Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

An American Boyhood in British India

Category:

Stan retired as a university professor, specializing in the cultural and social history of the Indian sub-continent. He speaks in an English reflective of his boyhood in India. This made lectures easy to understand for his Pakistani students at Forman Christian College and Punjab University, Lahore. Stan describes his Urdu proficiency as "serviceable."

Editor's note: This story is excerpted, with permission, from Farewell the Winterline: Memories of a Boyhood in India by Stanley E. Brush, Chipkali Creations • 192 Ezra Avenue • Santa Rosa CA 95401. An online version of the book is available at www.farewellthewinterline.com.

In 1998, in the foreword to his book, Stanley wrote:

So much has changed in India over the past seventy-three years that the period before and during World War II, its disturbances, dislocations, and precipitous end of British rule seem like scenes in a distant drama, ever receding over the horizon of living memory. The details are obscure, the colours have faded, the sounds are barely audible. As the generation of those who were there leaves the stage, the details go with it and are lost forever.

This memoir is a record of my life and times, a person who was there, the son of American missionaries and a student in an American-sponsored boarding school in the Himalayas. This is not a political history, nor is it a history of missionary work in India. It is a tale in which I have tried to re-imagine how I felt and saw things then. The focus is personal, and somewhat narrow, just as my life was as a boy and teenager.

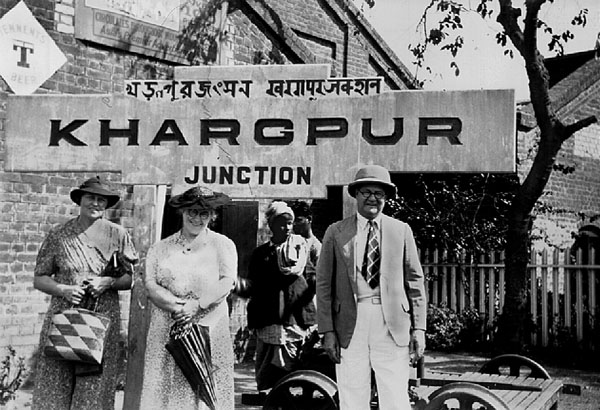

![]() I was born shortly before midnight on November 8th, 1925, in the first floor bedroom of the American Baptist Mission bungalow in Khargpur (now Kharagpur), Bengal, India. British India, as it then was.

I was born shortly before midnight on November 8th, 1925, in the first floor bedroom of the American Baptist Mission bungalow in Khargpur (now Kharagpur), Bengal, India. British India, as it then was.

My mother, Helen Irene Humphrey Brush, wife of the Reverend Mr. Edwin Charles Brush, was attended by a midwife, Nurse Huston-Avis. She was a medical staff member of the Bengal Nagpur Railway Hospital, an institution located just a few blocks from the American Mission.

The British Indian town of Khargpur sprang up when the location was selected by the Bengal Nagpur Railway builders as the separation point for the trunk lines from Calcutta, north through Midnapur to Asansol, south along the coast through Cuttack to Madras and westward through Jamshedpur and Nagpur to Bombay - India's west coast "Calcutta," in my fiercely parochial opinion!

Khargpur Junction was a magnificent station with red laterite gravel open-air platforms, which, we firmly believed, were the longest platforms in the world! Acres of railway workshops were built, big enough to build and repair rolling stock and the hardware necessary to keep a railway going. Mammoth turntables to handle steam locomotives with tenders attached and sheds in which these and other equipment such as "bogies" (passenger coaches) and "goods wagons" (freight cars) could be dismantled and repaired were major features of these shops. Everything was tied together in a maze of tracks, switches, signals, crossings, gates and gatekeepers, underscored by the rumble of rail traffic, heavy machinery, the clanking and laboured breathing of engines and sounds of whistles. The railway was clearly the centre of life in Khargpur.

Khargpur's population was residentially segregated in the usual British fashion. The English lived in large shaded bungalows set back from the streets, surrounded by gardens, and on the side of town away from the trains and workshops. Their houses faced the maidan (parade ground) and were close to the BNR European Officers' Club with its swimming pool and golf course. Anglo-Indians (the category for persons of mixed European and Indian descent, be it ever so remote or slight) lived in shaded and gardened bungalows of smaller size along the streets of the rest of European Khargpur within easy reach of their community centre, the Anglo-Indian Institute. Here, twice a week, Hollywood movies were shown. Scattered throughout this part of town were the servants' quarters occupied by Indian household employees.

The usual domestic corps consisted of a khansaman (cook), bera (general household servant or bearer), ayah (nursemaid and housemaid), mali (gardener), chawkidar (watchman) and others. The number depended upon the social standing and income of the employer. The rest of Khargpur's citizens, a population of great diversity from many parts of India, lived on the outskirts of town or on the north side across the tracks in and around the bazaar, called the Railway Market, in residences that housed mainly railway employees and their families. Places unfamiliar to us from the "other side".

Khargpur was only one of the many mission "stations" in the American Baptist Bengal-Orissa field and the work there was only part of a wide-ranging network of religious, educational, medical and other humanitarian enterprises that engaged the devoted attention of a diverse company of workers, both foreign and local.

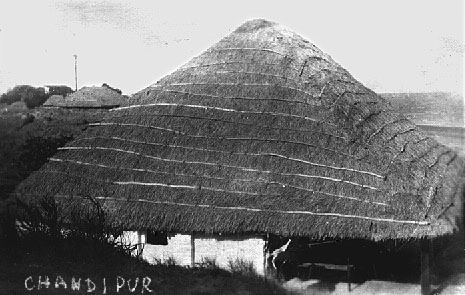

Our vacation spot on this coast was Chandipur. In addition to the fishing village a mile or so away there were three mission-owned beach "bungalows" there standing bravely behind low thorn-infested sand dunes. Far to the south, on the horizon, was a Royal Indian Navy gunnery range where the ordnance boomed away on many afternoons in an awesome manner, raising waterspouts far out to sea. My earliest memories of salt water, sand, surf, mud flats, fish, fishy smells, crabs, mosquitoes, prickly cactus in the sand and snakes are associated with Chandipur. These last mentioned were unwelcome tenants, sometimes living in the thatch roofs of our beach houses. Everyone kept an eye out for them. When discovered, which wasn't often, the snake would be killed or driven far away. Contrary to the American perception, encounters with snakes were not an every day experience.

Balasore and Chandipur figured in an unforgettable bicycle adventure in my high school years. During one winter vacation, my friend Gene and I decided to ride to Balasore, a distance by road from Khargpur of some eighty miles.

After obtaining parental permission and making the necessary arrangements in Balasore (as paying house guests-a standard practice among missionaries all over India), we left-I on my Phoenix, Gene on his Raleigh-early in the morning, in high spirits overflowing with conversation and laughter. As the sun rose higher, the road stretched out endlessly. The day wore on into the afternoon. Talk ceased. It was hard work!

The Subarnarekha River, two-thirds of the way to Balasore, offered some relief. Here the ferry, as they were at many unbridged river crossings in the region, was a country-made, sturdy, flat-bottomed boat with narrow planks on each side of the deck from fore to aft. The boat was propelled by the ferryman. Starting at the prow, he would thrust a long bamboo pole into the river bottom and then push the boat through the water by walking his way to stern. The river was wide and shallow with a slow current. The beauty of the vista and the cool air on the water were inspiration enough to take us through the remaining miles.

What we didn't realize was that the return journey would be into a headwind all the way! Camaraderie on the return was soon forgotten as we reached for strength to keep on pedalling. We lost and regained sight of each other while we rested under shade trees or forged way ahead. Arriving home in Khargpur separately after dark, we later agreed that we wouldn't be doing that again for a while!

The most exotic town within the geographical boundaries of the Bengal-Orissa mission field was Puri. The Brushes went to Puri not as pilgrims but as very interested visitors.

Three experiences stand out:

First, outside the temple complex along the temple cart road, the great gathering of beggars suffering from some of the most startlingly disfiguring diseases known to humankind. Massive goiters, mutilating leprosy and hugely swollen legs and genitals caused by elephantiasis. A man I saw had a scrotum so large that he carried it in a small cart, which he pushed along in front of himself.

Secondly, our condition of "ritual impurity" which closed the temple itself, to us as non-Hindu polluters and to other non-Caste Hindus. We lived with this "pollution barrier" in other situations, for example, in a quiet way when dealing with Hindu food vendors in the bazaar. The rule was never to touch the hand of the vendor, even inadvertently, when making payment or receiving change, or to touch the tray or vessel holding the food. Still, it was a shock to be declared "untouchable" so publicly.

Thirdly, the surprise of the display case in the outer courtyard, which contained images of the familiar gods and goddesses and a few others, including a statue of Jesus. Our guide explained that Hindus revere all the great historical spiritual personalities and uncounted others whose names we don't even know. I can still recall him saying that for Hindus there are thirty-three million gods! That was something for me, as a determined young monotheist, to ponder!

Two hours by mail train (the fastest non-stop service along this portion of the line) from Khargpur lay the great railway terminus, Howrah Station, and the city it served, Calcutta. All day excursions to Calcutta occurred at least once a month, but usually more often.

In Calcutta, most of our shopping was done at the department store of Whiteaway and Laidlaw on Chowringhee Road and at New Market, a covered market with hundreds of stalls where everything was available. Venturing into New Market was a shopping experience unsurpassed for the bargaining encounter of customer and merchant, both exhilarating and exhausting! The crisp and aromatic Firpo's Restaurant was the place to have lunch topped off with a dish of Magnolia ice cream, the only brand deemed safe to eat.

At the end of the day, there would be the just-in-time dash in a horse-drawn Victoria, fighting heavy bus, bicycle, rickshaw, pedestrian and animal traffic, across the Hooghly River pontoon bridge, to Howrah Station. Once there, red-shirted porters would take our packages and lead the way through the crowded concourse and waiting hall to the platform where our train, either the Bombay Mail or Madras Mail, waited. They would find our reserved first class compartment, stow the packages inside and then complain vociferously about the payment, pointing out that the established rate printed on their shirt patches was not correct. The conductor/guard, in a dark blue uniform with brass BNR insignia, wearing a white topi, would blow his whistle and wave a green flag. With a long return whistle from the engine, the train would begin to move and with increasing speed leave the busy platform, clatter across the railyard, pass the signal cabin and rush into the smoky dung-fired dusk toward Khargpur and home.

Woodstock school

Dad and Mother were faced with the serious problem of schooling for John, my older brother, during their first term in India, and for Frances and me after they returned to Khargpur in 1931. There were several options, such as using a correspondence course at home or sending us away to a boarding school in India. Another was to send us to the "States" and arrange for our schooling there. That was the one chosen by the Amstutz family (American Methodist missionaries in British Malaya) for their young daughter, Beverly, whom I later married. Of course, Bev and I are indebted to her parents for bringing her back with them from furlough in 1939 and sending her to Woodstock School in India.

Making a school decision for children involved balancing calculation, sentiment and myth. The myth was a widely held belief that the tropics (before air-conditioning) were unhealthy for white adolescents, especially girls. They mature early like "hot house flowers," is the comment Beverly remembers hearing. That being the case, it was thought by some parents to be wiser to leave young children in America or send them back as early adolescents from overseas.

A temperate climate was available, however, in India in the mountains, where the foreigner-friendly atmosphere was celebrated by dispensing with the bothersome topi. Here the British authorities built dozens of towns at elevations of 5,000 to 7,000 feet above sea level. They were places in which to locate summer offices, military cantonments and hospitals, holiday resorts - and schools, run mostly by church-related organizations along the lines of English boarding schools.

Dad and Mother wanted to find one with an American curriculum and a Protestant orientation. Three qualified. They were Kodaikanal (pronounced cody-kanal) in South India, Mt. Hermon School in Darjeeling, in the Himalayas of Northern Bengal, and Woodstock School in Landour (pronounced lan-dower), in the Garhwal Himalayas of the United Provinces, north of Delhi.

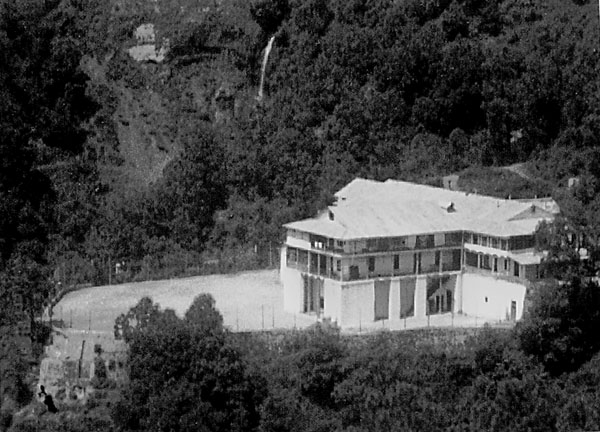

They chose Woodstock. It was a school that offered both an American curriculum and, at the high school level, the Cambridge examination curriculum preparatory for admission to British or Commonwealth universities. The total enrolment from kindergarten through high school (10th Standard -equivalent to 12th Grade) was three to four hundred.

The Woodstock community was international. It included Americans, Britishers, Canadians, New Zealanders, Australians, Anglo-Indians, Indians and others, but was predominantly American. Classes and student activities were coeducational, which was unusual in India at that time. Boarding facilities (non-coed, of course) started at the Third Standard and continued through Tenth Standard.

Naturally, students who started out in Kindergarten (called KG in India) or First Standard and moved up together as classmates through high school established bonds like those of a "second family." I knew my boarding school classmates better than I knew my brother, John. As we grew older, we preferred to be with our friends in the dormitory rather than to be out-of-touch living with parents and attending school as day scholars. This was true even though the food at home was better and restrictions less onerous than in the Boys Hostel!

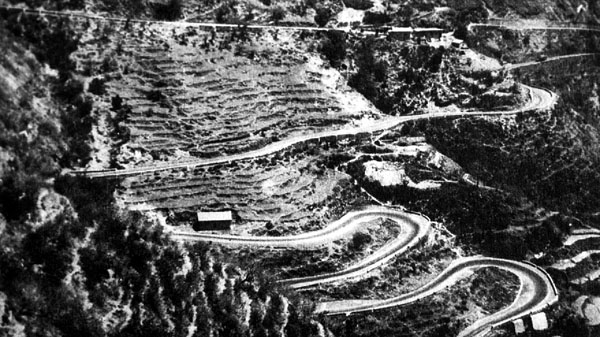

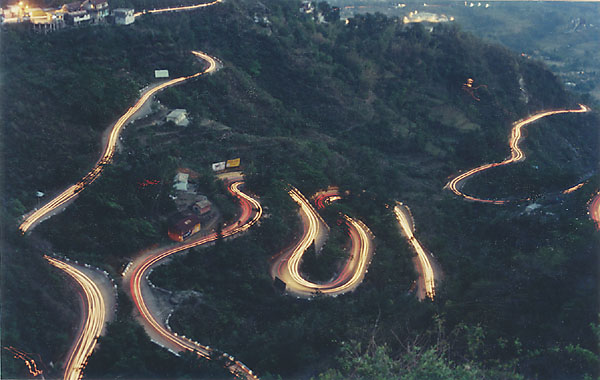

We got to Landour in "school parties" made up of students and an adult escort travelling from various outlying points in India and abroad, such as Rangoon and Singapore, to the Mussoorie/Landour railhead at Dehra Doon (alt. sp. Dun). From Dehra the climb to Mussoorie was accomplished by bus over a remarkable motor road.

Completed in 1929, the road was a triumph of mountain highway engineering but not one for the faint-of-heart. It featured 25 climbing hairpin curves and 275 right-angle turns, some of which were blind corners requiring repeated squeezing of the rubber horn bulb. It ascended about 3,500 feet in twelve miles from the edge of the Doon Valley at Rajpur to the bus terminal at Sunny View (later moved to Kincraig) just below Mussoorie. Passengers subject to motion sickness sat in the rear or up front behind the driver, but, in either case, by open windows.

The last three somewhat breathless miles to the Landour Cantonment beyond and above Mussoorie were completed on foot, with porters carrying our heavy luggage on their backs. Situated at the top of Landour ridge at 7,400 feet above sea level were barracks and a military hospital, along with a few private houses, a small bazaar, Kellogg Church and a Christian cemetery. All were accessible from a pedestrian road called the Chukkar running just below the crest.

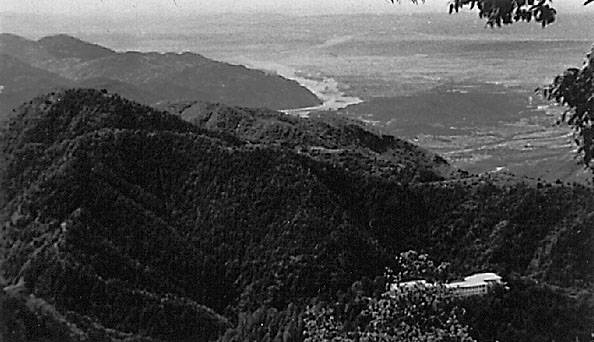

The Landour location was spectacular. Northward there were views of the snow peaks around the sources of the Jumna and Ganges rivers near the Tibetan frontier. Southward the flat expanse of the Doon Valley lay almost at our feet, bordered in the middle distance by the Siwalik hills. Beyond them, visible on clear days and nights, were the receding terrain and twinkling lights of the north Indian plains. The forests of silver oaks, horse chestnut trees, long-needle pines, deodars (Himalayan cedars) and rhododendron\; the lush grasses, wild flowers, ferns and mosses\; the immense valleys and sweeping vistas of range after range leading up to the snows were breathtaking. The changing seasonal drama of towering cloud formations above or the endless ocean of monsoon clouds below broken only by mountain "islands\;" the swirling mist\; and shattering lightning, thunder, hail and rainstorms sending torrents cascading down the mountain, sometimes taking whole pieces of hillside, road and portions of buildings with it, thrilled us to the core. The acrobatics of long-tailed langur monkeys with a taste for roof-running and garden flowers\; the ravine obligato of the Himalayan whistling thrush mingling with sounds of a gurgling stream\; the Lammergeyer vulture riding the wind on a nine-foot wingspan at our eye level, yet a thousand feet above the valley below\; the fantastic airborne beetles of rainy season nights ricocheting off window panes and outside lamps\; yes, even the leeches, spiders and scorpions-all left an indelible imprint on us at Woodstock of how beautiful and awe-inspiring the natural world was!

For students, school party travel was an adventure\; for the escort, a stressful responsibility. We occupied a large reserved inter-class or third class compartment on the Dehra Doon Express, upward bound, or the Howrah Express on the return. The train left Calcutta late in the evening, travelled up the Gangetic plain all the next day, past Gaya, Benares and Lucknow, all of which were historic cities of great cultural significance but of little interest to these youthful barbarians on their way to school.

Lucknow is where we would pile off the train for a preordered supper in the first class refreshment room while the train completed its forty-minute halt. The meal was usually a delicious offering of mulligatawny soup, rice, chapatis and curry, a custard dessert and tea. Dawn the next morning found the train passing beyond Hardwar into the Doon Valley where the forest came down to the tracks and where peacock calls could be heard and deer seen as we rumbled by. From here, above the trees, the Himalayan foothills came into view. This was the signal to roll up our bedding into our canvas sleeping bags called bisters (from the Hindi word bistar for bedding), shut suitcases and gather up personal possessions for the arrival at Dehra Doon and transfer to Mussoorie-bound buses.

These early Woodstock years from 1932 to 1937, when John graduated, were for me a period of emerging self-awareness and clearer recollections. The birthday "harvest" of those Novembers produced the numbers seven through twelve. The year 1932 found me starting briefly in Upper Kindergarten, then moving before the end of March into Standard One. At the end of 1937, Standard Six was over and done with.

Hostel life? Not too different in many respects, as I discovered later, from basic training life in the United States Army.

We were grouped by class in dormitories, so we "grew up" together over the years. Metal double-decker beds with latticed metal tape as mattress supports stood in ranks along the walls. Low dressers without mirrors ranged down the centre of the room. Almiras (clothes' closets) stood against the walls between the beds. Our own tin trunks were kept under our beds for personal storage space. The normal school day began with a wake-up call giving us half an hour for washing, dressing and making beds before appearing for breakfast. Twice a week the preparation included a mandatory hot soap shower. First came the wet-down, then the soaping, head to toe, front and back, then waiting-in-line for the master-on-duty's inspection to make sure soap had actually been applied everywhere, then the rinse.

Hostel food was basic unadorned English fare filtered through the institutional sensibilities of the Indian kitchen staff. Our favourite was the curry and rice served once a week. The chocolate pudding wasn't bad. The Sunday raisin buns were delicious. Tea was served with milk and sugar. There were also the famous Woodstock "bicks," hard, plain baked crackers that were highly durable. They could be saved for future consumption or traded as a kind of currency for other valuables. The nearest I ever came to murder was the day I discovered Charles Root, a dorm mate, with his hand under my mattress in my hoarded bick supply! Friends pulled me away from the fight, out-of-control and shaking with anger.

Weekends brought a welcome break in the class routine. Saturday was laundry day. It was collected by school dhobis (laundrymen) who lived with their families in a settlement called the Dhobi Ghat in the saddle between the base of Landour and Witch's Hill along the stream they used for their work, which they did by hand, of course. Socks, underwear (including jockstraps), shirts, pants and towels-all in rather gamy condition-were counted, gathered up in huge cloth bundles and then carried off to the Dhobi Ghat. A week later, it came back a little damp, but clean, pressed and folded, smelling of the wood smoke associated with the drying racks used especially in the rainy season. There was another odour, which we suspected was goat's urine bleach. "Dhobi itch" was a condition of the crotch and other parts of the torso that afflicted us from time to time. The standard treatment was a generous application of gentian violet, which left sufferers with spectacular purple privates, rather like tribal body paint.

Saturday also brought barbers, mochis (shoemakers), darzis (tailors) and boxwalas to the Hostel. The last were merchants selling an assortment of toilet articles and candy from trunks carried to the Hostel by porters. From them we bought Lifebouy soap, Palmolive shampoo, Kolynos toothpaste, Cherry Blossom and Kiwi shoe polish, Brylcreem for the hair, and other essentials.

Bakers and confectioners also put their offerings on display. It was an agonizing process deciding how to stretch one's meagre allowance over all of one's wants, making the choice between a tempting frosted pastry and a small Nestle's or Cadbury's chocolate bar. The latter came with a movie star's picture inside suitable for mounting in my "Stars of the Silver Screen" album!

The shoemakers and tailors were remarkable craftsmen whose skills we took for granted. With only a tracing of the outline of the right foot the mochis would make up a pair of chuppalis (sandals), regular shoes or basketball shoes to order. Three options in soles were available, rubber crepe, leather or leather with hobnails. These last were not popular with school authorities. They somehow didn't like the clatter and screech of hobnails on cement floors. Our mochis could also make lightweight spike track shoes. Similarly, the tailors, with our measurements in hand, would produce shirts, trousers, jackets and even two-and three-piece suits, if desired. These required more time and visits to their Landour shops for fittings and final assembly.

Saturday was the day we could walk to Landour and Mussoorie, only with permission, of course. There were movies to see at the Picture Palace, Rialto and Majestic. The show always started with newsreels and ended with the audience standing to "God Save the King." The Paris Restaurant was very popular, as were sweet shop delicacies, tea and pastries, and Vimto, a grape flavoured soft drink. The busy life of the bazaar was a kind of lively street theatre to be enjoyed on its own. On Saturdays, there were hillside picnics and invitations from friends who were living with their parents as day scholars. Class parties were also held on Saturdays.

Sunday was a serious day involving mandatory attendance at Sunday school and church, an afternoon letter-writing period when we were required to produce something in writing for our parents, and optional participation in a youth program, Christian Endeavour, or "C.E." This and church services were made more palatable by the presence of girls and the opportunity to socialize with them.

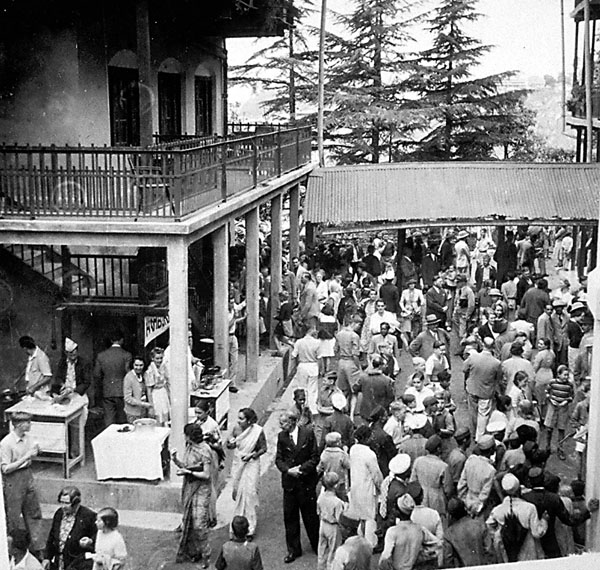

The school year at Woodstock ran from early March to the end of November. It was divided into two terms of three six-week grading periods each. In early June, the Woodstock Sale was held. It was a one-day fair and festival featuring, among other things, American candy, Baby Ruths and Cracker Jacks.

The Sale was followed by the Ten Day Holiday when hikes into the mountains or chaperoned holiday trips to places like Kashmir and the Himalayan resort of Sat Tal were organized. Mid-year exams and another holiday occurred late in July. By then the annual monsoon rains were upon us. They ended in September and the hillside community moved into the last two months of the school year with the autumn Four Day Holiday. There were field trips in September and October, the Biology, Sociology and Hardwar Trips and a trip to the Forestry Institute in Dehra Doon.

The Mussoorie Olympics were held in October. This was a track and field meet in which several of the other Mussoorie schools such as Bala Hissar, St. Georges, Oak Grove and St. Fidelis participated. Sports Day arrived in early November. It was held at Taylor's Flat near the Survey of India office in the Landour bazaar area. Class teams, organized into three divisions, Junior (Standards Three, Four and Five), Intermediate (Standards Six and Seven) and Senior (Standards Eight, Nine and Ten), competed against each other in boys' and girls' events. We wore custom-made track outfits in our class colours: Class of '41 colours were red and black\; '42 were blue and gold\; the Woodstock School colours were brown and gold. We marched in formation and massed into a giant "W" for the annual Sports Day photograph.

The last two weeks of November were filled with the stress and emotion of the year's end. Final exams, Baccalaureate Sunday, Graduation Day, The School Christmas, Prize-Giving, the Bonfire, the Farewell Dinner and, finally, Going-Down-Day!! (The exclamation points are in the Woodstock Handbook for 1942).

By late October air temperatures had begun to drop. Across the evening sky we could now see the "winterline," created by a cold weather dust layer over the plains. As the sun sank and disappeared it would leave behind a luminous sunset sky bordered by the top of the dust layer. Below the winterline, the shadowed air hung like an ominous opaque curtain, hiding the plains from view. That was the region we were about to enter!

It was a powerful symbolic experience for graduating seniors and others who were leaving India with their parents on furlough. Their physical ties with Woodstock and the Himalayas were being severed, possibly forever! The uncertainties and unknowns of a future life in the world below lay ahead. But the rest of us, with the sentimental words of Mr. Fleming's school song, "Homeward Bound" echoing in our hearts, headed off in our travel parties for the winter vacation, knowing we would be back in March and one rung higher on the school ladder. For us the immediate future was one of family, good food, vacation-friends and adventure on the plains.

Epilogue

Stan and Bev were married in 1947. After Stanley completed graduate work in sociology and religion, and Beverly finished her nursing degree, they moved with their two young daughters, Cynthia and Victoria, to Lahore, Pakistan in 1952. Stan taught English and History at Forman Christian College and Punjab University. Beverly worked at United Christian Hospital.

In 1963, Stan moved with his family to Berkeley, California where he earned his PhD in History at the University of California. He then joined the History faculty of the University of Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he taught until his retirement in 1990.

Stan, an avid photographer and traveller conducted several cultural tours to India in association with Air India. In 2004, he and his daughter Cynthia contributed articles to The Way We Were: Anglo-Indian Chronicles, (ed. Margaret Deefholts and Glenn Deefholts), a book on the global Anglo-Indian community experience.

The Union Church and house, the station, the residential areas and the market are still there, but the name Bengal Nagpur Railway has disappeared, replaced by the more prosaic South Eastern Railway. Contemporary Kharagpur's chief claim to fame is its elite Indian Institute of Technology.

Our seaside resort at Chandipur has been absorbed into a missile test range for the Indian navy. But the beautiful beach of our day is gone, destroyed by a Bay of Bengal cyclone in the early 1990s.

The wartime airfields (except for Chakulia and Kalaikunda), which half a century ago were busy with airmen and planes, are abandoned. The crumbled runways now mingle with the general historical detritus left by other exotic warriors who passed through India before them. The dead at Kalaikunda were transferred after the war, in accordance to the wishes of relatives, either home to the US or to the permanent American military cemetery at Carthage, Tunisia.

Now, having passed the sesquicentennial of its founding in 1854, Woodstock has transformed itself into a highly regarded international school better suited to the educational needs of its diverse students.

© Stanley E. Brush 2008

Comments

Add new comment