Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Chapter 11 Family life

Category:

Tags:

Visalam Balasubramanian was born in Pollachi, on May 17, 1925. She was the second of three children. Having lost her mother at about age 2, she grew up with her siblings, cared for by her father who lived out his life as a widower in Erode. She was married in 1939. Her adult life revolved entirely around her husband and four children. She was a gifted vocalist in the Carnatic tradition, and very well read. Visalam passed away on February 20, 2005.

Editor's note: This is Part 11 of her memoirs, which have been edited for this website. Kamakshi Balasubramanian, her daughter, has added some parenthetical explanatory notes in italics.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9 Part 10

My children and I came to Jabalpur early in June 1949 when the monsoon rains begin. For the first month or two we did not have a good house. The one TVB (her husband) had taken up was spacious but the landlord was a NASTY man who gave us no end of trouble. We were inexperienced and let him bully us. He even cheated TVB out of a few hundred rupees.

One very great, unforgettable friendship was developed there. We came to know Sri. R. C. Ramakrishnan, who happened to be TVB's colleague at work. He was a simple man, coming from a very ordinary family. He belonged to Coimbatore town. He was so fond of my children that he spent almost all his free time in our house. As I was an indifferent cook and possibly worse as a manager, TVB and he arranged that he eat his dinner with us, getting food from the hotel where he was having his other meals as well.

Savithri was very puny and delicate at that time. It may be said that what is destined happens - do what you will. But, all the same, if I had had some sense I could have definitely prevented some of the illnesses that she bore. I have felt bad about my folly and lapse but there is nothing that I could do now.

She wore warm sweater, socks and shoes. But her knees were exposed and she got an attack of (arthritic-rheumatic) pain. Then she had enlarged tonsils. The long-drawn oil bath of those days made it worse. Jabalpur itself was place known for its unhygienic surroundings. So every time she came down with a fever, which was often, RCR (RCR stands for R. C. Ramakrishnan. We children called him RC mama-KB), used to sit with her patiently. TVB was short tempered and would scold people for falling sick. (That nature still continues). RCR played with all the three children but he was extremely fond of Papu, who was about 8 or 9 months old. He used to hold her aloft and call out all the baby names he had for her.

One of the major illnesses that Savithri contracted there was typhoid. TVB had come to know a Bengali gentleman in his office who was a practicing homoeopath. And for some time TVB used homoeo remedies for all of us. In fact, even when it was not the done thing. Homoeopathy doesn't claim preventive action nor any kind of prophylactic treatment. But that Mr. Sen said that as I was prone to getting arthritis, he would give me something to make me resistant.

Mr. Sen treated Savithri during her typhoid. I don't know what prompted me. It must have been the natural concern of a mother for her child. I undertook to recite Sri Mahavishnu Sahasranamam (a Sanskrit devotional text) every evening till she was all right, sitting on her cot/bed by her and holding her wrist in my right hand. I know I had complete faith. Strangely enough, I never even bargained with God which I might have ordinarily done. She was a small girl with very expressive eyes and a very pretty face. She was the most beautiful of our children. She must have been happy that I was doing something especially for her or perhaps she too was touched by the same faith. She would lie absolutely quiet, looking at me steadily throughout my recitation.

Sri. RCR was living alone in Jabalpur then. He too had got posted to Jabalpur along with TVB. So, it was equally new to him as it was to us. His family was to join him a little later. His wife had delivered her second child, and his mother and she were to come together.

His mother was an orthodox person. She would not (could not) eat anything (i.e., cooked food) during a journey, however long it may last. They arrived by a night train reaching home by 9 or 10 p.m. having travelled from the previous day morning from Madras. With my expert knowledge, using my skill, I had cooked dinner for all of them and taken it to the house that RCR had by then taken up on rent. Since TVB was going to the station to receive them, I too went along with the children. Alighting from the train, paati (Tamil for "grandmother"--KB) was so fatigued with hunger she couldn't speak. I must have given a hand helping her to alight. I don't remember doing it. We had kept hot water ready for them to bathe on arrival. The dinner must have been welcome, owing to their tired condition because they enjoyed it. RCR's wife Meenamba was also an extremely nice, friendly person.

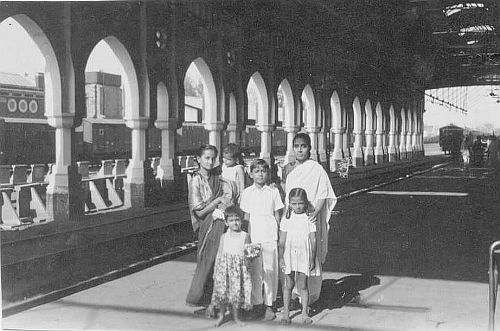

L to R: Visalam with Radha on hip, Papu in long dress, Ramani and his sister (RCR and Meenamba's children), Meenamba. Jabalpur Railway Station 1952. Departure of TVB family for Madras.

This is a farewell photo at the train station in Jabalpur. TVB and Visalam were leaving on transfer for Madras. 1952.

It seems when RCR met them at Itarsi, where they change trains to Jabalpur coming from Madras, his mother observed that he must have been lonely, and missed his family and children. And RCR replied, "That is what you think! I have actually gained three children." "How three children in a span of a few months?" asked his mother. "Come and see for yourself. I have even got a son and daughter-in-law for you--a plus!"

And she always said to me, "The moment you helped me get out leaning on your arm, I took you into my heart as another daughter-in-law."

We had other good friends there. We used to go picnicking in groups to scenic places along river Narmada. There was a place of pure white rocks through which Narmada flowed. In one place the rocks on both sides came so near to each other that a monkey could jump across. A little above, the river flows down in a waterfall and in this narrow passage the river runs very deep. Here, the current is swift, and water whirling because of the submerged jutting rocks. Mechanized and rowing boats ply up to a point against the current there, taking sightseers.

The boats rock madly in the gorges. As it is a famous and beautiful place - especially in full moonlight - lots and lots of boats could be seen during the months when the weather is nice. There would be swimmers also. Friendly competitions as to whose boat would go faster or nearest to the waterfall would also catch the fancy of the other picnickers. The whole place would be full of shouts, laughter, and nervous giggles of women. There were other sandy places on the banks, well suited for playing games as well as eating.

TVB used to go to the club to play Bridge and he also took part in cricket tournaments. Entertainment like cultural programmes, film shows and an annual All India sports events for the Posts and Telegraph staff employees were held regularly. There were several branches of the P&\;T (Posts and Telegraph) offices situated in Jabalpur. TVB was working in the Training Centre as one of the teaching staff. There were new entrants to the department. Having graduated from either engineering colleges or degree colleges, they were in Jabalpur after coming out successfully in competitive exams.

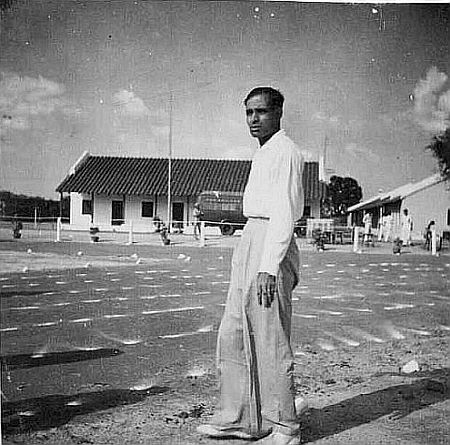

TVB enjoyed sports and played cricket. Jabalpur c. 1952

There were others, older hands, taking up departmental exams and doing short courses. Whatever their age, the ones who had the nomenclature of 'student' held the teaching staff in an elevated, reverential position. During the time we were there, it was a close-knit sort of community. Celebrating national days, all the festivals together, they managed to create a very friendly atmosphere.

Soon after we moved to Jabalpur, Ramesh developed fever one morning. Sudden, slight fever was a common thing, and I did not worry much. I detected his fever somewhere around 9 a.m. He was a little over 2, Savithri was 5, and Papu about 8 months. An old man, who took the children out for a stroll both morning and evening had gone home, as usual, by 10 a.m. or thereabouts. Around noon Ramesh's temperature was shooting up and I began putting a cold pack on his forehead.

By 1 p.m. he started to talk as if in delirium. Wanted to be moved from one room to another, from one bed to another. I thought maybe he did not like a certain room for its size or a bed for its comfort, or something. Even though he talked clearly, his eyes weren't all that steady and he began asking for 'his' mother. That alarmed me. When I said I was his mother and was there near him he said repeatedly, "Not you. I want to go to my mother."

I had to get TVB quickly. Oh God. There were no neighbours at that time. So, I couldn't ask somebody to run across and fetch TVB.

Then I decided I will walk as fast as I could carrying Papu (his office was within half a mile\; possibly 3 or 4 furlongs) and most of the route could be seen from our house. Taking Savithri along would delay me. Leaving Ramesh all alone was risky. Naturally Savithri was scared of being by herself, bolting the door (it was only a bamboo trellis) from the inside, with her sick brother. I persuaded her to keep seeing me as I ran across.

She agreed. But, when I had gone a short distance she cried loudly and I had to return. Every minute without getting a doctor seemed frightening to me. But I had to pacify this young girl, too. She was too young to remain in a house, without any neighbour in the adjoining houses.

The second time I convinced her, told her to keep an eye on her brother and I went. As TVB's office was inside a 'protected' area, this being part of a gun foundry, the gate keeper tried to prevent me from entering. But, my determination and speed were such that by the time he was into the middle of his sentence, I was already nearing the room where the head of the training centre was. Luckily he was sitting there, and not away in one of the class rooms.

I told him briefly how ill Ramesh was. He sent for TVB immediately and asked him to proceed home at once. This gentleman was N.V. Shenoy. He wouldn't hear of my walking back home and drove me back in his car.

A doctor was brought within minutes. That there were so many men and doctors to turn to was reassuring. But Ramesh's fever defied diagnosis as well as treatment. His fever raged for nearly two days. All the while he did not recognise us and was talking nonsense.

Suddenly, in a flash it occurred to TVB that Ramesh might have taken fright from seeing a drama in which a man dressed up as a ghost was chatting to Ramesh, even picking him up, in the green room before the show began. There was a Purohit (Satrigal in Tamil) who was a healer, and he could chant incantations to treat poisonous bites, skin rashes, and fevers. TVB got him and by the first recitation of his mantra, Ramesh's fever came down and his face cleared up.

We have had more than one such scary time with Ramesh falling ill. Indeed, there have been absolutely terrifying times with the other children, too.

Looking back, I think, both TVB and I never, ever admitted - even let ourselves admit -fear or failure. By shutting our mouths tight, gritting our teeth, and putting our strength together, we always held out against any possible doubt. At such times, we never talked much and what little we said to each other was how soon and how surely we were going to beat the illness. The looks we exchanged were always like a joint challenge by both of us and it was always as if one was asking the other, "Are you just as strong as me?" and counting on our mutual support to drive that illness away.

Ramesh developed jaundice while in Jabalpur. My children have always been very obedient, understanding and cooperative, even when they have been sick. Giving them medicines, putting them on a strict diet, or altering their routine for a while has never been a problem. Although he was a child, keeping Ramesh on a fat-free diet and giving him juice of raw radish or the water it had been boiled in was possible.

When he was ten and we were in Delhi, he suffered from a severe attack of dysentery. His condition became really bad. The doctor in Safdarjung hospital told TVB that there was not much that could be done by way of treatment and by putting Ramesh in hospital they could keep him comfortable and that was all they could do. TVB might have admitted him there, but the regulations there allowed only one adult to remain with the child. TVB thought (he told me so) that with only one of us with him and should something happen.. It was simply unthinkable, and he decided against even the so-called comforts the child may get there. Sri. TKB (T. K. Balasubramanian, father's youngest sister, Kalpagam's husband--KB) was there when TVB brought Ramesh home, and conveyed all this. He had come to visit Ramesh on his way home from his office.

We decided we would just sit with him through the night. I prayed, i.e., made a vow that I will recite Sri Lalitha Sahasranamam (a devotional text in Sanskrit--KB) on all of the nine days of the ensuing Navarathri and devi (goddess--KB) will spare me Ramesh and enable me to fulfil my vow.

I still think it was nice of TKB to come and spend the night with us. By God's grace, Ramesh's condition did not worsen (neither did it improve) but remained about the same during the night. Early next morning, a barber who used to come to cut TVB's and Ramesh's hair turned up. TVB told him of Ramesh's condition. He said he knew a homoeopath whom we should bring home to see Ramesh, and give medicines. Accordingly, TVB brought the doctor within minutes, with the barber also accompanying them.

Here I must say there are people who talk slowly, but that doctor was slowness personified. He took out a number of phials of powder, cut out square pieces of white paper, began marking the bits of paper as '1', '2' and arranged them in a row. Then he took a large sheet of paper and began mixing some of the powders together. All the while I was nearly pouncing on the packets that he was folding.

After he completed the process of folding and marking, he directed that I give Ramesh the one marked '4' first. He said he will wait and watch the progress. And he did. He sat for more than half an hour. Within say 20 to 30 minutes of administering that No. 4 powder, Ramesh asked for water, which was what the doctor had told us beforehand to expect as an indication that the child will pick up from then onwards. Along with water, we were to give him powder No. 6. After that, there was no fear, and we were to continue with the rest of the packets of powder as per prescribed schedule.

A few days later we had Navarathri. Kalpagam's son Samu was in our house with typhoid. He was a boy who never gave any trouble. Looking after him during his fever wasn't a problem for my reciting Lalitha Sahasranamam. We also had a boy, Mahalingam, to help around then. But, as if to test my endurance and stamina, Kalpagam had a miscarriage and she came to our place from the hospital for recuperation. She was very understanding. Even while cooking for her husband and children and looking after her and Samu, I was able to recite the Sahasranamam as I had intended. She, her husband, and children never intruded or inconvenienced me in my routine.

____________________________________________________

© Kamakshi Balasubramanian 2016

Editor's note: I approve all comments written by people\; the comments must be related to the story. The purpose of the approval process is to prevent unwanted comments, inserted by software robots, which have nothing to do with the story.

Add new comment