Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Sights, Smells and Sounds of Panipat

Category:

Tags:

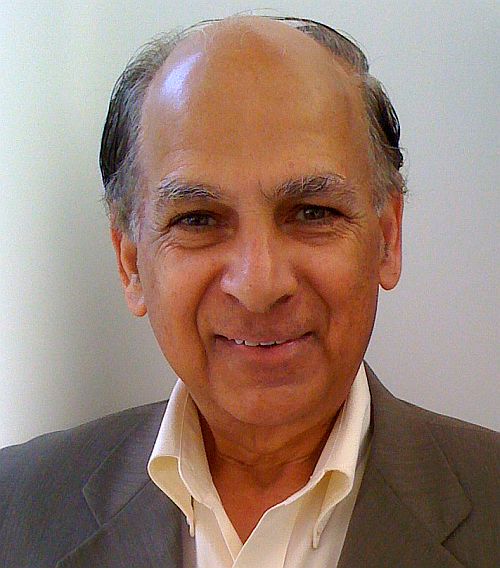

Dr. Juginder Luthra completed his MBBS from Medical College, Amritsar in 1966, and his MS in Ophthalmology from the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGI), Chandigarh in 1970. He moved to Nottingham, UK along with his wife, Dolly — a dentist from the Amritsar Dental College — and a daughter, Namita. They were blessed with twin daughters, Rohini and Rashmi, in May 1975. The family moved to Weirton, West Virginia in June 1975. Now their three loving daughters are married to wonderful sons-in-law, and Dolly and Juginder are blessed with six grandchildren.

I grew up surrounded by sights, smells, and sounds of Panipat from 1947 to 1959, when pursuit of higher education took me to Government College, Rupar, Punjab.

Partition and its aftermath

"Khuda ka vaasta tumhen. Aap ko apne bachchon ki kasam. (For God's sake. Swear upon your children). Please put your sword back. I have two wives and five small children to take care of," stuttered the man, wearing a round white cap, pleading for his life. His trembling body, the betrayed fear of imminent death in his eyes, the hands clinging to the feet of a man with three white lines painted across his forehead, begging for mercy.

Before bringing the sword down, which would create a limp body immersed in a pool of its own blood, the Hindu said, "Don't make me swear by my children. They were killed mercilessly by your Muslim brothers in Pakistan last week. Right in front of my own eyes! My wife tried to save them. The long sword simultaneously pierced through her and our only daughter, whom my wife was holding close to her chest. I was forced to witness this torture, tied to my cot. Their plan was to put the cot on fire at the end of the carnage, but an urgent call to kill another fleeing large family took the killers away. Besides, the striking strip of the match box had become wet with the spurted blood from the little neck of my last child. He was holding onto my helpless hands. The fifth son saved his own father's life! Should have been the other way. The guilt will kill me little by little every day, every moment. And don't worry about your two wives and five children\; we severed their heads from their sinful bodies in the other room five minutes ago. They are at peace and with your God."

Then all was quiet. The severed head, now cap less, jerked around for a while till it settled next to the quivering body soaked in its own blood. The men with three-lined foreheads and the bearded, turban wearing men, brandishing their blood tinged shiny swords, moved viciously onto the next target. They had vowed to take revenge for losing their wives, children, old parents and all the material possessions they had owned for generations.

We occasionally heard such stories from our parents and other elders, but read many more similar incidents much later in life. But, mostly, the dark shadows resulting from the partition of India were kept away from our innocent minds.

The sounds and sights of the hue and cry from the departing Muslims and the arriving, displaced Hindus and Sikhs in Panipat must have been experienced by me, a three year old boy in 1947. The screams of the victims, the insane fury of the perpetrators and sights of mangled bodies on the trains coming from and going to the newly formed Pakistan must be buried deep in my grey matter. All these horrific events transpired following the division of India and creation of the new country, Pakistan, on August 14, 1947.

Like a river, life has the tenacity and need to keep flowing regardless of the current or preceding turbulent obstacles, small or large. Survival mode kicks in, time for regrets and counting the losses is placed on the back burner. As children, we did not fathom the mammoth obstacles and turbulences our elders were going through, enduring their effects and myriad ways of surmounting them. We were busy enjoying our childhood. Surely, our parents dealt with numerous problems, but they kept the younger ones completely insulated from the trauma.

"Suraj and Prem, you guard the house from 6 AM to 4 PM. Virinder, you watch the gate from 4 to 7. I will stay up all night," Kundan Lal, our father, known as Pitaji, ordered his three elder sons. They were the oldest of the six sons.

Two sisters needed full time protection as well. One day, there was a scare in the household as Kanchan, the younger sister, wandered off without telling anybody. Unaware that the whole family was frantically searching for her, with fears of every horrific possibility in their minds, she was merrily playing with some friends. Such was the frightful environment in the early days after the partition. All the elders had their hands full immediately after the family's sudden, rushed arrival in Panipat when we left Khanewal which had now become part of Pakistan.

Pitaji's paternal uncle, Dr. Gopi Chand, who, with his family, was passing through Panipat on his way to the safety of Delhi, had earlier sent an urgent message to Pitaji: "I have taken possession of and am holding an abandoned house, vacated by a Muslim family fleeing to Pakistan. It will be perfect for your large family. Come as quickly as possible before someone else pushes us out."

In May 1947, our whole family, including my mother, pregnant for the tenth and the last time, had left our permanent home in Khanewal, district Multan (in current Pakistan) to our summer home in Sabathu, a cantonment town near Shimla, for the three months of summer vacation. The family comprised of my parents, seven siblings, including the one who was yet to be born in August, 1947, and Lalaji, my paternal grandfather. (My maternal grandparents had stayed back in Sargodha, Punjab, and migrated after the partition.) Two older siblings had died around age 6 years due to smallpox several years ago. Our family's plan was to return to our permanent home in September, 1947.

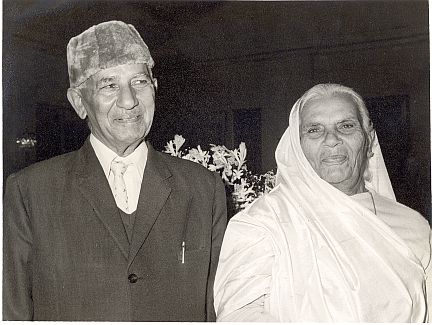

Kundan Lal (left) and Vidyawati Luthra, the author's parents. About 1970.

L to R: Madhu Khera (cousin), Juginder, Krishan (brother) Behind Virinder (brother). About 1952.

L to R: Ashok (brother), Juginder, Krishan (brother). About 1954.

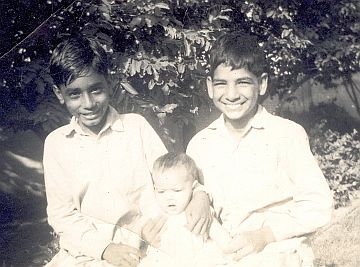

L to R: Anil Narang (Cousin), Nishi (Niece), Juginder. About 1956.

All types of information was circulating about the possible and impending partition of the country. No one knew for sure when or if it would really happen. But then, without much warning, Partition was suddenly announced in June, 1947. On July 8, 1947 Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a British barrister arrived in India. In the next five weeks he drew a line on the map of India with ink. This black line on the map turned red in real life with the most massive bloodshed. The history of the region and its people changed instantly. Our family abandoned our land, home, and almost all material possessions, but was safe, together, except for Nanaji and Naniji, my maternal grandparents, who were still in Sargodha and wishing for an undivided India.

Pitaji immediately led our family from Sabathu to this abandoned house, deep in the city of Panipat in the fall season of 1947. It must have been vacated in a rush because some pots, filled with partially burnt vegetables, were still sitting over the cold ashes of wood burning chulhas. We called it our first permanent home in the Independent India. It had to be guarded around the clock.

In 1950, we moved to the new development called Model Town in house number 2. This became the permanent home to live and die in for Kundan Lal and Vidyawati Luthra, my father and mother. This was the safe haven where they happily struggled to raise a large family in Panipat.

Once the fires of partition had cooled down and extinguished, the three communities - Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims - lived in harmony, peace and non-judgmental acceptance. Every religious sect or group and individual followed their respective religious practices without questions or fights over "My religion is better than yours." Survival was the common mantra.

Growing up in Panipat

The sights, sounds and smells of Panipat in the 1950s and early 60s are recorded in a recollect-able manner in my memory bank. Activities of a busy household occupied by twelve persons, ranging in the ages from 3 to 80 years, surrounded the young senses and mind. The home was filled by sounds of laughter and crying\; scents of food, rain, flowers, and odours of open latrines\; and constant flurry of activities beginning before the sunrise and ending past the sunset. This package was delivered to us in an envelope of security and much love.

The city woke up with the hazy sun filtering through dust and smoke from the burning coal and wood, and cool fog. Crowing of the roosters and chirping of the birds in the abundant trees were our wake up calls.

Mornings were also announced by prayers and hymns being sung over loud speakers. The newly arrived Hindu and Sikh refugees from what was now Pakistan had brought their religious practices with them. Many brave Muslims stayed back in the old city. No Muslims resided in the newly developed Model Town. Members of each sect started their days with competing sounds of Allah U Akbar, Gurbani, chants of Hare Rama, Hare Krishna or recitation of Hanuman Chalisa to invoke the god Hanuman. Hindus and Sikhs set up Temples and Gurudwaras in the newly constructed houses. There were still several old mosques present in the old city.

Our family's place for prayers, Shri Ram Sharnam, did not participate in this morning ritual. Swami Satya Nand Ji, our first Guru in Panipat, taught us that Ram is the sound of the unseen God. Small gatherings started at the home of his disciple, Shakuntala Behanji, our next Guru, in house number 76, then number 9, both of which became too small for the escalating large gatherings of devotees. Shri Ram Sharnam was inaugurated by Swami Ji on October 9, 1960 at 588 Model Town, which has been growing ever since, first with Shakuntala Ma, and now under Guru Darshi Ma. Melodious Bhajans, Amrit Vaani, Sarv Shakti Mate Parmaatmnein Shri Rama E Nama and discourses were recited over a low volume speaker system during the evening's prayer sessions.

Roosters crowed, dogs barked, crows croaked, men and women with water filled lotas (metal pots) in their hands made their way to the open fields. Some people were seen taking baths in cold water, shivering, and chanting Wahe Guru, or Ram, or Om Namo Shivaaye. Shopkeepers started raising shutters of their shops. Tea stalls began preparing hot coal for making much needed morning tea. Smoke rose to fill the air with its acrid smell and grey haze. Vegetable sellers were busy filling their stalls with several fresh vegetables just arrived from the Sabzi Mandi. Chewing their daatan (Neem or Keekar tree twig used as toothbrush), spitting as they went along the streets, cloth bags in hand, men and women were making their way to the market to buy the supplies for the day. Milk vendors, newspaper sellers peddled around on bicycles. Children, in their respective school uniforms, started walking to their schools, some playfully happy and some still yawning, missing their cosy beds. The whole town was waking up. Panipat was coming alive.

A large body of stagnant water, called talaab, west of the railway line produced an odour, which spread out beyond its borders. It also provided a fertile home for the mosquitos to hatch, multiply and spread malaria.

The washermen (Dhobi) and women washed clothes at the edges of this body of water. The dust filled wet clothes, soaked in soap overnight on low heat, were beaten by wooden flat bats or swung hard onto flat rocks. They were rinsed in the water and squeezed by twisting over and over till they looked like braids. Multicoloured rows of clothes were hung on clothes lines or laid out on the adjoining land along the talaab to dry in the ever present sun. Soap filled water flowed back into the Talaab.

Dogs, half submerged cows and buffaloes bathed, urinated in and drank the same water. This is where people and cattle took baths together. People filled their lota with water for washing after defecating in the open fields along the railway lines\; many did not have outhouses or latrines yet.

My Mataji, as my siblings and I called our mother, and Ganga Devi, a regular hired help, used to wash the clothes at home in a similar manner, except the water was from the city water pipes or hand drawn pumps. They used a bat, about three inches wide, with a round handle to beat the dirt out of the clothes. A single steel wire, stretched across the whole yard, was used to hang the clothes. They used locally made pale coloured, square shaped bar of desi soap for the sole purpose of washing clothes. It was too harsh for the skin during bathing. We used commercially made, red Lifebuoy soap for bathing. Brown, translucent Pearce soap was too expensive.

A newly established Sugar Mill was located at the southern tip of Panipat. It was notorious for announcing the approaching Panipat to the people traveling on the Grand Trunk Road, commonly called GT Road, and in the trains. The characteristic pungent odour greeted the visitors, making them cover their noses till they went past the city or got accustomed to it. Residents were surrounded by it, breathed it all the time, and no longer noticed it. They were thankful for the much needed jobs provided by the Mill to the thousands of refugees. What was pungent to the outsiders was a sweet smell of livelihood and life to the residents.

Naaliyan, open sewer drains, lined between the homes and paved streets, carried a slowly moving black sledge of solid waste from kitchens, bathrooms and partly from the latrines. Bulk of the excreta would be picked up by jamadars (male sweepers) or jamadarnis (female sweepers) in a metal container. Covered with dirt or coal ash, it was disposed in the dumps on the outskirts of the town. The sludge in the naaliyan was prodded along by the scant water and it was not uncommon for them to get blocked. The homeowners would use water in baaltiyaan (buckets) to move the smelly stuff beyond the boundary of their own house. Private or City employed jamadars used a U shaped metal piece, connected to one end of a wooden shaft, to pull out the black sledge blocking the open drains, onto their shoulders. The foul smell and sights of these intermittent dark piles surrounded by flies were perceived as normal by us.

In those days of relative poverty, I remember once throwing a one Rupee coin in this sludge filled naali. The whole family spent, in vain, half a day searching for the lost treasure with scoops and bare hands. Most likely, that day we ate roti with salt, onions and achaar - no vegetables or daal. And surely I got a thappadh or a smack with a broom from Mataji.

The sewage system was meant to carry off the rain water as well. It was obviously insufficient for the job, as was evident after every rainfall. The shallow playground would get filled and turned into a swimming pool for the squeaking children and heat exhausted animals.

Pitaji had planted various fruit bearing plants and a variety of perennial flowering bushes. Raat Ki Raani, (queen of the night) opened its thin, elongated white flowers, spreading its unique scent all over our 1,200 square yard lot. It also permeated into the house. It was said that the smell attracted snakes\; children approached the plant carefully watching for any slithering movements. During the days, white Jasmine flowers, orange and yellow marigolds, purple Bougainville provided colour and fragrance. Mango tree formed clusters of pale flowers, called boor. Anarkali, the flower of yet to be born pomegranate, was one of the prettiest flowers in our yard. Covering the centre of the wall, between the two grey painted entrance metal doors, was a pinkish white flower bearing climber plant. Flowers from okra, eggplants, large yellow ones on the Thori vines, guavas plants and others mentioned above invited honey bees and bumble bees for cross pollination. Butterflies of different colours and sizes hopped from one flower to the other.

Once the fruits started forming, a large number of green and multi-coloured, chirping parrots provided constant beauty and nuisance. They would take a bite on the raw guavas, not like it and damage the fruit. Our job was to shoo them away with gulel or beating of drums. Crowing of crows, looking for unattended or discarded food, used to be connected with superstition of arrival of unannounced guests. Their coarse sounds were contrasted by the sweet sounds of koyals. Anyone who sang a melodious song was complimented "Bilkul Koyal jaisi awaaz hai"(Sound is just like that of a koyal).

Buzzing sound of the abundant houseflies during the day and mosquitoes at night filled the air during summer time. Flies were ignored or just swiped by hand or hand held fans. There were too many to kill. Flit was sprayed into every room in the evening and the doors were closed for a while. After that, we entered the rooms carefully closing the doors quickly before the next platoon of mosquitoes could follow. Darting tongues of the crawling lizards, magically holding onto the walls and ceiling, took care of any remaining insects. We looked at them as friendly chipkali, but they spooked our children during our annual visits during the 1980s and beyond.

Groups of stray dogs barked and roamed the streets. No one had a pet dog or cat. People would throw a piece of roti or stripped and marrow sucked bones to them. They became nuisance during the night and early hours of the mornings, when they would engage in loud barking fights over the prized leftover, unattended or discarded bread or bones. Loud barking ended with some dogs whimpering, declaring the winners and losers. Losers generally tucked their tails and meekly walked away. The term Dum daba ke bhagna came from such scenes.

Our home was about half a mile west of the busy train station and the tracks, called railway lines. Another half mile further east was the main national highway, GT Road. Clustered along and east of the GT road lay the old city. The High Schools were built along this road. There were three - Sanatan Dharm, Arya, and Jain High Schools. Everyone living in the Model Town had to cross the railway lines and GT Road to get to the schools, bus stand, public offices and markets.

There was only one overhead bridge on Assandh road, built after the partition to facilitate access to Model Town. It was used by pedestrians, bicycle riders, bullock carts, trucks, tractors, occasional cars and buses. There was a small underpass south of it, which was used by pedestrians, bicycles and rickshaws, mostly when the railway phatak (crossing gate) was closed. Phatak closed before the arrival or departure of the trains. A variety of vehicles created long lines on the steep road on both sides of the crossing. Pedestrians and bicyclists would squeeze through and keep crossing the lines till there was just no chance of escape from the whistling and rushing trains. Some were not so lucky.

Most of us did not go over or under the safe passages across the railway lines because of the distance from home. We simply looked both ways and walked across the open railway lines or at times in between the dubbas of stationary goods trains, hoping that they did not start moving while we were still under them. There were only four train tracks at that time.

Panipat Junction was on the main route connecting Delhi and rest of India with the north and northwestern parts. The railway engines would scream loud whistles at all hours, mainly to announce arrival and departure of the trains. The main reason was to prevent accidental crushing of people who would continue their hops across the railway lines even in the face of oncoming trains, betting their lives that their legs would win the race against the lunging train.

Endless blaring of the horns from the ever increasing number of cars, buses and trucks was a normal phenomenon on the GT Road. Ringing of the bells by bicyclists and rickshaw pullers added to the noise. "BauJi, hut ke" (Sir, please move), rickshaw pullers and tonga drivers would say to the constant stream of pedestrians competing for the space on the roads.

Model Town was quiet\; hardly anyone could afford a car. Sugarcane loaded trucks and containers pulled by tractors, followed by the children running and pulling out the sugar canes, drove on our roads.

"Bol Jamooore, peeche lambe baalon vaale sahib ki pocket mein kya hai, chashme vaale sahib ke hat ka rung kya hai?" The man in the middle of the encircling crowd would ask the sheet covered boy, jamoora, lying on the ground. In a high pitch, the boy under the cover of the sheet, to the amazement of the crowd, would accurately describe a pen, a comb and the colour of the hat. He would even describe what another person was planning to do that day, another's future. The impressed crowd was willing to pay a chavanni (four Anna coin) or duanni (two Anna coin) to the man for asking the jamoora their future or a solution to their problems. Little did we know that the persons described in the audience were planted and were part of the team.

Fortune tellers with a bird in the cage, pulling out fortune card for people paying a fee, were commonly seen along GT Road.

Proponents of Shilajit attracted another set of crowd standing in a circle. Some were touting powders, pills and potions to cure bawaseer (haemorrhoids), upset stomach, Kala motia (glaucoma), safed motia, (cataract), infertility, curing all dental problems and everything else in between. Such fake doctors tried to sell their cure for all diseases in the trains as well. It was not uncommon to see lay persons sit on the roadside pulling rotted teeth with pliers. Bill boards and painted signs covered every visible wall along the GT Road showing names of Hakims and RMPs - Registered Medical Practitioners. Bawaseer and infertility were the most common issues. A big man, with a big moustache, a Hakim appeared on many walls.

Trained monkeys and bears performed tricks to amuse the crowd, who would throw coins into a tin container. We used to love it when a stick-holding male monkey would "marry" a sari clad female monkey, and lead her away, apparently to his home.

Another crowd of people surrounded a couple of men, one playing the been, while the other uncovering jute baskets. A cobra crawled out, its head standing at right angle to the body, black beady eyes followed the movements of the been, and at times darted forward, its tongue sticking out to strike the been player. We used to get squeaky scared, very nervous and worried for the player. Later we learnt that the venom sacs had been removed, and any snake bites, if they happened, would be harmless. Pythons crawled out of bigger containers and wrapped around the bodies of the performers. Some bold spectators were also given the chance for this feat. For a fee.

There were many signs on the walls, some with the pictures of donkeys, saying - Dekhiye, gadha peshab kar raha hai, (Look, a donkey is urinating). This did not prevent men, their legs spread apart for the stream to flow through without wetting their feet, from standing there and urinating. The smell of urine permeated the air so much that we were accustomed to it. It went un-noticed till we reached the signs on the walls, where the sight of spread out legs brought the smell into our conscious mind. At the end of the act, some men vigorously emptied out the last drop.

GT Road was known for overturned trucks, hit and run accidents, and unattended victims on or along its sides. If one saw a victim, it was considered best to ignore it, and not report it to the police. The fear was that whoever would report the accident, the police held him as the prime suspect unless proven otherwise. Ambulances did not exist. Those who made it to the government hospitals received no or delayed treatment as they had become police cases. An FIR (First Incident Report) had to be filed before any examination or treatment could be initiated. Many victims did not survive the wait. There were no medical malpractice lawsuits ever filed. In fact, we heard that term when we came abroad in the 1970s.

The roads in Model Town were wide and crowd free. Going through the galiyaan of the shehar old city) was another story. The narrow streets were crowded, life in motion: People rubbing shoulders, splashing red fluid, like a pichkari, from their mouth indiscriminately on either side, while chewing the Paan\; bicycles and rickshaws weaving their way through the swarms of moving or gossiping stationary bodies\; people haggling loudly with the shopkeepers of various shops that lined the streets.

During the summer season, most people wore white cotton clothes, dotted by black burka covered Muslim women, whose number kept increasing as we went deeper into the old city. Their number would significantly rise as we approached the famous Kalandar Chowk, the site of Kalandar's Masjid. Here the population was almost entirely Muslim, and it was here that we had taken our first home in Panipat in 1947.

Election times brought out rickshaws and tempos, with large posters attached on the three sides showing names and symbols of the party. Portable loud speakers blared loudly, urging people to vote for their respective parties. Many people were illiterate. At the time of casting their votes, they pressed their thumb on an ink pad and imprinted it on the ballot paper.

One party always chose the symbol of a hand, to become easily recognizable. There were many national and local parties with their individual insignias. Most popular was the Congress Party. Their leaders would wear white, boat shaped caps. Their sign was GandhiJi's Spinning Wheel, Charkha. These symbols were meant to cash in on the recently won freedom from the British Raj of almost 200 years.

The rickshaws were also used to have large boards depicting the currently playing movies in the two cinema halls we had along the GT Road. Large posters of these movies were also pasted on the prominently visible walls and free standing display bill boards.

Going to the cinema halls was a major event, although rare due to financial constraints. Tickets used to cost 4 to 8 Annas (1 Rupee = 16 Annas). There used to be three show times: 3 to 6 PM, 6 to 9 pm, and 9 pm to 12 midnight. Every few months, we would go to the 6-9 pm shows. The hall used to be packed. Sometimes tickets were sold in black market. Advanced tickets were not sold. They were purchased from a partially closed window where a hand could be inserted through a space at the bottom of the metal guards. Money was exchanged for a paper ticket. Some people would buy tickets in bulk. Before long, the window was shut, a sign board depicting House Full was placed next to it. The line was still long and people were eager to see the Film. The bulk ticket purchaser then, in hushed voice, went around and tried to sell the ticket by saying "dus ka ek, dus ka ek or bees ka ek (one ticket for 10 or 20 Annnas) depending on the demand.

It was an illegal act. But the cinema owners, black marketers and even the policemen, with their danda, were part of the scheme.

Movies used to be about 3 hours long with an interval. Vendors came into the hall, selling tea or Moongphali (roasted peanuts in the shells). Some people went out for the urinals, or tea and cigarette stalls. Smoking was allowed inside the hall but not during the showing of the film. The National Anthem was played at the beginning. Everyone used to stand and be perfectly still and silent. We were relishing our Freedom from the British. At the end of the show, however, the floor would be covered with shells of moongphali.

Dev Anand was our family's idol and hero. His puffed hair style and raised collars at the back were copied by the boys. At times, even after being told not to go to see the film, we went ahead anyway. Once, I stole 6 Annas from the space under Mataji's Singer sewing machine to see Jagriti. Invariably we got caught and got reprimanded by Pitaji.

The early morning music from Vividh Bharati still resonates with fond memories. Listening to the running commentary of the five-day Cricket test matches brought life to a standstill. A commonly used sentence during these days was "Bau Ji, score kee ho gya hai?" (Sir, what is the score?). The radios and transistors were switched on at homes, offices and shops. We listened to it on the fixed radio, and later, in 1957, on a portable light brown leather covered Transistor brought by our brother, Prem.

The whole family listened to Binaca Geet Mala on Wednesdays from 8 to 9 PM on our black Murphy Radio. Games were finished, food was consumed before 8 pm, and no other activity was scheduled between 8 and 9. The voice of Amin Sayani is ingrained in our minds. The show was broadcast from Radio Ceylon. Bhaaiyo aur Behano, aaj ka dasveen padaan ka geet hai....and finally, with a celebratory music, Pehli padaan (the top hit song) was announced. Such sounds filled the air in the usually noisy but now quiet household at 2 Model Town, Panipat.

______________________________________

© Juginder Luthra 2015

Editor's note: I approve all comments written by people. The purpose of approval is to prevent unwanted comments, inserted by bots, which are really advertisments for their products.

Comments

Add new comment