Memories of the 1950s

Category:

Reginald was born in Lahore before Partition. He writes books on various subjects pertaining to South Asia. A former London journalist, he now lives in Mid Wales with his actor wife Jamila. His latest book is Shaheed Bhagat Singh and the Forgotten Indian Martyrs, Abhinav Publications, New Delhi. A member of the Society of Authors, he is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

In the 1950s, India suffered as Nehru initiated his Socialist Five Year Plans on the Soviet model.

Food production declined as did industrial production. Nehru wanted to make India a modern secular state with nuclear power stations, vast dams, steel mills and fertilizer factories. He memorably declared: “These dams, steel mills and fertilizer factories are our new temples.”

The common man, however, bore the burden of what came to be known as the Licence Raj. I remember that nothing could be imported. Refrigerators were rare as were radio sets. Pakistan had TV stations and television sets. They had Cadillacs and Fords. India had no TV, and the rich had to make do with the Hindustan Ambassador, a Birla version of the outdated Morris Oxford. However, thanks to Nehru, India eventually became a major industrial power, able to stand up on its own two feet.

In 1949, I managed to clear the hurdle of the exacting Cambridge Senior School Certificate examination from St. Edward's, Milsington, Simla. I have to thank the Reverend Brother Browne who mentored my progress. My contemporaries were Kanwar Pal Singh Gill, the Top Cop, and the Ansari brothers, Khalid and Hamid. Hamid, formerly of the Indian Foreign Service, is now the Vice-President of India. At the same time in Bishop Cotton School was Ruskin Bond. He, like me, had decided to become a writer. Most of our classmates became senior bureaucrats, bosses in tea companies, generals, dashing fighter pilots, ambassadors, heads of corporations, or just gentlemen of leisure and pleasure. Ruskin and I would therefore be considered drop-outs.

I must confess that at the time Nehru's charisma had enchanted India. The man could do no wrong. Hence, many years later I wrote these lines:

Noble dreamer, Hamlet, poet at heart,

His charisma was immense\;

Though he lacked common sense\;

We believed in what he said:

Every word, every prevarication,

That sooner than we imagined

Misled the entire nation.

But at least he gave a vision,

A mission, an aim, a dream, a goal.

However, all that vanished long ago\;

We now lack decency of soul.

His misjudgements were colossal, his errors Himalayan.

And so died India's man of vision\;

Noble soul, gentle even,

But one who could not make a decision.

Nehru died disenchanted, shattered\;

His dreams dissipated, forever lost,

Never to see the light of day.

The irony is that by his bed

He'd scribbled lines by Robert Frost\;

Those echoing lines about the man

Who'd stopped by woods but could not stay.

(From my collected poems Lament of a Lost Hero and other poems)

The First Inter-University Youth Festival in 1954 was held at the Talkatora Gardens, New Delhi. It was the brainchild of Principal Sondhi of Lahore, the man who built the open-air theatre in that city before Partition. It was based on a Greek model. Sondhi, the first Indian principal of the prestigious Government College, Lahore was, in the early 1950s, an advisor to Education Minister Maulana Abul Kalam Azad. Sondhi proposed the idea of the youth festival and, Azad, who founded the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, was gripped by the idea.

The money was immediately sanctioned and acres of land were cleared to put up tents and kitchens for selected students from all over India. Special temporary theatres were erected for music, dance and drama. In those distant days, there was not such a plethora of universities in India. The senior most universities were Calcutta, Madras, Bombay, Banaras Hindu University, Aligarh Muslim University, Punjab, Delhi, Allahabad, Osmania, Baroda, Mysore and Agra. They were followed by other universities of varying qualities. At the time, there were no IITs or IIMs. JNU was not even on the horizon.

I had gone to Bombay to try my luck at journalism. Thanks to Frank Moraes, father of the poet Dom Moraes, I worked for FILMFARE, India's leading film magazine. Incidentally, Dom won the prestigious Hawthornden Prize for Poetry while he was an undergrad at Oxford. His second wife was the actress-model Leela Naidu (niece of the poet and freedom fighter Sarojini Naidu) and often called "one of the world's most beautiful women".) I also had the good fortune to be encouraged by the likes of Mulk Raj Anand, C.R. Mandy, Prem Bhatia and Khushwant Singh. It was then that I got to know the likes of Dilip Kumar, Nargis, Raj Kapoor, Sunil Dutt, Nutan, Madhubala and Meena Kumari.

All this was very heady stuff for a young man who was not even a graduate. But my father said: "You MUST get a degree!" And, hence, I reluctantly left Bombay, and went to Simla and joined a college there. I was two or three years older than my fellow students. They regarded me as their Guru.

Luckily, Simla had the Gaiety Theatre, established by the British. It is there that we students, under the guidance of Professor Sud, also from Lahore, staged plays. We were a dedicated group of budding actors, writers and directors. Prem Chopra (later, the 'villain' of many films) was one of us. Balraj Sahni came all the way from Bombay to judge our efforts.

Therefore, when the question came up: "Who will represent Punjab University at the First Inter-University Youth Festival in New Delhi?" it was quickly decided that Shaw's play You Never Can Tell would represent Punjab University. The stars were Vera Sundar Singh and me. (Vera, who was later known as Priya Rajvansh, was horribly murdered in Bombay. But that is another story.)

Nehru inaugurated the Festival.

I first saw Odissi at the Talkatora Gardens performed by Priyambada Mohanty, and that is what made me a devotee of Indian classical dance. She was a brilliant student of zoology but had learnt dance from leading gurus such as Singhari Shyam Sundar Kar, Kelucharan Mahapatra, Deba Prasad Das and Pankaj Charan Das. Though she became a Professor of Zoology at Utkal University, she continued to dance, and researched the history and technique of Odissi. Her daughter Ahalya Hejmadi also became a well-known Odissi performer.

At that time, few people had even heard of Odissi. Fortunately, the critic Dr Charles Fabri, a Hungarian who was a lover of all things Indian, in the audience was. He was enraptured, and started a crusade in the influential Statesman newspaper of New Delhi. He declared that Odissi must be recognized as one of the country's classical genres. It was then that India's dance establishment, many members of which were unhappy with Fabri 'poaching on their territory', were forced to take notice. It was not a case of a star being born but rather a whole new classical style being born or, more correctly, being discovered. I have recorded Priyambada Mohanty's historic Delhi debut in my book India's Dances: Their History, Technique and Repertoire (Abhinav, New Delhi).

Later, thanks to Fabri, the charismatic Indrani Rehman, already an established Bharata Natyam dancer, learnt Odissi from Guru Deba Prasad Das. She toured India and many foreign countries extensively. To quote Sunil Kothari, "Indrani, with her natural gifts, attractive stage presence and refined taste, contributed substantially to the fame and development of Odissi as a major dance form." Her daughter Sukanya also became an Odissi dancer. I got to know Indrani quite well. She possessed that rare quality termed 'class'.

It is worth noting that Indrani's mother, an American known as Ragini Devi, was herself an accomplished dancer. Even today, foreign-born dancers such as Sharon Lowen (American), Ramli Ibrahim (Malaysian) and Ileana Citaristi (Italian) have achieved high status as Odissi dancers.

The organisation of the First Inter-University Youth Festival was amazing. In groups, we students were allowed to sit and witness the debates in the Lok Sabha. I was there when Maulana Azad answered Opposition questions in chaste Urdu. He knew English well enough but refrained from using it since he did not wish to foul his mouth with a firanghi zubaan (language of the foreigners).

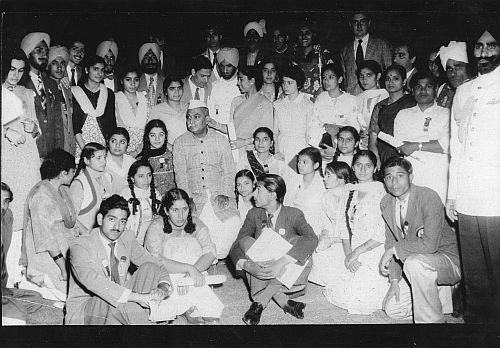

However, the greatest moment for us came when we were invited to Rashtrapati Bhavan to meet Dr Rajendra Prasad, ('Rajen Babu') who was the first President of the Republic.

President Rajendra Prasad, second row middle.

Reginald Massey, sitting cross-legged in front, looking back at the President

He was the man who told Nehru that he'd prefer to send his children and grandchildren to the local Municipal School rather than to the posh Doon School, known as the 'Eton of the East'. Why? Because the children of his staff (the cleaners, gardeners, washermen, etc.) had to send their children to Municipal Schools. And what was good enough for them was good enough for India's President.

India has few men like Rajen Babu today.

© Reginald Massey 2015

Comments

Add new comment