Latest Contributions

Saklibai and her Family

Category:

Jitendra (Jeet) Sanghvi is a Registered Professional Engineer. He is the Structural Engineering SME and Senior Civil/Structural Engineer for the real estate division of a multinational automotive manufacturer. Jeet resides in Metropolitan Detroit. Jeet is also a fitness and healthy food enthusiast, and enjoys reading and travelling. He is a member of the Jain Society of Greater Detroit, where he teaches Jainism basics to Middle School children at the temple on Sundays.

Saklibai, my Dadi or Grandmother, was born around 1890 as an only child in the small princely state of Sirohi, now part of Rajasthan.

At this time, many in her Jain community were looking for new opportunities outside the small fiefdoms under the British Raj. Pune (erstwhile Poona), Ahmedabad, and Mumbai (erstwhile Bombay) had a lot more opportunities, unlike the hundreds of princely states in the Indian subcontinent. Travel to distance places was becoming increasingly feasible and relatively faster than before due to the railway system introduced by the British.

Saklibai's family arranged her marriage to my Grandfather, Manikchand, the soft-spoken younger son of Vanaji. Vanaji, an Entrepreneur and the founder of the Vanaji Rajaji Pedhi, a banking and money lending centre, was becoming financially successful in the Poona Cantonment area. Vanaji had a younger brother (who later died childless), an older son, Lumbaji (my Grand Uncle) and three daughters, one of whom - Sadibai (my Grandaunt, who was called Sadi Bhua by my Dad and all of us) outlived all her siblings to a ripe old age of ninety. She was alive, along with my Dadi Saklibai, during my teenage years. Vanaji was a widower himself, having chosen not to remarry.

Saklibai's role in her future married life was going to grow bigger than a traditional housewife's usually would be, vis-à-vis taking care of her family which would include her husband, young children and, as was customary in the joint family system - her in-laws.

Until almost the late 1940s, most of the women in the family still stayed in the ancestral home in Sanpur, near Sirohi. The men conducted their business in faraway Poona, a two day journey by train, and then camel carriage from Abu Road or Sirohi to Sanpur. They frequently visited their safe haven and familiar grounds in present day Rajasthan. This would change in future, as newer homes and properties were purchased.

Indeed, these ancestral areas were familiar grounds. I was retelling my daughter, during a trip to Mount Abu, a story that sounded unbelievable even to me then. My aunt (Bhua) Dharmibai, and several of her cousins (Lumbaji's children), led by an older male cousin trekked all the way down from the Delwara Jain temples on Mount Abu to their home in Sanpur. Of course, as my Aunt fondly recollected, several of her cousins were screaming at their older brother, because this was a journey of several hours, it had gotten dark by the time they reached home, and it was without the help of modern day gear and brand name shoes!

So Saklibai entered my Great Grandfather's household as the younger daughter-in-law. The Sanpur home already had an older daughter-in-law, the wife of Lumbaji. Prior to Saklibai's wedding, the older daughter-in-law had already borne a daughter. As Vanaji's wife had passed away, they did not have a mother-in-law. They got along reasonably well, and managed the household together.

In due course, my Baasa (my father's older brother, Baasa means older Uncle in many Rajasthani dialects) Punamchand was born to my grandparents. This was a cause for celebration in the household since he was the first male grandchild of Vanaji, and hence a future heir. During those times, medical practice was limited to the local Vaidya (Ayurvedic doctor), and midwives helped in childbirth. Infant mortality was high. My Dadi and her sister-in-law both lost children during childbirth and during some of their pregnancies.

In due course, both women gave birth to other children. My Grandaunt had a son who was a couple of years younger than my Baasa, and a year older than my Bhua Dharmibai. Thus the joint family kept growing, though Saklibai lost three children in the next several years. Her sister-in-law had three more daughters during this time.

By the 1920s, Saklibai had a fifteen year old son, Punamchand, who was already married and a daughter, Dharmibai, who was engaged. In the meanwhile, Punamchand and his cousin, in the tradition of other men in the family, had started living in Pune and getting high school education, while the women were mostly all in Sanpur.

Sakilbai's last pregnancy occurred a few years after Punamchand's wedding. This pregnancy was a pleasant surprise for Saklibai, since she had lost almost all hope of having any more children. She gave birth to a healthy baby in the form of my father, Ratanchand. A couple of years earlier, my Grand aunt had her final pregnancy too, and gave birth to her last child. Unfortunately, she died in childbirth, and the little baby boy died in a short while too.

Vanaji Sanghvi's Partial Family Tree

The family dynamics changed from now on. After my Grandaunt's passing away, the widowed Lumbaji chose not to remarry. This meant, that collectively, Saklibai was now going to manage the household with five girls (four nieces and one daughter) and three boys (one nephew and two sons), although the older niece been married by now, as was Punamchand.

This was an important and challenging task in absence of adult men, who were mostly in Poona. As the surrogate mother, Saklibai was responsible for organizing the wedding arrangements for her nephew and nieces, along with her own children. Except for my father, who was much younger, she did accomplish all these responsibilities soon. Her nephew and nieces looked up to her for advice and respected her, as they would their own late mother.

Things were changing in Poona too, where Vanaji and his sons had established a successful business.Vanaji had also started attending discourses at the local Jain centre by the Jain Acharya visiting the Pune camp area. Vanaji was inspired by these sermons. He started aspiring to organizing a Sangh. This was to be no ordinary Sangh, because the itinerary he had in mind was elaborate and ambitious. The destination was far-away Shikharji, the holiest pilgrimage centre for Jains, inclusive of all sects. It is believed to be the location where twenty of the twenty-four Jinas or Tirthankars in the last time cycle attained Nirvana

Traditionally, Sanghs were huge undertakings. They were conducted by the sponsors to improve their eternal future. Jains believe in the cycle of Life and Death. Performing a major task like a Sangh, in helping others perform a religious pilgrimage, would alleviate multiple cycles of birth and death in the future and expedite the aspirant's attainment of Nirvana or Salvation. The Sangh was always based on the financial resources of the host\; it also gave the sponsor and their family a higher social status in their society.

Until then, Sanghs were mostly "Walking Sanghs", originating from the organizer's home town and culminating in the Jain Tirth (pilgrimage centre) of choice. The participants would walk a couple of hundred miles in 30-45 days, with daily sleeping and food arrangements for the participants at places on the way. Although a Sangh always had "open seats", the number of people who could participate in the Sangh was based on the organizer's budget and discretion. Usually, the number of participants ranged from few hundred to a thousand.

By the 1920s, India's railway network had expanded to cover much of India. Vanaji decided to use this extensive network for the Sangh. The planning for the Sangh started in 1928, when my dad was about one year old. Vanaji wanted the Sangh to start from Shivganj/Erinpura Road (present day Jawaibandh) railway station, near his ancestral home in Sanpur, and travel via Agra, Mathura, Kolkata (erstwhile Calcutta) and to Parasnath Hill. The return would be via a similar route, passing through what is now Bangladesh.

Erinpura Road was a cantonment for the British soldiers at the time, and hence had been connected to the rail network. Many of the stops planned for the Sangh were in locations of Jain historical significance, and local organizations were enthusiastic and welcoming to host the breakfast and lunch. However, food could only be arranged if the local centre was located on the planned railway route. Of course, no night meals were organized, since in the Jain belief system, eating after dark causes undue damage to living organisms, and is generally considered unhealthy. An important decision was made to allow cooking at Railway stations, if required.

The Sangh needed to have a married couple as the Lead Sponsor. This was a traditional aspect of the organization process. Vanaji and Lumbaji could not do this, as they were widowers, having chosen not to remarry. Since my Grandparents were the next in the line, they became the formal sponsors of the Sangh. So another responsibility came on to my Dadi. Now she had to visit Poona to participate in the initial ceremonies there\; at this time, my father was almost two years old.

The Sangh preparations started. Family, friends and community members were informed about the forthcoming opportunity to travel around the Indian subcontinent, with the cost to be borne by the Sangh's organisers. This was a big event for all the people who were eligible to travel in this Sangh. Most people during this time had not travelled more than 20 miles beyond their homes, and here was an opportunity to travel around the Indian subcontinent for more than two months with a nominal sum of Rs. 27 as travel expense to hold a seat in the sojourn.

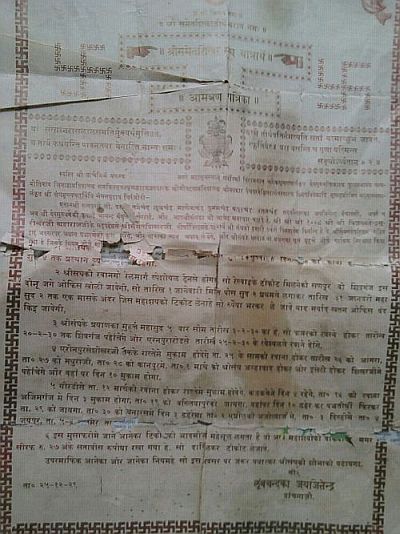

The Aamantran Patrika (Invitation Document) sent in December 1929 to invitees for the 1930 Sangh

There was heavy demand to participate in this Sangh. In the end, the Sangh needed five coordinated trains to transport almost 4,000 people. Vanaji had amassed a fortune, but even he did not realize the toll this would take on his family's savings. He had set out to perform this task - and he would complete it, regardless of the cost. The financial effects of the Great Depression that started with the American Stock Market crash of late 1929 did affect Indians, but would not be evident to Vanaji until after the conclusion of the Sangh. All his family and friends admired him for the amazing adventure he was planning, and he was becoming an icon in the Jain community.

Saklibai, with a two year old toddler, being the Grand hostess for this endeavour, had to still be the lead in organizing travel for all the family and extended family members, including married sisters in law, daughters, nieces and their in-laws and family members. My Bhua had gotten married by the time the Sangh commenced this trans-India trip. The entire Katariya household, relatives and extended family (Katariya was Vanaji's surname, Sanghvi is the title formally applied after the Sangh, and then used as a family name) participated in the Sangh. So, their homes and businesses in Pune, Sirohi, and elsewhere were closed for the entire time of the Sangh's itinerary from February 1930.

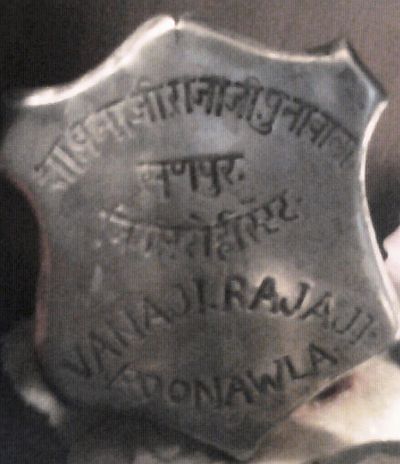

The Identification badge for the travellers on the Sangh

A unique feature of this Sangh was the absence of a lead Jain Acharya or Guru-Lead Teacher. The strictest Acharyas and Munis or Monks - adherents of Jain Spiritual practices - do not use any mechanical or electrical equipment, and travel everywhere by foot. So, there was an absence of a Spiritual lead in the Sangh's entirety. However, there were religious discourses at the beginning and at various Jain centres and Tirth stops enroute.

The Sangh had a major mishap before it ended. The community members have always speculated about its cause, and some have attributed it to the absence of a lead Acharya.

The Sangh reached Shikharji or Parasnath Hill (in present day Jharkhand state) after about three weeks of travel via present day Rajasthan, Agra, Mathura, Kanpur, and Allahabad. At Shikarji, there was a ten-day stop.

This mountain has twenty or more peaks\; it is the most important Jain pilgrimage centre. All the travellers in the Sangh had enough time to perform the minimum 27 kilometre (there are other paths which are longer, and as large as a 54 kilometre pathway) pilgrimage by foot up the 1.35 kilometre mountain. There was also planned celebrations on March 2, 1930, picked as an auspicious day and time to dedicate the “Sanghvi” title to Manikchand and Saklibai, Lumbaji, Vanaji and all members of the immediate family.

The map here indicates the 2,500-mile stretch of the Sangh in 1930, on a present day map of India.

A few of the key towns on the Itinerary are shown

A.

Sanpur/Abu Road.

B.

Agra/Mathura

C.

Parasnath Hill/Shikharji

D.

Kolkata, erstwhile Calcutta.

E.

Azimganj.

F.

Bakhtiyarpur.

The later part of the itinerary skirted through Bengal (including present day Bangladesh) with stays in Azimganj and Calcutta for several days. The next stop on the itinerary was the ill-fated 10-day visit at Bakhtiyarpur.

At that time, this town had a Jain community and a railway station. It was also conveniently located to coordinate several trips to historical sites in the vicinity Kundalpur (birthplace of the 24th Jain Tirthankar Mahavir), Nalanda, Rajgir and Pavapuri (where Mahavir attained Nirvana).

The Jain community here was excited to receive this historical Sangh. They had organised a Navkarsi or Luncheon organized in the town for all people. Unfortunately, a Cholera epidemic had arisen here. In their enthusiasm, the locals had failed to disclose this to the organisers. In a couple of days, several people started showing mild to severe symptoms of the disease.

Sadly, Manikchand, my grandfather who was in his early forties, was one of the victims of this infection. After severe dehydration and shock, he and almost 200 people died in the next several days. The Sangh that had been already in motion for almost eight weeks was getting out of control in terms of sickness and the epidemic of cholera.

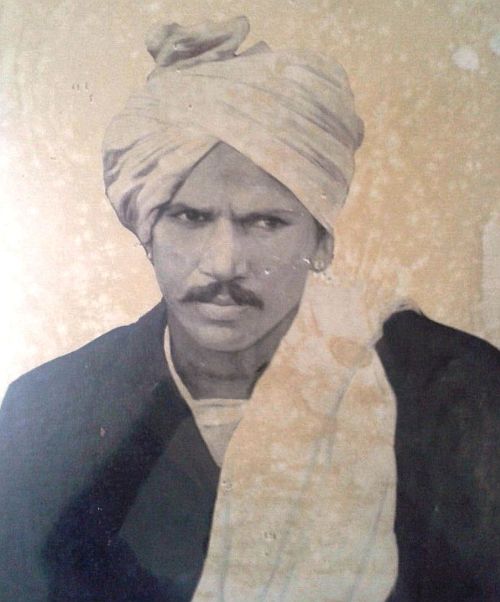

Manikchand, my grandfather 1929

Saklibai lost her husband in this Sangh and became a widow. After the death and funeral, the family hurriedly had a dedication ceremony in memory of Manikchand at Bakhtiyarpur, and after the Sangh reached back to Abu Road for the official culmination of this historical trip.

Saklibai’s life at the young age of forty changed even more after the death of her husband. Per the tradition of the time, Saklibai, a bejewelled lady of the house, had to discard all her colourful clothes and jewellery, and switch into the garb of a widow. Less than three years later, her only daughter, my Bhua Dharmibai, became a widow when her husband succumbed to an undiagnosed perforated appendicitis. She had already had a miscarriage before, and was pregnant during the time. The shock and suffering of widowhood lead her to lose her unborn child once again. After this, Saklibai had to take care of her daughter once again. According to the customs of that time, the twenty one year old widow could not remarry within the society.

The stress of losing her husband and other family members, and the care and responsibility of a large family was taking a toll on Saklibai’s health. On the advice of a local Vaidya in Sanpur, she started using an oral opiate to help her cope. Over time, this led to her dependency on the substance. Thus, in post independent India, where all raw drugs are controlled, she was a legal recipient of the required dosage until her death.

Saklibai had her first grandson, Javerchand, born to Punamchand and his wife Tipubai just after the Sangh. This was Punamchand’s only child who survived to young adulthood. Ratanchand (my dad) and his nephew Javerchand went to the same School in Poona and were close. Unfortunately, Javerchand succumbed to typhoid at the young age of fifteen, a terrible loss to my Baasa and Aunt, and another blow to Saklibai.

By 1948, just after India’s independence, almost all the women were mostly living in Poona with frequent visits to Sanpur. Saklibai also had her widowed sister-in-law, Sadibai living nearby with her family in Poona.

Saklibai enjoyed peace and contentment after 1950, after my parents started their family. She enjoyed spending time with her grandchildren, telling them stories and taking care of them. Of course, she was a primary support for Dharmibai, her widowed daughter. Over the years, Dharmibai had several health issues including a bout with early-diagnosed Breast cancer and a Mastectomy at the Indian Army Southern Command Military Hospital, in Poona. Saklibai along with my mother, Diwali, were her primary care givers.

My Grandmother suffered from chronic asthma. Late into her 70s, she also suffered from moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Since this disease is progressive, in the last several years of her life, she would experience dementia symptoms. When she had her moments of lapse, I remember her trying to recognize the present faces around her with the past time frame that she was experiencing.

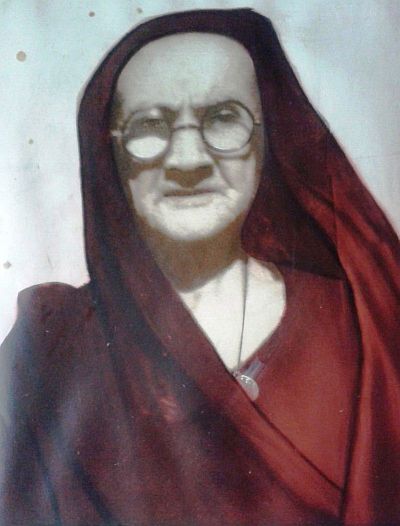

Saklibai, my grandmother, 1970

After a brief illness, Saklibai passed away on September 7, 1980, with most of her family, including her three children, seven grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren around her. Saklibai passed away on the first day of Paryushan that year, which is considered one of the most auspicious days for the Jain community.

Author's note: This is my attempt to document the life of my Paternal Grandmother Mrs. Saklibai Sanghvi, born 125 years ago. I have rigorously researched events that happened during the time and used my childhood memories, having heard anecdotal stories of events that happened during and in Saklibai's life. If I have inadvertently, omitted or modified any occasions in the write up, I ask for the readers' forgiveness in advance.

© Jitendra Sanghvi 2014

Editor's note on comment box: All comments written by real people are approved. The purpose of the approval process is to stop rogue software robots from placing unwanted advertisements.

Comments

Add new comment