing clarity details of many incidents that happened when he was six years old.

How did he do it? He gives three reasons: zest for life, rosy outlook on life, and an indomitable willpower. When he was young, he read an article, ‘Persistency of youth’, which has kept him going even now. He loves to meet young people. When he was in his 90s, I suggested to him that he go to the nearby park where he could meet people in their 70s and 80s. He ridiculed the idea, saying “I do not want to mix with such old people!”

His habit of walking has surely helped. He used to walk for 10-15 km every day, going around the neighbourhood, calling on people known to him. This came to a stop in 1999, when he tripped and broke his hip joint. The surgeon, Dr. Nityananda Rao, who operated on him at BM Hospital, remarked that his bone strength was that of a 60 year old, though he was 96 year old at that time. Since then, he is using a walker.

He was always Spartan in his habits and very independent. His needs are few, three sets of jubbas (kurta), white dhoti and white handkerchiefs – he always liked white clothes. He was immaculately dressed in a white khadi jubba, with golden buttons and kacche panche (nine yard dhoti worn in a graceful manner) with all folds properly in place - even at this advanced age he pays attention to this habit. A tall figure, he would walk erect, with a royal gait that made a great impression on all.

Into his 97th year, and until he fractured his hip joint, he used to make his own bed. Then he would do light exercise and practice what he called Mahesh Yogi’s breathing exercises and continued it fitfully later on. He is very strict about timings in keeping appointments. He feels restless if he does not have his watch, which he consults and announces that it is time for lunch, evening coffee, etc. Though he has mellowed now, his famous Durvasa temper still surfaces occasionally.

He can easily mix with people and engage them in conversation – we used to joke that he can make even a stone talk to him! He revelled in mixing with people and socializing – that was his style. He would attend lectures and always sit in front row. He would get up and ask questions. He often told my siblings and me not to be shy, and encouraged us to participate actively in public meetings. He had a set of friends, whom he would meet in a club to play a card game called ‘28’, which was very popular in his days.

My father has insatiable curiosity. On March 19, 2002 when the Star of Mysore, an evening daily newspaper, interviewed him, he talked about cloning, computers, and many other modern developments. He would keep himself abreast of current events, and would cut out newspaper articles that interested him. Until recently, he would watch cricket and tennis on TV, sitting for hours together into the early hours of the morning.

He is very fond of being photographed and even at this age if somebody says he would like to take a photograph, he would perk up and sit properly adjusting his clothes. Probably, he is the most photographed person in our family. His regret is that these days he can not join in conversation because of poor hearing. But it has not in anyway come in the way of reading newspaper or any reading material kept by his side.

Growing up

Born on 17th March 1903 in Kikkeri hobli (a cluster of villages) in K.R. Pet taluk (in Mandya district, Karnataka), he was named Ramanna. Initially, following his father, he used Bapu as a prefix, which he discarded many years later. My father has recorded the history behind this prefix in his diary. It appears that my ancestors were in charge of security for a fort or fort-like building, and got the title Bapu in appreciation of their service.

His early schooling was first in Kikkeri and then in Hassan, a district capital, where he stayed alone in a dingy place, crawling with all sorts of insects like bugs, cockroaches, scorpions and even snakes. With only kerosene lamps for lighting, it was quite brave of my father to have stayed alone there as a schoolboy.

His Headmaster was R.V. Krishna Swamy, father of R.K Narayan, the world-famous author, and R.K. Narayan’s older brother, R.K. Pattabhi, was my father’s classmate. Maths was my father’s weakness. In his final examination, he says he got only 22% marks in maths, and 33% were needed to pass. Since his school’s average in maths was 22% and the State average was also only 22%, he was deemed passed. It was a big sigh of relief for him. He was glad that the great burden was off, and he was done with maths for good!

During the time he was a college student, his talent for Bharata Vaachana (reciting incidents from Mahabharata in poetic form) and Sugma Sangeetha (light classical music) won him many prizes. He acted in plays, and recalls with great pride and relish his part as Melanayaka in Ashwatthama (a thought-compelling Kannada tragedy). He can recite his lines even now from this and other plays in Halegannada (Old Kannada, dated 900-1,200 CE) with impeccable pronunciation.

He had a powerful voice, and in an era when there were no microphones available, he could spellbind his audience. He was a favourite student of B. M. Shree, a very influential Kannada author and translator, and even now he is never tired of repeating Shree’s name with great reverence and admiration. He regularly donated money to the B.M. Shree Smaraka Prathishtana (memorial institute) at Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs, Bangalore until 2004. During Shree’s Silver Jubilee Celebrations, he gave a command performance, which moved the Vice Chancellor, Brajendra Seal, to remark that it reminded him of Pindaric ode, while Principal Rollo addressed him as ‘silver tongued Ramanna’.

He could sing from Shree’s English Geethegalu, a book of translations\; his father’s favourite piece was Anathe (Bridge of Sighs by Thomas Hood). He says audiences were moved to tears when he sang this sad song of a jilted lover ending her life by jumping into a cold river. In fact, my father was responsible for motivating my sister H.R. Leelavathi to take up singing. It was a unique occasion in October 1951 when father and daughter sang from Shree’s Geethegalu together in Mysore.

After his BA, he studied Law in Madras. He recalls with pride serving as the Whip of the Kannada Bhrathru Sangha (which brought together Kannadigas of Law College, Christian College and Loyola College), founded by his friend D. Ramaiah. He still remembers the names of all the office bearers.

He got married in 1924, while he was still studying for his BA in Maharaja’s College, Mysore. He says that he had a love for arts, literature and music from a young age. He has recorded that he had read Bana’s Kadamabari (a Sanskrit classic, translated into Kannada), when he was 10 or 11 year old\; when he was 90 years old, he could still recite many stanzas from it.

In Mysore he was a member of Bidaram Krishnappa Rama Mandira, a musical institution, and regularly attended music programmes with his wife (my mother). My father records that he had heard Veene Sheshanna, a famous veena player who died in 1926. He liked to sit in the front row and always went with my mother. They were inseparable and would go for evening walks together. Ever since my mother died on Oct 31, 1970, he has adjusted himself to a lonely life. After her death he has written about her, praising her gentle nature and how patiently she put up with his fiery temper.

Congress follower

He was a very staunch follower of the Congress. He always used to wear khadi dress and occasionally sport a Gandhi cap. He records that when he was a school student, a well-known local Congress leader, Mr. Mudvedkar, had come to give a lecture and collect money for the freedom struggle. He rushed to hear him. Mudvedkar’s speech was electrifying. Many in the audience gave their precious possessions on the spot, including gold ornaments. One particular incident is deeply etched in his memory: an old lady named Kaveramma gave a silver cup to Mudvedkar, who drank water from it, saying that the Swaraj movement is gathering momentum.

There was also a bonfire for burning the foreign goods as a result of the call given by Mahatma Gandhi. Everybody was throwing their dresses to the bonfire to the wild cheering of the crowd. My father also threw his new shirt. The crowd was chanting continuously, “Haku benkige urili dhagha dagha dharisu khadi pavithravu! (Throw it into the fire, let it burn fiercely, and wear the sacred Khadi!)”

One high point of his life was Gandhi’s visit to Mysore in 1936, when he addressed the crowd in Town Hall. He spoke in Hindi, which was ably translated into Kannada. Shouts of “Gandhiji ki jai!” and “Congress ki jai!” rent the air.

When the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) visited Mysore in 1922, great preparations were made to receive him with pomp and honour. The Prince’s procession passed by the side of the hostel on Sayyaji Rao Road, where my father lived. However, he was such a staunch Congressman. He records that he stuck to his seat, and refused to go out and join the crowd to see the Prince.

Similarly, when Sir Mirza Ismail was invited to a function at Mysore University, my father refused to attend, even though he was to receive prizes in running and cricket ball throw. Ramanna considered Mirza to be anti-Congress.

While Ramanna was studying in Madras, he participated in the salt Satyagraha on March 12, 1930 in Triplicane beach, and narrowly escaped being caught by the police.

In keeping with the ‘wear khadi’ spirit, Ramanna got a charkha (spinning wheel) for my mother with lot of cotton to spin khadi thread. With this hand-spun cloth, he got four jubbas (kurtas) made. He kept two for himself, and presented the other two his father-in-law, a senior civil servant. Ramanna persuaded him to wear them, which was quite a daring act as it symbolised affinity with the freedom struggle. It seems that he caved in because he did not want to offend his son-in-law.

Ramanna gave a takli to another relative. A takli consists of a metal rod with a heavy ring and is also used to draw the thread from cotton. It requires more time and patience than a charkha, but its advantage is that it is easy to carry it with you when you travel.

His attachment to the Congress was total. But, later in life, he got disillusioned with the Congress and presently he is a follower of the BJP.

In his Athmakathe, he succinctly puts it in these words:

* Then: Congress is a name to conjure with its wonderful influence. Even the child in the womb was affected by its influence (like Abhimanyu).

* Now: Congress is a byword for ridicule. Politicians are only attracted by the power and money to the utter dismay and neglect of masses, a shameless universal laughing stock.

He is a great admirer of Atal Behari Vajpayee, and until two years ago, his prayer included a plea to God for the success of BJP.

Adult life

After earning his law degree, he worked as an apprentice for a year, and then started his own practice. He writes that he was dead against the Evidence Act. His complaint was that the witnesses, instead of giving evidence of what actually transpired, were tutored to repeat what the lawyers had told them to say. This thoroughly disillusioned him, and he gave up law. In 1939, he joined Mysore Silk Filatures, from where he retired as factory manager in 1958.

As a factory manager he was quite popular. I remember a boundary wall with a high gate surrounded the factory while the building proper was far inside. My father often took me with him during his nightly visit to the factory to check. Invariably, there would be no guard at the locked gate\; his method of calling the guard was to join the thumb and index finger at the tip of his right hand and put it below his tongue turned inside and blow out a shrill whistle. This would make the guard come running down to open the gate for sahebru (big boss).

Ramanna always tried to give help to any who asked for it, such as in getting a job in the factory or in terms of money. In fact, when my (late) brother H.R. Bapu Seetharam was employed in BEL, my father used to recommend to him persons for employment, which they usually got. I have met many persons who have told me that they are grateful to my father for getting them a job.

In our home, we had several persons coming on different days for their meals under the varanna system, and many of them later prospered in life and occupied prestigious positions. (Vara means week and anna means cooked rice in Kannada. Varanna is a system in which poor students come to a home once a week, or even more frequently, for their meals. Lately, the system has practically disappeared.)

Unfortunately, when he retired, Ramanna and a few of his colleagues were left high and dry without any compensation or gratuity due to a mischief played by one of the clerks. It was due to caste hatred, which still haunts India today. My father, investing his own money, filed a writ petition and continued to fight for several years. Nothing came out of it except one of his colleagues got some money. When Ramakrishna Hegde became Karnataka’s Chief Minister (1983), my father made fervent appeals to him, but without any change in his situation. In fact, even five years ago, he said that we should keep the fight going! One of his younger colleagues, Mr Sundara Rao, who is 88 years, is still fighting.

He has been frugal and careful about spending money. How else he could have educated us three brothers and sister from his limited income? He used to say, “I have nothing of wealth to leave you but I will spare no effort to educate you.” We are enjoying the fruits of his efficient management of his finances. Incidentally, these included a monthly pension of Rs. 11 that my mother received after the death of her father, who was an Executive Engineer when it was a senior position. And, of course, there were the gold ornaments that my mother received from her parents when she got married – they served to pay for our education.

In Ramanna’s home, at whatever time people dropped in, they would be served delectable coffee, made in the old-fashioned way with a cloth strainer, unlike today’s filters, and served with savouries like kodbale or chakli. My father’s favourite dishes were thalipittu (Akki roti) and menthyada dosa. My mother, the only daughter of a high ranking civil servant, had come a long way to adjust to the simple living in our family. She learnt cooking the hard way, and was known for her excellent preparations made quickly whenever people dropped in at odd hours without notice at our home, which was quite often as my father had many friends.

He was fond of writing to famous people whom he liked, whether it was the Chief Minister or a Minister of the State or Centre, and they usually replied to him. He was very happy that Amin Sayani, the presenter of Binaca Geetamala, a very popular radio programme in the 1950s and 1960s, replied to the long letter that Ramanna wrote to him. He also got a letter from P.V. Narasimha Rao, who went on to become India’s Prime Minister, when my father asked him for a copy of his talk delivered over the radio on the subject of a comparative assessment of Nehru and Lal Bahadur Shastri – both of whom were Indian Prime Ministers – after Shastri’s demise.

He was also fond of writing in Kannada and English newspapers on a wide range of topics. His favourite newspapers were the Indian Express and Prajavani.

Once my siblings and I had completed our education, we dispersed to various parts of India, in search of good job opportunities. We all used to write letters to him either in Kannada or English, and he kept our letters carefully. Our problem was that he would reply the same day that he received a letter, and he expected the same promptness from us – otherwise he would become restless.

Prayers

Though in his formative years in Kikkeri he participated in Ramanavami and other religious functions in the temple, I have not seen him sitting for long time in the prayer room. However, he did learn Sanskrit shlokas and used to recite shuddha bramha (two line stanzas telling the story of Ramayana popularly sung in Kannada), and was punctilious about observing some religious functions such as upakarma.

In his old age, his daily prayers have acquired a greater fervour. After reciting the usual Sanskrit shlokas, Pujyaya Raghvendraya, etc., his prayer would end with “Ishwar Allah tero naam, subko sanmati de Bhagwan”, one of Mahatma Gandhi’s favourite prayers. Of course he did not forget to pray for the health of all family members, and for complete health for himself. Lest God would forget, he would name every part of his body!

“Not out”

My father reached his heavenly abode peacefully on October 23, 2007, with his three surviving children (two sons and a daughter) at his bedside. We had a sense that his demise was coming because he had not spoken for the past ten days, and from October 19, 2007 onwards, our doctor could not get any pulse, hear Ramanna’s heartbeat, or measure his blood pressure. Yet, he was breathing rhythmically and evenly – even our doctor was amazed.

In his last four days, Ramanna had practically no food or drink, and his eyes were mostly closed. But, whenever we spoke to him, he would acknowledge it by nodding his head. Until the end, his grip was firm. When some of our relatives came in the morning of October 23, and I asked him to shake hands, he squeezed their hands like a normal strong person.

On October 21, when my sister told him that we are all at his side, he surprised us by saying, “Anandamaya (supremely happy).” When I mentioned this to one of our friends, he said that maybe Ramanna was already in astral world of fifth kosha called Anandamaya kosha!

On his last day I was able to make him drink half a cup of coffee and eat a bit of a biscuit. When I asked him to eat something more to gain some strength, he did Pranams with both of his hands, and gestured outwardly with both hands, indicating that he is going away. He was repeatedly doing Pranams, as if to someone who was not present in the room. I gave him photos of Mata Amrithananda Mayi and Lord Venkateshwara of Tirupathi, which he used to look at frequently, and he held them in a firm grip.

Towards the end, we could see his breathing gradually subside, with only a slight movement in his neck. I gave him Ganga jal (water), which he swallowed, and then his life gently ebbed away.

His face was serene, as if he felt he was “Not out”.

Annex

A sample page from Ramanna’s Atmakathe, written in 1992. The teacher referred to here is Mr. M.V. Gopalaswamy, a well-known professor of psychology, who in 1936 established India’s first private radio station, which he named Akashvani, in Mysore.

Translation

5) Fifthly, a new experiment was taken up. It concerns ‘planchet’, a small contraption which consists of a wide almond-shaped wooden plank, about a quarter inch thick. We have to observe and follow its movements by placing our hands on it. It is approximately three inches in height with lead sticks at the bottom. The object is to study the pattern left on a wide paper on which this simple contraption is placed and moved with the hands. For this my teacher had detailed a few of us at Margosa Lodge when I was staying in an adjacent college hostel. I used to go and take part in the experiment. However, the usefulness of this experiment was known only to our teacher. But I did not venture to find out about its usefulness. P.T.O.

© Bapu Satyanarayana 2007

Add new comment