Latest Contributions

Remembering (?) the Day India Became Free

Category:

Tags:

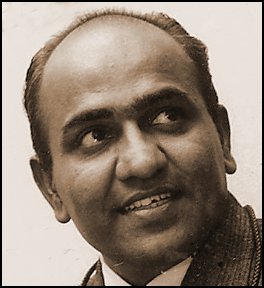

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

Chikkanayakanahalli is a small town about 130 km from Bangalore. I still remember vividly that a group of people – volunteers for the Independence movement – stopped my friends and me as we were walking to our school. They snatched the felt hat I was wearing and threw it on a bonfire of clothes. As the rising flames swallowed my hat, I felt a sense of shock at losing my precious possession and walked back home, crying all the way. It was the Quit India year, 1942.

On the day India became independent, I was a schoolboy in a small town called Doddaballapur in Karnataka. My father was the doctor in charge of the government hospital there. We lived in a small ‘out house’, a two-room block, behind a local jeweller’s mansion. My mother and the rest of the family were in Mysore, about 180 km away.

When he was transferred from Mysore to Doddaballapur, my father chose to take only me along with him, and left the rest of the family in Mysore to avoid disrupting the schooling of his children. I had just finished my Lower Secondary examination (7th Standard) and was waiting to join a high school. If I moved out with my father, I needed only to join the high school at Doddaballapur. Added to this, possibly, my proven interest in housekeeping and cooking also contributed to my selection.

In Doddaballapur, my father arranged with a local 'mess' run by a Palaghat Iyer for our meals. He was an old man with a flowing beard who looked like the Rishi in a Ravi Verma painting reproduced on a calendar we had at home. Every day, a young man from the ‘mess’ brought us our food, hot and delicious, in a shining brass food carrier.

My best friend was a boy of my own age who worked as a servant in the jeweller's home. We went to the same school: the Government High School. His name was Rudramuni, Rudra for short. In addition to his studies, Rudra had to help the jeweller's wife in the household chores. Since he was not very good at his studies, I helped him often to finish his school homework.

Even after 60 long years, I am able to recall in detail those early years of my life. But, I remember very little of what happened in our town on the day India became independent. One possible reason is that the significance of this historical event was felt less in the small towns of South India. Another possible reason is that perhaps not much happened, at least where I lived. We had no radio at home. Only an English newspaper arrived every morning, which, after my father finished reading it, was collected by Rudra for the jeweller to read. It was rarely returned.

Independence Day 1947 was a holiday. We went to the school without our books in the morning to take part in the flag-hoisting ceremony. More than the significance of the day, the holiday from school meant much more to Rudra and me. At school, we were given little flags, which we pinned proudly on our shirts. In addition, volunteers gave us each a white ‘Gandhi cap’ to wear.

My father went to work and came back from the dispensary as usual, and did not talk about the big day. But, the extra sweet dish in one of the compartments of the brass carrier that arrived from the Iyer mess made all the difference!

Nevertheless, Gandhi, Nehru and Patel were names with which I was very familiar. They were the names I heard whenever the Congress party organised street processions. I made it a point to join such processions, and walk with the slogan-shouting men and women. This gave me a special thrill, although I knew very little about what the slogans meant except that either they were against the British or in praise of our leaders.

In contrast, the day Gandhiji was assassinated in 1948 remains etched in my mind. I was taking part in an RSS drill in the maidan (open field) when the news came that Gandhiji was dead, shot by an assassin. The local RSS leader, a young man in his twenties, who was conducting the evening programme announced the sad news and urged us to go home. My father was already back from his evening walk. I saw him engaged in a serious discussion with the jeweller. The jeweller’s older son, who used take part in all local Congress programmes in the town, was crying. I did not cry but I think I experienced a strange loss. After all, Gandhiji was so dear to all of us. I heard groups of people running on the street urging shopkeepers to close. Strangely, the meal carrier from the ‘mess’ did not arrive. My father too did not utter a word.

Epilogue. On August 15, 1947, huge crowds rejoiced on the streets of Delhi. Comparatively, for most of us in the small towns and villages of South India, the day was largely quiet and the celebrations simple. Perhaps, we were too far away from Delhi to hear the drum beats of freedom. Was it because the battlefields and all the gunfire of the movement for freedom were largely in the North, and the South felt only its tremors?

© T.S. Nagarajan 2007

Add new comment