My Discovery of India -3

Category:

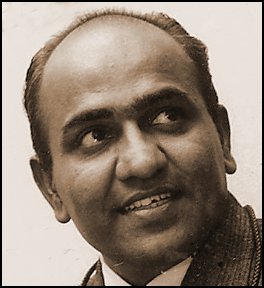

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

Editor's note: This story is reproduced, with permission, from Mr. Nagarajan's second not-for-sale book of his memories, Self-Portrait: The Story of My life, 2012. This website has several excerpts from his first not-for-sale book, A Pearl of Water on a Lotus Leaf &\; Other Memories, 2010.

This is the third of three sequential stories about his life after he left Mysore. Go to the first story in this sequence. Go to the second story in this sequence.

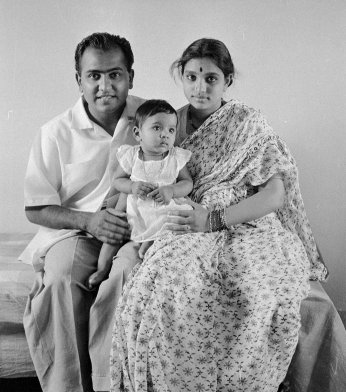

A Daughter

It was in Pondicherry my daughter Kalyani was born in the Hôpital de Government in 1959. A telegram arrived in Delhi informing me of the birth of a daughter to Meenakshi. An elated Mahalingam Iyer marked the arrival of his first granddaughter with much pomp and ceremony. I was not able to attend the function at Pondicherry. My wife returned to Delhi with the child after a few months. All seemed well until exactly on the day we were celebrating our second wedding anniversary in Delhi, another telegram arrived from Pondicherry bringing the devastating news that Mahalingam Iyer died of a cardiac arrest. I rushed to Pondicherry with my wife and child to take part in the rituals that followed. The home looked forlorn. I missed the venerable old man sitting outside on the thinnai.

Life returned to its routine. We enjoyed bringing up Kalyani. Meenakshi was an expert tailor. She had brought her Usha tailoring machine, a gift from her brother Ratnam for having passed the matriculation examination to Delhi. Kalyani wore new dresses for every occasion stitched by her mother. Meenakshi managed the home expertly. I gave her my salary packet (a modest sum) every month. She devised a simple method of budgeting for the month. She saved the money required in small envelopes titled "Rent", "Provisions", "Vegetables", "Milk", "Hand Loan" etc. so that she knew exactly the money left for other expenses. We had no room to splurge. The only luxury she allowed was to buy a bottle of Coca-Cola (priced 25 Paise) to be shared between Kalyani and me during the evening walk.

Kalyani was a bundle of joy. Every evening, she waited for me to return from the office so that she could enjoy a ride on my scooter around the park. I loved listening to her stories\; among them was a gripping account of how the next door girl was murdered by the young man who worked as a domestic help. A murder did take place next door and there was so much of talk about it. Her story was entirely based on hearsay. She would tell me the same story every evening with much wonder and excitement, but with added bits from her imagination.

Here's an unbelievable experience by me concerning Kalyani. She was around a year old. One night, I woke up suddenly from sleep, utterly shattered. I shook Meenakshi out of her sleep and told her about a terrifying dream I had. In the dream, I lifted the child and tried to make her stand on her legs. She was unable to do it\; and every time I tried, the child fell.

We looked at Kalyani anxiously. She was sleeping soundly. Meenakshi felt that there was nothing wrong with her and urged me to go back to sleep forgetting the bad dream. In the morning, it was my wife's turn to wake me up. I found her deeply disturbed. She told me that, despite repeated attempts, the child was really unable to stand on her legs. Kalyani was awake but still lying on the mattress. I lifted her up and tried to make her stand. She fell. We looked at each other helplessly and didn't know what to do.

Dr. A.K. Ghosh, our family doctor, would only open his clinic at 9 am. It was only seven in the morning. The two hours wait for the doctor was unbearable. We rushed to the clinic with the child and waited for the doctor. He arrived and found both of us devastated. He examined the child\; the problem remained. He advised us to wait till the evening\; and only, if the condition persisted, he would think on the next course of action. We were somewhat disappointed.

Kalyani appeared normal, smiling and active but refused to get up and sit. I was under stress and didn't go to office. By the evening, we noticed that Kalyani was trying to move her legs, and within a short time, she sat on the mattress. Both of us felt reassured that all may be well soon\; but we didn't have the courage to try to make her stand. We rushed to the clinic carrying the child. There was already a long queue of patients waiting to the see the doctor. Dr. Ghosh noticed us and called us in. He didn't ask us anything but took the child from her mother and talking to her sweetly tried to make her stand. A smiling Kalyani stood without any difficulty. The problem had disappeared. Dr. A.K. Ghosh had his clinic in a garage. He was very popular in the entire neighbourhood. He charged a mere Rs. 2 per consultation. We depended on him for all our health problems.

Magic Pills

I must mention here in some detail about a serious condition that I had developed over the years. It was a strange kind of allergy from which I suffered frequently. I tried many doctors including Dr. A.K. Ghosh. They gave me only temporary relief. The problem was this: Whenever I exposed myself to a cool and pleasant breeze, especially in summer months after a storm, I developed rashes all over the body resulting in unbearable scratching sensation\; sometimes even ending in incessant vomiting. This condition would last two or three days. Every time I had this attack, I had to be on leave till I got better. Mr. Kasi Nath, seeing my pitiable condition, suggested that I try homeopathic treatment under Dr. Roy, who belonged to the Ramakrishna Mission on Panchkuin Road.

One morning, when I had the allergic reaction, Meenakshi took me to the Mission. Dr. Roy, an old man, perhaps in his eighties, sat in front of a huge table at one end of a large hall. There was a heap of books on the table crying to be dusted. He was reading a book. There were no others in the hall. We stood silently in front of the table waiting for him to look up. Nothing happened for a while. Dr. Roy finally raised his head and gestured to me to sit on a stool next to his chair. He didn't ask us anything, but closely examined the rashes all over my body and asked me:

"What is the problem?"

I explained.

"Put out your tongue," he ordered rather gruffly.

I complied.

"Are you a vegetarian?"

"Yes," I said.

"I may ask you to become a non-vegetarian, if necessary."

I didn't say anything.

He finished examining me and wrote out a prescription. He told Meenakshi that the compounder would give her three bottles of pills marked A, B and C\; and that she should start giving me one dose of four pills, dissolved in a small quantity of boiled and cooled water, every hour, sequentially round the clock, for three days. He also wanted us to buy a bottle of Nicotinic acid tablets and take one tablet per day for three months. He asked us to see him after three days. We collected the medicines from the dispensing window. The medication was free. There was no consultation fee. Miraculously, barely after 12 hours of medication, the intensity of the rashes started reducing and the scratching sensation too became less virulent. I slept well. At the end of the third day, the rashes disappeared and I felt as though I had a rebirth. When we met Dr. Roy again, he was happy to see me well and smiling. The summer came and with it Delhi's Aandhi (dust storm) followed by a sharp shower, and a light gentle wind. I took out my scooter and went out for a ride with Meenakshi on the pillion. It was an exhilarating and an unforgettable experience. Till today, even after a gap of over four decades, the allergy has not returned.

Since this experience, my belief in Homeopathy has grown over the years. There are certain ailments which do not respond to allopathic treatment. The basic idea of Western medicine is to attack the problem or symptom directly. While this approach is effective in many ways, there are conditions in which the evil doer cannot be identified or something might prevent a direct intervention. It is also possible that no effective medication is available. In conditions like this, Western medicine becomes useless. Homeopathy or, for that matter, any Eastern medicine, adopts a totally different solution. Instead of attacking the problem directly, it makes the body stronger so that it can fight the evil better\; somewhat like making the economy robust in order to reduce crimes.

Bringing up Kalyani was a great experience. She grew up as a very naughty child, who sometimes, had to be tied to a chair to prevent her from going out through the main door and climb down the stairs on her own. We put her in a kindergarten named, very stylishly, "Casa de Bambini", which a Panjabi housewife was running, a block away. This arrangement gave Meenakshi some three hours in the morning free from Kalyani and her antics. When she was ready for school, we put her in St, Thomas' Convent, a well-known institution on Kali Bari Marg.

Second Daughter

Time rolled on. We wanted a second child, a companion to Kalyani. Vasanti was born at Meenakshi's brother Ratnam's home. Meenakshi delivered both the girls in the Hôpital de Government in Pondicherry: Kalyani in 1959 and Vasanti in 1962. We were given their birth certificates in French. Even though Pondicherry (now called Puducherry) had by then become a Union Territory, there were still some symbols of French administration, like the képi, a cap with a flat circular top and a visor worn by the Pondicherry police. Meenakshi's home was on "Rue de Chetty." The spoken language in many homes was French. A popular bakery sold French bread\; and one could buy choicest French perfumes from shops on Rue de Duplex, the main thoroughfare of the town. But so much has changed now. Sadly Pondicherry looks like any other big town in Tamil Nadu, full of kitsch.

We enjoyed bringing up the two girls. We never felt, at any time that we needed a son. Meenakshi became busier than ever attending to the requirements of both the girls in addition to running the house. It appeared that our life had reached a pleasant stage with the girls growing up. The home often echoed with their giggle and cries. Listening to them about their stories from the school became a habit with me every evening. I felt a sense of fulfilment and home became a happy place to return after the office.

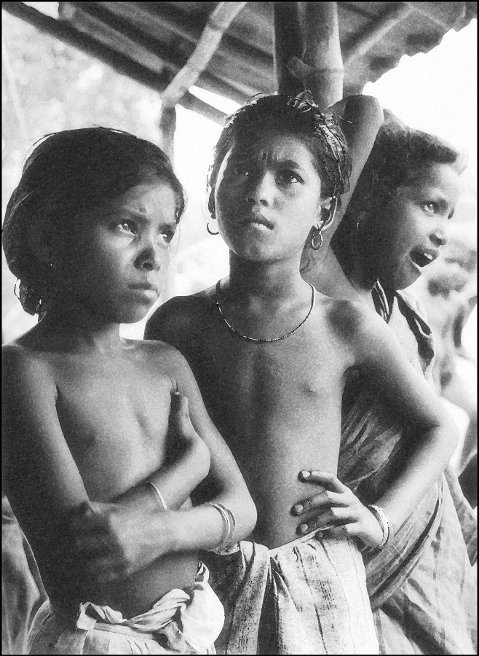

It was October. I was travelling in rural Bengal. Puja over, the air in the countryside had a special odour. The dust had settled. It was green everywhere. One late evening I got to a village in the 24-Paraganas with an unforgettable name of Dhop Dhopi. The villagers, dhoti-clad and bare-chested, sat in front of huts looking at the sky which was turning ominously black. Not far away, a knot of children was playing a game which I didn't understand. The dogs, security mongrels, were unaccountably silent. Stink of jute wafted from the ponds, but that didn't bother anyone.

Suddenly, clouds gathered from nowhere and it started pouring. To save myself and my cameras, I ran briskly towards a hut. The children ran ahead of me, shouting all the way. It rained and rained. The children, lean, bamboo lean with sunken cheeks, watched the downpour silently. There was wonder in their eyes. And what eyes! Grave eyes, dark eyes, eyes which are drips of monsoon rain. Ignoring the downpour, I looked at them, and their eyes. My hands worked involuntarily, picked up my camera and started clicking. The result: my best of children.

Back in Delhi, in 1966, I decided to hold my first one-man show of photographs with the Dhop Dhopi children and their magical eyes as the theme. I called the show "Young Eyes, Haunting". It was opened by Narayana Menon, who was then the Director General of All India Radio, at the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society gallery. The exhibition was a hit and received rave reviews.

Mexican Kiss

One evening at the exhibition, I noticed a visitor, a woman, short and slender, with remarkably delicate hands and feet, and dressed in a colourful skirt, ankle length, and a sleeveless blouse. She had meticulously applied her make-up and painted her fingernails, purple green. She was lovely without being beautiful\; her silky blond hair, unbraided, and of unusual length, flowed round her like a veil. She moved slowly looking keenly at every photograph on the wall. Meenakshi and I watched her with interest. She never turned towards us and continued moving slowly from one photograph to another. When she finished her round, she walked towards us like a dancer and sat on a stool in front of us.

Her name was Maria, from Mexico. She talked to us with much interest and showered unlimited praise on my work. She talked more about her travel in the country and less about herself. She stayed on with us in the gallery till the end of the evening and left along with us.

The following evening at the gallery I saw Maria again. She spent more time talking to me and was interested in knowing everything about myself. Though I liked her presence at the gallery, I felt something about her did not ring true. All that I could extract from her was that she would soon return to Nepal, and sometime later back to her country. She was not a painter, not a dancer, not a writer, not a singer. Then what was she? I found no answers.

The next evening, seeing her interest in us and our life, Meenakshi invited her for a South Indian meal the following day, a Sunday, at our home. Maria arrived promptly in an auto-rickshaw with a basket full of flowers and fruits. She ate a big meal and spent almost the entire day talking to us and our two daughters. After she left, my wife and I spent the rest of the day wondering about the mystery of our new-found friend.

One day I was alone at the gallery. It was closing time. Maria was still in the hall. She would leave for Kathmandu the following morning. Just before I left, Maria exploded a bomb! In a muted voice, she told me that she was in love with me and my work, and urged me to go with her abandoning everything - my family, my job and my photography!

And what followed floored me further. She pressed a soft kiss on my cheek. I found her face moist with tears. A sweet scent, which came partly from the European perfume and partly from her natural daintiness, wafted in little gusts on my face. I had not foreseen how great would be the ecstasy of being kissed by a woman who had kept her love for me within the fortress of her mind. All that I could do was to change the subject somewhat ungraciously. Barely a few moments later, she left the gallery without a word. I have not seen her since that unforgettable evening. Back home, I related the incident to Meenakshi. "I expected something like this. I am sure she is a spy, a butterfly. She has gone. Thank God!" she said with much relief.

If Maria was a spy, for whom was she spying? And, what does a spy get by cultivating me? Did I give her too much room to behave in the way she did? Or, was she just an innocent Mexican nymphet? Till today, I have not been able to get a convincing answer. In any case, I must confess, at some moments of introspection, I still think of her and wonder whether there could have been any other end to this episode.

I never had the experience of falling in love with anyone, although it was one of my unfulfilled desires. I married the girl I saw briefly from a distance, and fell in love with her beautiful eyes. I knew nothing more than this. Somehow, things worked out well\; the girl I saw and decided to marry, proved that she was the most precious gift I had ever received in my life.

Mridangam lessons

But I had some simpler but unfulfilled desires. I wanted to become a musician. I remember that when I was a boy of ten, going to school, I joined wedding processions to walk with the performing musicians. Later, while in Mysore, studying in High School, my interest shifted towards the percussion instrument, mridangam, the primary rhythmic accompaniment in a Carnatic music ensemble.

At home, I found no one serious about music. A music teacher came home in the evenings to teach Carnatic music to my elder sister. The parents were keen that she should learn to sing because it was difficult to marry off girls who couldn't sing. There was no question of a similar arrangement for me. They expected me to study seriously and score high marks, not waste time on avoidable pursuits.

One of the things I did after settling in Delhi with a job was to seriously search for a guru. I heard that a mridangam vidwan from Thanjavur had arrived in Delhi. He held evening classes for office-going persons like me. I got myself introduced to the guru, Mani Iyer, through a friend. Mani Iyer had learnt the art from none other than his celebrated namesake Palaghat Mani Iyer. It was difficult for me to attend his evening classes because, invariably, I returned from office late. I wanted someone who could come home and teach me early in the morning before I left for the office. Mani Iyer agreed to my request. He came home one morning to discuss the details. First, I needed to get two mridangams, one for him to teach and the other for me to play. Those sold in Delhi did not make the grade\; only those made in Madras were acceptable. I had to be ready after a bath before he arrived around half past six in the morning. It would be an hour's teaching every day.

It took some time for the two instruments to arrive. The first day went without much difficulty. The mridangams were worshiped in the Puja room in the presence of the guru, my wife and our two young daughters. The girls were terribly excited at the prospect of seeing their dad obediently sit in front of a teacher. The puja over, we sat on the carpet in the drawing room with the mridangams in front. I was told how to sit with the instrument. Next, I was asked to strike the instrument with my right hand, just once on its right side, to mark the beginning of the class at the auspicious hour. The instrument, tuned already by Mani Iyer, produced a high-pitched sound with a metallic timbre which thrilled me and the girls. The guru explained all the intricate features of the centuries-old instrument.

In the following classes, I was taught the four basic strokes (known as sollus in Tamil): Tha, Dhi, Thom, and Nam - strokes played with the fingers and palm of the hand. The guru repeated the beats in slow motion and stopped. It was my turn to play. When I progressed further, I was given slightly more complicated strokes sounding "Takkita, Takkita, Thakkita, Kita Tagu". I struggled to achieve that elusive coordination between the base of the palm and the fingers. After repeated attempts to get it right, all that usually happened was that my mridangam roared uncontrollably, breaking the quiet of the neighbourhood. It was at moments like this my wife would arrive thoughtfully with hot filter coffee in two cups and tumblers. To my guru and me, the aroma of Peabury (coffee) meant a welcome interlude.

Mani Iyer loved to chat with my wife especially about life in his home town Thiruppayalam, near Thanjavur, and the family he had left behind. He missed his wife and two children. It was impossible for a person like him to teach and make a living in his home town where very well-known gurus lived and taught. He had to come all the way to Delhi to live amidst Tamil families in Karol Bagh and try his luck. With me, Mani Iyer talked of other things: his celebrated guru, the early days at the Trichy All India Radio and about the unforgettable annual Thyagaraja Aaradhana festival at Thiruvayur, not far from his home town.

The classes continued, every alternate day, except for the two months during summer when my guru would travel south to his home town or when I had to go out of Delhi on official work. Then came a time when I fell sick. I was hospitalised. When I was discharged, I was advised rest for several weeks. All this meant long breaks from classes, which left me struggling to proceed beyond the rudiments of adi tala during my entire tutelage with the guru spread over two years.

Mani Iyer understood my predicament and never gave the impression that he had lost interest in me. When I was recouping from my sickness, he came home to sit with me, talk to me and make me comfortable. When I had to go to Mysore with my wife and children to visit my parents, he very graciously offered to go with me to the New Delhi Railway Station to book our tickets by train, one month in advance. Those days because of fewer trains plying between the North and the South, it was a big job to get tickets. One needed to go to the Railway Station the previous night, join the queue, sleep overnight on the floor, and get up early when the queue came to life in front of the booking window, which would open only at six in the morning. All the available sleeping berths on the train, which were not many, would get booked in a jiffy. One would miss getting reservation unless one was not sufficiently ahead in the queue. I hated doing this. Mani Iyer not only accompanied me to the booking office and stayed with me through the night and until I got my tickets at dawn. Even for a moment, he didn't think that a gesture like this was not called for from a guru towards his student.

After our holiday in Mysore, we arrived back in Delhi. I didn't find Mani Iyer. His room in Karol Bagh remained locked. I told myself that he might have gone to his home town, and so I waited until, one day, I got the devastating news that Mani Iyer had passed away in the room in which he lived all alone, due to severe diabetic complications. The families he was in touch with arranged his funeral and informed his family back home. More than a teacher of music, Mani Iyer was a simple and a great human being. He taught me all that mattered in a genuine human relationship. More than the art of playing the mridangam, he taught me the art of living.

Echoing Interior

Years later, during one of my tours of the South, I made it a point to call on his family in his home town. While his grieving wife made a cup of coffee for me, I clicked my camera to record the home of my guru. It was an unforgettable picture of a poor Brahmin musician's home. It was this picture that made me look seriously into the interiors of Indian homes for a possible sociological documentation. The project took over a decade to finish and became perhaps my best work with the camera as a photojournalist. I have devoted an exclusive chapter at the end of the book entitled "the Echoing Interior" to talk about this project (Editor's note: This chapter is not available on this website.)

The two girls grew up and went to St. Thomas' School on Kali Bari Marg in New Delhi. By the time they finished and left the school, Meenakshi and I had discovered two wonderful friends\; Joy Michael, who was the Principal of the school, and her husband Col. Hubert Michael. Joy piloted the school with great ability and made it one of the premier institutions in the Capital. Her two talented daughters Meriel and Kristene - became part of our family. Meriel qualified herself to join the Indian Audit and Accounts Service while Kristene went to Ahmedabad to study Design Pottery. Theatre was Joy's first love. She was one of the founding members of the Capital's famous theatre group Yatrik. Today at the ripe old age of eighty plus, she lives in Delhi with Kristene, who has established herself as a leading potter. Meriel is serving as Director of Excise and Customs. Christmas, every year, was the time for both the families to celebrate with much fervour and joy and Hubie's plum cake was a hit with all of us.

Kalyani finished her tenth and wanted to pursue an art course. She joined the National Institute of Design at Ahmedabad to do a five year diploma course in textile designing. Vasanti became a famous student of the convent and became the "Prime Minister" of the school cabinet. She was also somewhat disinclined to continue for getting a college degree. By this time much had happened in my official career which compelled me to quit the government. I shall dwell in detail about this in the following pages. (Editor's note: These pages are not available on this website.) Money was hard to come by with Kalyani at the NID, expenses were mounting. Vasanti joined Unicef in Delhi and gave us all the support we needed.

_______________________________________

© T.S. Nagarajan 2012

Comments

Add new comment