Memories of the 1940s

Category:

Sadhona Debi Chatterji, seen here with Aadhira, one of her great-grandchildren, was born in October 1931 in Calcutta, to Hari Prasad and Subarna Bannerjee. She did her matriculation, and got married to Birendra Kumar Chatterji in June 1948. She has a son and a daughter. Her husband, like her father, was in the Imperial Bank of India, which later became the State Bank of India. Her husband retired as Chairman UCO Bank in 1984, and passed away in 1989.

She has had a tremendous interest in national and world affairs, with her own opinions on many issues. She is an avid reader. She has been a popular and well-loved person among the family and a very large circle of friends. Even at the age of 85 and ailing, she gets phone calls from all over the world.

Calcutta (now Kolkata), February 1942.

It was one of the worst times in the history of undivided West Bengal before Partition (1947). The Second World War was going on, and the Bengal was suffering from the great Bengal famine. There was nothing to eat, and thousands of poor people were dying of hunger. Hundreds and hundreds of them were coming to Calcutta from the villages in search of food. I have seen entire families on Calcutta streets, begging even for a whiff of starch, which people throw away after cooking the rice. It was so very upsetting for me. Life was so different in Lyallpur (where my father was posted at that time) from all this. By God's blessings, we did not know what poverty or hunger was.

Those old days - it is very difficult for me to forget easily. Even after sixty years, I can still see those people suffering from poverty and hunger, trying somehow to survive in this cruel world, in the horrible heat. Those skeletons in human form walking on the streets of my very, very dear Calcutta, begging for just a bowl of rice starch to eat or a piece of cloth to cover their bodies. It was heart breaking. I was only eleven years old, but even at that young age, all those sights made me very unhappy. How could God be so unkind, he who is the source of love and kindness? The father of all humankind?

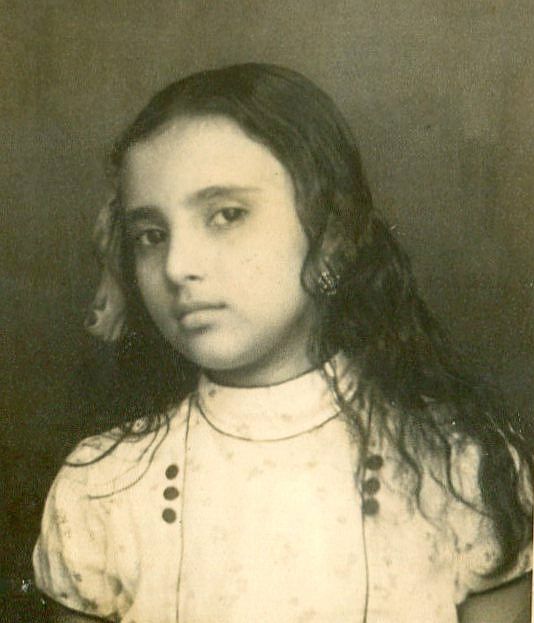

Sadhona Bannerjee. Early 1940s.

This was the time, when Labumashi's (my mother's second sister) marriage was fixed in Calcutta, and my parents decided to attend the wedding.

My family (my parents, my two sisters, my brother and I - Jhunumoni, my youngest sister was not born at that time) used to live in Lyallpur in Punjab, far away from Calcutta.

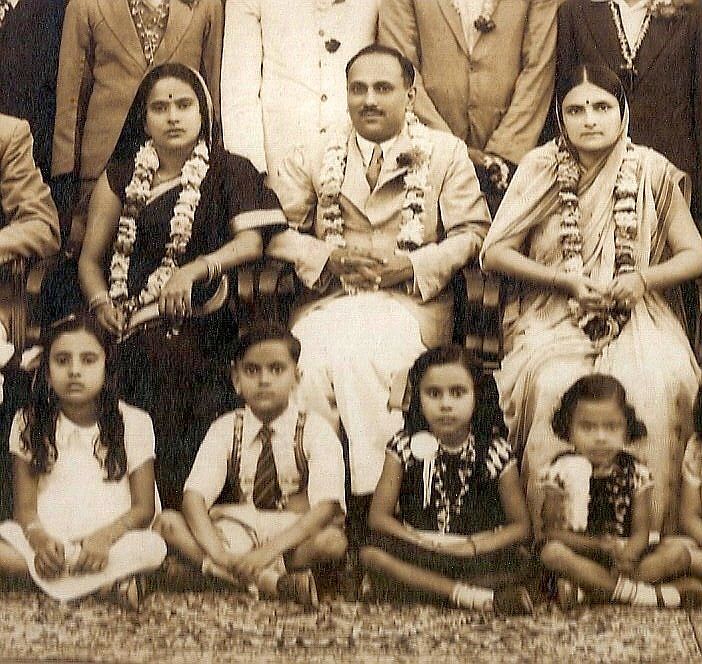

Sitting on the ground: L to R: Sadhona (author), bhaiya (Ashish, brother)), Bunu (Sumana, sister) and Chotu (Suparna, sister)

Sitting on chairs: L to R: Subarna Bannerjee (Sadhona's mother), Hari Prasad Bannerjee (Sadhona's father called Babun), and unknown. Early 1940s.

Life was very peaceful there, without any problems for our family. It was an easy and happy life, and we had very little idea of what was happening in Bengal. At least, we children knew nothing about it.

We left for Calcutta with Ma to attend the wedding. Babun, my father, joined us later. The long journey from Lyallpur to Howrah, almost across the country, took four days. While in Lyallpur, we had to make this journey three or four times. We children used to enjoy it very much. We had to leave Lyallpur in the evening by train, which reached Lahore the next morning. From there we had to catch the Punjab Mail for Howrah, which we reached after three days.

We left home in Lyallpur in our big Chevrolet car driven by our driver, Daniel, wearing his khaki uniform with shining brass and his smart driver's cap. The station was not very far from our house, and the train left on time. Next morning, before we reached Lahore and got down at Lahore station, Ma made the four of us wash and brush our teeth and get ready.

I remember my Ma, how efficient and smart she was. She was married at the age of twelve, and had studied up to class V/VI in Lady Irwin School in Simla. So she never had a chance of getting a proper education. But I remember very well that it never made any difference in her life. She was a very intelligent woman with a lot of self-confidence.

Subarna Bannerjee, Sadhona's mother. 1940s.

We used to travel a lot in our younger days. Because our Babun used to be very busy with his work in the Imperial Bank of India and could very seldom join us in our travels, we had to travel with Ma only.

My father was a Senior Staff Officer in Imperial Bank of India. In those British days, it was thought of as a very prestigious post for an Indian. Most of my father's colleagues in the bank were either Scotsmen or Englishmen.

I still remember even now how efficiently Ma travelled with four children without Babun. The guards and the ticket checkers of the railways were mostly Anglo Indians, and very often they used to harass Indian ladies if they found them travelling without men. But my Ma, with her broken English and her strong personality, used to tackle them very well.

The railway compartments used to be very different then. When we were young, there were no air-conditioned coaches: only first class, second class, inter class and third class. Each compartment was separate. For first class coaches, there used to be an additional attendant's coach, with a connecting door with the main compartment.

Whenever we travelled, both our servants used to travel with us: Madan Singh, our cook, and Sattarma, our maid. Travelling used to be lot of fun with the entire family and the servants. My bhaiya (brother) used to spend most of the time in the attendant's couch, playing and chatting with Madan Singh.

At Lahore station, the next morning, when we got down from the Lyallpur train, we went to the refreshment room, which was run by Keventer &\; Company, the official caterers of the Railways all over India. We had our breakfast of eggs, toast and milk.

Latter, sometime during the day, we left for Howrah by Punjab Mail. As I have mentioned before, it was a long journey. The four of us children, Bunu, Chotu, Bhaiya and me, enjoyed it thoroughly.

L to R: Bunu (Sumana), Sadhona, bhaiya (Ashish Bannerjee) and Chotu (Suparna). Early 1940s.

Throughout the journey, Ma got food for us from the dining car in the train. For lunch, chicken curry and rice, and for dinner, egg curry and roti. Ma always used to carry lots of fruits and biscuits, and the delicious cake she used to bake at home. Another thing that always used to be there was a bottle of Horlicks. Ma used to get the hot water from the dining car, and instead of tea, we, the children, were given a cup of Horlicks, while travelling.

During the journey, I used to be the storyteller. I used to make up stories, as we passed through the countryside, and my three younger siblings would listen to me with great attention. Bunu and Chotu would lose interest very soon, but Bhaiya used to listen with great interest most of the time.

At Howrah station, we saw our very, very dear old Dadu (mother's father), Shree Ashutosh Chatterjee, waiting for us with a big smile on his face. He was a wonderful man. He passed away when I was 19 years old. I have rarely come across a better and a more loving person than him in my life. He came from East Bengal, from a place called Ichchapur.

Sadhona's maternal family. 1940s.

Second row: Extreme left: Sadhona\; Fourth from left: Subarna Bannerjee, Sadhona's mother\;

fifth from left: Sadhona's grandmother\; Extreme right: Dadu (Sadhona's grandfather).

His father had three wives, and my Dadu was the second one's son. His mother passed away when he was only a few months old. After that, his Nani (grandmother) came and took him away to her house in Bali, near Dakhineshor, and brought him up with her own two sons, who were more or less my Dadu's age at that time. He grew up in his Mamar Bari (home of maternal uncle) with the Gangulis of Bali.

My Dadu had his own house in Calcutta, P 195 Raja Basanta Roy Road. It was a big three storied house, built only about three years before he retired from service. He retired as Superintendent in the Finance Ministry in Delhi, and had his office in North Block.

When we went to visit my Dadu and Didima (grandmother) in Delhi in the 1930s and 1940s, we lived at 27, Gurdwara Road, his official residence. It was a nice bungalow, with three bedrooms, a big drawing room and a dining room. It had a nice garden also with a front and back lawn, servant's quarter and a garage. The house used be full of Mentu Mama's (mother's brother) friends from St. Stephen's College most of the time. Bharat Ram and Charat Ram, and two three others, were almost daily visitors. I do not remember all the names now, but one of them later in life had become a general in the British army. Every evening, when his Nepali driver took his big black Chevrolet car to bring back Dadu from his office, I used to go in the car.

My Didima, Anupama, was a sweet friendly person. She was short, very fair and fat. She came from a rich zamindar's Mukherjee family in Bengal. Her father was the second of seven brothers. When Edward VII, the Prince of England, came to India in 1875, he was invited by the Mukherjees at their estate, and the seven wives of the seven brothers had welcomed him by doing baran (welcoming guests with agarbatti, flowers, etc. on a thali, and moving the thali in a clockwise movement three times). Each of them carried a golden ghada (pot) with water in it. The Mukherjee family later got the title of Raja. My Didima came from this Mainapurer Rajbari.

She was very fond of people, and loved feeding them. Hers was an open house for everyone, all the time. Her dining table was always full of good and tasty food. Bunu, my second sister, has inherited this habit from her.

My Dadu was very dear to me. I was very fond of him, and he was very fond of me, his eldest grandchild. He was tall and dark, with a very good personality. Even now when I close my eyes, I can see my Dadu's tall figure in his gray trousers, black knee length bandhgala coat and black round topi on his head, coming down the North Block steps - that wonderful man, my Dadu.

When we reached Basanta Roy Road, we found the entire house was covered by while cloth from outside. Dadu told us that because of the ongoing war, Calcutta was under "black out", and no light should be seen from outside after dark. The streetlights were very dim, and those also used to be switched off during any air raid by the Japanese. But fortunately, during Labumashi's wedding, there was no air raid in Calcutta.

Next day, Mejomamima (my mother's third brother), Arumashi, (my mother's youngest sister), Budumama (my mother's cousin brother) with little Joy with them, came to Calcutta from Delhi. Joy was the first grandchild from Dadu's son's side and everyone was very happy to see the baby. Joy was, I think, only three months old at the time of the wedding.

That evening, we went to Lake Road, to meet the groom's family. Their's was a big joint family. The old grandfather and his two sons with their families used to live in the same house. They were a middle class family with rice fields in Jalpaiguri and some tea gardens also.

Shambhu mesho, Labumashi's future husband, was a nice, simple person. Not very well educated. He had some sort of a diploma from some place in Jalpaiguri. The University had not come up then. He worked for Jessop Company in Dum Dum, from where he retired as a Senior Foreman. Years later, when I got married, he became a good friend of my husband.

Labumashi was a pretty girl. Fair with lovely curly hair. She had her schooling in Delhi from Lady Irwin School. She was a good dancer, and used to participate in many of the school functions. Once, when she was performing in Tagore's Pujarini in school, Lady Linlithgow, the Viceroy's wife, was the chief guest. She was so impressed by Labumashi's performance and her looks that she requested the Principal to ask the dancer to come down from the stage. She then congratulated Labumashi for her performance, and said, "I wanted to find out if the hair on your head was real or a wig."

Babun and Pandumama (my mother's second brother) came to Calcutta one or two days before the wedding. It went off very well in spite of all the restrictions due to the ongoing war, and was a very happy occasion in my life. I was just a teenager, with all kinds of romantic ideas and dreams. After the Boubhath (ceremony to welcome the bride at the husband's home) was over, we came back to Lyallpur.

Away from the horrors of Calcutta, away from all that pain and suffering and hunger, we returned to our quiet and peaceful life. We children returned to our every day school life, to our two rabbits and their babies, two ducks, a number of hens and their chicks and our very dear Bruno, our golden brown Cocker Spaniel. Ma returned to her daily house work, looking after all of us, In the evening, she would go to the club like the other ladies to knit the socks and mufflers with khaki coloured wool supplied by the government, I think, for the soldiers fighting in the war.

Babun returned to his bank work, his games of tennis in the club, and his favourite news bulletin at night by Subhas Chandra Bose from far away Japan, which used to be broadcast for the Nation.

When we went back to Lyallpur and my dear school, we met the Sister, our class teacher. She asked me about my aunt's wedding and how I have enjoyed it. When I told her about the wedding ceremony, and later about the famine-affected people on the roads, without any food and almost without any cloths, she was upset. She said, "Do not be sad my child, pray for them, and ask God to help them. Lord Jesus is there to look after all of us."

I often used to go to the church, which was inside our school compound and sit in front of Jesus. I do not think I ever prayed there, but I remember that only sitting there looking at Jesus, I used to feel very happy. Lord Jesus had a red robe on his shoulder.

Much later, when I was looking for a figure of Jesus with a red robe, someone I did not even know presented me a figure like that. So Jesus came to my house.

In school, I became so attached to the Nuns and their way of living, that I used to tell my mother that when I grow up, I would like to became a Nun and live in a convent.

That wish was never fulfilled, but I have no regrets. Jesus gave me a very, very happy life, a loving husband, two very good children, lots of good friends. The Lord did not leave any thing for me to want in this life.

Sadhona Chatterji. Late 1960s.

I could not have been happier.

______________________________________

© Sadhona Debi Chatterji 2015

Add new comment